Acouple of white film trucks were parked along Bishop below Ste-Catherine, where the smell of a cigar transported me back to an unexpected corner of the past: the remembrance of my father smoking Dutch cigarillos at his desk until the large ashtray was filled with their broken ends. Then he’d be at it again after dinner, or driving between Montreal and our country house in the Eastern Townships, in the Jaguar with his driver’s window rolled down. We never minded the smell, never minded at all. It was his smell, the smell we so associated with him. As children growing up in England in the ’60s, we’d launched a campaign to stop our parents’ smoking, my brother Daniel inserting into my father’s tins of Schimmelpennicks and my mother’s packs of Gitanes little pictures of warning—of the planet drawn as a skull with a cigarette in its teeth, or of the world disappeared in a cloud of smoke. My mother quit. My father… well, living on his island apart, he was a lost cause. Too much on his mind, too much of a patriarch to take instruction easily—least of all from his own kids.

The apartment my parents bought in London toward the end of my father’s life had been my mother’s reward for having returned with him to Canada a couple of decades prior, leaving behind the house in London and the continent where she’d been a model and an actress and had expected to live for the rest of her life. By the time of its purchase, my father was in his sixties and had already been through one bout with cancer, and the benefit of the deal for him, he told me later, was that he’d be allowed to smoke one cigar—a Romeo y Julieta, or a Montecristo no. 4, his preferred—for each Atlantic crossing they made. On one such trip, he and I met up with my mother and my sister Emma in the grand bar of the Langham Hilton on Portland Place. Our conversation came round to one of my sister’s close friends, who was living in Cairo with her Jordanian boyfriend. His uncle, Emma reported gravely, had been on the parade stand when, in 1981, Egyptian president Anwar al-Sadat had been assassinated.

“He’s finding it very difficult,” said Emma.

“Oh,” said my father. “He’s the sensitive type.”

My mother, reproaching him, said, “You’ve had two cigars.”

“How do you know?” asked my father, surprised.

“I can smell it in your hair,” she said.

My father looked across at my sister and me and winked. “Next time, I’ll wear a hat,” he said.

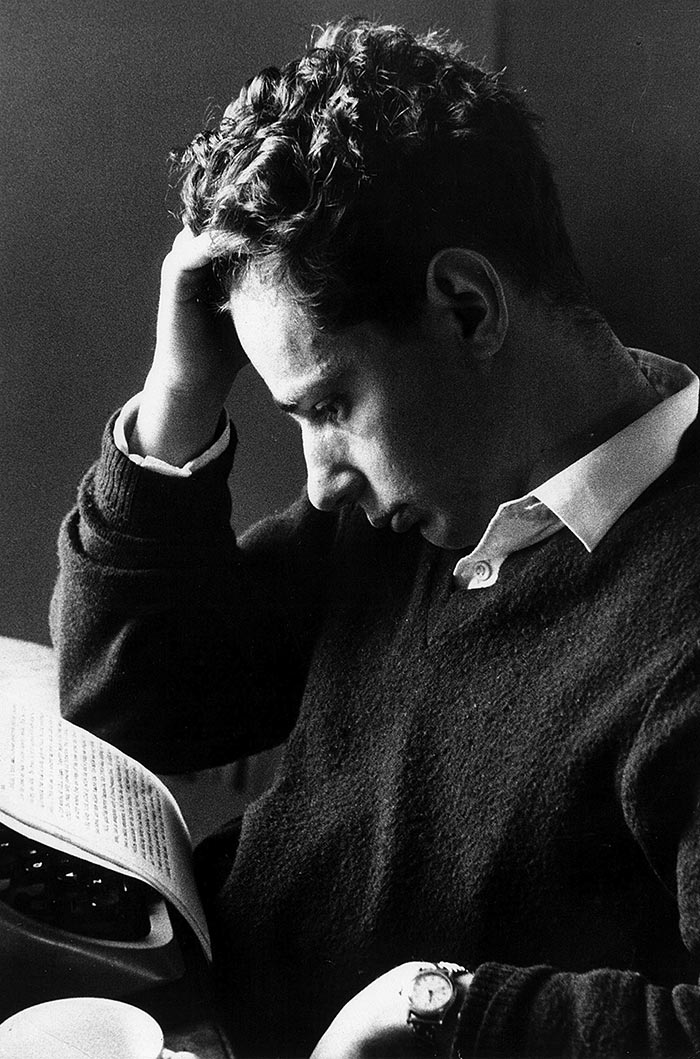

It was funny then, though after his second cancer less so. He quit for a time, but it did not take long before I found him on the patio of our house on Lake Memphremagog, not yet ten in the morning, having a cigar with his black coffee. He turned as I came down the steps and motioned me to the chair beside him, the two of us settling in to look at the glassy lake for a while. He raised the cigar to his mouth a little sheepishly but clearly for me to see. He’d been smoking just two a day for a while, but lately his will had been breaking. The look he gave implored me to say nothing. It said: I tried to quit, but I can’t. I don’t know how.

