That Wednesday evening in October 2008, there were six of us guys in the upstairs living room, relaxing after a volleyball practice by playing video games and smoking pot out of a long glass bong. We were a couple of months into the fall semester at Thompson Rivers University in Kamloops, BC, with the first game of the season around the corner. I didn’t make the roster that year, but coach was still letting me practice. Most of the squad was new, including recruits from Ontario and Alberta, even Denmark.

Three players from Alberta shared the house—friends and teammates who’d grown up together and shifted provinces to play for the newest team in Canadian Interuniversity Sport volleyball. The latest arrival: Collin Gordon, a six-foot, twenty-year-old from Calgary with an impressive vertical jump. He seemed solid. Better than me at volleyball, anyway. He had a wide, toothy smile and a big, unguarded laugh. He was good at the first-person-shooter game Halo.

We took turns passing around the four controllers, the non-stop “pop pop” of digital gunfire echoed by the gurgle of the bong. A grenade exploded onscreen, killing one of the players: gamertag Gordo1. Collin cursed and laughed, then tossed the controller to me. The character respawned and I ran back into battle to help my friends.

Ifell out of touch with most of the team after we graduated. Their presence in my life was generally reduced to birthday wishes and the odd like on Facebook posts. Most of the relationships were put on indefinite hiatus when I relocated from BC to Ontario in 2012. Friends would fall from my periphery, only to return via social media announcements of nuptials or first-borns. Big news has a way of bringing people back together.

I lost track of Collin until May last year, when big news brought him snapping back into focus. I was on Facebook, when I spotted one of my old teammates online as well. I asked how he was.

“Not to bad [sic], just trying to figure out whats up with collin gordon. Hes in another dimension . . . Check his wall.”

I clicked over to Collin’s Facebook page. At first I laughed, not fully understanding what I was seeing. Then I paused. I read “truth” and “Allah” and “victory.” In one update Collin wrote that he had denounced his Canadian citizenship. I scrolled down to a photo Collin uploaded of himself wearing army fatigues and a head scarf—which the media would later pick up to run with articles about the Gordon brothers.

“wtf?” I typed to my ex-teammate.

“Hes been in syria/egypt/middle east for like a year + now. That isnt him theorizing from canada, thats him in the thick of shit.”

I asked if Collin was Muslim when we were in university; my friend told me he wasn’t, but thought his older brother Gregory was. He told me they had likely gone together to Syria.

Was he heading for trouble? I wrote.

It was way past that, my friend replied. He said CSIS had already contacted him to ask about Collin.

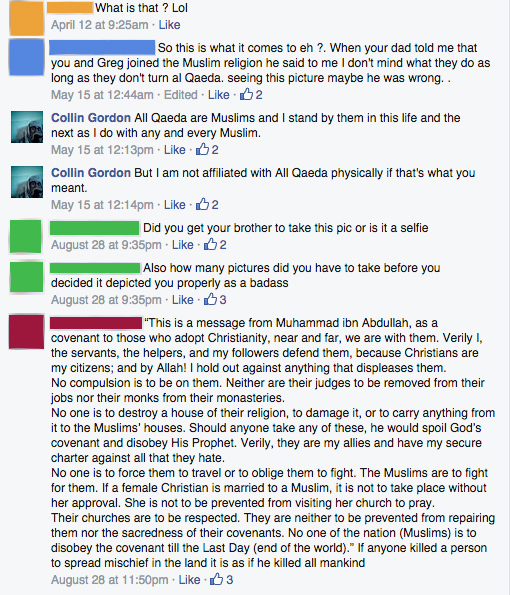

In university Collin posted promotions for parties he had organized and photos of himself with his arm around his friends. Five years later, his Facebook feed was filled with Islamist messages and ISIS propaganda.

I thought about reaching out to him and spilling whatever memory I had into a few paragraphs, in the hope of jarring something in him. But his closer friends, and in all likelihood his family, had already tried without apparent success. My feelings were hard to label: confusion, worry, disbelief, grief. In August, articles began appearing in the media about the brothers from Calgary who’d gone to fight for ISIS.

