Listen to an audio version of this story

One of the most memorable scenes from Kate Beaton’s new graphic memoir happens at a routine safety meeting. It’s April 2008, and Beaton has been working in the Alberta oil sands for over a year. She is far from home, as are most of her co-workers; people have come to the mines from across Canada and beyond its borders.

“Okay boys—couple notices here,” the man leading the meeting says. He rattles off a warning about appropriate PPE. Then, the staff learn that one of their peers has died. The worker suffered a heart attack and threw himself out of a crane to avoid accidentally landing on the controls and hurting those around it. But the death feels like a footnote at the gathering, and despite a few murmurs, it is shrugged off by those present. The staff are more preoccupied with a group of ducks that got stuck in nearby tailings ponds—the toxic sludge that results from the oil-extraction process—and the steps they need to take to avoid it happening at their facility. The birds certainly garner more attention from the public: the New York Times covers the story, and by the end of that year, more than a thousand ducks perish at the nearby pond.

Not long after the safety meeting, another man dies while driving on a notoriously dangerous stretch of highway linking the oil sands north of Fort McMurray. News reports misidentify him as a “Calgary man,” but Beaton recognizes his name as one from down home. She immediately knows the papers are wrong: the man was from Cape Breton Island, as is she.

“It’s like I know him. I could be him,” she tells a co-worker while poring over a CBC article. “That headline bothers me. They can’t have him. He’s not Calgary’s. You know?”

In Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands, Beaton includes these tragedies to highlight an often-ignored part of Alberta’s oil industry: the lived experiences of its workers. The memoir is a departure for Beaton, the celebrated cartoonist known for the whip-smart humour of her series Hark! A Vagrant, which she began to draw during her off-hours in the province.