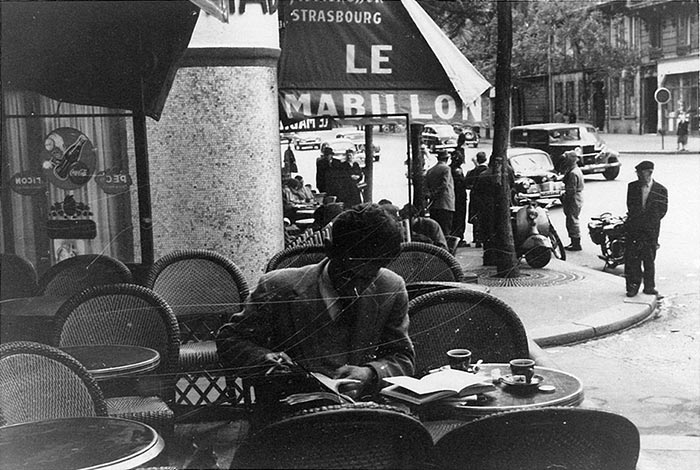

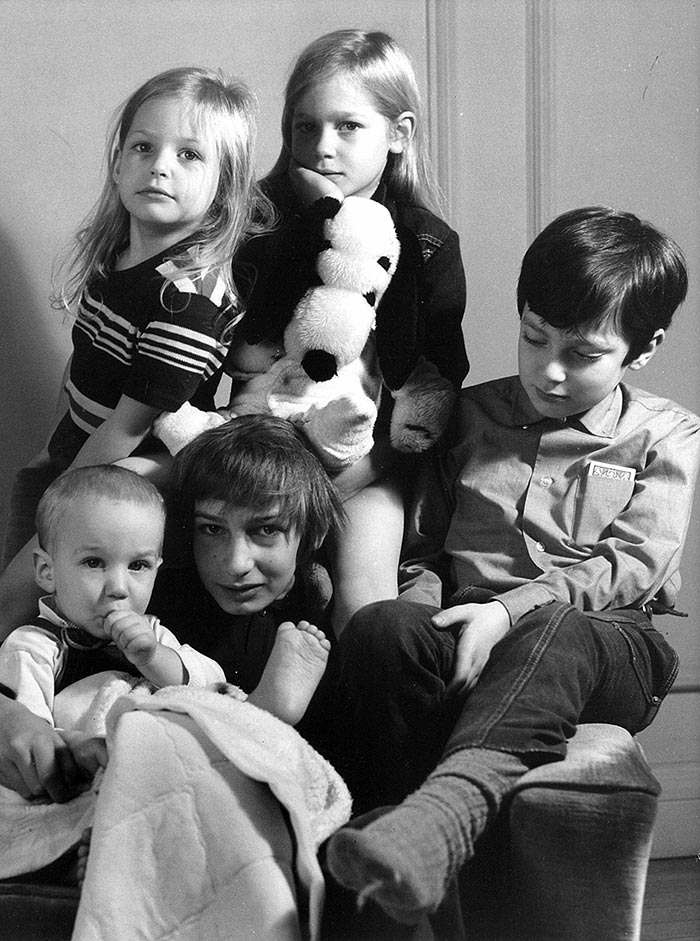

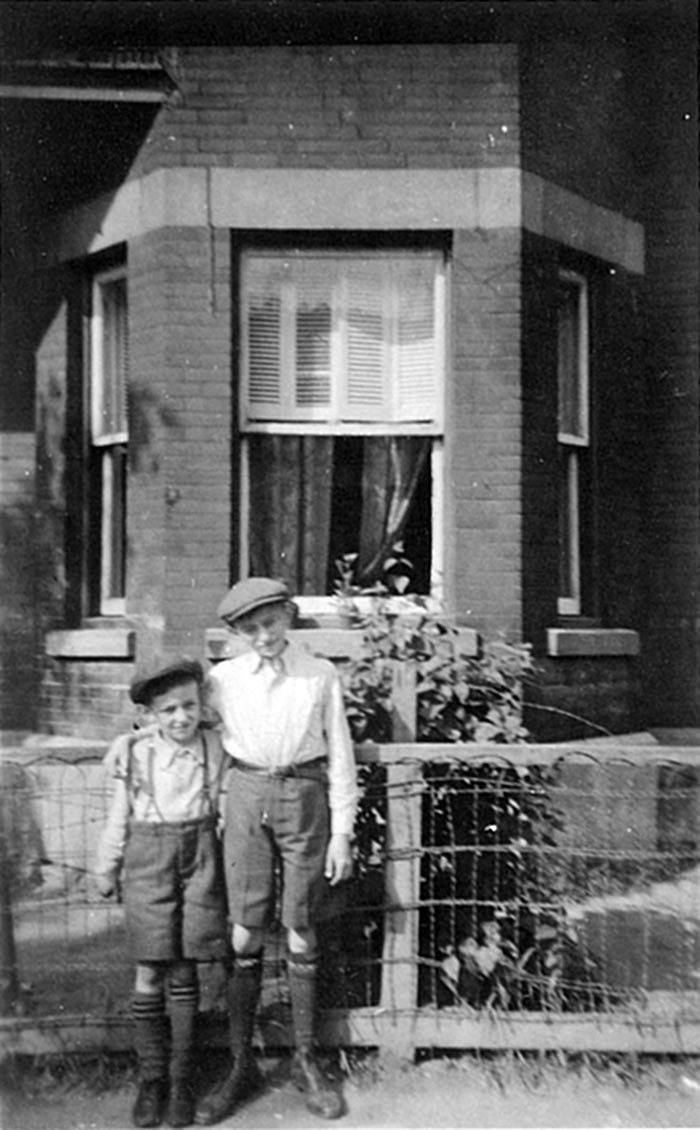

I’d come to Montreal to drop in on the making of the film of my father’s last novel, Barney’s Version. The production was camped outside Grumpy’s, a bar just a few blocks away from the apartment at Le Château, opposite Holt Renfrew at Sherbrooke and de la Montagne, that my parents moved to after most of the kids had left and they’d sold the house in Westmount. My mother, an adopted child who’d grown up in Pointe St-Charles, one of the poorer parts of the city, would tell us how she used to pass the imposing building, with its copper roof and faux turrets, and dream of living there one day. The idea seemed absurd to her then, but later, when she was working as a model for Eaton’s and Chatelaine in Toronto and Coco Chanel and the House of Dior in Paris, the world started opening up to her wonderfully. It was in London in 1954, the day before his wedding to Cathy Boudreau, that she met the somewhat terse, occasionally pretentious but brooding and impressive man who was my father. She was apartment-hunting with the playwright Ted Allan, a lifetime friend, and was married to my brother Daniel’s father, Stanley Mann; my father had moved to London after sojourns in Ibiza, the south of France, and then Paris. Six years later, she married him.

