Daniel Dale sits barefoot and pyjama-clad in his Washington apartment, his mouse in one hand, an iPhone pressed to his ear with the other. It’s 8 a.m. on a January Monday, and he’s being interviewed by radio host Anna Maria Tremonti, talking to Canadians coast to coast via the CBC’s The Current. A mug of pink watermelon-cucumber juice rests by his keyboard.

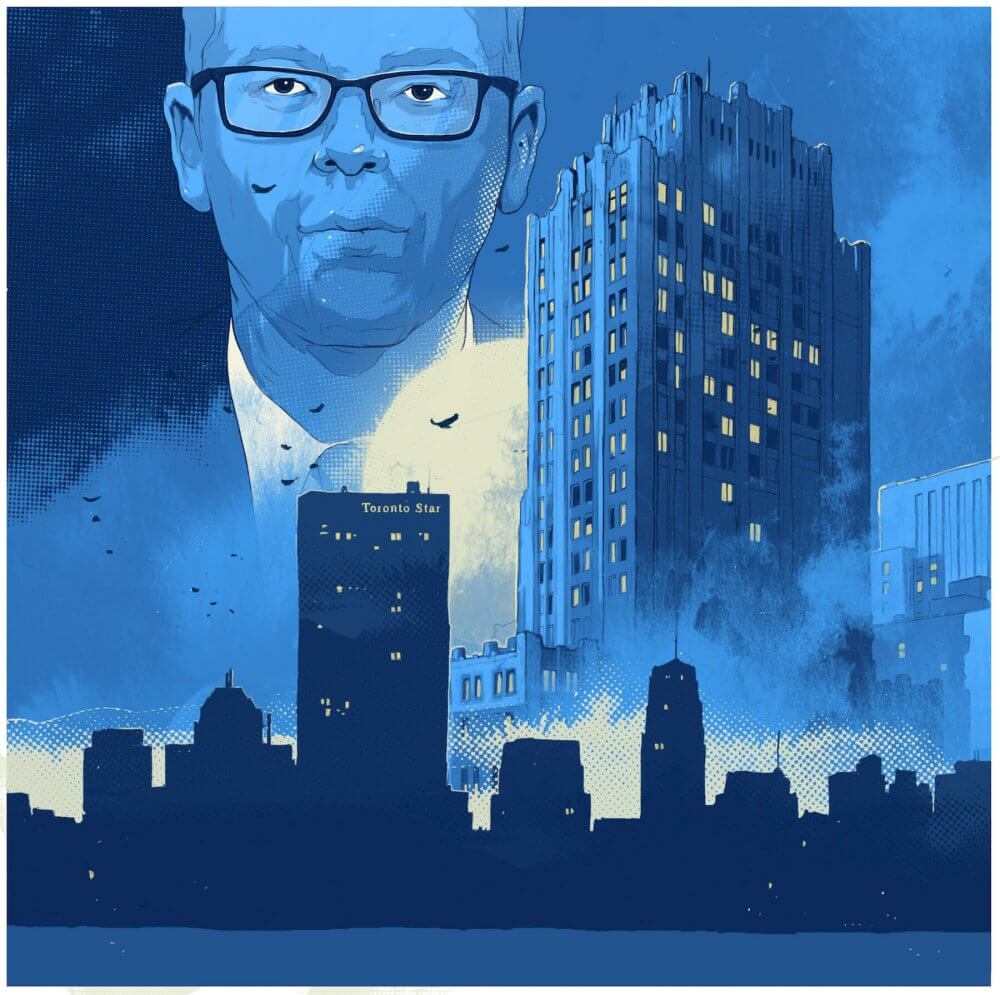

The thirty-three-year-old Toronto Star Washington bureau chief, and one of the last foreign correspondents connected to a Canadian metro daily, spent most of the night at his computer fact-checking everything Donald Trump had said publicly in the past five days. Dale has been painstakingly recording untrue statements the US president has uttered since taking office—1,075 falsehoods in the first 365 days of his administration. Having just analyzed the latest White House transcripts, he caught Trump in an ad libbed exaggeration about how “nobody knows” that the Empire State Building was built in less than a year. It wasn’t.