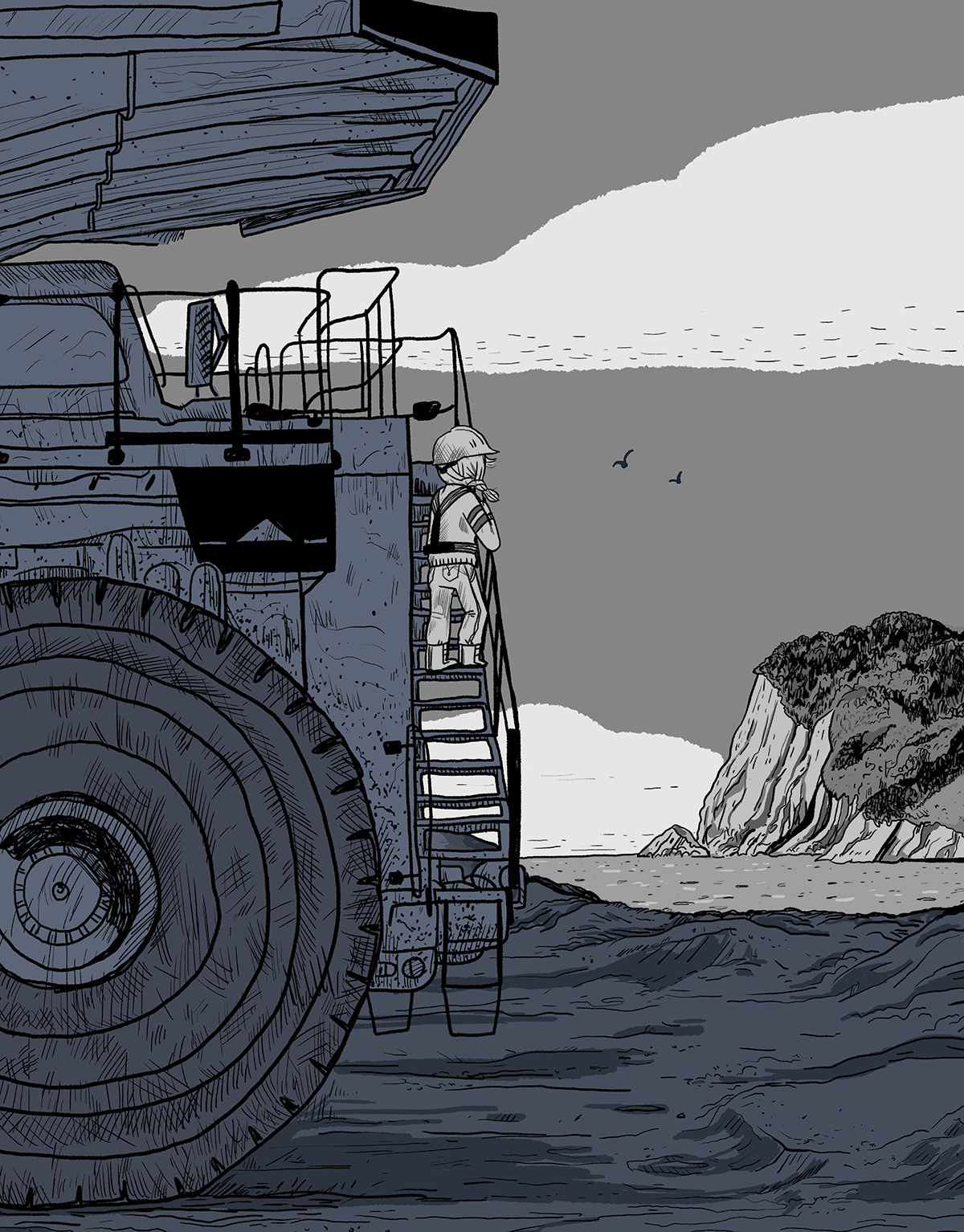

In her latest book, she writes about her time with some of the world’s largest oil companies. Though environmental impact is a big part of the story, the unspoken personal cost of this kind of labour is at its heart, with Beaton drawing parallels between the destruction of the land and its workers. Using stark, sprawling illustrations and casual dialogue, she reflects—as one of very few women in work sites dominated by men—on the loneliness, trauma, and sometimes violence that can accompany making a living.

