Billy Constable hadn’t been sleeping soundly and at four o’clock one June morning he found himself prowling his living room with a cup of coffee clutched in an unsteady hand. His wife, Marva, and their two teenage twins, Troy and Jesse, had gone up to the cottage so there was no one to disturb when he flung open the drapes, switched the CD player on, and set it to repeating one track over and over, Richie Havens singing “Here Comes the Sun” at such ear-splitting volume Billy could almost trick himself into believing the tremor in his right hand was a consequence of the sound waves battering him.

The sun finally did come up, flushed by Richie from below the horizon, a burst of extravagant light that torched a strange, bird-shaped cloud holding fiery wings uplifted. It reminded Billy of the cover of a book assigned in his first-year university English course over thirty years ago. A novel by some famous writer. Stubbornly, he tried to recover the name to forestall thinking about how bad business was. It didn’t work. Worry about Jenkins’s upcoming phone call was swelling a tender blister on his brain.

Business was so shitty that even clueless Marva seemed to sense trouble was pressing in. Why else had she suggested they resign from the Fairview Golf and Country Club? Ordinarily, Billy, who adored golf, would have protested, but feeling he deserved punishment he acquiesced. Besides, the annual dues were steep, so with the club’s approval he sold his membership to Herb Froese, bolstering a cash flow that had dwindled to a feeble trickle.

What Marva hadn’t learned yet was that Billy was looking for a buyer for the cottage. The dock, altar of his wife’s tanning sessions, the sleek powerboat with its triumphal roar, the quaint log cabin, all appeared doomed. Even the house he stood in now, his gut slumping forlornly over the waistband of his jockey shorts, was in jeopardy.

He needed a nicotine jolt. That was something else Marva didn’t know, that hubby was back on the booze and cigarettes. Two years ago Billy had awakened to an elephant squatting on his chest, a crushing coronary. In the hospital, a teary Marva had begged him to mend his ways and, contritely, he promised he would. But in the last desperate months he had turned into a sneaky, slinking backslider.

Billy killed the music, put on his tartan housecoat, collected a pack of du Mauriers he had cached in the glove compartment of the Lexus and circled around behind the house. Only by keeping to the great outdoors could he prevent Marva from sniffing out the stale stench of his fall from grace. There the towering blue spruces shielded him from the prying eyes of any early-rising neighbour. Lately Billy sensed friends and acquaintances were checking him for signs of failure and finding them.

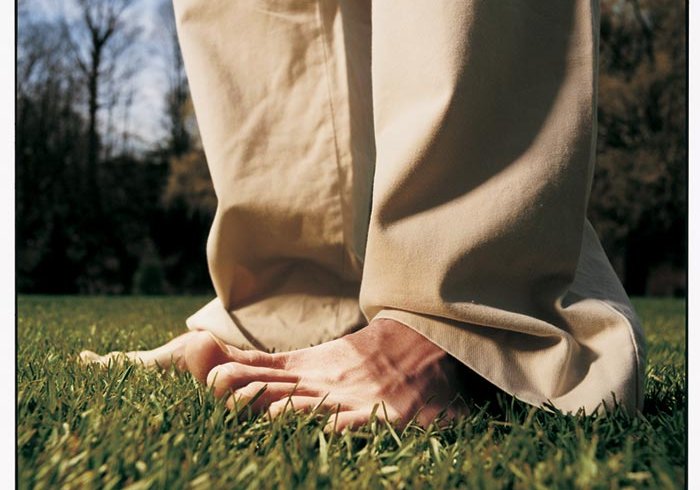

He lit up, greedily tugging smoke into his lungs as he roamed the property. He was a big man of fifty-three with the fleshy, corroded body of the former athlete, but his bare feet still moved with nimble assurance through the dew-drenched grass. Sunshine was strafing the backyard. The evergreens flung spiny swatches of black shadow across the lawn. A mob of sparrows scattered from the birdbath at his approach, flecking the blank blue sky with their panicked flight. The jay in the neighbour’s tree jeered at him, mocking his disgrace.

