Early in the pandemic, during a weekly Zoom management call, my three-year-old son decided to drop his pants and pee in the middle of the room—right before my turn to speak. “There’s a reason why we pay $2,000 per month for daycare,” I told my wife after cleaning up the puddle.

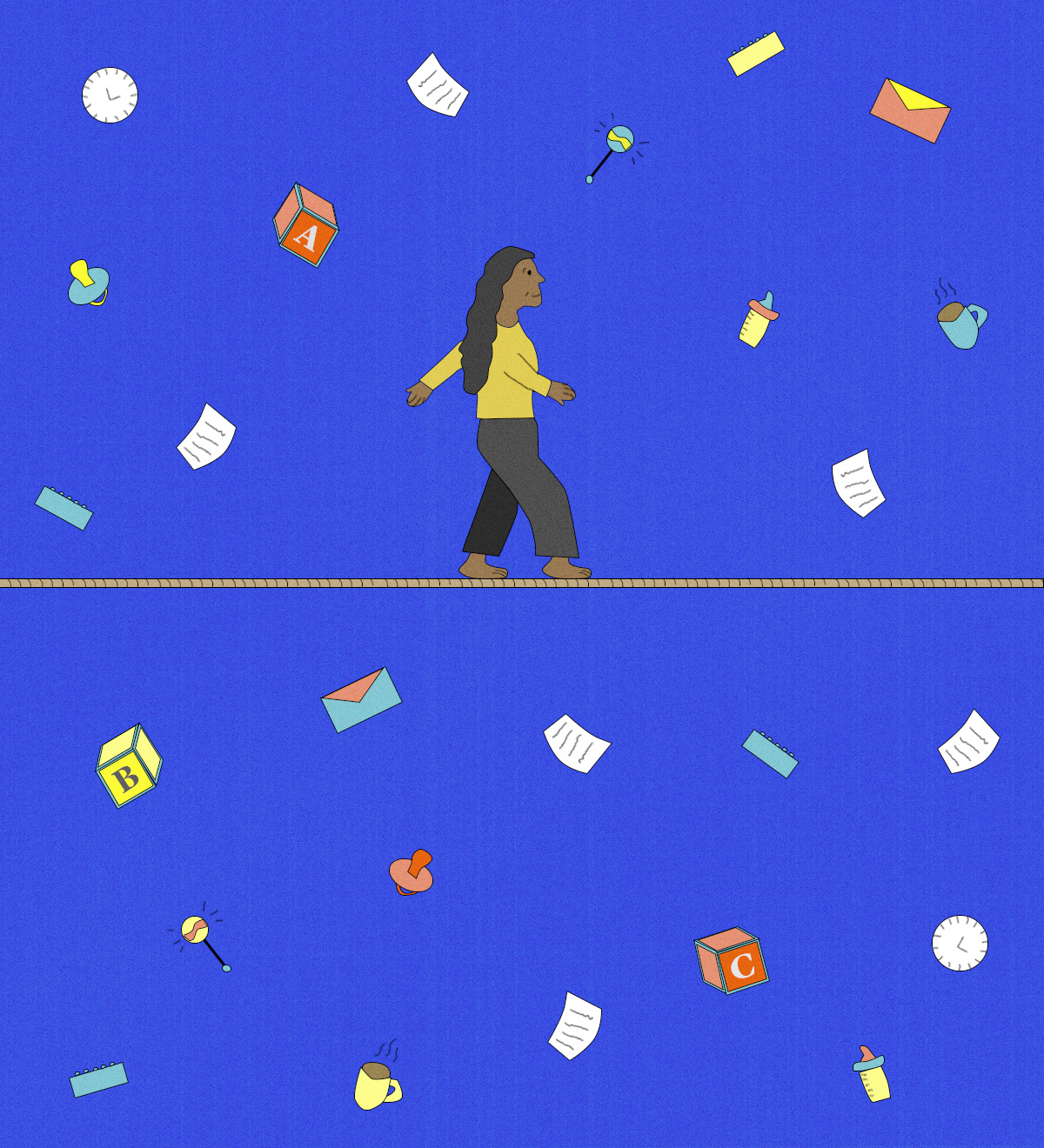

If the pandemic has taught us anything, it’s that round-the-clock child care and a full-time job don’t mix. For those with young children, this means the on-duty parent can’t focus on anything for more than ten consecutive minutes. It means work tasks take three times as long. It means scheduled meetings are interrupted by bathroom breaks or accidents. Parents will tell you there is one hack that can help you meet a deadline or decompress, but it comes with a steep price: hand your child an iPad and you can feed your work machine for hours, but beware the tantrum that comes with ending extended screen time.

It’s challenging for any parent, but the new reality also threatens to set the workplace back decades, according to economist Armine Yalnizyan, a fellow at The Atkinson Foundation. “We are likely to see decades of gains in pay and employment equity rolled back for women.”