Barney’s Version, like his earlier novels St. Urbain’s Horseman and Joshua Then and Now, draws on my parents’ exemplary love and what, even to his death, struck my father as the wild unlikelihood of having been able to love and raise a family with this striking woman. From Jake Hersh’s beloved wife in St. Urbain’s Horseman (“Nancy. Nancy, my darling”) to the third Mrs. Panofsky of Barney’s Version (“Miriam, Miriam, my heart’s desire”), there exists in his work a portrait of the shiksa wife as love object that his author hero is stunned to have acquired but also believes, in some buried and persecuted Jewish part of himself, he is besmirching. Truth be said, to equate my father with the narrators of his novels is to ignore the myriad ways in which a writer supersedes the mere imitation of reality in his fiction, though my dad was sufficiently aware of the tricks a writer plays that he could make fun of this idea. To wit: when my sister Emma published her first book, Sister Crazy, a set of linked short stories that I’d found hugely enjoyable but that the Canadian press had mostly treated as thinly veiled autobiography, I’d suggested at lunch with my mother and father that perhaps her collection would have been better received had it been described as a fantastical memoir.

“Oh, no,” my mother said adamantly. “It’s a novel.”

And I thought, “Well, sure it is. The mere arrangement of experience into a story makes it a fiction even before whatever of the novelist’s other processes come into it,” though I’d not even concluded the thought before my father added, “But don’t worry—you come out looking pretty good.”

The line between what is fiction and what is not can be vague, and it speaks enough to the way my father drew from his own life in Barney’s Version that within the family we discussed, in particular, the producer Robert Lantos’s choice of the British actor Rosamund Pike to play “Mom,” rather than “Miriam,” and thought it only good sense that the two women should eventually meet. And in Montreal they did, at a dinner Lantos himself arranged before the shooting started. (The family, I should point out, had nothing to do with the making of the movie, beyond being the production’s well-treated guests.)

The apartment at the Château was my mother’s choice, and my father was comfortable enough in it, mostly because of its proximity to a couple of his regular haunts. When he was still living in Westmount, in the ’70s, he would take the much longer walk down the stone and wooden public steps that flank Mount Royal and descend through the woods and by the glorious houses that mostly anglophones used to occupy. Then he would continue along the streets of downtown and on to the Press Club at the Mount Royal Hotel on Peel, a bar for journalists with a gradually diminished franchise that later moved to a tawdry penthouse location at the corner of de la Montagne and de Maisonneuve before it finally folded. There were two English daily newspapers in the city then, the Star and the Gazette, and a baseball team in Jarry Park; the Canadiens were contenders, and, to a Montrealer like me, kids from Ontario seemed downright strange. (I remember, aged fourteen, meeting Kelly from Oakville, who was definitely neither Gallic nor Jewish and seemed like a character out of an Archie comic, with a button nose and freckles and so incredibly white.) But after the Parti Québécois victory of 1976, and then the narrowly defeated referendum of 1980, the economy collapsed and the Anglos took flight, and even the old Maritime Bar at the Ritz, my father’s favourite, closed—this, long before the building was shuttered up to be turned into condos, still a construction site when the film crew moved in to restore it.

In Jacob Two-Two’s First Spy-Case—the third in my father’s trilogy of kids’ books—Jacob Two-Two’s mother asks the dad why he puts up with Perfectly Loathsome Leo Louse. “Because Leo’s an original,” Jacob Two-Two’s father says. The bars my father later frequented—Grumpy’s on Bishop, Winnie’s and Ziggy’s on Crescent—were full of such people, the sorry last stand of dwindling anglophone Montreal in its struggle with the separatists. Montreal’s wealthy anglophones had by and large proved the extremist Québécois absolutely right, Westmounters having shown little or no loyalty to the territory as they followed their money down the 401 to Toronto. The Anglos left behind in these bars were more his type, people who didn’t have the means to leave—and who wouldn’t even if they could have. There was the Irish-born detective, whose partner was a French Canadian (the existence of this wry and unlikely pair having preceded by a couple of decades the comic premise of the movie Bon Cop, Bad Cop); Nick Auf der Maur, the newspaperman-cum-politician turned habitué of Crescent and Bishop streets; Ashok Chandwani and a few other journalists from the Gazette, drinking away their afternoons; and Richard Holden, a man my father regarded as a political turncoat (the elected member for Westmount, he’d left the Equality Party to join the Parti Québécois) but whom he liked anyway.

My dad was in the thick of it, and I was not. For much of this period in the ’80s and ’90s (when Barney’s Version was written), I was living out of the country, and on my occasional trips home I found the old anglophone downtown a broken, dispirited place. There was a seaminess to those bars, impervious as they were to the historic changes being played out a few steps away, in the bright light of the street. But it was entertaining to my father, this atmosphere.

“Hey,” Auf der Maur called out to me from a bar stool at Winnie’s when I’d returned from England for a brief visit. “What’s the worst thing about being an atheist?”

“You tell me.”

“No one to talk to when you’re getting a blow job.”

In these dying bars thrived an obstinate clientele of the down-and-out who sat side by side with city mavericks as well as off-duty (and sometimes on- but pretending to be off-duty) cops; characters whom my father not only enjoyed for themselves but for the work he was doing. They were his “originals.”