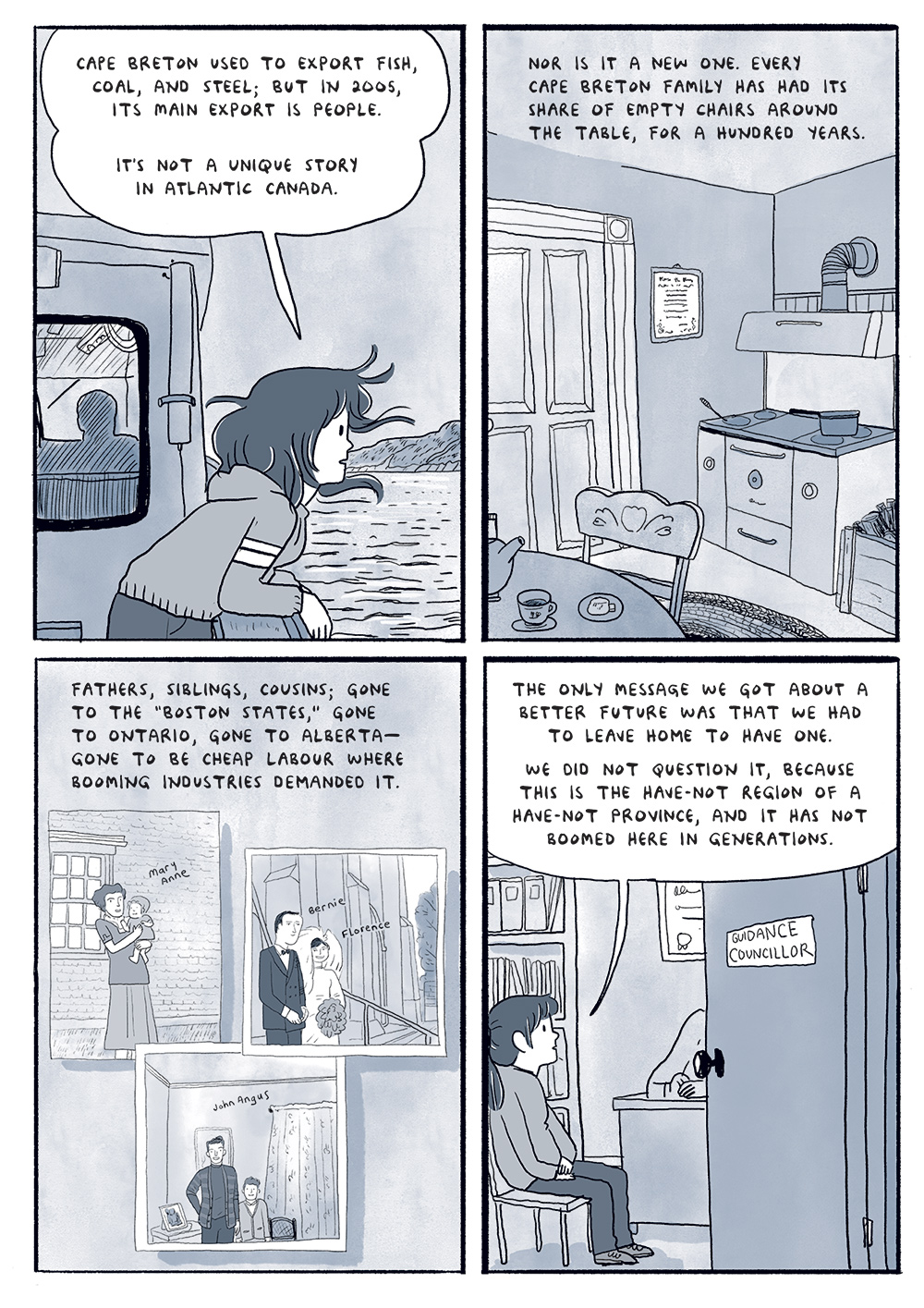

The book opens in 2005, when Beaton is twenty-one years old and freshly graduated with a bachelor of arts, paid for with student loans, from Mount Allison University in New Brunswick. After university, she lived with her family in Cape Breton, the Nova Scotia island known for its wild landscape and sweeping coastal views. Cape Breton has been home for the Beatons for generations, and it is hard for her to imagine leaving. But, for Kate, it doesn’t feel like a choice. The island is recognized for its natural beauty, but it’s also known to be a place with few work opportunities—a place whose people must often depart in order to survive.

As Beaton writes, the necessity to travel is ingrained in her hometown’s culture. Cape Bretoners are constantly faced with two opposing feelings: “a deep love for home, and the knowledge of how frequently we have to leave it to find work somewhere else. This push and pull defines us.” The universality of this experience doesn’t make it easier. Beaton understands she needs to leave Nova Scotia to escape crushing student loans, no matter how badly she wants to stay with her family.

“I’ll be back before you know it,” she tells her mom before boarding a flight to Fort McMurray. However, at the time, Beaton doesn’t realize the extent to which her time out west will change her.

