Fifteen years after Rwandan Hutu massacred hundreds of thousands of their Tutsi countrymen, one survivor and the man who cut off her hand tell the horrible truth about the genocide and explain how, even with so much suffering between them, they eventually made peace.

My name is Alice Mukarurinda. My father was from a village in Ruhengeri, a region in northwestern Rwanda. In 1959, the government forced him to move, with thousands of other Tutsi, to Nyamata, a small, disease-ridden town between a swamp and a forest. My father was forced to move because he was a Tutsi.

For hundreds of years, Hutu and Tutsi shared Rwanda. But being a Tutsi became important in colonial times. When the Belgian colonists came in 1916, they decided the Tutsi were more clever and more beautiful, taller and stronger than the Hutu. Later they introduced policies in Rwanda that turned these two groups into races and divided the country between them.

Jealously grew between the two because Tutsi had cattle, while Hutu worked in the fields. Rwandese society sees people with cattle as rich. So the hatred between the two comes from being greedy.

When the Belgians left and the Hutu took over, Hutu started killing Tutsi. There were massacres in 1959, 1963, 1992, and 1994, but it feels like Hutu have always killed Tutsi. They killed Tutsi because Tutsi have things.

I am Emmanuel Ndayisaba. I am from Nyamata, too. Before the war, I was a metalworker. I never finished school; I was too poor to pay. I would have liked to study English, but why dream about things that can never happen?

As kids, we learned to hate Tutsi from our parents. They said Tutsi are not even from Rwanda. They demonstrated how to kill a Tutsi with a spear. They said we could tell who the Tutsi were because of how they are shaped.

But my mother was a Tutsi, so I was confused. My grandfather taught me all the ways Tutsi are bad; sometimes I interrupted him and said, “But we pray in the same church!” I’d tell him about a Tutsi friend who gave me sweet potatoes or milk. Then he would chase me and beat me with his walking stick.

Alice: In 1989, my brother and I passed the national exam for secondary school. We went to the district office to read a list that matched students to schools, and found our names covered over with a white line. When we went to the director to ask why, he spat in our faces. He told us that the ministry had decided the Tutsi had no right to education. “There is no Tutsi who has any value,” he said.

With that, we knew we had no real future. My brothers decided to run away to the inkotanyi. This was the nickname for the Rwandan Patriotic Front, an army of Tutsi who grew up outside of Rwanda and wanted to return. They were fighting for the rights of all Tutsi.

Government soldiers were stationed along all the main roads in the country; everyone knew that if they caught you on your way to join the inkotanyi, they would tell you to dig your own grave and they would bury you alive. So the recruits would sneak through forests. But two of my brothers were killed anyway. They were fifteen and thirteen years old.

Emmanuel: To me, the starting point of the genocide was March 1992. Hutu put banana leaves above their doors so their homes could be recognized. Even though my mother was Tutsi, we were a Hutu home, and the soldiers came to our house to recruit us to kill Tutsi. I hid, because I had Tutsi friends, but my father and brother went with them. When they returned, they had goats. They told us that they had only chased the Tutsi and found the goats.

Alice: The soldiers started a war of fire, burning our houses and anything next to them. Our father stayed home because he was too old to run away. He was seventy-two years old. They came and killed him, then they took our cows.

After everything that happened, I had to get married. It’s not that I wanted to. Charles Wirabe was almost ten years older than me, and another woman and her family had already rejected his marriage proposal. But because my father was dead and I couldn’t finish school, I didn’t feel I had any choice. I got married in August, four months after my father was killed.

My husband and I tended a small farm. We told ourselves that the war was over, that we had seen the worst. What could be worse than 1992?

Emmanuel: The killings stopped after a few days, but the government continued to mobilize. Local leaders put together a night patrol because, they said, the Tutsi might kill us in the middle of the night. The government also trained a new militia, the interahamwe. They were not soldiers but young men trained to fight with machetes and guns. Some of them even had uniforms.

I didn’t join the interahamwe, even though I was afraid of the Tutsi—not just because of what the government was telling us, but because of what we were hearing on the rpf radio. They broadcast the names of my neighbours, saying that they had blocked Tutsi from getting water at the wells. This was true, but how did they know that? I became convinced there were Tutsi informers among us.

Alice: I saw the interahamwe training in Nyamata. They practised slicing through banana trees with only one cut. “Just as we’ll do to the Tutsi,” I heard them say. Sometimes they came from Kigali in pickup trucks. They didn’t have any weapons, just their drums and their song. They drove around the village singing, “Tubastembatsembe” (“We will kill you all”).