Tremonti asks about the journalistic highlights of Trump’s first year as president. Dale’s attention is divided, having simultaneously loaded the front pages of 120 newspapers on his monitor. No one listening would know he’s only half-focused on the words coming out of his mouth; everything he says is delivered in succinct sound bites. “There have been a lot of questions about journalism in this era and the changing media landscape,” he tells CBC listeners while scrolling to the middle of an article about the most recent US federal government shutdown. He highlights a paragraph on his screen. “But I think a lot of journalism has been fantastic,” he says.

Another guest, an Ivy League professor of communication, argues that the media are trivializing the news out of Washington. There is a long-standing tension, the professor explains, between what the public craves from the news and what they actually need for democracy to work. Despite all the investigative reporting on Trump, the public seems unable to distinguish what’s important from what isn’t. Dale nods at the professor’s criticism. Sipping his juice, he skims the front of the Virginian-Pilot. He’s onto the Charlotte Observer when Tremonti asks what the lowest point in the Trump coverage has been. “We can fail, on occasion, to delve deep into some serious policy change,” Dale replies, “because we are distracted, intentionally or unintentionally—I usually argue unintentionally—by something Trump is tweeting or saying.”

Tremonti holds Dale there. “You really have gone out of your way to fact-check the president a lot,” she says. “How difficult is that?” Dale closes the Omaha World-Herald and looks to the empty walls of his apartment. He’s been living in DC for nearly two years but hasn’t yet hung a photo and isn’t sure he ever will. “It’s more of an endurance test than a skill test,” he answers, adding that the reaction has been mostly positive. “I also do get a bunch of pushback from people who are more sympathetic to Trump saying, ‘What’s the point?’”

Tremonti thanks him for his time. Dale lowers his phone. It’s now 8:30 a.m. He checks Trump’s Twitter feed, then taps out his own tweet about the most interesting line from the 250-plus stories he’s just skimmed. The sentence, from a Washington Post book review, is about how Kellyanne Conway talks Trump out of pettiness with the line: “You’re really big. That’s really small.”

Dale fires off the tweet to his more than 300,000 followers around the globe. A brand unto himself, he is one of the few journalists whose Twitter following is bigger than the paid circulation of his own newspaper—which, for much of its 126-year history, has been the largest and most influential daily in Canada—an institution that served as the inspiration for Clark Kent’s Daily Planet. If Dale’s following is exploding, it’s because he knows that, to reach an audience increasingly spoiled for choice, he must give his readers not only the careful analysis they need but also what they want. And what they want right now is a constant stream of updates about a thrice-married, twice-divorced, foul-mouthed, attention-addled real estate mogul.

But, while Dale’s coverage of Trump has helped make him Canada’s best-known reporter and one of the most feted journalists in the entire Washington press corps (Politico included Dale on its list of breakout media stars of 2016), the institution that pays him to do what he does has been unable to generate a profit from his efforts—or any of the efforts of its roughly 170 full-time journalists. With every passing day that Dale wakes up in Washington, the Star edges closer to financial collapse. With every reporting decision Dale makes that brings him acclaim and attention, the team back home at 1 Yonge Street struggles to keep the entire operation afloat. As John Honderich, chair of the board of the Star’s parent company, Torstar, recently put it, “we’re very, very close to the end.”

No longer able to compete with the likes of the Guardian, the New York Times, and the Washington Post on stories of power, celebrity, and catastrophe, the Star has, over the last decade, been forced to do what all but one other Canadian newspaper has done: pull back its coverage. Gone are the days when stories from its correspondents in Moscow, Saigon, and Berlin informed not just the public but also federal politicians who turned to its pages for a Canadian perspective on the world. In the meantime, the brunt of the newspaper’s original foreign reportage—and much of its prestige for defending truth in a post-fact world—is confined to one reporter, working day and night in a dusty apartment. Soon, even he might be gone.

It’s increasingly hard to remember the world before the internet, when global and local happenings were announced at set times over the airwaves or dropped on your doorstep each day. “The news” was a simpler business back then, and a profitable one to boot.

But, in the last decade alone, more than 16,000 journalism jobs have disappeared—casualties of a failing business model that has seen the closure of at least 244 local news outlets in 181 communities across the country. Not all the carnage has been in print—more than one-third of jobs lost from 2009 to 2014 were from the broadcast sector, the result of Canadians tuning out cable TV. It’s all part of a large-scale redefinition of what constitutes “mass media,” as companies like Twitter, Facebook, and Google become the platforms most capable of doing what Alexis de Tocqueville, a nineteenth-century French political scientist, saw as crucial to a functioning democracy: to “drop the same thought into a thousand minds at the same moment.”