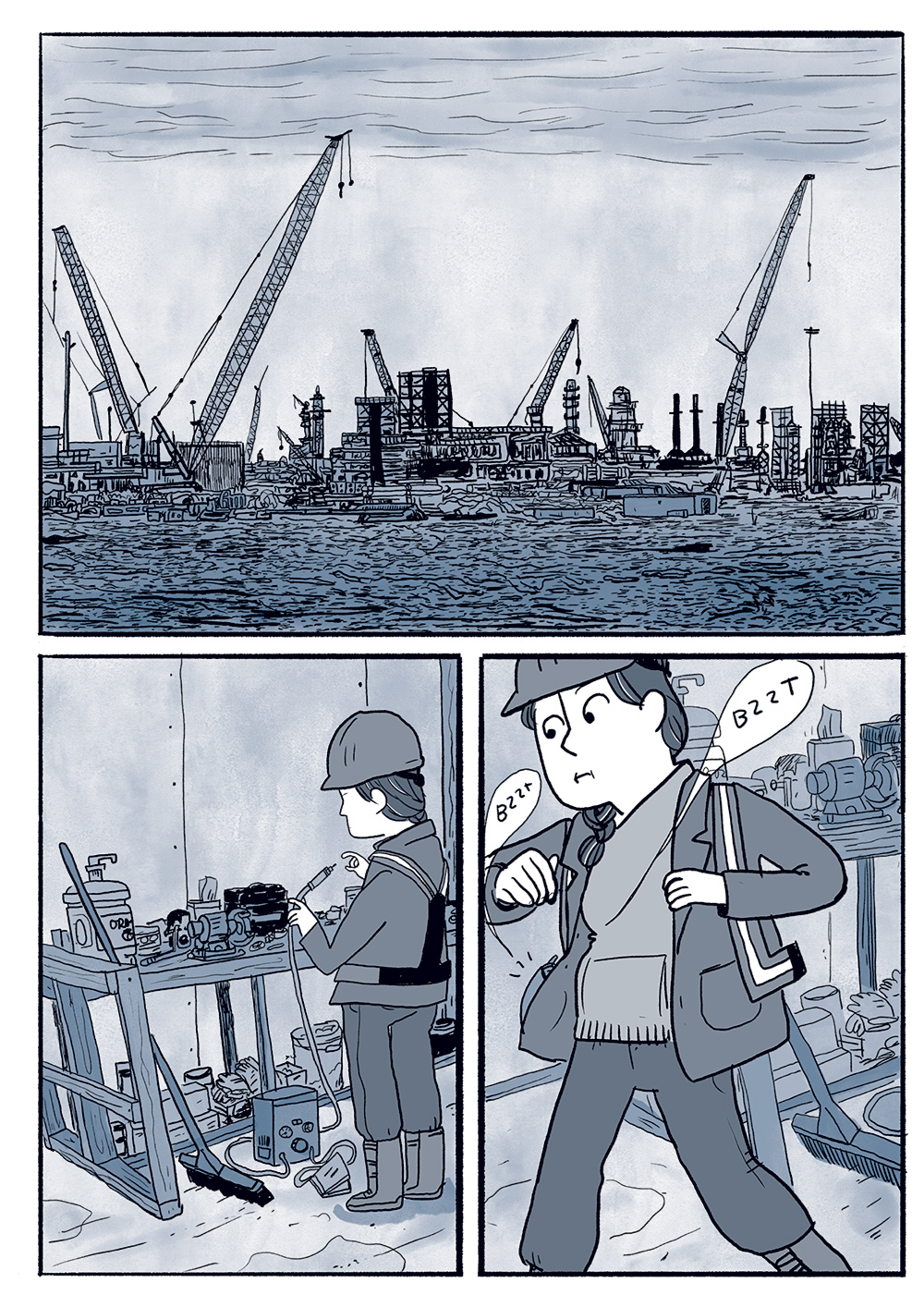

After she arrives in Fort McMurray, Beaton finds an apartment and two jobs: one at a restaurant, the other at a tool crib for an oil refinery forty kilometres north of the city. The work involves keeping an inventory of tools and handing them out to workers, and the hours are long—six days on, six days off, with twelve-hour shifts daily.

Beaton is overwhelmed by the sheer scale of the oil sands, which she shows through illustrations of heavy machinery, expansive work sites, and deep, dark skies. And yet, some things are comforting and familiar: everywhere she turns, she meets people from down home—the sound of an East Coast accent is always within earshot.