When I asked someone else from that circle of friends how he felt about the situation, he told me he was past shock and sadness—he was mad and ready to give up. “Shed a tear for the guy when the article came out in the news. But given how long I’ve been reading his threats and hate . . . he makes me angry also,” he messaged back. “How could any person we know get in so much trouble? It boggles my mind.”

Over the following months I revisited Collin’s page every so often, like a painful scab I couldn’t leave alone. It was hard to ignore his posts and the long-winded notes of condemnation below them. Those who had known him before he became radicalized were still there—and vocal. But I also saw comments of praise. His audience had grown to include others who shared his views.

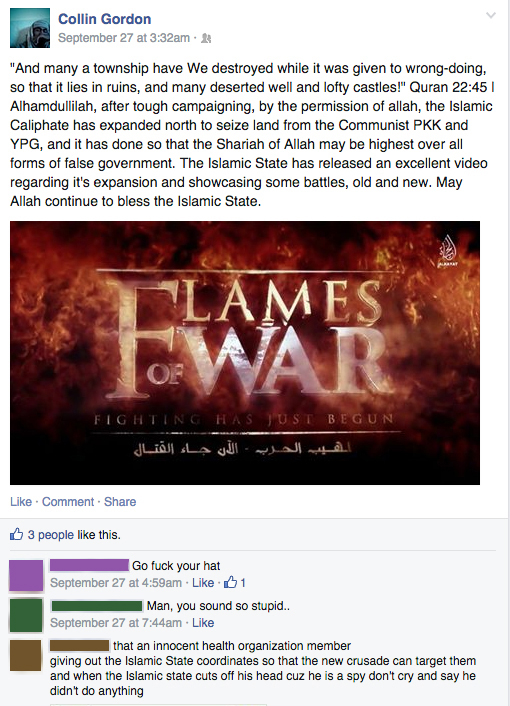

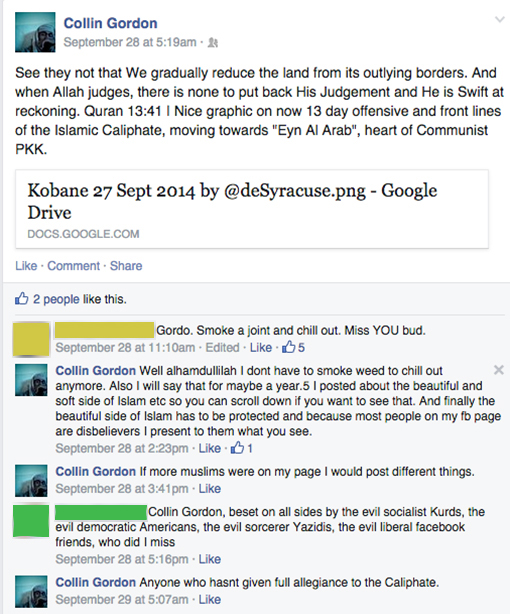

In late September, he posted an image from Flames of War, the ISIS propaganda film. Again his old friends pushed back. The next day, he posted a link to a map of alleged ISIS military victories; wherever he was, Internet connectivity was evidently not an issue.

Isat on the sidelines and watched, at first with the grim fascination of a motorist passing an accident on a highway, then later with the calloused disconnect of a stranger seeing just another shitty event in the world. The Collin I had known was gone.

Then his posts stopped. I didn’t notice at first, it just happened. In February I realized I hadn’t seen anything from Collin for some time. I Googled his name. The first hit was from CTV Calgary: a report that Collin and Gregory had been killed in December, while fighting in the town of Dabiq in northern Syria.

First came a wave of shock for a forgotten friend, then pain for his family and friends, both online and off. I thought about the young man I once knew with a big jump and a big smile. I typed his name once more into Facebook. His profile had been deleted.