Those platforms have made the idea of print newspapers feel quaint. And yet without those published products, the majority of journalists left employed in this country would likely be out of work. Torstar’s annual print-ad revenue has dropped by almost 40 percent since 2014, but it’s still over two times greater than the $128.5 million it gets from digital ads, while the $114.3 million the company makes from print subscribers is $114.3 million more than anyone pays to read Dale’s reporting on a screen. Even though Dale reaches a far greater audience online than he does in print, and despite the fact that his paper’s digital enterprise demands a fraction of the cost of its print albatross, if Torstar were to shut down the presses and go entirely digital, approximately 74 percent of its operating revenue would vanish, cratering the entire operation.

As bad as things look for the Star, its parent company remains, for now, solvent. Which isn’t quite the case for Postmedia, which controls the majority of Canada’s metro dailies—the Ottawa Citizen, the Vancouver Sun, the Edmonton Journal, the Calgary Herald, the Montreal Gazette, and nearly thirty others. Two years ago, as the chain struggled to pay the interest on its $653 million debt, Postmedia’s CEO turned the company’s largest debt holder (a New Jersey–based hedge fund manager) into its largest shareholder. Most of the newspapers have already been stripped of their assets, and it’s unlikely any will survive should the chain declare bankruptcy.

With Postmedia on the brink, Torstar—with just over $71 million in cash reserves—is betting on a bold expansion in Vancouver, Edmonton, Calgary, and Halifax. The plan relies on the Star treating the free Metro commuter newspapers under its control as bureaus for their respective cities, rebranding them as StarMetro. As part of the revamp, Torstar hired twenty reporters to shore up the Metro newsrooms. All Metro web traffic is now being sent to thestar.com, with visitors greeted by coverage tailored to their metropolitan area. The strategy will eventually include a digital paywall. First, whet the reader’s appetite, then convert them into digital subscribers. Its success hinges partially on franchising the Star’s tradition of gumshoe reporting, delivering what outgoing editor-in-chief Michael Cooke calls “the squeal of tires and a burst of machine-gun fire.” But can the Star convince enough readers from coast to coast that one of Canada’s most storied news brands is worth paying for? “That’s not the biggest question,” Cooke says. “It’s the only question.”

Tom Rosenstiel, executive director of the American Press Institute, has worked with news organizations across the US on strategies to move beyond print. “If you’re not growing a digital future,” he says, “there isn’t a scenario where you survive.” Rosenstiel warns that the industry needs to brace itself for the time when ad revenues shrink to unsustainable levels, which he projects at seven to ten years out. If newspapers aren’t up and running on digital subscriptions in time, it will be too late to reverse course. And if metro dailies—part of what scholars have called “keystone” outlets for the way they can set the agenda for web, radio, and TV—keep falling, the inhabitants of the majority of cities across Canada and the United States will lose a crucial check on their politicians and institutions.

The absence of reporters can already be seen in the increasingly empty press galleries at many provincial legislatures. In Regina, the fourth estate has been so eroded that there are no reporters keeping a full-time eye on what’s being said and done inside the corridors of power. At the municipal level, it’s even worse. In Ottawa, a lone reporter covers the entire city on weekends, filing stories to both the Ottawa Citizen and Ottawa Sun. Meanwhile, in Thunder Bay, when the mayor was swept up in extortion and obstruction of justice charges in 2017, understaffing at the Thunder Bay Chronicle Journal caused it to fall behind the scandal, for weeks unable to disseminate much more than OPP press releases to the public. The crisis in media, in other words, has evolved from being technological to existential, as a news darkness threatens to descend wherever metro dailies are snuffed out.

Among those still working within the debris of the industry, Daniel Dale is one of the most tireless and effective. After turning his back on a promising future in business at the age of twenty-one, Dale has become the current embodiment of what his newspaper has long referred to as a “Star man”—the stereotype of the muckraking workaholic who sacrifices health, relationships, and pretty much everything short of life itself in order to chase down the next scoop.

