Around the start of the pandemic, I would visit a dying woman. As an Anglican priest, I had already seen her several times and spent time with her family. We were always masked at these meetings and often distanced. Then, one night, the call came. She was close to the end, I was told. Would I pray over her on speaker phone and give the last rites?

Anglicans don’t quite call them last rites, and nor do Roman Catholics, really, but I got the point. I agreed and prayed at length. A pause. “She’s gone,” said her daughter. “She’s gone.” Another pause and I could hear someone crying.

The woman’s daughter thanked me; we arranged that I’d visit the next morning. I said I was available at any hour to listen or help and said goodbye. I then realized mine had been the last voice her mother had heard. Did my prayers release her—enable her to let go? Was I, in some way, responsible for her death?

I had a sleepless night of confusing emotions, with guilt refusing to leave the room.

Mine is a late vocation. Six years ago, I began studies for a master’s in divinity. I was made a deacon in 2019, when I was sixty, and a priest in September 2021. Before that, I was known primarily as a radio and television host, a columnist, and author. It was a life I liked. But something was missing. It’s difficult to explain a calling without sounding pious, but as I aged, I began to wonder whether a media career was what I wanted as my legacy. The journey toward ordination was hardly simple. I had doubts, reconsiderations. Surely, I was too old to start over? But faith is like sandpaper on the soul: pain brought growth. What became clear was that there was no alternative. I didn’t want to be a priest; I needed to. To be with people in their pain and suffering. To preach and listen—listen, primarily, to God, who often speaks through the most marginalized and isolated.

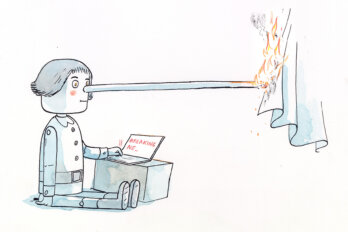

My timing, however, was significant. Photos from the “priesting,” when we are formally promoted to priesthood, show me in full church regalia—with a blue mask over my face. Indeed, most of my ordained life in the Anglican diocese of Niagara has been during COVID-19 and under lockdown. This meant that, for the bulk of those early days, I worked from home. I prayed into a phone instead of from behind an altar. I faced a laptop screen instead of parishioners in pews. It meant conducting services via Zoom, being forbidden to distribute communion, and keeping my distance from people. Rather like being a cleric while wearing boxing gloves.

But I think I managed it. By shutting our doors and imposing strict safety measures, our church reacted to the crisis efficiently and sensitively. The horrors of the pandemic, though, became a testing time for the followers of Christ who preach about loving your neighbours as yourself. COVID-19 created opportunities to think and live communally and to care for the most vulnerable. The church, in its most reductive sense, is a building, and that place was closed. But, in its authentic form, the church is a community, a divine symbiosis of love, a mutual romance based in gospel teachings and modelled on the life of Jesus. And, over the past several years, that version of the church, the genuine church, has been more open than ever.

It didn’t take long for the pandemic to shape the practice of my new ministry in profound ways. My daily tasks as a priest? Lead services at retirement and care homes; meet people who need housing, employment, money, and advice; visit the sick and housebound; help with feeding the hungry. I work as a priest independently (which also means that clergy anecdotes are, by their very nature, personal; there are no witnesses). A constant of all this activity is direct and personal contact. A constant of COVID-19, of course, was the absence of direct and personal contact. How do you counsel, listen to, pray with—and for—people if you can’t share the same space?

In looking for solutions, I was reminded that one of the great predicaments of modern society is loneliness. That’s hardly an original observation, but what might not be so obvious is that churches are magnets for those who, due to crisis or circumstance, find themselves alone. Often, there is simply nowhere else for them to go, and the lockdown made isolation worse. By lonely, I don’t mean only those without family and community but also those who have lost partners. Because they tend to be older, they’ve lost friends as well and watched what was once a thriving group full of joy and conversation shrink by the year.