Still, Billy began to take heart. After all, summer was his element, a season as hot-blooded, aggressive, and optimistic as he had always been. Summer fit his nature like a glove. Things were going to be all right. He would survive this. Jenkins had promised to phone by five p.m., and whatever else might be said about the flinty-hearted prick, he was a man of his word. If Billy could land the contract to install plumbing in the condos Jenkins was building, the bank could be held at bay. With mortgage rates at an all-time low, construction was booming and there was more work to nab. He just had to think positive, correct past errors of judgment, and everything would be fine. The trouble was waiting for the goddamn phone call. Jenkins was certain to keep him hanging by his fingernails until the last second. A power trip, as Billy used to say in the misty, faraway days of the sixties. But, he told himself, maybe this was all to the good. Maybe this situation was a lesson for him, a reminder of where impatience and recklessness could land you. Hugging this comforting thought close, he headed back to the house.

At seven-thirty the phone rang and Billy’s unstable ticker gave an anxious lurch. It couldn’t be Jenkins, not at this hour. Had the boys flipped the powerboat? Wrapped Marva’s Volvo around a power pole? To his relief it was Herb Froese calling, the man who had relieved him of his membership in Fairview. Herb apologized for the early-morning call, explaining he had a tee time for 12:30, but one of the original foursome had ducked out. Did Billy want to play? As his guest, he added tactfully. At first Billy was inclined to refuse outright, feeling this invitation to his old haunt was meant to humiliate him, but as he listened to Froese ramble on, he relaxed. Herb was a hacker so apologetic about his game that playing with strangers gave him fits. On a busy Sunday, there was a chance some hopeful single might attach to the threesome and Froese would run the risk of an afternoon spoiled by scarcely veiled condescension. Once Billy understood he was being asked to do Herb a favour, he graciously accepted. At least now he had something to occupy his mind until five o’clock. Maybe his luck was turning.

