Trish Lindström

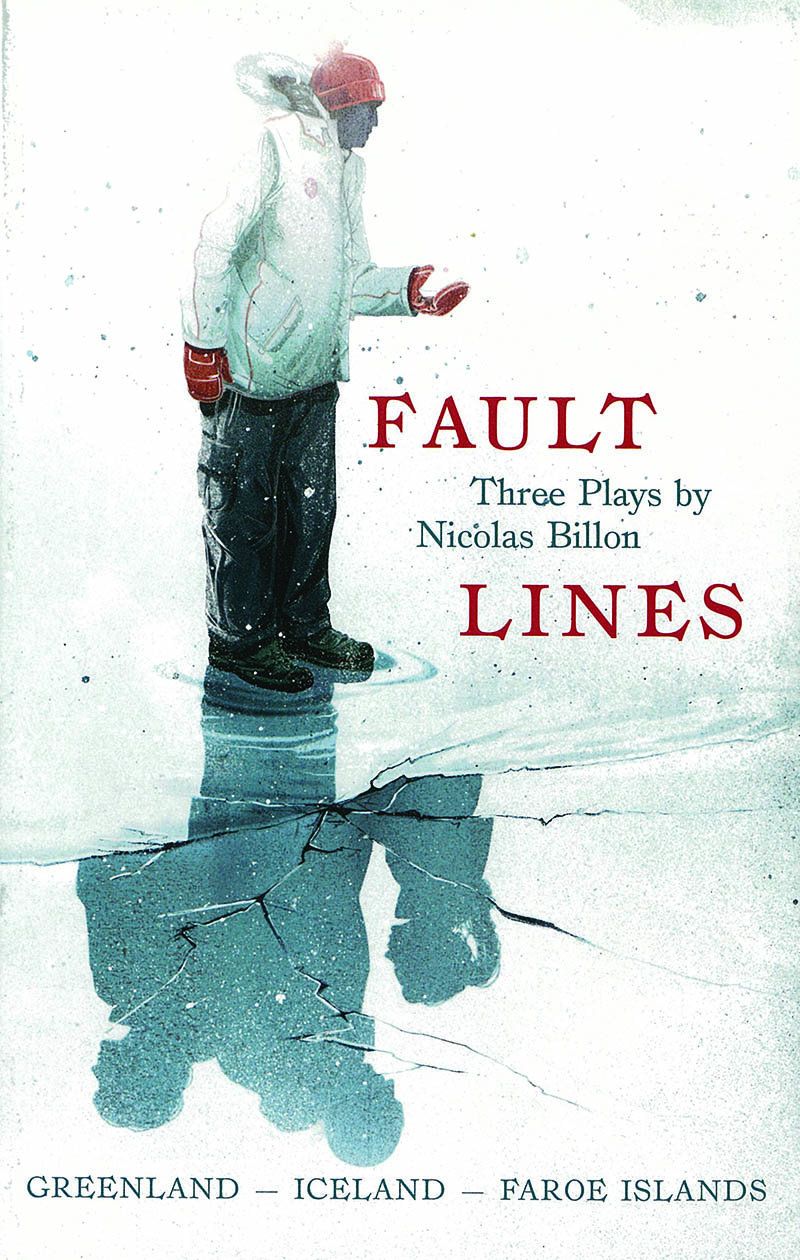

Trish LindströmNot all of the rifts that inform the title of Fault Lines, Nicolas Billon’s collection of three plays, are tectonic in nature. Many of them begin as tiny cracks, innocuous fractures of psyche or resolve, interruptions of thought or life path. When Billon finds these fissures, however, he presses into them eagerly, exposing vulnerabilities in his characters and flaws in their plans.

While the three plays that make up the collection, each named after an island—Greenland, Iceland, and Faroe Islands—are certainly not devoid of action, these brittle moments often take place before the characters’ epiphanies, whether powerful or painful, begin to translate into action or have an impact on the world around them. We get to see the first crack crawl across the glass of a character’s mind well before it finally shatters. Fault Lines is both shockingly intimate and utterly merciless. It’s also the winner of this year’s General General’s Literary Award for Drama.

Natalie Zina Walschots: What was your reaction when you received the news that you had been nominated for a GGLA? And what was your reaction when you won?

Nicolas Billon: It’s funny, because I’ve gotten the question, “How do you feel about winning? ” a lot. It feels great! I really don’t know how else to express it other than that.

Natalie Zina Walschots: All three of these plays engage with the idea of fracturing or cleaving in an entirely different way, from hairline cracks to massive crevasses. What is it about these moments of psychological or personal breaking that fascinate you?

Nicolas Billon: They’re moments of high drama, but those moments are not necessarily externalized. They are realizations. There’s a real shift inside how a person views the world, and I am really interested in that moment. The real difficulty with theatre is how to make something internal, external. In fact, when I first wrote Greenland, one of the things Ravi [Jain], who directed the play, and I talked a lot about was that we were really exploring the monologue. Neither of us had worked in the monologue form before, and what I was particularly curious about was this relationship that it creates between the audience and the actor, because there is no fourth wall. It is a direct address.…I find this interesting on several levels, one of which is that it can only happen in the theatre. You can’t really do it in film. I was curious about the intimacy that creates between character and audience.

