“Trudeau must go or party beaten, Liberal MPs state,” went the Globe and Mail headline.

It was August of 1983, and everyone knew that Pierre Elliot Trudeau, who had won his first federal election in 1968, was into his final act as prime minister; the only question was when the curtain would fall. With an election approaching and the party tanking in the polls—27 percent approval in the summer of 1983, twenty-eight points behind the Progressive Conservatives under a dynamic new leader named Brian Mulroney—a cadre of Liberal MPs had begun openly calling for Trudeau’s ouster. “We’ll have a better chance with somebody else,” one Toronto-area MP opined. “The Prime Minister is going to have to resign,” said another. Even Liberal Party president Iona Campagnolo had been “dropping hints” that Trudeau’s time had come. Only a fresh face at the helm, they believed, could stave off electoral collapse.

Amidst calls for his resignation, Pierre Trudeau repaired to an “unspecified Greek island” with his three sons. We don’t know whether the PM discussed his political future with his boys or how deliberations over his father’s political extinction may have marked eleven-year-old Justin. But we do know that Pierre Trudeau did not gracefully disappear into the sunset. For months, he dangled the proposition of his resignation, seemingly toying with the media. Once, after rumours of a retirement announcement lured journalists and camera crews to Parliament Hill, he said, “You’ve got the month right; you’ve got the year wrong. So come around next year.” If there were an “Olympic competition for contrariness,” the Globe wrote, “Pierre Trudeau would be a cinch for the gold.”

If the polls are to be believed, it is now fall of 1983 for his son. Sixty-seven percent of Canadians disapprove of Justin Trudeau’s leadership, according to a September Ipsos poll; when asked who will make the best PM, Trudeau barely edges out the New Democratic Party’s Jagmeet Singh (26 to 23 percent), with Pierre Poilievre sailing about twenty points ahead, at 45 percent. The Conservatives have been mostly ahead in the polls since September of 2022; their most recent lead, per an Abacus poll from October, is of twenty-two points. After a stunning June by-election defeat in Toronto–St. Paul’s—a riding held by the Liberals since 1993 and considered one of their safest seats—one pollster predicted a coming bloodbath for the Liberals, in which half of their twenty-four Toronto-area seats might be up for grabs. It wasn’t just a Toronto thing. Just over a month later, the Liberals lost Montreal’s LaSalle–Émard–Verdun—another former stronghold.

Amidst growing calls for his resignation, Trudeau has remained defiant. In a recent interview, he blamed the media for amplifying “really aggressive negative views,” and he suggests that a “silent majority” of Canadians still have his back. “I am determined to lead this party into the next election,” he told Village Media.

Perhaps Trudeau inherited some of his father’s legendary stubbornness. Or perhaps the prime minister remembers what happened when his father made his fateful decision four decades ago. Pierre Trudeau did, finally, heed the calls to step aside. His disgruntled caucus got what they wanted: a new face, John Turner, to lead them into the 1984 campaign. And in the ensuing election, the Conservatives got what they wanted: 211 seats, the greatest landslide victory in Canadian politics.

Trudeau’s critics are convinced that his stepping down would give them renewed life, and that his hubris may deliver the country into Poilievre’s hands. Trudeau family history reveals that the opposite scenario is just as possible. What’s more, it suggests how Justin Trudeau may approach his own final act.

Discontent with Justin Trudeau’s leadership had been simmering for months before a mid-September caucus retreat in Nanaimo, where several MPs and former cabinet ministers publicly called for his exit. Only two Canadian prime ministers—Sir John A. MacDonald and Sir Wilfrid Laurier—have won four consecutive elections, and the Liberal brain trust concluded Trudeau was not about to join their ranks.

Yet Trudeau dug in. “I can’t wait to take on Poilievre,” he told one former cabinet minister, according to the Globe and Mail. With the NDP’s withdrawal of its support agreement with the Liberals, and with the next federal election looming, twenty-four MPs called upon the prime minister to resign in October. When he rejected that possibility, the dissenters began pushing for a secret ballot on Trudeau’s leadership.

“If we don’t step in and make a solid change here,” Saint John MP Wayne Long told the CBC in late October, “we’re going to allow Pierre Poilievre to govern for the next one, two, three terms. That would be disastrous for our country.” Politico reported that an anonymous grassroots movement warned riding associations that the Liberals were running “a distant third place” among young Canadians, who “no longer see the Liberal party as relevant.”