In early April 1994, I was in Kigali visiting family. You could feel the tension. Buses were stopped at roadblocks. ID cards were checked, bags were searched. Local leaders were asking everybody not from Kigali to leave; they even organized buses for us. They wanted us to go back to our villages and join our families. They had lists of every Tutsi family. So I went home.

On the sixth, I heard on the radio that the president’s plane crashed. I thought, “This is it, we’re all dead.”

Emmanuel: There were so many rumours about the crash, I didn’t know what to believe. But I saw many, many Tutsi leaving their houses, pulling their cows and goats behind them. Four days later, the soldiers arrived.

Before I tell the next part, I want to apologize. Until now, we have been talking about soft things. Where I am going will be hard on all of us. I ask forgiveness, and I hope you can be patient and strong.

The soldiers told us to go with them to a house where Tutsi were hiding. A group of us surrounded the house so that no one could escape. I had a machete. One soldier told me, “Kill them so we will be able to take those cows.” I went in. There were fourteen people huddled on the floor, and I killed them. A woman carrying a child on her back ran a little bit, but I caught her and killed her. I even killed a man I knew. His name was Rutase; he was my neighbour.

After this, we took the soldiers’ cows to the top of a hill. There were more than fifty of them. When the soldiers left us, we decided to serve ourselves first. That’s why, when the soldier gave me the order to kill, I did it. I wanted to do it, because I wanted to have cows. I thought I would never in my life have a cow. I took only one for myself. I was afraid, because it was stealing. Imagine if the soldiers found me taking their cows!

The next day, we were recruited again. We went from empty house to empty house, looking for Tutsi hiding inside and taking anything they’d left behind. I found one man, Rwikangura, and I killed him, because we were told to wipe them out. And because when I looked around, I saw things I wanted to take. And because after killing fourteen Tutsi, I no longer felt scared.

The third day, we went to another place, and I killed a child and his mother. The fourth day, I went to chase Tutsi in the Nyiragongo swamps. This is how I met Alice.

Alice: After the plane crashed, the road out of Nyamata was blocked by the soldiers and interahamwe. We couldn’t escape, so my husband and I and our nine-month-old daughter, Fanny, fled to the church. It was packed with people. My mother was inside; she told me to stay outside so the baby could breathe.

There was a big mass of people outside the church, too. My husband was preaching. Some men asked him to go and fight the interahamwe with them, but he said he would fight them with his Bible. Everybody who could teach in the name of God was doing it. We preached, we sang. We prayed any way we could think of.

On April 11, the interahamwe attacked the church. They killed my mother and two sisters. My husband and I ran with our daughter to a bean field. That night, we slept in a school. For seven days, we hid among bean plants and banana trees during the day and slept in the school after the interahamwe left.

When the interahamwe set fire to the fields, we ran thirty kilometres to the swamps to hide in its grasses. My husband ran to one side, and I ran to the other. But the interahamwe were not far behind, slinging their machetes back and forth through the reeds, trying to hit anything. This went on for ten days.

I had Fanny on my knees, and my niece next to me, when a soldier finally found us. He looked at my baby and said, “She’s beautiful. She must be the child of Fred Rwigema,” who founded the RPF. “Where is this baby’s father? Did he run away? ”

“I don’t know,” I lied. “I left him two or three days ago. He might not even be alive.”

Then he took all my clothes.

“You know,” he said, “your government has abandoned you. I can kill you.” He had a machete in one hand and a club in the other.

I told him, “Do what you came here to do.”

He shook his head. “My arms are not made for spilling the blood of people.” Then he left.

Later, a whole group of them came back. They took my baby from me. They threw her in the air, and they cut her in two, down the middle. I fell down, crying. They started hacking me with machetes. They drove a spear through my shoulder and struck my head with a club studded with nails. They left when they thought I was dead. I heard my niece cry, “This one, now she is dead, too!”

An old woman appeared, a Hutu neighbour who had run with us because her husband was Tutsi. She saw and heard everything that happened to me, and she took her head wrap and tried to reattach my hand with it. Then she took more fabric from around her waist, and we wrapped up my baby. I was too injured to move, so she left with my baby. From there, I can’t remember anything. I died for five days.