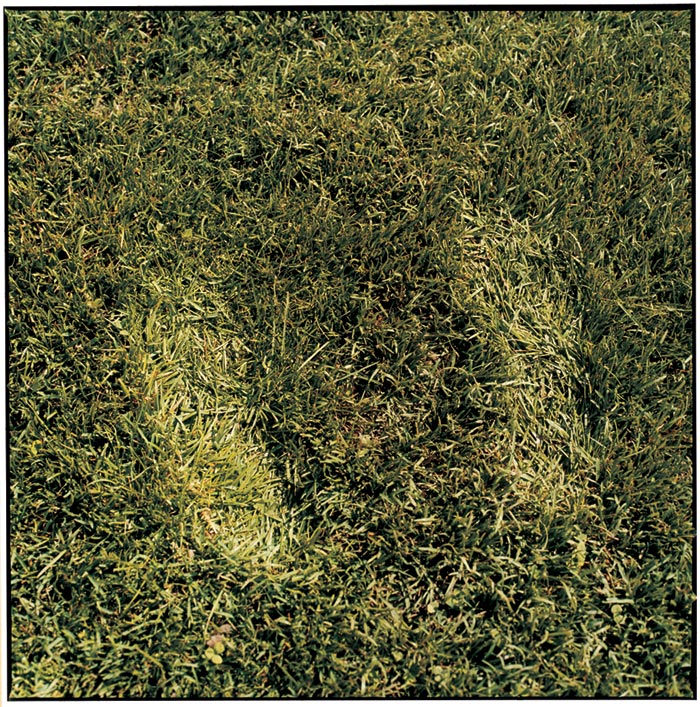

Billy arrived at Fairview early. So far this year he had only squeezed in three rounds on public courses; his game was rusty and hitting a bucket of balls would work the kinks out. As he toted his bag towards the driving range he felt his heart soar. It was a beautiful, warm, brilliant day. Fairview looked in great shape; add a flock of woolly lambs to all that rich green pasture and it would be a shepherd’s wet dream. Suddenly Billy halted dead in his tracks. Malcolm Forsythe was on the driving range, “working on his game.” The evil little turd was always spouting hackneyed golfing clichés that sent Billy around the bend. “Keep it in the short grass,” “It’s not how you drive, it’s how you arrive,” “I don’t have my A-game today.” Everything about the man irked him. That abbreviated, granny backswing mechanically dinking out balls straight as a plumb line, that stupid tweed cap Forsythe had brought back from a trip to St. Andrews sitting on his head like a weathered cow pie.

Billy had a bigger grievance against him. He blamed Malcolm for making him buy the Lexus he couldn’t afford. Billy hadn’t intended to go high-end, but Forsythe’s smirking assumption that he couldn’t afford a luxury automobile had forced him into an impulsive leap over the brink. What’s more, to avoid Forsythe running a credit check, he had liquidated his measly fund of RRSPs so he could pay cash.

The very sight of Forsythe sent Billy fleeing for the clubhouse. There he received awful news from Herb Froese and his buddy Skip Jacobs. Forsythe would be playing with them today.

As usual, Forsythe rudely kept them all waiting until seconds before their start time. Billy piled onto Herb’s cart, making sure he wouldn’t have to ride with the horse’s patoot. On the first tee box, Forsythe said, “So, boys, who wants to lay some loose change and make this interesting? ” Forsythe, a seven-handicapper, was always trying to milk somebody who was half the player he was. Herb Froese had paid for Malcolm’s after-round drinks so many times, he flatly refused, and Skip frugally followed suit. Forsythe turned to Billy. “It’s just you and me, sport. Mano a mano? Stroke or match play? ”

Billy took his time lighting a cigarette. “Match play is chicken shit. Let’s play skins. Carry money forward if we tie a hole.”

“How much? ”

“Hundred a hole.” The look on Malcolm’s face, the awed silence that fell on Skip and Herb delighted Billy.

“Jesus,” said Forsythe. “So much for a friendly outing.”

“Money talks, bullshit walks,” said Billy, flamboyantly yanking his driver from the bag. He could sense the shrewd cogs turning in Forsythe’s mind. Reluctantly, Malcolm nodded. Billy had backed him into a corner, just as he had been backed into one over the Lexus.

Billy, a big hitter, always found the first hole, a 545-yard par five, extremely tasty. As he addressed the ball with his Big Bertha he heard Forsythe snidely remark, “That driver looks like a toaster on a stick.”

Billy lifted his head. “It’s legal.”

“I didn’t say it wasn’t.”

The exchange gave Billy pause. “Course management” was one of Forsythe’s mantras. Play it safe, weigh risk and gain like a bean counter. If Billy pulled the ball left, with his distance he was out of bounds. The story of his life. Five hours ago, he had been telling himself to correct his mistakes; trading the driver for a three iron, he split the fairway. Forsythe went with a driver but as their carts rolled down the fairway Billy noted Malcolm had gained less than ten yards on him. This old dog can learn new tricks, he thought gleefully. His cautious new attitude paid dividends for two holes; he stayed even with Forsythe. But on the third, Billy shamefully four-putted. For him, putting was like a visit to the dentist; he just wanted to get the pain over with as quickly as possible. The double bogey cost him a hundred bucks.

With all the Sunday traffic the next hole, a par three, had backed up. There were two foursomes ahead of them on the tee, giving him time to regroup. Also, sexy Joanne arrived on her refreshment cart. Nobody else wanted anything, they were keeping a Presbyterian Sunday, but Billy sauntered over.

“Where you been, Mr. C? Haven’t seen you in ages.” Joanne always called him that; Billy was a great favourite of hers. Knowing she was a single mother, he had always tipped her outlandishly and made a point of asking after her little boy.