There is a long list of reasons for Liberal despair. A fierce anti-incumbent mood has been sinking governments around the world, including in Britain, Germany, Japan, Italy, Austria, and elsewhere. While some argue that the US election may help Trudeau by allowing him to smear Poilievre with Trump’s latest outrage, the economic fundamentals of the coming election remain stubbornly fixed. The price of rent, food, or mortgage payments is unlikely to go down; it’s possible that Trump’s proposed tariffs will make life even more expensive. Nearly half of Canadians, according to a June Ipsos poll, say that increased costs have made it hard to meet daily expenses. Seven out of ten feel the country is “broken”; among young voters, between the ages of eighteen and thirty-four, that number is 78 percent.

But the Liberal malcontents have another problem, which is that their constitution lacks a formal mechanism for forcing a leadership review before a general election loss. They could amend their constitution at the next national convention, assuming the government survives that long, meaning that the review would occur on the cusp of an election—“basically a suicidal time to try to do that kind of thing,” said Andrew Steele, a former Liberal campaign strategist. While a widespread caucus revolt involving dozens more MPs could change things, the ball remains squarely in Trudeau’s court.

It’s easy to understand why anxious Liberal backbenchers would look at the polls and think we need to do something. But it’s not enough to ask that Trudeau “step aside.” Instead, they need to ask who he is stepping aside for.

There are no easy answers. A couple of years ago, Chrystia Freeland seemed a natural successor. That feels less obvious today: a prospective Freeland campaign would, like Kamala Harris’s doomed 2024 presidential bid, carry the baggage of an unpopular incumbent; moreover, as minister of finance since 2020, Freeland is a ripe target for Poilievre’s attacks on Canada’s affordability crisis and weak economy (which he characterizes as the “worst in G7”).

Another possible contender, Dominic Barton, former managing director of McKinsey & Co., co-founded the Century Initiative, a group dedicated to seeing Canada’s population reach 100 million by 2100. If Poilievre wanted a new mascot for “radical uncontrolled immigration,” which he blames partly for “joblessness, housing, and health care crises,” Barton would fit the bill. Mélanie Joly, Anita Anand, and François-Philippe Champagne are all instantly identifiable with the Trudeau brand: any one of them represents “more of the same” at a time when voters are primed for something different.

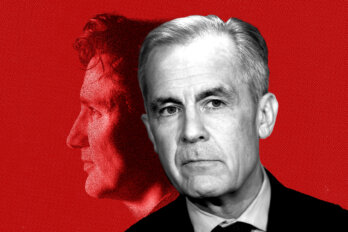

Hence the long-standing scuttlebutt about Mark Carney’s leadership aspirations. Carney, who spent many of the Trudeau years abroad, would be harder to tar with the incumbent’s record. But he remains untested as a retail politician, and his chief qualifications as former governor of the Bank of England and Bank of Canada mark him as an establishment candidate par excellence at a moment when Canadians increasingly feel that, according to pollster Nik Nanos, “the system is broken.”

Anything is possible, of course. Campaigns matter, and “whenever a party selects a new leader, the publicity around that event boosts a party’s popularity,” observes Nelson Wiseman, professor emeritus of political science at the University of Toronto. Kamala Harris enjoyed a “brat summer” before her fortunes waned.

There have been moments, most notably when Paul Martin seized control from Jean Chrétien in 2003, when a change at the top has paved the way for an incumbent party’s victory. But Martin was a unique case. As finance minister, he had earned public support for slaying structural deficits that had made Canada, according to the Wall Street Journal, an “honorary member of the third world.” At the same time, his team had been plotting for the takeover for years, Wiseman recalls. In short, Martin had secured the support necessary to beat Chrétien in a leadership review, causing him to step down.

There is no Paul Martin for this moment. More likely, it seems, would be a contemporary Kim Campbell, who took the reins from Mulroney’s Conservative Party in 1993 only to see the party reduced to two seats—the worst electoral drubbing since Pierre Trudeau had stepped aside for John Turner a decade before. Herein lies a warning for today’s Liberal dissenters. While those MPs might see Trudeau’s stepping aside as an opportunity for survival, voters often see the departure of a long-term leader as final confirmation of a party’s implosion. Rarely will voters punish a party as mercilessly as they do after a long-standing leader turns tail before an election. And let’s not forget that Trudeau’s own approval rating, abysmal as it is, is significantly higher than support for the Liberal Party itself.