Some of this company, as it turned out, came in handy for more than his novels. After my father died, on July 3, 2001, I found myself sitting in Ziggy’s with my brother Jacob—it was the day before the funeral—when Ashok brought over a couple of policemen who sat down at our table. They expressed their commiserations, and then they asked if we wanted an escort for the funeral cortège. (Later we learned that they’d liked our father because he had written about the plight of minorities, such as they belonged to, trying to make it on the force.) I was still recovering from the fact of their having offered rather than asked for something when my unflappable brother said he would talk to Mum about it. They gave us a number to call if she agreed, which she did the next day—it had an odd answering service, like a doctor’s office after hours—and, presto, from Paperman’s funeral home to Mount Royal Cemetery, an escort of policemen on motorcycles, bless them, blocked opposing traffic at every light.

This was the Montreal my father chronicled in Barney’s Version—from the detective colleague who became Sean O’Hearne, the novel’s Sûreté du Québec detective, to the Great Antonio who is inalterably himself, a Croatian-born Montreal strongman with a propensity for thirty-egg breakfasts and towing Montreal buses by a chain. At the bar and joshing, his fellow drinkers were fodder for his stories, just as he was for theirs, though it was also the case that my dad liked to have ports of call where he could exercise his friendships once in a while. His publisher at Knopf, Robert Gottlieb, once told me, clearly bemused, that my father was someone who “simply liked dropping by.” On a recent trip to New York of my own, Charles McGrath, for a long time the editor of the New York Times Books section, said the same, recounting how my father would walk the streets of a city that might as well have been his, a cigar in hand as he ambled between his favourite haunts. “He knew so many people,” McGrath said, as if this in itself was astonishing. When I let slip that during my visit I’d been to the same restaurant twice, he shook his head disapprovingly. “Your father,” he said, “would never have done that.”

In Montreal, after the Maritime Bar closed, the haunts were fewer. If he favoured Ziggy’s, it was mostly because the owner would front him a few hundred bucks when he needed it, as if ATMs and cheques did not exist. He prized, as most of us do, the privilege of being a regular. He liked being someone who could buy the papers at the newsagent’s in London and be recognized by its Asian proprietor, or arrive at a restaurant knowing the right table was ready—all this having been prefigured years before when, in the last lines of his novel The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz, the waiter at his father Max’s local, Eddy’s Cigar and Soda, says to Duddy:

“That’s all right, sir. We’ll mark it.”

And suddenly Duddy did smile. He laughed. He grabbed Max, hugged him, and spun him around. “You see,” he said, his voice filled with marvel. “You see.”

By the time his children had regular places of their own, testing such relationships became one of Dad’s ways of having fun at our, the upstarts’, expense, and putting the father-son order in its proper place—and that, note, would be with the patriarch on top, my father never quite ready to give way. In London, when I was working for the BBC, I made the mistake of enthusing about the French restaurant around the corner from Broadcasting House that I was in the habit of taking my mother to for a fine lunch once a month. My father, fair enough, demanded his own turn. At the threshold of the restaurant’s intimate dining room, he started to stride toward a free table.

“Dad,” I said, and then, foolishly, “we have to wait to be seated.”

At the table, he picked up a piece of bread.

“Garçon!” he said, loudly enough for heads at other tables to turn. My father fixed me in his gaze, grinning more than a little and clearly enjoying, more than I was, destroying whatever favour my custom might have earned me. The waiter approached indignantly and asked if anything was wrong.

“This bread is stale,” my father said.

The waiter removed it.

“French fags are the worst,” my father said.

Jack Rabinovitch, a friend of my father’s since their high school days at Baron Byng, likes to recall how he walked into the Ritz bar one night and my father, who’d obviously been there a while, waved him over and told him, quite abruptly, to sit down and have a nightcap—then a second and a third. Bernard Landry, the Parti Québécois bigwig and my father’s nemesis, was sitting in the far corner. “This is my bar,” he told Rabinovitch. “No way I’m leaving before him.”

Today, at Crescent and Bishop, there may be flat screen televisions tuned in to a hockey, baseball, or basketball game, but the same ’80s rock is being played, and a lot of the bartenders and servers are the same people, if twenty years older. It is my father who is missing—and Ashok, and Richard, and Nick. More trains departing the station. Up the street, Jacques Villeneuve’s bar is rocking for a new generation, and de Maisonneuve, once the ugliest street in Montreal’s anglophone downtown, has been revitalized, but still it is possible to drop into these small black holes of anglophone oblivion.

Grumpy’s is one such bar, and for the movie it didn’t need much dressing. As I arrived, the crew was shooting several takes of Paul Giamatti, who plays Barney, stepping out of a car. It was his cigar that I’d smelled, the actor evidently in character. Then they started on a couple of scenes with Giamatti inside, the first of them scene 176, in which he is sitting at the bar and drawn into conversation with the blonde next to him. “Barney’s downfall,” said Lantos as the crew navigated the camera along its tracks in the small space inside. A bunch of extras played cards at the back until the stand-ins stepped down and the stars took their places. Outside was the “video village”—a black tent with chairs for Lantos; the director, Richard Lewis; the screenwriter, Michael Konyves; and others to watch the live takes on video monitors.

Actors have different ways of coping with the combination of torpor and sudden activity that is a movie set, and Giamatti’s was to pace the pavement wearing a look of almost tortured anxiety. He is a talented, thoughtful actor. His father, Angelo B. Giamatti, was a professor at Yale University and then its president, before becoming the commissioner of Major League Baseball in 1989. His mother was an English teacher, and Paul, who lives in Brooklyn, studied English at Yale before joining its School of Drama. (His brother, Marcus, is an actor, too.) During the filming, Giamatti described himself as a “workhorse,” though he’s infinitely better than that. Immediately, I could feel the furious intensity he was putting into his performance as Barney, slowly being undermined by Alzheimer’s. He did the same in Sideways, the 2004 comedy that earned him widespread acclaim and a Golden Globe nomination; in the title role of the television series John Adams, for which he won an Emmy in 2008; and in Cold Souls, a small independent gem of a film produced by his wife, Elizabeth, in which he played essentially his own existentially wreaked self.