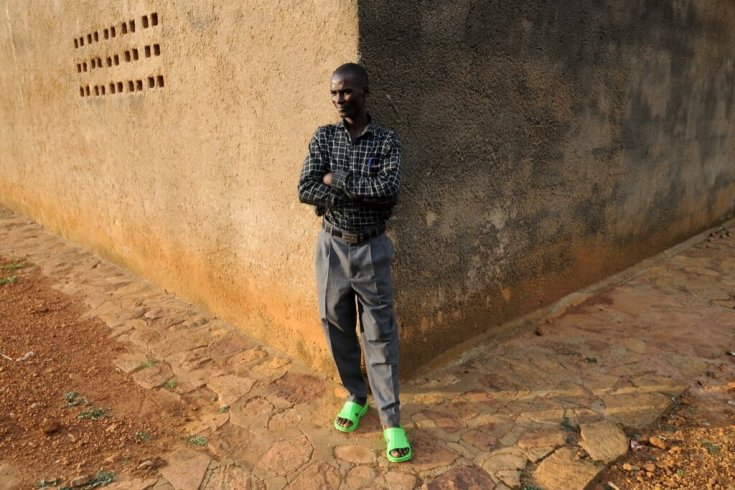

Emmanuel: Alice is the last person I cut. I cut off her hand and made a scar on her face. I thought I killed her. And then I stopped killing. Something had begun to bother me.

I was a singer in an Adventist church, and there’s one song that says when our time comes, all the riches we’ve accumulated are not going to follow us, and that the person who spends his life pursuing them will only attract Satan. Partly, I was afraid of Satan.

I was also fed up. I saw the faces of all of the people I killed before me. I remembered I had sung in front of them in church. I thought, “How come I killed the same people I was singing for? ”

It was time to stop. Still, I had already taken their things, and I decided those things would stay in my house.

Alice: I woke up in the swamp, with lots of dead bodies around me. They smelled, and dogs were eating them. My husband found me there. He told me they had thrown him into a well; he’d had so much water in his body that they had to pump it out of him.

Then he showed me our baby. “We’re going to have to bury her,” he said. But there was no place to bury her properly. We could only cover her up. I still can’t bury her, because I never want to go back there.

While I was unconscious, the inkotanyi had taken control of the district. Now they were asking the able-bodied to come out of the swamps and join them. Still very weak, I stayed there for two more weeks, until my husband could get me to a hospital. It was mid-May when he carried me out of the swamp on a door.

When I left the hospital two months later, we moved into a house shared between ten families. We eventually got a house of our own with help from the government, and some of my husband’s relatives who had returned to Rwanda stayed with us. They didn’t understand what happened; they didn’t live through it. They told my husband I was handicapped and would not be any good to him anymore. They asked him, “Will you wash your kids’ clothes? Will you be the one to raise them? Let us find you a new wife.” My husband looked at me like I was useless. But he told them, “What happened to her could just as easily have happened to me.”

Emmanuel: After the inkotanyi ended the genocide in Rwanda, they formed a new government. In 1996, I went to a district court to turn myself in. I started to tell the judge what I did, but I was talking so fast, like a crazy person, that he asked if I was sane. I said, “I can’t cope with it anymore. I just want to be forgiven.” Then he asked, “Who are you asking for forgiveness from? You killed almost everyone.” I answered, “Since there is nobody left, I am asking forgiveness from the government, because I killed its people.”

A month later, they sent me to prison. I went with my father. We were packed like beans, one under another. Of course, people were beaten. The police told the guards that I had confessed and that they should be nice to me. I was allowed to work outside, cooking and cleaning for the policemen. My father, who did not co-operate with the courts, died from sickness in prison. I was there for seven years, until the amnesty. Paul Kagame, the president of Rwanda, said that anyone who had confessed could be freed.

Still, if somebody killed your family and then got out of prison, you would be unhappy. At the same time, if you had killed you would not be comfortable facing your victims. That’s why four ordinary people in Nyamata started an organization called Ukuri Kuganze Guharanira Ubumwe n’ubwiyunge (May Truth Bring Unity and Reconciliation). I joined in 2005. We wanted to have a place to talk and to plan how we would build a future together, so we borrowed some land, and together—hundreds of us—we raised crops and animals and built houses.

Alice: I didn’t expect to ever meet Emmanuel. I didn’t even remember his face. My neighbours pushed me to join the association because I stayed at home too much. I lived in my thoughts about the genocide and about the problems I still faced. I knew this group was for people who survived and people who were getting out of prison for genocide. I wondered how we could accept these people into our communities again.

Emmanuel: I remembered Alice’s face; I’d kept it in my mind. When I first saw her, we were making bricks for a new house. I wanted to talk to her. But I was also scared of her. Every time our eyes met, I wanted to run. I had no idea how to approach her.