The lineage includes Pierre Van Paassen (one of the first journalists banned from Germany after criticizing the rise of the Nazis in 1933), Gerald Utting (who vanished in Idi Amin’s Uganda for three weeks before emerging twenty pounds lighter and with an exclusive sit-down interview with the murderous dictator), Paul Watson (Pulitzer Prize–winner whose photograph of a US soldier being dragged through the streets of Mogadishu in 1993 helped change American foreign policy), and Kathleen Kenna (severely injured by a grenade after being ambushed while covering the opening stages of the war in Afghanistan in 2002). But it was Robert Reguly who set the standard. In 1966, he blew the lid off of Canada’s biggest political sex scandal when he tracked down a prostitute, and alleged Soviet spy, living in Munich who had slept with at least one cabinet minister in John Diefenbaker’s government.

Born in 1985, Dale may be the last Star man, but he is also among the first to learn his trade during the death throes of the Gutenberg era. Dale is good both in the old-fashioned way (filing political analysis to a newsroom) and in the modern way (tweeting out unique and invaluable information). More than that, he has married the two skills to become the Star’s top influencer—a person through whom a growing number of people now get their news. It was Dale who, in November 2015, travelled to Milwaukee to write about the most segregated streets in the United States (when riots exploded there nine months later, several US journalists turned to Dale’s reporting to understand why). And it was Dale who, when allegations emerged last year that Roy Moore, the Republican candidate for the Alabama senate, engaged in sexual misconduct with a minor, called more than five Republican chairmen from across the state. Few reporters thought to reach out to the party’s grassroots for comment. The next day’s Washington Post sourced Dale on Republican reaction to the scandal.

The doggedness with which Dale fact-checks Trump has set him apart from all others working inside the largest press gallery on the planet. It was in his hotel room midway through the 2016 GOP convention in Ohio that Dale realized that many news outlets, including his, weren’t doing enough to challenge Trump’s dishonesty. “I was unhappy with how we were covering his falsities,” he says. He felt that they were worthy of being a larger story in itself, rather than a sidebar to something else. Dale had been studying Trump’s delivery and detected several telltale signs that often accompanied a fabrication. Whenever Trump referred to “someone” having called or told him something, Dale would make inquiries to see if it was true. He wasn’t just googling facts. He was chasing leads, trying to catch Trump’s exaggerations on anything from terrorist activity in Afghanistan to the trade deficit with China. When he shared his findings with historians, they confirmed just how unprecedented Trump’s disregard for the truth actually was. Then Dale used a word not often found in traditional reporting. He called Trump a liar.

The 2010 election of Rob Ford, a populist Toronto mayor who had little interest in truth and its designated arbiters, had already taught Dale the power of deception as a political tool. For a long time, the Star—with a team that included Dale, Robyn Doolittle, and Kevin Donovan—stood alone in unearthing scandal after scandal about the beleaguered politician. In an effort to shatter the public’s trust in the newspaper, Rob and his brother Doug Ford routinely accused the Star of falsifying facts and fabricating stories, especially after the paper began reporting that Rob had appeared in a video smoking crack. The mayor went so far as to accuse Dale of peering into his property to ogle his children, and Ford later had to apologize. Looking back on those years at city hall, Dale says they prepared him for his current role in an environment where facts are continually derided. It was also at city hall where Dale first capitalized on what Twitter could offer as a reporting tool and distribution mechanism. A slow adopter of new technology, Dale was a reluctant tweeter at first. For a long time, his avatar was the default egg. But he learned that Twitter could be used to stand up for the integrity of the public record in real time. He had no idea, though, just how much he’d be using Twitter to hold to account a president whose chronic mendacity was difficult to counter otherwise.

He initially planned to publish a recurring list of Trump’s lies to his followers. On September 20, 2016, the project took off thanks to a tweet from filmmaker Michael Moore: “This Canadian journalist, every single day in the Toronto Star, lists all the lies that Donald Trump spoke that day. Shames the US media.” Dale recognizes that as the moment his brand went global.

It was over a year later, however, on Sunday, October 1, 2017, when Dale wrote arguably the most viral piece of journalism of his career. At the time, Trump had been escalating the rhetoric between Washington and Pyongyang. At 3:01 p.m., @realDonaldTrump fired off a tweet: “Being nice to Rocket Man hasn’t worked in 25 years, why would it work now? Clinton failed, Bush failed, and Obama failed. I won’t fail.” Dale was standing on a street corner waiting to meet with his softball team—the sport is a pastime he counts as one of the highlights of his Washington existence. Dale read the president’s tweet, and the error jumped out at him immediately. He typed out his own tweet: “25 years ago, Kim Jong Un was 8.”