Inside Grumpy’s, the time had come for Barney to sit at a table with his father, Izzy, played by Dustin Hoffman, an actor who has developed a more seasoned Hollywood approach to enduring life on-set. Where Giamatti was either in his character or just uncomfortably waiting, Hoffman was the celebrity at ease. At his side was his assistant, an attractive forty-something woman whose thick blond hair reached to her waist, where she wore a makeup pouch attached to her belt. From time to time, she would dip her hand in to give her star a touch-up. The stand-ins finished, and the assistant director called for Hoffman, who was sitting outside on the wooden steps of the adjacent bar and was totally unfazed when a woman passed by and, recognizing him, shrieked. She asked for his autograph, and he gave it. Grumpy’s is Dink’s bar in the novel, and the next scene was number 84 in Konyves’ script.

INT. DINK’S BAR—DAY

Two scotches on the table. Izzy waiting for Barney in a booth. Barney rushes in and drops down across from his father.

BARNEY: I have to get a divorce.

IZZY: Jesus Christ.

(beat)

Did you cheat?

BARNEY: No.

IZZY: Did she?

BARNEY: No.

IZZY: So what happened?

BARNEY: I’m in love with someone else.

—and so on through Izzy’s offer of a little of his “parental wisdom.”

IZZY: I know how hard marriage can be. In the beginning it’s all briskets and blow jobs and la-di-da, ain’t life grand, and then real life starts. You come home from work and all they want to do is talk and all you want to do is screw and soon enough every day is like pushing an avocado through a cheese grater. It all feels like shit in your hands.

But Hoffman was repeatedly changing the lines, fluffing, forgetting, and diligently keeping at them before finally taking issue. “I can’t do this,” he protested.“‘Briskets and blow jobs ’—this is a writer’s line.”

Outside in the video village, Konyves, a writer who lifts weights, was relaxed and shrugged it off. The Hungarian Montrealer had submitted a treatment for a screenplay on spec, solving the novel’s problematic transformation to the screen and the production’s screenwriting issues at a stroke, Lantos already having spent several hundred thousand dollars on three different scripts, including the original one by my father.

“Is she the one?” Hoffman’s Izzy asked Giamatti’s Barney, referring to Miriam, his new love. “Is she the mother of your children?” And then, not in the pages, “You want to put your head on her breast for all eternity?” before, on another take, “I want to bend her over and point her toward Detroit.”

Konyves remained undisturbed. “There’s a script for a reason,” he said, grinning widely. He was along for the ride and enjoying every minute of it.

More takes.

“That’s why it’s good to work for Clint Eastwood,” said Hoffman, throwing up his arms. “He does two takes and moves on. Everybody looks like shit, and he gets all the kudos.”

Minnie Driver, the Second Mrs. Panofsky, arrived on one of Montreal’s rented bicycles for a look at the actor with whom she would be working on the following day. Hoffman was still at it, more takes were being called for, and I was already feeling admiration for the editor whose job it would be to reap the brilliance in his performance. The director, Richard Lewis, took a pause to observe the action on his hand-held monitor—which was when, sotto voce, Hoffman started to take over, gently telling Giamatti what he should be feeling and how he should be reacting. Clearly, this was difficult for Giamatti, who was already having to do double the work in adjusting to Hoffman’s slip-sliding delivery. “Let’s do a couple of De Niros!” announced Hoffman the entertainer, finally, proceeding to deliver what were actually a couple of pretty good takes in the manner of his Hollywood rival and chum. Giamatti, deferring to the senior actor out of necessity, played along as if nothing was happening, and it was hard not to conclude that Hoffman’s direction was his way of saying, “Listen, buddy, your career may be rising, but I’m the star and there’s plenty of life in me yet.”

When the scene concluded, Lantos laughed it off. “Dustin wanted to play Barney himself,” he said, “but he’s too old. What he did in there was fabulous. I’ve never seen that before. He took Paul to a whole new level.”

Outside, Charlie Foran, putting the finishing touches to his biography of my father, was patiently hanging about for an interview. But it was already four, and Lantos was headed off to his trailer to have lunch cooked by his personal chef, flown in from California, and then to check out the refurbished Ritz-Carlton for the wedding scene—the gilt ballroom and the Jardin du Ritz (complete with ducks) so lovingly restored that the new owners had asked if they could keep the set up and hold a party there. Foran would have to wait.

The next morning, the production moved to Mount Royal Cemetery, the northern masterpiece of Frederick Law Olmsted, the landscape architect who designed Manhattan’s Central Park. This is where my father is buried—and, too, as a Canadian Press travel piece pointed out without irony, the Montreal mass murderer Marc Lepine. So are the Habs greats Maurice Richard, Toe Blake, and Howie Morenz, company that would have pleased my father more. Mayor Jean Drapeau, who gave Montreal the ’76 Olympics, along with a debt it took the city thirty years to pay off, is also buried here, as are the unfortunate Pierre Laporte, murdered in 1970 by the FLQ—and, his grave one of my own points of pilgrimage, John “One-Pound-One” Rowand, the nineteenth-century Hudson’s Bay factor whose last wish was to be buried in Montreal, headquarters of the fur trade, rather than at Fort Edmonton, in the territory beyond “the Canadas.” (His bones were boiled clean and shipped in a barrel of molasses back to Montreal via England.) And let’s not forget Jacob Schick, pioneer of the electric razor, whose entrepreneurial spirit would have appealed to my father and the young Duddy Kravitz, who…

…knew what he wanted, and that was to own his own land and to be rich, a somebody, but was not sure of the smartest way to go about it. He was confident. But there had been other comers before him. South America, for instance, could no longer be discovered. It had been found. Toni Home Permanent had been invented. Another guy had already thought up Kleenex. But there was something out there, like let’s say the atom bomb formula before it had been discovered, and Duddy dreamed that he would find it and make his fortune.

