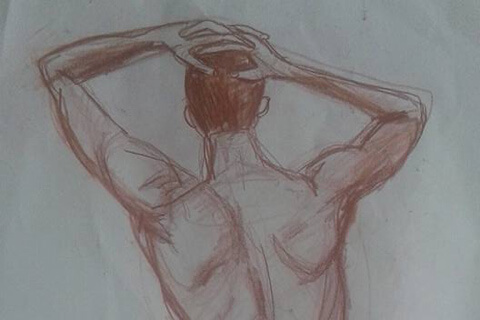

I know the model’s body better than I know my own. He has posed for my class at Central Technical school in Toronto a dozen times this year, so twelve x 2.5 hours a class equals thirty hours of studying that long, lithe, athletic form. Standing, sitting, and lying down. Contorted, writhing, and twisted; climbing, dancing, in a boxer’s stance or yoga asana.

We start off each class with thirty-second poses; barely enough time to make a few quick strokes on rough newsprint. As the morning progresses the poses get longer; a minute allows you to capture not only the main lines of force but also to shadow cross-contour and muscles. Two minutes and you’ll have the ankle, knee, and wristbones; nose and brow. Five, and your sketch is becoming not just any human form but an individual. And ten minutes—oh, ten minutes is an eternity! Ten minutes lets you step back from the easel to observe your drawing as well as its subject; to look critically at what you’ve done and correct it.

The eye is insatiable. To look and look and be utterly absorbed by what one sees is bliss. In fact, my very first memory is of simply looking. Hands are holding a white box in front of me. They open it, and clouds of white paper billow apart to reveal a little smocked dress of purest lavender, overwhelming me with what I don’t have words for yet but will come to know as beauty. When I confided this memory to my parents, they identified it as a visit from out-of-town friends when I was only eighteen months old. But I don’t remember the people. All I remember is the colour.

When I was young I didn’t discriminate between the arts. I got the same kind of pleasure from dancing as I did from making music or painting. I still do, though perhaps not with the same degree of joyful unselfconsciousness, because they all involve a mind–body fusion. The kinaesthetic impulse travels almost without mediation from the brain to the limbs—you hear music and you move; you study the model and your hand gestures his form. There is something tremendously unifying about such experiences. Art puts you back together again. I knew that, and knew that I needed it, so I went to university to study dance and drama, took life-drawing classes, and wrote poetry.

It was only in my twenties that I gave up the dream of pursuing all the arts simultaneously, having been persuaded that to be good enough at anything you couldn’t do everything. The result was that I found myself doing graduate work in English literature.

Perhaps it was because I excelled at writing essays and passing tests that I chose to pursue the only one of the arts that didn’t engage the body as well as the mind. When I brought home good grades my mother was happy—at least for a little while. My mother attempted suicide many times, staging each event at home in the certainty of being found, and saved, by those who would, and did, blame themselves for her misery. And being often accused of contributing to her unhappiness, I undertook to provide the attention she demanded. Until she died two years ago, part of my brain was always tuned to her station. I thought I could keep my mother alive the way a phobic thinks she can keep a Boeing 747 in the air: by concentrating.

Living with a crazy person, it was essential to be able to discriminate nuances; to recount dialogue; to narrate what actually happened as vividly as possible, if only in my own head. And best of all, when I couldn’t bear my world anymore, I could always find safe haven in the worlds other writers had created.

And yet here I am in art school, after a lifetime of taking shelter in literature and having published thirteen books of my own, and I am happy as I rarely was in all those years of reading and writing.

Why?

What killed the comfort of reading and the joy of writing?

The constant erosion of confidence by a grudging community was certainly a factor. Whether as an English professor (rumoured to have got her first teaching contract by sleeping with the chairman, despite the fact that she came first in the departmental exams and won the prize for best dissertation), or a poet (whose editor told her that maternal hormones had destroyed her work), or a novelist (about whom that same poetry editor remarked—when her first novel got good reviews—that she must have lots of relatives who were journalists; whose agent suggested that she write non-fiction instead so they could make more money; and whose publisher said he was too poor to pay her the pittance she was actually owed, though he found the money to pay other people he considered more worthy), I have had my share of indignities. Listing them all would be too mortifying, so let’s just agree that we live in a barbarous age.