“Justin Trudeau starts Canada’s election campaign as the underdog,” went an Economist headline in 2019. Back in September of 2015, a month before he won his first term in office, some polls had the Liberals in third place, behind the Conservatives and the NDP. Paul Wells labelled Trudeau an “underdog” then too.

That’s the thing about Trudeau: underdog is his default position, and overcoming the odds is his stock-in-trade. This quality speaks less to tactical genius than to something more personal. His enemies might call it hubris or narcissism; friends might call it preternatural self-assurance. Whatever you call it, this singular confidence is precisely what allowed Trudeau to prevail in 2015, what has made him the dominant Canadian politician of our time, and what now spurs him on. “Show me a poll” indicating he can win, says disgruntled MP Wayne Long. That’s weak sauce. If he believed the polls, he wouldn’t be Justin Trudeau. His tenacity, his private knowledge that he can win, derives from a deeper place.

This prime minister, it’s been said, first heard the phrase “Fuck Trudeau” when he was eleven years old. His father frequently faced hecklers on the streets of Montreal. Public anger and threats of physical violence were woven into Pierre Trudeau’s prime ministership from its inception. On the eve of his first election, in 1968, an anti-Trudeau riot erupted at a Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day parade in Montreal. A crowd of separatists began chanting “Tru-deau au pot-eau” (Trudeau to the gallows), overturning and burning police cars. When they began throwing bottles and stones in his direction, an RCMP officer tried to cover him with his raincoat, “but Trudeau flung it aside, put his elbows on the railing, and stared defiantly at the melee below,” writes biographer John English. “He stood there alone, his visage stony. The crowd, initially stunned, began slowly to applaud Trudeau’s courage.”

From the moment that Justin Trudeau stepped into the ring with Patrick Brazeau in 2012, it was evident that something of the father’s courage ran in the personal and political DNA of his son. Will Justin Trudeau—once again the underdog, spoiling for a fight against his toughest opponent yet—allow his destiny to be shaped by some flustered MPs?

Time came for Pierre, as it will for Justin. What might the father’s eventual decision to step down reveal about the thought process of our current PM? The elder Trudeau’s 1993 Memoirs reveals two clues. Narrating his famous February 1984 walk in the snow, he recalls wanting to remove his family from the glare of national spotlight. “For all of their lives until then,” Trudeau’s three sons “had been the prime minister’s children, set apart from others by that fact, accompanied by bodyguards and so on.” More importantly, he says, he had accomplished what he had set out to do. Writes Trudeau: “The philosopher George Santayana defines happiness as taking ‘the measure of your powers.’ That night I took the measure of mine. It was time to go home.”

Justin seems to have dug himself into the opposite view, that his family can persist as they have—a decision, according to the Globe and Mail, which “had already come at the cost of his marriage to Sophie Grégoire Trudeau.” If he has partly or wholly sacrificed his marriage to stay in the game, a sudden reversal of course seems especially unlikely. And as for taking the measure of his own powers, his recent appearances don’t signal a man who is in the process of letting go.

The Liberal prognosis is grim. For Trudeau to stand a chance, the government will need a major policy pivot. The Liberals could harness some of the populist economic momentum by cracking down on monopolistic practices or opening the telecom sector to foreign investment. Trudeau could make a generational commitment to restoring the dream of homeownership to the middle class. He could articulate his positive vision for Canada, as the nation he described in his father’s eulogy: a place “where simple tolerance, mere tolerance, is not enough.” A nation animated by “genuine and deep respect” for Canadians of all origins, values, and beliefs. A nation we may yet become.

Whether he will do any of these things is, of course, anyone’s guess. For all I know, Trudeau will be swallowed by the anti-incumbent wave after all—or take cover long before it arrives. But we are not the United States. We are not Britain, France, or anywhere else. Our future is unwritten, its outlines discernible in polls, perhaps, but also in the relationship between a father and son, their half-realized dreams, and long, lonely walks through the snow.