“I guess you didn’t hear. I quit the club. Too much business on the go. No time for golf …” He faltered. “Except now and then.”

“That’s a crime. Otherwise, how are things? ”

“I’m down a hundred to Forsythe. They could be better.”

“He’s so tight he squeaks when he walks. Just get up on him, he’ll choke.” She seized her throat, crossed her eyes, and mimed Forsythe’s strangulation. Billy laughed until his eyes ran. She was a great girl, even if she was what Marva called a “trailer tramp.” Billy happened to like saucy trailer tramps. They were the reason that he had always volunteered to take the twins to the Exhibition when they were kids. Marva accused him of lusting after corn dogs but it was the young women in high heels and ankle bracelets, little crescents of jiggly white bottoms peeking out from under cut-off blue jeans, that drew him to the midway. Boner city.

“What can I do you for? ” asked Joanne.

“I’ll take two beers. Any brand, whatever’s coldest.”

During the time he stood chatting with Joanne, Billy drained one beer and got another under way. When she hinted it was time for her to go, he fumbled out his wallet and pressed a twenty on her.

“Hey, Mr. C., that’s mighty big of you.”

“So you don’t forget me,” Billy said. “Keep them coming.”

“I’ll catch you at the turn.” With a cheeky wink she sped off, the contents of her cart rattling merrily.

Billy hadn’t eaten breakfast or lunch; his guts were too twisted up over Jenkins’s phone call. On an empty stomach, the beer gave him a mild buzz. His arms felt boneless and loopy as he prepared to hit to the fourth, a green surrounded with water blinking hot light like a pinball machine. Normally, fear of sending his ball into the drink would have tensed Billy up, but the beer was smoothing the wrinkles out of him and he took an easy, relaxed swing. The ball landed with a feathery hop, settling four feet from the hole. Miraculously, Billy overcame his yips, made the birdie putt, and pulled even with Forsythe.

This mellow, comfortable feeling carried over to the next hole and he won it too. Joanne was right. Seeing Billy’s taillights, Forsythe started to whine and moan about bad breaks; his forearms bunched up into knots when he gripped his club. By the time they made the turn to the tenth, the King of the Car Dealers was two hundred down.

Glancing at his watch, Billy was surprised to see it was already three o’clock. The course was congested but he hadn’t realized they were moving so slow. Now he wondered if he’d make it home in time to catch Jenkins’s phone call. Feeling uneasy, he considered packing it in, walking back to his car. Forsythe would certainly be happy to see him go and save two hundred bucks. That was enough for Billy to shake off the idea. After all, who did Jenkins think he was, expecting him to sit by the phone all day? And besides, here was Joanne waiting for him just as promised, parked in the shade of a stand of poplar, flashing a big toothy grin. Taking care of him.

“Well? ” she said.

“You were right. He’s wilting. I’ve got him by the short and curlies.”

“Good for you. Two more? ”

“You read me like an open book.”

As Joanne dug down to the bottom of the cooler searching for the frostiest beers, Billy studied the crowns of the poplars. They ran with a liquid ripple in the faint breeze, streamed like a green brook. All at once his heart and eyes overflowed with the loveliness of it. He thought of his father, his grey harassed face. A journeyman plumber, Richard Constable had made the daring leap into establishing his own business, a mom-and-pop affair where he was the only worker and his wife kept accounts on the kitchen table. Slowly, conscientiously, Billy’s father had nurtured the business, step by careful step, until forty years later it had become a prosperous, moderately sized concern. As long as the old man was alive he’d kept a sharp eye on the workers, the bottom line, and above all Billy. But when he died seven years ago, Billy had seized the chance to turn Constable Plumbing into something truly impressive. He had calculated that in twenty years he could get himself and his family to where they deserved to be, enjoying the good life his Pop had been too timid to claim. What had the old man ever done but work? He had died in the boxy bungalow Billy was raised in and Billy’s mother had done the same less than a year later. When had his Pop ever savoured a day like this, the world his oyster, a pretty young woman waiting on him hand and foot? Live large, or don’t live at all, Billy thought.