So I started two prayer groups and a bereavement group and chaired a meeting of parents of adult children with mental health issues. All on Zoom. I also started a telephone support group. Every week, volunteers called to check in with parishioners unable to leave their homes. Our job was to ask after people, be a friendly voice. Since there were certain things I couldn’t do, I had to compensate. You don’t need to embrace someone to show you care. Indeed, hugging is so common as to be drained of meaning. I tried to develop listening skills to reach further than where the usual words and actions could take me. One example remains: a young woman crying at the death of her mother. It was a phone call. I paused. A lot. When you can’t see the person, it’s hard to pace your moments. Instead, you give them plenty of time to complete their weeping, and you stay silent with them in their grief.

Services were a different challenge. At first, we recorded music, readings, and homilies at home and then sent everything to a technical coordinator who assembled it all into a full Sunday worship. Because the Anglican church follows regular liturgy, the various Bible readings are generally set, so that made matters a little easier. When allowed, we recorded all of it in an empty church. Sometimes the live streams worked, sometimes not. Stripped of their traditional setting, my duties felt like an alternative—at times, a substitute for the real thing and, at other times, an admission of defeat. I don’t think I felt ineffectual, but it brought home the realization that while religion isn’t ceremony in itself, it uses ceremony and ritual as a means to an end, which is a relationship with God. I knew that and so did everyone in remote attendance. No matter how we flavoured it or tried to make it palatable, the taste was never quite right.

Then, gradually, small numbers of people were permitted back, masked and distanced. Phone calls were replaced by visits. I drove to the local hospital, where I changed into a gown and mask on top of my white collar and black suit. I was the real thing again, a priest doing his rounds. “Can we talk about Downton Abbey rather than religion?” asked one woman. Sure, I said, I’ve seen every episode. Next, a man in his late eighties asked if we can meet for a chat. “I’ve no complaints,” he said. “I’ve been loved, I’ve loved, I’m fortunate. The bugger is, I don’t think I’ll outlive this lockdown thing.” Of course you will, I insisted. I took his funeral ten days later.

Funerals are unique for a priest. Baptisms and weddings can be fun and social. Not funerals—and certainly not during the pandemic, when sorrow, regret, and memories have been at their most acute. I presided at twelve funerals last year. Sometimes it was just the deceased in the casket and one or two family members. Some of these deaths were COVID related; others not. But all were shaped by the new conditions. No hugs, no physicality. Masking prevents the other person from seeing facial gestures that evince concern and sympathy—I don’t think any of us realized just how vital the lower face is in signalling feeling. Still, a cleric has to sense the mood and act accordingly. This is a job that teaches you as it tests you. You develop an instinct for what to say when holding the hand of a woman who has lost both of her parents to COVID-linked illnesses in the space of ten days and was unable to be with them in their final moments due to medical restrictions. Or how to react to family members furious after being told we can’t hold a service in the building and that numbers at the graveside are limited to ten.

I sometimes meet younger, well-meaning clergy and wonder how they survive such moments. I’m hardly a model for anybody, but I have been married for thirty-five years, have helped raise four children. I’m difficult to shock. And, indeed, the qualities required to be a cleric are not particularly different from those that make a good parent. Give people time, listen to them, take them seriously, be self-aware, be kind and tolerant—and, for God’s sake, have a sense of humour. But there’s something else. Never forget that, for many people, you symbolize something beyond the world and thus beyond their predicament.

Consider this. A woman had just left a care home where she’d visited her husband, whose dementia had so fogged his mind that he no longer recognized his first and only love. She’d had to wave to him through the window during much of the pandemic, but now, after a third vaccine shot and in a more relaxed atmosphere, she was allowed a personal visit. He thought that his wife was his long-deceased mother, but that was okay. Just being in the same room as him was enough. As she walked home, a car stopped and a woman passenger asked for directions. They were gladly given. “Thank you,” said the woman, “and please take this as a gift.” At which point, she rather forcibly hung a thin necklace around the lady’s neck. It was only when she got home that she realized that the woman in the car had removed her original necklace and replaced it with a cheap trinket. The stolen necklace was a gift from her husband. Try listening to the weeping of someone brought low by the darkness of others. But listening is what we’re called to do. Just be there and, if possible, show Jesus, then get out of the way.