I had not visited my father’s grave much, so before joining the crew I walked up to the high eastern edge of the cemetery, which overlooks the Camillien-Houde belvedere and the city’s east end. The Victoria Bridge spans the Saint Lawrence in the far distance, the Olympic Stadium and the Plateau sit in the mid-ground, and immediately at the foot of this side of Mount Royal is Jeanne-Mance Park, formerly Fletcher’s Field, and the streets of the Jewish ghetto my father had moved away from but never left. It was the morning of September 2, the eleventh day of a three-month shoot that had started the month before in Rome and would move from Montreal to the Eastern Townships and finish in New York in November. The sky was a perfect, summery blue, and the weather so good that the scenic decorators had contemplated painting fall colours onto the heady blooms of the cemetery’s hydrangeas. David Webb, the Canadian-born first assistant director, was standing slightly off to the side. Webb is the man Gus Van Sant, among others, depends on, and his hiring was definitely a coup for the production. His father was in the military; he knows how to be in charge. He’s also a tall man, and when he shakes his head or stretches out his arm to point somewhere or at somebody, as he was doing a lot on this particular morning, his actions command attention.

But when I arrived on set, shooting was at a standstill. Hoffman, Giamatti, Lantos, Konyves, and Lewis were gathered in a scrum by the headstone that was standing in for Barney’s mother’s grave. In the scene, Barney is accompanying his father on the anniversary of his mother’s death when an attractive younger woman, mourning at a grave nearby, distracts the insatiable Izzy—no surprise. The extras were standing by in black dress, and there was a great hullabaloo going on about whether or not Barney would have been wearing a kippah.

“Great!” said Richard Lewis, having noticed my arrival. “So, tell us, would he wear a kippah or not?”

“If he had one in the pocket of his suit,” I replied, recalling my own mad scrambles to find one before funerals and bar mitzvahs, “though I’m not sure he would have had one—”

“That’s right, he wouldn’t,” said Giamatti.

Lantos frowned. Clearly, I had given the wrong answer.

“But he’s visiting his mother’s grave,” I said in quick repair, “so of course he would have done.”

“He’s not religious,” said Giamatti.

“It’s a cultural symbol, not a religious one,” said Lantos.

Hoffman agreed. Giamatti insisted that no, he wouldn’t.

“He would,” said Lantos. “I do.”

“I don’t,” I said. “My father let me out of the house wearing a windbreaker and pigskin running shoes to go to synagogue for a friend’s bar mitzvah. He thought it would be funny. I didn’t know any better.”

“And what about you?” Lantos asked his director.

“I wouldn’t,” said Lewis.

“I’m a bad Jew,” I said.

“Me, too,” said Lewis.

“You didn’t have a bar mitzvah?” asked Lantos, looking my way and frowning.

“No,” I replied.

“Well, I did,” said Lewis, “and I still wouldn’t.”

“Okay, folks,” Webb called out, “that’s the relaxed part of our day gone.”

But the argument continued as Webb hollered across the set that he had five mores scenes to shoot and the production was losing time.

“I’m going to call my rabbi in Los Angeles,” declared Hoffman, showily walking through the grass between the headstones to find better reception. ABSOLUTELY NO PHONES ON SET, I was learning, was one of the rules that distinguished hangers-on and crew from the celebrities and the production’s movers and shakers.

“Quebec politics were nothing,” I said to Lewis. “The most difficult issue in my father’s life was the question of his faith.”

Hoffman ended his call and put the BlackBerry back in the pocket of his khaki trench coat.

“So?” asked Giamatti. Lantos and Lewis looked on.

Hoffman shrugged. “He says maybe you would but maybe you wouldn’t.”

“Well, there’s a Talmudic reply,” said Lantos.

The argument continued for another ten minutes before Webb shouted out that he couldn’t afford to lose any more time.

“No kippahs!” yelled Lewis conclusively.

“Who says you can’t have fun in a cemetery?” quipped Hoffman, apropos of nothing. “I’ll bet you there’s at least one person here who’s been laid in a cemetery!”

“In my gut, I think Izzy would be wearing one,” I said.

“Drop it,” said Konyves. “In the next scene, Izzy’s dead in the massage parlour.”

Lantos, shaking his head, walked back to the video village. “Thank God for CGI,” he said. “We’ll just put them in later. If we can CGI a plane, then what’s two kippahs?” Lewis checked the shot through the eyepiece of the camera as Lantos took the hand of a slender young woman dressed in black and led her to the spot where, mourning with her family at one of the graves farther down the row, she would be noticed by Izzy.

“Where’d he come up with her?” asked one of the crew.

“You have to ask?” said another.

SCENE 149

EXT. CEMETERY—DAY

IZZY: I need to get laid.

BARNEY (walking away): Jesus Christ…

IZZY: What? How long have you ever had to hold out, Mr. THREE wives!

Hoffman tried it again—but with a little extra: “Are you my son? How long have you had to go without? Eh? Eh?” Giamatti waved him off and walked away. “The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree!” yelled Hoffman. “How long have you had to—Jesus, what’s the line—go without? Hold out? Do I have to say it with the h?”

In the video village, Lantos is ignoring the action and on his BlackBerry, organizing a newspaper reply to Naomi Klein’s letter of condemnation for the upcoming Toronto International Film Festival’s spotlight on Israel. “Will you sign it?” he asks.

And then it was Izzy’s turn to die. The setting for the scene where Barney’s father croaks in flagrante delicto was the Abaca massage parlour on the west side of Park Avenue, one of the streets of the old ghetto where Jews and French Canadians and Irish, and then Greeks and Vietnamese, would sit out the dog days of summer on the exterior spiral staircases that are a feature of the city—staircases, according to Catholic Montreal apocrypha, that enabled priests to keep track of the comings and goings of the men and women of their diocese. The parlour, with its blue neon sign and darkened window, lies north of Mount Royal and east of St. Lawrence, on the Main—then the dividing line between Montreal’s francophone working class and the Jews living in cold-water flats. Groups of Orthodox girls were returning from school. Giamatti paced anxiously on the sidewalk. The costumer stepped up to him with a couple of cardigans to try on, like the ones my father would have worn over a plain white T-shirt. Hoffman was sitting on a bar stool having fresh makeup done.