His reverie was interrupted. “You okay, Mr. C? ” Joanne was holding out his beers, a look of concern on her face.

Billy wiped his eyes with the back of his hand. “Goddamn allergies,” he said. “June is always bad.” To cover his embarrassment he downed a bottle.

“Whip Forsythe’s ass, Mr. C.”

“Consider it whipped,” said Billy.

But Forsythe was far from whipped. He kept grinding away, relying on his short game for salvation. Every time Billy was sure he had him on the ropes, Forsythe scrambled back with a crisp wedge, a deadly chip, a seeing-eye putt. Neither of them managed to win a hole outright; the pot steadily increased and as it did Forsythe’s play grew more and more deliberate. He pondered each shot for an eternity, studied putts from every angle, endlessly stalked the green. It was like watching paint dry. Agonizingly the minutes ticked by, marching towards five o’clock as Billy checked and rechecked his watch. On the fifteenth green, he leaned over and muttered to Herb, “Hello? The weekend will be over in just nine hours. What the hell’s he up to? ”

“Why,” said Herb with that sweet innocence Billy found so endearing, “that putt is worth six hundred bucks. Don’t tell me you lost track? ”

As a matter of fact, Billy had. He knew it was big money but not down to the precise dollar. It was how he always operated, guesstimates, ballpark figures. Worry about being late for Jenkins’s call had ruined his concentration, which was haphazard at best. Gritting his teeth, he said, “No way he’ll make that. No way.”

But Forsythe did make it, a downhill, snaky, twenty-five footer. Snatching his ball from the hole with a flourish he strode past Billy chirping, “Drive for show, putt for dough.”

The standoff continued until the eighteenth, nine hundred bucks at stake on the final hole. Billy had belted down his two beers and found another one lodged under the seat of Froese’s cart, God alone knew how long it had been there. It was warm as piss but he swigged it greedily, Herb watching him sidelong, eyebrows disapprovingly arched. All that brew was catching up with Billy but luckily a toilet was situated nearby and he trotted over to ease his brimming bladder. When he flicked the light switch in the privy nothing happened, some electrical malfunction, or the bulb had burned out. So Billy left the door open, fishing his unit out just as two carts bounced up, one with women on it. Startled, he kicked the door shut and was cast into utter darkness except for the wan glow of his wristwatch. Looking down he read 5:05.

The heat stored in the still, confined space seemed to swell, popping sweat out all over his body. He felt dizzy and short of breath, had to brace himself on one arm above the urinal. An ominous red light was blinking in the swarming blackness, a trick of his light-deprived eyes. It rooted him to the spot while a cruel, indifferent hand squeezed his heart in time with its pulse. “Fuck,” he said. “Oh fuck.”

When Billy reached the tee box, everybody was annoyed with him. Forsythe said, “We got tired of waiting for you. We’ve all hit.”

“I needed to siphon the python.”

“Little wonder, the way you’ve been knocking back the beer.”

“It’s a great game, golf,” replied Billy. “The one sport where you can drink and smoke as you exercise.” He lit his last cigarette, crumpled the package, and tossed it in the trash. “Just for interest sake, you didn’t happen to hit it in the bush did you, Maestro Malcolm? ”

With a smug smile, Forsythe an-nounced, “Dead solid perfect, just past the dogleg.”

“The plot thickens.” Billy sat down on Herb’s cart and began removing his golf shoes and socks. Skip Jacobs, who hadn’t said a word to him all afternoon, irritably squawked, “What now? You got a stone in your shoe? ”

Billy didn’t answer, simply strolled to the tee box in his bare feet, coolly swishing his driver back and forth in one hand.

“Showboat,” said Forsythe. His voice was nasty, contemptuous.