Coach House Books

Coach House BooksNatalie Zina Walschots: Would it be fair to say that, in these three plays, you’re interested in exploring these moments of fracture, and how they serve as moments of epiphany rather than action? It seems like we’re seeing moments of change take place internally, before they are translated into behaviour.

Nicolas Billon: Yeah. I think that’s especially true for Faroe Islands and Iceland. Greenland is probably a slower burn than the other two. It’s great to hear that, because I always learn so much more about my plays by what other people say about them, [rather] than what I set out to do or think that I am doing.

Natalie Zina Walschots: Why islands? What is it about these geographic landscapes that draws you? Is it the sense of isolation and forced independence? Defensibility and vulnerability?

Nicolas Billon: Your description of the island, to me, is a description of what it was like growing up. I’ve always felt a pull to islands. I grew up essentially on an island, in that Montreal is an island, but that is kind of a stretch. I have definitely always been fascinated by islands, particularly very small islands. I bought a book the other day, that I am so excited to read, called Atlas of Remote Islands: Fifty Islands I Have Not Visited and Never Will by Judith Schalansky. A lot of the islands are miniscule. I’m fascinated with this idea of solitude, but within something larger. It’s not about being on a different planet, but a different island.

I would say of the three plays, Greenland is the most personal. One of my favourite passages in the whole book is at the end of that play, when [one of its protagonists] is talking about this totally absurd dream that he’s had. In performance, sometimes it gets a laugh, and sometimes it gets total silence. It depends so much on the audience. And that’s fascinating to me.

Natalie Zina Walschots: In Iceland, you’ve created a truly reprehensible character in Halim, who is at once tremendous charismatic and an appalling human. What was the process of working on his character like?

Nicolas Billon: I have a soft spot for Halim. He’s a great rationalist, even though I may not agree with him or any of his politics, I have to admire his single-minded dedication and focus.…One of the things that Ravi was very insistent about, and he was completely right, was saying that, “[Halim] has to say things that we are totally repulsed by, and kind of in agreement with.”

Natalie Zina Walschots: All the moments when I became most disgusted by Halim were the moments when I began to be convinced by him.

Nicolas Billon: Kawa Ada’s performance of Halim is so good, so good, and what is fascinating is that Kawa is the exact opposite of what Halim is. In fact, some people who knew Kawa had trouble believing that it was him, because Halim is so not who he is.

Natalie Zina Walschots: Which is one of the wonderful things about drama—you can become the monster and then return to yourself.

Nicolas Billon: Absolutely.

Natalie Zina Walschots: As you’ve said, you work heavily with monologues in your plays, with character interactions being treated like breaks—fractures, fault lines of their own. Characters interrupt each other, or interrupt themselves. How did you employ interruption as a narrative or dramatic device in these three plays?

Nicolas Billon: I didn’t plan the interruptions, they just came out of whatever was coming. When other characters interrupt, it’s pretty straightforward, and up to the storytelling. When it comes to the characters interrupting themselves, I think it’s that thing where, as you tiptoe towards something that is uncomfortable, the closer you get, the more winding your path seems to be.

I also love digressions. I like to surprise. If the narrative is too A to B to C to D, there’s something that becomes repetitive, and so its nice to break the storytelling motion by veering often, even just momentarily, for a little promenade.

Natalie Zina Walschots: I’ve read repeatedly in reviews for all three of your plays this idea that you take remote concepts—rationalism, activism, inequality and the economic collapse—and give them faces and voices, make them specific and personal. Do you agree?

Nicolas Billon: I loosely agree. In each play I had a question. In Greenland, one of the places it originated from was the question, how is it that the scientific community is in agreement about global warming, and yet nothing is being done? But that’s not what the play is about. It’s just the thing that starts the engine. Then, the thing gets a life of its own, and the characters figure themselves out. In Iceland, it was the banking crisis of 2008—and, for me especially, having also lived through the dot-com bubble. I [had] seen this movie before. This was not new. It’s totally cyclical. And Faroe Islands is all about armchair activism. Online petitions drive me crazy.

I am fully aware that the complexity of these issues can’t be reduced to three monologues. I tried to understand what happened in 2008. I read a great number of books, and after all that research, I feel like I’m just starting to get it, because the complexity of it is totally absurd. And that impenetrability is part of the problem.

Natalie Zina Walschots: Throughout Fault Lines, you not only find these hairline cracks, but also place pressure on your characters to widen them or make them more apparent. Was this a strategic choice? How do you apply that pressure?

Nicolas Billon: If you don’t have any pressure, then you don’t have much drama. That’s the fun of it, to poke and prod. In terms of how I do that—I’m so inarticulate when it comes to process, because I am still figuring it out. When I’m in it, it happens, and I don’t have many memories of that time. I exit, and then I look, and there’s something there. Sometimes it’s great, and sometimes it’s awful. I wouldn’t be able to tell you why Jonathan decides to talk about having a frozen woman at the end of Greenland. I don’t know where that came form.

Natalie Zina Walschots: What are you working on right now?

Nicolas Billon: There are two big projects occupying my head space. One is that [a film adaptation] of The Elephant Song, which was my first play, is in the process of shooting right now. It’s great, but there are daily changes, so I feel like I am constantly playing catch up. I am also working on a new play. I’m on a third draft with that, and I am greatly excited about it.