“We’re trying really hard to get Mikey’s script nominated,” he said.

“We’ll have a great DVD of outtakes, that’s for sure,” said Lantos as his phone went off. Vania, Lewis’s assistant, was sitting on the parlour steps working three.

“So what do you do?” Hoffman asked.

I mumbled that I’d written a book about Canada and had travelled the country from coast to coast to coast. I explained how challenging a land it was to know, and that I’d been north, where I’d done some work with the Inuit and my father had been inspired to write Solomon Gursky Was Here.

“Oh?” said Hoffman. “There are Inuits in Canada?”

“Yeah.”

“Hey, sweetheart!” said Hoffman, calling out to his partner, Lisa, who sells beauty salon franchises out of Los Angeles. “This guy spent time with the Inuits!”

Inside, the parlour had been scrubbed. It smelled “of busy days,” said one of the crew, stopping at an arresting poster of an extremely buxom, dark-haired woman in black leather. “No loo,” said the film’s stills photographer, Lantos’s daughter Sabrina, “or at least not one I’m using.” She looked over the crew hand’s shoulder to the poster that had transfixed him. “Very disproportionate,” she said.

A metre or two beyond, Hoffman had moved into position on a narrow massage bed in the back room, which was barely large enough to accommodate the actor and the camera, never mind the director and the crew. Forced to station themselves in the narrow corridor, they were taking turns one by one to step into the space and do their jobs. Check the lighting. Check the lens. Check the talent. Hoffman was enjoying the perversity of it all and, as usual, talking to no one in particular.

“You know what they call an orgasm in France? Un petit mort. A little death. How about that?”

“Only essential crew!” called out Webb, who, one sensed, had long ago stopped listening much to actors. Enough on his plate with the director and the crew.

“I’ve never been in a massage parlour,” said Hoffman.

“That’s what they all say,” said the lighting man.

“No, really. With cameras and the web, you can’t mess around these days. I mean, anything you do is going to end up on YouTube, right?”

Giamatti popped in for a moment to check out the back room into which Barney would be ushered by the madam in the middle of the night and then confront his father’s corpse.

Hoffman looked down at himself. “This does not look like an eighty-year-old body!” he said. Lewis, lean and sinewy, came back into the room for something or other, and Hoffman pointed to him and said, “I used to have your body, and really it’s not so bad, but I want the writer’s body. Did you see those jeans on him?”

We were not far from the old Gayety Theatre, once a vaudeville house, where the stripper Lili St. Cyr used to perform. During the ’40s and ’50s, she was said to be the most famous woman in Montreal. She was something of an icon to my young pa, who was skipping school—Baron Byng, on St. Urbain Street—and playing pool in these parts. There is a synagogue on Bernard, east of Park, its frontage discreet, but the Lubavitcher families still walk the gentrified streets in their Orthodox apparel. The city grows around them and steps out of the way, even as the old Jewish landmarks have become tourist destinations in a borough gaining a new, faux authenticity. The workers at St-Viateur Bagel, where a picture of my father still hangs, are now South Asian, and even the souvlaki joints that staked the claims of a later generation of Greek immigrants are being squeezed out by Middle Eastern grocers and upmarket restaurants. This was my father’s turf, but everything is so prosperous now: superb épiceries, bakeries, boutiques, and bars. But also the Dairy Queen that was the first place my father took me in 1968—me in my pyjamas and fresh off the Empress of Canada, the CP ocean liner that brought the family from Britain for a year to test the waters of his Canadian return. Customs, I remember, set up a table on the ship and gave my father a hard time because my parents had not yet registered the birth of Jacob, less than a year old. “I have four kids already,” said my father to the officer. “You think I want another? You can have him.”

“I can’t stop my breathing,” said Hoffman—and then another hurtle into the past. His stomach, white and revealed, reminded me of my father’s the last time I saw him—dead, and in the same position, but on an ICU table at Montreal General. “I’m not so young anymore,” said Hoffman. “But if my stomach is moving, you can CGI it out, right?”

It had been a long day, the shooting was running late, and other scenes were being rescheduled or cancelled to compensate. But I had stopped paying attention, riveted to the video monitor that, with no room for the tent, had been set up at the foot of the steps to the busy street. Barney was being led into the back room by the madam, who says, “He talked about you all the time. You made him so proud.” Barney sees his father dead on the massage table and starts to weep. Giamatti shook his head, and then it was his turn to improvise a scene for which no words had been written. “You’re a king!” he said, grabbing the inanimate hand of his father-turned-corpse. And then, in a brilliant display of uncontrollable transformation, he laughed to the point of hysteria as the fact of his father’s death and its preposterous circumstances overcame him.

I recognized the moment and was taken aback. It was more than eight years since my father had died, an event for which I had been massively unprepared. They’d sent in a palliative care nurse in that last week of June, though I’d never quite got it—not acknowledged the moment, anyway. After a particularly bad night, when my father had appeared drawn and tired of it all, I’d ventured, “You have to go through with this,” and then, like a suspect trying to play tricks with the needle of a lie detector, slipped in an “I love you, Dad,” along with the requisite “You have to be strong.” “I know,” my father replied tenderly, and I was able to leave the room believing I’d convinced him of the necessity to eat. Who was I kidding? I had a terrible feeling that the next time I walked along the hospital’s drab corridors he’d be dead, and the time after that he was, and in the awful neon light of the ICU his body looked like Hoffman’s, only even more pallid and yellow—unforgettably so.