This year I took a sabbatical from the writing gig and in drawing and painting, sculpture and print-making have rediscovered happiness. Because making art is not my profession, I have nothing invested in success: no nagging internalized critics, no worries about satisfying the marketplace. The joys of being an amateur are profound, and real, and intensely liberating. This is play, pure and simple.

Nonetheless, I am convinced that this playfulness is not purely and simply because I am a student. It has a great deal to do with the sensuality of the visual arts. You smell the metallic perfume of paint and acidity of turpentine, you hear the squeak of the charcoal or the roar of the furnace, you taste the resinous grit of sawdust and the chalky dryness of plaster, you feel the cool, smooth clay between your fingers, the jolting of the hammer and chisel on bronze. There is so much information to process it takes you right out of yourself into the material world.

Also, instead of sitting at a desk for five years of backaches and migraines sweating out another piece of fiction, you get to stand up and move around and finish painting after painting after painting; sculpture after sculpture. With the visual arts, you can make a lot more stuff a lot more quickly. This appeals to me—I’m not getting any younger, so time is at a premium. And not only do I make more stuff, I get immediate pleasure both from the making and from looking at what I’ve made.

I can’t stress this enough: immediate pleasure. Obviously one’s unitary experience of a work of art is completely different from the cumulative building of responses that is writing and reading. Literature is an art of time; it is necessarily slow. And I respect that; I love reading a poem over and over, turning it in my hand to catch every flicker of light. I love following the multiple threads of narrative to an unforeseen conclusion that makes me gasp and want to reread the whole book again from the beginning. And it is precisely because literature works through time that there are things, amazing things, writing can do that the fine arts cannot, like conveying the phenomenology of human consciousness. Literature brings us intimately into contact with other souls not through symbols but through experience of their minds in action.

In other words, I’m not saying making art is “better” than writing. Only that for me, right now, being at art school is more satisfying than spending five more years trying to write another novel that will take me three years to get published, and that will quietly slink out of the bookstores six months later, never to be heard from again.

There is yet another reason for my satisfaction; one that may be highly individual. As someone who doesn’t have a partner who edits what I write or belong to a writing group, I’ve never had much feedback. Feedback is hard to get when you don’t have a contract for it with family and friends. You can ask, but most people are too busy—or too wary—to help. But at art school feedback is constant and supportive: people really look at your work and try to help you make it better. They say wonderful things like, “That bit is coming forward when it should recede; try greying out the colour more so there is less contrast,” or “The angle of the head is slightly wrong there, do you see? That’s what’s throwing off the model’s profile.” And you look again, and you see what they are saying, and there is this moment of shared vision which is at once inside you and outside you the way the world itself is both inside you and outside you.

Which makes me understand why I felt compelled to talk about my poor angry disappointed mother when exploring my decision to go to art school in my seventh decade, a time when I might have been expected to have already chosen my artistic path and to be content with it. For the me who used to dance, the me who used to draw, the problem was that writing just used my mind; the mind that was the only part of me she respected and the part that strove so hard—and usually failed—to please her. Perhaps the fact that she’s gone now has freed me to go back to my earliest source of joy, that pure colour flooding my vision, the colour that moved me before I even had a name for it, or for the quality it embodied: beauty.

Now I get to look at things insatiably and then make art about them. I am using long-handled brushes that require me to move my whole arm and upper body and I am dancing away from and back to my easel. I am wedging huge clumps of clay and filing and sanding resistant metal. I am etching plates with diamond-tipped tools and slathering them with ink, then removing most of that ink delicately with fine cloth before turning the heavy roller of the lithography press.

I am back in my body and I am never still. And it makes me happy, and it makes me whole.