This is the first of many sites Beaton works at during her time on the oil sands, but they all share certain similarities: feelings of loneliness, the presence of people who are far from home, relentless work hours. One of these similarities is particularly striking. As she moves between workplaces, she experiences continued, often subtle, harassment and misogyny from her peers. Droves of male co-workers—she estimates the ratio of men to women is fifty to one—leer at her throughout the day. They line up around the tool crib to make comments about her body. They call her by pet names; they spread rumours about who she is sleeping with; they corner her alone.

Throughout the book, dealing with this kind of treatment is a compromise Beaton constantly has to make to earn her living. The abuse she faces is a harsh reminder that while there is near-constant public discourse around the need for jobs on the oil sands, there is rarely ever discussion around protections for the women and minorities who labour in these remote places.

Beaton eventually moves to a work camp for higher pay. There, she lives on site instead of commuting every day. With home and work combined, everything about the oil sands—the isolation, violence, longing—feels amplified.

As the memoir unfolds, Beaton at once grapples with two things. The first is her role in environmental destruction. She learns about how the oil sands are destroying the earth around them—in particular, how difficult they’re making life for the Indigenous people who live in the area. “First Nation people’s lives pay for the price of the oil they take out of our land here,” says Celina Harpe, an Elder from the nearby Fort McKay First Nation, in a video Beaton watches with a co-worker. In the years that follow, the pollution from the sands is shown to increase the risk of cancer in nearby First Nations.

“This is us, too,” Beaton says to a colleague. “We’re not the president of Shell, but we’re here.”

Beaton also reckons with what the camps’ labour conditions do to the people who work and live there. There are, of course, physical risks. People get injured or die at work and worry about falling sick in the future. More often ignored are the mental impacts. As she watches her co-workers be cruel to one another and as she experiences this cruelty herself, she wonders about the emotional toll of being at the oil sands—whether being there is changing the residents irreparably.

“Do you think people are different here than they are at home?” she asks a co-worker.

“’Course they are,” he says. “This is a rat cage.”

As Beaton explains in the afterword for Ducks, the early 2000s was a time when mental health was discussed very little. “Camp life fosters a certain unique set of mental health challenges in an environment that is probably the least suited to contend with them,” she writes.

Around the same time that Beaton is working at the oil sands, people start to speak out about the conditions there—but, for the most part, they are immediately met with mockery and dismissal. When one of Beaton’s co-workers, Lindsay Bird, writes a piece about her experiences for a grassroots publication called the Dominion, the backlash is immediate: online commenters tell her to get a grip, toughen up, and stop complaining.

Though not perfect, our cultural understanding of mental health and labour has grown substantially compared with what it was a decade and a half ago. The same can be said for the discourse surrounding climate issues and environmental destruction. Despite these advances, it seems not much has changed on either front when it comes to Alberta’s oil operations. A 2021 study from the University of Alberta showed that fly-in, fly-out oil sands workers—those who work at the camps and fly home during off time—have poorer mental health compared with the general population, largely because of isolation and distance from family.

When the CBC reported on the research, the comments were similar to those Bird received in response to her article fifteen years ago. “Not for wimps. Some guys just can’t hack it,” one person wrote. “Mental health issues are common in every sect of society. Why make it about oil and gas?” said another. As protests have sprung up across the country to keep pipelines off Indigenous land, and as people decry their environmental toll, the oil industry is still booming—and workers are still being used to justify continued support for the sector. Jobs are a constant talking point in the conversation around oil, even if the workers themselves are not.

It’s clear that Beaton has crafted a thoughtful, timeless book, and it’s made all the more powerful by her illustrations. The graphic-memoir format lends itself well to a book mostly made up of dialogue, and Beaton uses this to her advantage: every conversation is meaningful, and she’s artfully crafted a narrative through her interactions with her co-workers. She showcases how disorienting and vast the industry can be—and the trauma it inflicts on her—in a way that may have been less powerful if this were a memoir composed purely of text. Ducks is a triumphant, heartfelt, and expertly told story about the cost of making a living.