But these sessions, with their waves of suffering, stay with you. One day during lockdown, I received a midnight call asking if, in the morning, I’d visit a parishioner who was in very bad shape in the intensive care unit. Of course. Up at 5 a.m., I was at his bed by 6 a.m. With his daughter, we watched the dawn break over Lake Ontario—the juxtaposition of birth and death. When he awoke, this man thanked me for being there and apologized for the trouble he was causing (the latter, by the way, is not uncommon in these situations). Three hours later, I needed to leave. “Phone me if anything happens,” I said to his daughter. “Anything I can do, any time.”

Off to a care home next—tested for COVID at reception, a new mask worn. These places vary enormously. Some are populated by people who are alone now but in a state of comfortable, if sad, retirement. Not that day. I was there to take a service, and from what I could gather, this group—about thirty, all women—lived with dementia. One lady held a baby doll tight; another shook her head in constant disapproval. The group responded a little to the hymns played on an old CD machine. Traditional and tested prayers, I’ve discovered, have resonance. I recited them, thanked everybody, and left. At the door, one of the women, who hadn’t opened her eyes the entire time, said, “Thank you. You’ve made my day. My husband was a priest. I loved him very much.” Then she closed her eyes again. “That’s the first thing she’s said in a week,” a nurse told me. I got into my car and cried. Probably just tiredness.

I pulled myself together, drove off, then received a call that the man I’d sat with earlier in the morning had died. Back to the hospital to say a few words and then speak to his family. I try to explain what I believe about death but never impose, never insist. To do that at such a time risks becoming exploitative. I once knew a cop who left the church because his evangelical partner would try to convert alcoholics living on the street and would be overjoyed when they said that they were “born again.” Meet people in their pain but never take advantage of that pain.

I was back in the car, then the church office called to ask if I could help a young woman who was facing all sorts of challenges. Sure. I called her. Two small children, abusive partner, in an emergency shelter, but it wasn’t right for all sorts of reasons. Because of COVID, it was almost impossible to find anywhere else, and her government support was limited. I made the calls, stayed on the phone for ninety minutes because the lockdown had reduced staff even at emergency centres, but held the line to finally get her what she deserved and was entitled to, which is a safe and decent place to live. I phoned her, gave her the good news, drove her where she needed to be, bought her and the kids some food, and then began my journey home, hoping this was the end of the day. Then I felt guilty because I was supposed to be on call. Priesthood is not a shift but a life. My phone number is there for everybody to use, handed out when you call the church. Middle of the day, middle of the night. Get home, no calls, no emails? I pour myself a glass of single malt.

Another day, another request to visit a woman on her deathbed, this time in a hospice. This was later in the lockdown, and conditions had eased a little. Hospices can surprise people, because they don’t usually look like what we assume they will look like. This one was more like a quiet suburban home. By the bed was a photo of this mother and wife from just a few months ago. So transformed now, so emaciated from the cancer. Death’s propinquity is easy to detect. I know it’s near, can almost feel it. I spoke and prayed, hoping my words would make it through my mask. I wanted her to be at ease and not feel fear. She passed soon afterward.

“Will I ever get over it?” asked her husband, no tears left to shed at this point. I told him that, in my experience, it’s not about getting over death but getting used to it. No use pretending it will be easy. I quoted Christian author C. S. Lewis, which I do quite a lot these days. “The death of a beloved is an amputation.” You’ll find ways to live with it, but the limb doesn’t grow back.

Ilikely deal with more pain, suffering, death, need, and trauma in a week than most people do in a year. It’s what I signed up for. But there’s anger, too, which I’ve also learned to accept as part of the job. Clergy friends in Ireland have been spat at on the street and even physically intimidated after repeated revelations about clergy sexual abuse. I’m often accused on Twitter of being a pedophile. It’s nasty, but given that churches—not just Roman Catholic ones—have been systemically abusive and have then tried to disguise or deny their crimes, I’m in no position to complain. Our reputation is damaged, perhaps irreparably.