As job losses in the service industry started to mount, Yalnizyan coined the phrase “she-cession,” referring to how economic hardships, at least at first, took aim primarily at women. But involuntary job losses are only part of it. Yalnizyan worries that, if women—who tend to handle the burden of child care anyway, even when they work outside of the home—are forced to give up paid work to take care of their children, the economy is in for a bigger hit. Dual-income families are the norm in Canada, and household spending accounts for 57 percent of GDP. Indeed, the number of Canadian families with two employed parents has almost doubled in the last forty years, going from 1 million to 1.9 million between 1976 and 2015, according to Statistics Canada. With the future of daycare and school still uncertain, households will have to make hard choices about who works and who focuses on child care.

And, if household spending drops by a significant margin due to lack of child care options, it will have a profound economic effect. “Without women returning to work, we don’t get back to the previous levels of household spending,” Yalnizyan says. “We don’t get back to previous levels of GDP. We are looking at a prolonged, not recession, possibly a depression.”

While it’s too early for studies quantifying the drop in productivity for parents, it’s obvious the traditional vision of a nine-to-five workday doesn’t jibe with current realities. In my case, the schedule goes something like this: get some work done from 7 a.m. to 8 a.m.; then, from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., perform child care duties while responding to emails and joining Zoom meetings; finally, dig into anything that requires sustained thought from 8:30 p.m. to midnight. Repeat for an undetermined amount of weeks (months?).

It’s a high-stress environment—both mentally and physically exhausting. In short, it’s untenable. I imagine most other parents would say the same. “What parents have been doing in the past three months, if they have kids, isn’t really working effectively,” says Sunil Johal, a fellow with the Public Policy Forum. He acknowledges that all of this recovery planning assumes some type of child care will be available to working parents, but it’s uncertain what daycares and schools will look like in the time of physical distancing. Prevailing analyses suggest we’re looking at periods of fluctuating openings and closures until we have a vaccine or achieve herd immunity. A process, caution some, that could take twelve to eighteen months.

With the future of daycare and school still uncertain, households will have to make hard choices about who works and who focuses on child care.

Nobody is suggesting we send our little ones back to daycare before it’s safe or open up schools and just hope for the best. (Although studies in France and Australia have shown that children may not get as sick or spread the virus as much as once feared.) But, in the first few months of the pandemic, I was frustrated by the messaging from Canada’s federal and provincial governments. They didn’t have any serious ideas about supporting working parents. (Sorry, online schooling doesn’t count, especially with young children.) There was a lack of guidance about the danger of babysitters, nannies, or family members offering child care support—until some governments started talking about creating “social bubbles” as an option for people who had been cut off from friends and family. But, again, none of that was specific to child care. It’s been mostly a “keep working and parenting from home” mantra in the daily news conferences.

This is an indication that either our leadership simply doesn’t get it or our economic and educational structures aren’t set up to accommodate the dynamic needs of parents during pandemic and postpandemic times. For many weeks into the pandemic, it seemed the only choices were black and white: open child care centres or keep them closed. The subtleties of how to reopen safely weren’t part of the daily discourse of pandemic briefings. For example, opening schools or child care centres with staggered schedules and reduced capacity could allow for the appropriate sanitization needed to enhance safety while still serving most of the families that need help. It might mean that parents get only a few hours per week of child care, but it would allow proper safety precautions to be in place and offer a small break for parents, thereby boosting workplace productivity and overall mental health. But it never seemed like the child care part of the reopening strategy was fully baked.

Perhaps it was the lack of discussion around the intricacies of child care reopening that forced such a knee-jerk response to the Ontario government’s announcement giving the green light to welcome children back to daycare, with just a few days’ notice, on June 9. Predictably, daycares weren’t ready to meet the enhanced safety requirements in such a short time. The Ontario Coalition for Better Child Care complained that there was no additional funding to reopen safely. The province responded by telling daycares they could take as long as they needed to reopen, provided they met the government guidelines. It looked like the two sides weren’t listening to each other, which left working parents in child care limbo. The lack of consensus means everyone loses: kids, parents, and businesses.

Leave policies need a rethink as well, says Leah Vosko, a political scientist at York University who specializes in labour issues. Right now, we have government aid for those whose employment is affected by COVID-19. If you have to support a relative with COVID-19, or one whose care is no longer available because of COVID-19, then this might make you eligible for the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB). But there’s hardly anything in place that acknowledges the ways parents are trying, mostly unsuccessfully, to do double duty. We need to examine every possible scenario, Vosko says, and make it possible for more parents to take leave when needed. “We need to be thinking about those things and how to recalibrate child care systems so that all parents are enabled to do their jobs.”

The pandemic is also highlighting the importance of universal child care and gender equality in the workplace, Yalnizyan says. “By and large, the norm was one family, one breadwinner per family to keep a family afloat. It is vanishingly rare today that one earner is sufficient.”

As we move forward in this new framework, it forces families to make critical decisions. For my family, it means I burn vacation days here and there just to reset our child care routine, offering more attention and cutting back on iPad time. After all, it’s unlikely children will be able to go to school or daycare five days a week. For other households, it may mean one parent shelves a career to focus on filling the role that daycares once played. Employers and governments need to adjust to this new reality and account for lower productivity from employees who have children—or risk shutting them out of the workforce altogether.