Before the pandemic, my son didn’t get much screen time. We didn’t own a television, and long days of school and work meant that dinner, homework, and bath time ate up most of our evenings. On weekend mornings, he would watch cartoons on the family iPad. I wasn’t zealously against screen time, but I did feel a vague smugness over how little my son got.

Then the first COVID-19 lockdown started midway through his third-grade year, and like for many kids, the hours he spent in front of a screen—both for school and for fun—increased dramatically. Under any other circumstances, I would have been eaten up with guilt. I’d read plenty of warnings about the dangers of screen time that correlated it with everything from sleep disturbances to aggressive behaviour to delays with communication and problem solving. But my brain was too consumed with just trying to make it through the day with my sanity intact.

My sister was the one who suggested getting my son a Nintendo Switch gaming console to help cope with lockdown boredom. My son was eager to play Animal Crossing—a video game where the user builds a house and interacts with their new neighbours—but encountered an early stumbling block. His formal education up until then had all been in French, and his English literacy skills weren’t strong enough to keep up with the text-heavy game. Still, he persevered, and a few months later, he read his first English novel.

Hang on, I thought. Did a video game just teach my kid how to read?

Concerns about children and screen time are nothing new. When I was growing up in the 1980s and ’90s, my mother would shoo me outdoors while quoting a cautionary Shel Silverstein poem about a boy who turned into a television set (because he watched too much television, naturally). Of course, that was back when none of us carried tiny supercomputers around in our pockets.

Today, the Canadian Paediatric Society recommends no screen time for children under the age of two, citing studies that show a correlation between exposure to screens—even televisions playing in the background—and preschool language delays. They also cite studies that show a link between screen time for children younger than five years and negative impacts on attention, working memory, and impulse control. Up until recently, the society’s recommendation for children between the ages of two and five was no more than an hour of screen time a day.

When my son was a baby, I took those recommendations to heart. I watched television while he nursed as a newborn, and I remember worrying about him glancing at the screen, as if just a few seconds of TLC’s Cake Boss would shape his brain forever. As he got older and I spent more time with other mothers, nearly all of them admitted—some with shame, others with defiance—that their babies and toddlers got screen time. These days, parents of kids of all ages seem more conflicted than ever. Instagram and TikTok are inundated with content creators touting the benefits of their “no screen households” and sharing their device-free bedtime routines (never mind the irony of using social media to brag about how little you use devices). Offline, my friends and I share tips and tricks on how to put our kids on a “screen-time diet.”

But maybe some of our anxieties are misplaced. Kristyn Sommer, an Australian academic specializing in early cognitive development, who also runs a popular TikTok account, says many of the studies on children and screen time are outdated. In an episode of the podcast Mama Matters, she mentions that older studies show something termed the “video deficit effect”—namely, that children don’t learn as well from screens as they do from other humans. But Sommer says this deficit is lessening over time—which she theorizes might be because of technology becoming more “enmeshed” in society.

Sommer also says one major parental concern about screen time is the behaviours it seems to elicit in toddlers and preschoolers: the whining, tantruming, and general perseverating that can happen when they don’t get TV or tablet time when they want it. But, notes Sommers, these behaviours can be mitigated by having set routines and limits around screen time.

But what about as kids get older? One Canadian study that followed a little over 3,800 adolescents for six years suggests that not all screen time is created equal. The study looked at the impacts of social media, television, and video games on adolescent moods and found that the first two correlated with depressive symptoms in the subjects. Unsurprisingly, social media seemed to have a particularly negative effect on teen self-esteem.

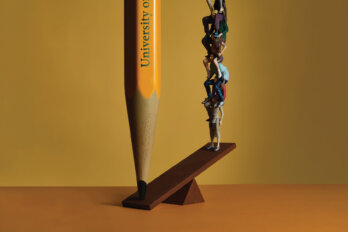

“One thing that’s unique about social media is that it’s peer-generated content,” says the University of Montreal’s Patricia Conrod, a clinical psychologist and one of the study’s authors. “The second thing is that the content that you observe tends to influence the kind of content you’ll be then exposed to again. And so we tested that further by identifying whether there was any association between someone’s current depression levels and the likelihood that their social media will further influence their depression, and we did find evidence of this kind of reinforcing spiral.”

Conrod and her co-authors aren’t the only ones sounding the alarm bells when it comes to social media. Recently, Vivek H. Murthy, the US surgeon general, called for warning labels on social media platforms, citing them as an “important contributor” to the mental health crisis faced by America’s teens. In an interview with the New York Times, research psychologist Jean Twenge said she had just one thought when she heard the news: “Finally.” While it’s obviously harder for parents to control what tweens and teens, compared to younger children, have access to, Twenge does have some suggestions on how to curtail time spent on social media: her top piece of advice is to get phones out of bedrooms at night and charge them in a communal spot. Another piece of advice is that parents should be modelling the behaviour they expect from their kids.

Every parent-to-be has a personal set of rules they’re sure they’ll stick to. No screen time before the age of two, no sugar before the age of one, no processed foods or plastic toys. But most of us inevitably end up breaking, or at least bending, them. It’s hard to envision the reality of parenting babies and small children until you’re actually in the trenches. It doesn’t help that life sometimes throws some curveballs, like a global pandemic.

For many parents and researchers, the question of how kids learn from screens grows ever more pressing not just because screens are everywhere but also because so many of us had to grapple with online learning during the COVID lockdowns. Even in a post-lockdown life, it’s a question that’s not going away. When students are absent, they’re often expected to make up the work through an online portal, and high school students in Ontario are required to have two e-learning credits in order to graduate. Kids of all ages are learning from screens. Parents need less guilt and more support figuring out the what and how of screens: which devices and types of content can be enriching, which are necessary, and how to navigate social media.

To its credit, the Canadian Paediatric Society recently changed some of its guidelines. Instead of worrying about the quantity of screen time that preschoolers engage in, the new guidelines suggest, parents should consider the quality of it. Preference should be given to activities like interactive educational programs or family movie nights over solo passive viewing of, say, cartoons on a tablet.

My son gets a lot of screen time these days, and it’s hard not to worry about how that’s affecting him. He’s in grade seven now, meaning that much of his homework is done on a computer. He still loves video games and has recently developed a love for YouTube videos about Lego. I try to remind myself that screens form a major part of the world we live in, whether I like it or not. The most I can do is to help my son build healthy habits around them and recognize that, even with my best efforts, he won’t always succeed. I certainly don’t—just ask my phone.