Everyone remembers where they were on 9/11 when the Twin Towers fell. If they’re old enough, they remember where they were when John F. Kennedy was assassinated. And Martin Luther King Jr. And Bobby Kennedy. And many of us vividly remember the circumstances in which we read or heard the news in November 1979, that fifty-two Americans had been taken hostage in Tehran by student mobs.

The United States is a big country. Shocking news happens in America—and to Americans—on a regular basis. Like everyone else in the world, Canadians pay attention. But the opposite is untrue, which is one of the reasons why our relationship with the US is asymmetric: No matter what happens in Canada that we may consider cataclysmic (such as, say, a referendum that could split up our country; or a shooting at the National War Memorial), we have no expectation that Americans will have more than a hazy idea about it, if any at all.

My mother was American, so I grew up visiting my Michigan cousins on a regular basis. They came to see us in Toronto, too, but it was clear to me even as a child that while we were expected to be conversant on events of the day in the US, they had permission to be incurious—or, if curious, unapologetically ignorant—about what was going on in Canada. Nobody resented the imbalance.

We understood that what the US did or didn’t do mattered to the world, while what Canada did or didn’t do mattered only to Canadians. We became patient and efficient “explainers” of ourselves to them, and everyone understood that such explanations were a conversational sidebar to the main theme of America.

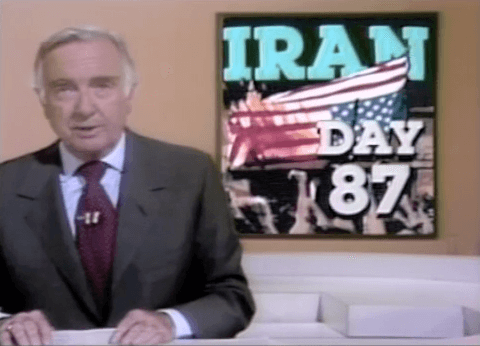

If you’re over forty or so, none of this requires explanation. But if you’re younger, it does. And I am explaining it here because it is the only way I can properly contextualize the thrill we Canadians felt in 1980 when our ambassador, Ken Taylor, emerged front and centre in the Iranian hostage crisis, which would dominate global headlines for more than a year. Taylor’s courage and resourcefulness in managing the cloak-and-dagger “Canadian Caper,” which eventually led to the escape of six American diplomats, brought him fame personally, and an important moment of respect and honour to his country.

Shortly after news of Taylor’s role in the escape broke, our family travelled to Red Bank, New Jersey, to attend the bar mitzvah of one of my cousins’s sons. At one point, the rabbi stopped the services to make a special announcement. “I know that there are many guests here this morning who have come from Canada,” I remember him saying. “I just want to let our Canadian friends know how grateful we are for the actions of Ken Taylor. In fact, I want to now ask all the Canadians in the congregation to please stand up so we can recognize you as the great friends you are and have always been to America.”

Stunned, we rose, and everyone applauded vigorously. I felt like the understudy who has been watching a hit show run for years with the lead performer in perfect health until one day she gets laryngitis, and it’s suddenly my moment to shine. We looked at each other in amazement as we stood, awkward in our attempt to tamp down button-bursting pride with appropriate Canadian humility. We all took ridiculous pleasure in this singular act of recognition. I’m guessing that this little ritual was multiplied many thousands of times across the continent, as Canadians accepted kudos from American friends, relatives and, as in this case, complete strangers.

Ken Taylor died this week, at the age of eighty-one. Much has changed in the three and a half decades since his heroic act. Canada now is a more confident country, with far more claim to global attention. Taylor was, among many other things, a sort of early pioneer in this national transformation. At a time when Canadians were stereotyped as mild-mannered and phlegmatic, he demonstrated the bold moxie of a real-life action hero. And in doing so, he changed the way a country thinks about itself.