The first call I made, from the pay phone outside in the hall, was to Jack Rabinovitch. “What do I do?” I asked. “Call Paperman & Sons,” Jack said, using an abrupt, matter-of-fact tone that made me feel idiotic, though I knew that had not been his intent. At Paperman & Sons, my mother was a mess and sat off to the side. Jews, the funeral director explained, believe man is born of dust and returns to it. The dead, he said, are buried in a simple cotton shroud. “However,” he added, “it is also available in linen.”

What a rich lode my father had been mining.

Giamatti did another take, and it made me feel thumped and hollow. The third time, I found it painful. Deaths launch all families in extremis and make their members’ distinguishing aspects more pronounced. Following my father’s death, I’d been the stage manager, a function that had not left much opportunity for weeping.

Giamatti did a fourth take, and I had to turn away. I simply could not watch him go through his hysteria anymore. I fled the steps of the massage parlour and remembered how, months after my father’s death, I’d been sitting at a restaurant with my wife and my best friend, who’d cracked one of his signature punster’s bad jokes:

“Noah, when does a Chinaman go to the dentist?” he asked.

“I dunno, pal. When?”

“Tooth-hurty.”

And then I’d laughed—laughed, like Giamatti, until I’d cried.

Out on the street, Giamatti looked exhausted.

“It worked for me,” I offered.

“Thanks,” he answered.

And then we were at Lake Memphremagog, on land that fell toward Sargents Bay from beneath an extraordinary cottage of the type that used to belong to the Westmount WASPs who had given both French Canadians and Jews a hard time.

Scott Speedman was playing Boogie, the wild best friend and literary role model whom Barney, in the novel, is suspected of murdering. The scene was playing out a little histrionically, the actors not quite settled yet. I took a break from the action to sneak behind the boathouse and, out of view of the camera, go for a swim. When my father had bought our house at the foot of Sargents Bay, he’d dispatched me to a sailing club for the kids of the families on the lake, its shack a couple of bends in the shore away. Nice girls there were, but also conventions. One of the instructors, a Lower Canada College ponce, had taken me aside that first summer to explain one. “You’ve not been coming here for enough summers to be having so much fun yet,” he said—and, amused more than anything else, I realized he actually meant it. To the lake I was not so attached, but I knew what land, Canadian land, meant to my father—from Duddy Kravitz to Solomon Gursky Was Here, and now the clincher scene of this novel, in which a gun goes off and Barney may or may not have shot his closest pal.

From the water, I could see our family’s house, the place where my father had been happiest, and which told him, I imagine, that he’d arrived. It was a cold fall day, but I swam anyway, though uncertainly. I could feel in my bones that I was trying to convince myself of something—and failing. Whose terrain was this anymore? Whose story was being told, and would the production get it right? Did it even matter? At what point does any author’s tale become historical?

Earlier in the day, I’d talked to Sweet Pea, a local jack-of-all-trades and a drinking pal of my father’s. He was in surprisingly good shape—I hadn’t seen him since the funeral—but wistful. The lack of my father was a canyon between us, and I could not get it out of my morbid state of mind that Sweet Pea, too, would probably be dead before I had the chance to visit him again. I asked about Austin and Bolton and the various small communities in this part of the Townships, and he told me that he no longer drank at the Owl’s Nest, the pub on the outskirts of nearby South Bolton where my father used to head at the end of his working day to play the slot machines and grab an hour or two of boozy silence, listening to a few more tales. It was without question the model for the Caboose in Solomon Gursky. Sweet Pea said he now drank at Bar 243, farther down Route 243 toward Mansonville (the spot used to be called Hooters, but changed its name at the request of the popular franchise). I could hear in his voice how much he missed my dad, whose books he’d probably never read even though he’d been so much a part of one.

I decided to take the familiar drive along the 243, past a house that was a rest stop for the mail delivered by pony (the writer John Glassco, author of Memoirs of Montparnasse, was one of those who, during the Second World War, delivered it) to the Owl’s Nest. The old building had been razed and replaced by a spanking new, vinyl-sided one. It was morning, and a bunch of regulars, none of whom I recognized, looked my way warily as I stepped inside and introduced myself to the bartender, a woman who was decidedly unfriendly. I explained my attachment, and she guardedly showed me the framed newspaper clippings about my father that were yellowing in the front hall, an approach to the bar clearly not used by anybody. At the rear, there were now French doors and a veranda that opened out onto a wonderful field and a stretch of river I’d never had any idea was there, as it wouldn’t have been visible from the old Owl’s Nest, which had no windows at the back—just a bar and, behind it, an overgrown patch where trucks were parked. The wall on which my father’s clippings were hung felt like a lonely place, and as I drove away I wished I’d rescued these vestiges of his soul from there.

This part of the Townships, with its beautiful lakes and wooded hills, its twisting back roads and the bootleggers’ paths that had been an inspiration to my father in Gursky and then Barney’s Version, has always been a place of pockets—of stories and communities dropped out of time. Houses are hidden behind roads that run, out of view, between the low mountains, and there are hamlets in which surprising accents still persist. For a moment, we’d thought of burying my father here, changing our minds before my mother shared his written instruction that he be buried on Mount Royal, as by then we’d chosen to do. I looked for Bar 243, but in two sweeps could not find it, instead driving on for the sake of it, and for the comforting pleasure of the long, winding road. I’ve been a lucky son, what with my father’s public life and the many relationships he had and the stories these people have told me since his death. And yet, driving on, I felt the poignancy of a culture, one to which my family happens to belong, passing into the realm of out-of-print books and oral stories that are bound to disappear as the people who speak them do. Writers work hard to avert such a fate, and the rest of us are grateful for their novels, and the films that are occasionally made of them, for the possibility they offer of extending a life, but in our hearts we know better. We understand natural laws. And accept.

This appeared in the October 2010 issue.