Right now, there was nothing the King of the Car Dealers could say to Billy that could touch him. “Sam Snead used to say when he needed to find his swing, he’d hit balls in his bare feet. He wanted that connection with the earth. Me too,” he calmly said.

“Shit.”

Billy was remembering when the twins were small and just learning to walk, how he had pulled off their shoes and socks, and put them down on the newly sodded lawn of their first house. He and Marva had roared with laughter as the boys capered about in a high-stepping chicken gait, squealing with delight as the soft shoots of grass tickled the soles of their feet. Billy looked down at his own feet, the thick, yellow nails of his big toes. He wiggled them ecstatically and peered down the long channel of fairway bounded by trees on each side, to the right a peninsula of spruce pinching it even tighter at the two-hundred-yard mark.

Toughest hole on the course and Billy Constable was going to bring it to its knees by hitting a high cut that would turn the corner of the dogleg. If he couldn’t shape it, if the ball didn’t curve, it would all be over. Billy smiled, waggled the head of the driver, and took a mighty slash.

The ball soared upward like a jet rising from a tarmac in a steep, accelerating climb. Billy leaned forward, held his breath, saw it bank right on cue, a gradual swoop to the right, all systems go, the pilot firmly at the controls as it curled around the trees. A shot of a lifetime.

Forsythe looked like somebody had given his nuts an unfriendly squeeze. “Horseshit luck,” he said in a choked voice.

“Drive for dough, putt for show.” Billy took the pitching wedge from the bag. He had played Fairview so often he knew exactly where his ball would lie. Striking the down slope of the fairway it would run hot, maybe as much as three hundred yards. Without hesitation he started off walking. Moments later he heard the whine of an electric motor. Herb pulled alongside. “Hey, Billy,” he said, “hell of a shot. Jump on.”

Billy shook his head. “I’m walking this one.”

“You don’t look so hot,” said Herb. “You look awful pale. You all right? ”

Billy waved him on. “Couldn’t be better,” he said and Herb left him, looking back over his shoulder with a perplexed expression on his face.

Billy didn’t need to see Forsythe frenziedly thrashing the ground with his club after he duffed his second shot to know he had the money clinched. He had known it was a done deal on the tee box, just as he had known the other deal was done as he leaned against the wall of the hot, reeking toilet. With that tiny red light winking malignly at him, it came to him that it wasn’t his creaky thumper that was crashing on him; it was his delusions.

The message waiting for him on his answering machine would not be good news. Far from it.

For weeks he had been ducking the obvious truth. Sure Jenkins had politely listened to his sales pitches, but only out of pity. Even that famously hard-hearted bastard hadn’t been able to bring himself to murder Billy’s hope. At least not face to face with the victim. He had provided Jenkins with an easy out. A short, quick knife thrust, a dry, matter-of-fact voice on a scrap of tape.

Billy paused and looked around him. An aeration fountain on a nearby pond was fluttering a rainbow-coloured fan in the sunshine. Massive billows of cumulus rode above the clubhouse. On the terrace, blue and white parasols beckoned with the promise of shade and ice-cold beer. His mind opened, and he saw again the bird-like cloud on this morning’s horizon when everything seemed salvageable. The word for it was phoenix. The emblem of that English writer with sex on the brain. The professor had said it was mythical, an imaginary bird that rose from its own ashes. The only bit of information that ever claimed Billy’s attention in the entire boring class. Well, he was toast now. Burned to a crisp and nothing left for his creditors to do but sift through the blackened crumbs of him. There was no rising from these ashes. Not with overdue goods and services taxes owing to the government, unpaid suppliers, bills and more bills.

He started for his ball, tramping right through a fairway bunker, a terrible breach of etiquette, but he was never coming back to Fairview anyway. The powdery white sand seared his feet and then he felt the lush, cool grass caress and soothe his soles. The contrast was wonderful. Just like sweet and sour ribs, his favourite Chinese food.

It was only June, but Billy Constable figured he had less than twenty more minutes of summer left to him. He intended to make the most of it.