Alice: One day, Emmanuel brought some sorghum beer and some sweet potatoes to the field where we volunteered. This was for ubusabane, or sharing, which gathers a crowd and puts them in a good mood. He started by grilling the potatoes; he took the biggest one and gave it to me, saying, “This is for our secretary.” We all drank and danced.

Then he asked if he could talk to me. “I have something to tell you,” he said. “I have a big problem.” He kept repeating this. “I have a big problem, I have a big problem.” After twenty minutes, he fell on his knees and asked me to forgive him.

“Why? ” I asked him. “We are friends. What do I have to forgive you for? ” He just kept saying, “Forgive me, forgive me,” and I kept asking why. Finally, he said, “I’m the one who cut you.”

“What did you say? ” I asked him. He repeated, “I’m the one who cut you.” I asked him to tell me where and when. He did; his story was all true. So I left him there, on his knees, and I ran for miles.

Emmanuel: I thought ubusabane would make it easier for Alice. After prison, before going home, we went to ingando, re-education camps where the government teaches unity and reconciliation. Some people who’d had a chance to ask forgiveness from survivors found they could be traumatized by it, acting like someone who’s gone crazy. At ingando, they told us that when we asked for forgiveness we should find a way to do it so that they could be held by their friends if they needed them.

Alice: For Emmanuel, it was easy, because he was ready to ask. He had prepared his heart, and he had prepared a way to do it. I was in shock. I didn’t say if I had forgiven him or not. I couldn’t really answer either way. So I left him in a place that was not comfortable for him either.

After I left, a woman found me. She took my hand and led me home. She told my family what happened. My husband said, “This is your fault. Why did you join an association with killers? ”

I spent one week thinking about it all the time. People sometimes asked who had hacked me, and I couldn’t answer them. But I knew I wasn’t born like this! I needed to know who did this to me, because I was judging everyone around me. The people living across from us—they took a lot of our things, so maybe they were the ones? I wanted to forgive and live normally with people again.

Still, I had a hard time when Emmanuel revealed himself to me. It took me back to 1994. My husband reminded me, “You promised God that if you found out who did this to you, you would forgive him. Why are you hesitating? ” So when I went back to work, I was the first one to greet him. I told him, “I forgive you. God will forgive you.”

Emmanuel: Even though I didn’t know if Alice would accept, after I said “Forgive me,” everything was easier for me, even eating. For the first time in a long time, I felt the food go into my stomach. Before, I had no appetite, even when my stomach was empty. It was like a huge stone was lifted off me, and my neck could stretch and my head could rise up, because the stone was not there anymore.

Now we are close friends. When I need something and she has it, she will give it to me. If I have something more than she has, I will give it to her. We can sit down and share food.

Alice: I forgive Emmanuel, but as Emmanuel, not as a Hutu. It’s not the same with all Hutu. I will not forgive those who have not come to ask. Some of them pray in my church. I know the ones who chased us from our home, and those who came to kill at the church. Others, I’ll never know. Like the one who killed my child.

My husband will not forgive Emmanuel. To forgive, you have to have something in common, like the projects we have in the association. My husband hasn’t shared that kind of experience. He dislikes anything that reminds him of those days. He still will not listen to Rwandan radio, only to international news. He doesn’t want me to talk about what happened either, but I don’t always have to do everything he says. For me, talking about it helps. This is why gacaca, the local court held outside on the grass in every community in Rwanda, has helped me. Since most Rwandans can’t travel to the international tribunal in Tanzania, these trials help us all learn what happened.

The surprising thing about gacaca is that when people like Emmanuel tell the truth, the survivors come to love them, while the Hutu who worked with them during the genocide start hating them.

Emmanuel: There is tension between those who have confessed and those who have not. Some months ago, my daughter was sick, and the hospital could not figure out what was wrong with her. The traditional doctor said she had been bewitched. I think it came from someone who is angry that I confessed.

Before I went to prison, my wife heard me giving testimony about the house where I killed fourteen people, and she went home completely changed. Now when we argue, sometimes she says I might kill her. So we don’t talk about it.

I did tell my daughter about it. I told her that I fell into sin, a big sin, and she should know about it so that she does not fall as I did. I don’t give her details; I usually say we were in a group and we killed some people. We didn’t know it would haunt us.

Even today, I see the faces of the people I killed. They pass before my eyes without speaking to me. I think they are silent because the dead can’t forgive. Can you imagine? You killed someone you don’t even know, and he passes before your eyes, and he will never talk to you.

Alice: My kids ask what happened to my hand. I tell them the devil came to Rwanda. I say there was a war, and the government told the Hutu to kill the Tutsi. When they ask me how they can recognize a Hutu, I change the subject.