Of course, I’ve had my own frustrations with clergy during the pandemic—and here I mean that small but loud number of fundamentalists who campaigned against vaccines. Fairview Baptist Church in Calgary rejected instructions from Alberta’s chief medical officer of health, with the result that hardly any congregants wore masks or stood six feet apart. GraceLife Church in Parkland County, just west of Edmonton, was ordered closed for repeated violations of COVID measures. When six elders of the Trinity Bible Chapel congregation in Waterloo breached lockdown restrictions, the church sent out a press release claiming that they were being prosecuted for “worshipping Christ with our church.”

It was a completely contrived campaign of false martyrdom. Religion wasn’t being persecuted. Churches weren’t under attack. Instead, they were being held up to scrutiny. What was the point in boasting about following a man who strove to alleviate suffering if we did not do our best to make the world safer? If we did not try to find ways to do our work while acknowledging the fact that the virus was dangerous and sometimes deadly?

A brief story might explain. I was at a funeral, and one mourner recognized me from television. He was an anti-vaxer and wanted to share conspiracy theories. There was a time when I would have firmly explained why he was wrong. Now, I sat down with him and spoke about the COVID-related illness and death I’d seen. Not sure he came away convinced, but the experience of seeing so much suffering made me more tolerant, not less.

I also think such moments can help shape perceptions of what I do—help show how all of us are, in essence, an extended family. Most people have little knowledge of churches, with points of contact being weddings and funerals, perhaps a baptism or two. With the pandemic, it sometimes seemed a medical worker or a cleric was the only figure seen by the public. That makes an impression. I remember when, being semiopen for a while and full of seasonal optimism, we were ordered by the head office to cancel Christmas Eve services at the last moment to prevent a new infection outbreak. Five services had been planned—four on Christmas Eve, one on Christmas. All gone.

December 24 is when those who rarely set foot in church make an appearance, because it represents family and celebration. Instead of organizing those services, that night, I visited whomever I could, including a couple I knew well from the church. She was very sick and died just seven weeks later after a prolonged stay in hospital. I think I may have been the last person to give her communion—the wafers that Christians believe represent or become (depending on your doctrinal belief) the body of Jesus Christ.

That visit stands out because, long before I was a Christian, and even longer before I was ordained, Christmas meant family, goodness, and joy. My secular half-Jewish family in Britain celebrated Christmas not as the birth of Jesus but as time for all of us to give, to laugh, to be complete. On that cold, crisp evening, I saw not only the dear suffering woman in front of me but my parents, long gone but increasingly vivid in my memory as I grow older.

There’s an open debate in church circles whether people will return to Sunday services post COVID, whether they’ll rejoin the congregation as we sing together, pray together, and receive the sacraments together. I have a feeling they will. Many need the company of other believers, need the order of organized worship. But online services can’t stop now—as perfunctory as they can be, they allow us to reach too many people, often from outside the country. I recall that one of my sermons, for example, led to messages from Britain, Australia, and central Africa. The most high-profile example of the power of video has been from Britain’s Canterbury Cathedral, where Dean Robert Willis shared morning prayers online. A clip of his cat, Leo, disappearing into his vestments went viral—picked up by media outlets, including CNN, across the world and viewed millions of times online.

Alas, I don’t have a cat. I do, however, have a ministry, and while COVID remains very much a challenge, one of the most welcome aspects of being back inside a church is the ability to stand behind the altar, consecrate the bread and wine, and then administer it. “The body of Christ, given for you,” I say. Then, “the blood of Christ, shed for you.” One elderly lady receives the bread and wine, says her amen, and then touches my hand—squeezes it, really. “Thank you for this,” she whispers. “Thanks for being here, thanks for never leaving.”