He hit publish just as his friends arrived. He checked his phone after leaving the diamond and realized the tweet’s impact. Before long, it had been liked 207,312 times and retweeted nearly 77,000 times. Two days later, on Tuesday, October 3, he woke up in his Washington apartment shortly after dawn. He reached for his phone to see what Trump had tweeted in the night. He stared at the screen, dumbfounded: “@realDonaldTrump blocked you.”

He took a screencap, posted it to his Facebook page, and messaged his editor. Before the day was out, the Star readied a story about how its man in Washington had joined Stephen King, Rosie O’Donnell, and one of Jimmy Kimmel’s writers on the president’s “blocked” list. That article was packaged with one written by Dale himself and seventy-six other stories—all of which went into the next day’s edition. Over the ensuing weeks and months, as Dale added to his tally of Trump lies, his followers grew, and his reporting—such as when he dissected the legal ramifications behind Trump’s tweet on firing national-security adviser Michael Flynn for lying to the FBI—no longer just attracted Canadian readers to the Star but drew them from all around the world. He had become the most famous Star man in the history of the newspaper. It made little difference. By the end of that year, Torstar had lost more than $29 million.

Founded by twenty-one striking printers and four apprentices in 1892, the Star has had a number of near-death moments in its history. In 1899, it struggled to find its readership as it competed against the Globe as well as the Toronto Evening Telegram, the Toronto World, and the Mail and Empire. A group of Toronto elites, including Timothy Eaton, purchased the Star and hired thirty-four-year-old Joseph E. Atkinson to save it. Atkinson, who had made his name with the Globe as an Ottawa parliamentary correspondent, grew the Star’s subscriber base from 7,000 in 1899 to 37,000 by 1905. By 1909, he’d built the Star into the largest newspaper in Toronto.

Four years later, he acquired a majority interest in the newspaper, which he ran until he died in 1948. Upon his death, he willed the Star in perpetuity to the Atkinson Charitable Foundation and had bequeathed to the foundation most of his wealth. But the Star soon found itself at odds with the provincial Tories of the day who, in 1949, enacted the controversial Charitable Gifts Act, making it illegal for any charity or foundation to own more than 10 percent of a private company. It’s hard to read the act as anything but a direct attempt to kill the Star. Ultimately, five trustees from the foundation’s board bought the paper from the foundation. Included among them was Beland Honderich (then Star editor-in-chief) who, together with Joseph S. Atkinson (Joseph E.’s son) and three others, purchased the Star for $25.5 million in 1958 (the most anyone had paid for a newspaper), endowing it and their voting trusts in the company to future generations of their families. As part of the deal, the five saviours swore an oath to uphold the Atkinson principles, which decreed that the paper should always stand for social justice as well as individual and civil liberties.

For the next forty years, the Star remained a dominant source for local, national, and international news. It had a reputation for landing seemingly impossible interviews. This was thanks to its switchboard team: a legendary group of mostly female researchers who had a knack for tracking down anyone, anywhere. (Newsroom lore is that they pinpointed a source to a London subway platform and then called the telephone box nearest his location, which he picked up.)

Tenacity defined everything the Star did, and among its most tenacious reporters were Tim Harper and Rosie DiManno. Harper joined the Star in 1982, when the paper was so flush that, as he put it, “you could have lunch in the newsroom and be in the Caribbean covering a riot by dinner.” He was appointed to the Washington bureau in March 2003 but, unable to break any real ground against the Washington Post and the New York Times, preferred to cover America outside the District of Columbia. After they heard that the levees had burst in New Orleans in 2005, Harper and Lucas Oleniuk, the Star’s roving photographer, hightailed it to the city in a car. For two weeks, they documented the region’s descent into hell. When police beat a looter almost to death in the streets, Oleniuk was there to document it. When the bodies began washing up on the banks of the Mississippi, Harper was there to report on it. He wasn’t the only Star reporter on the ground. DiManno had managed to talk her way into the French Quarter, where she filed daily dispatches back to Toronto via a payphone on Bourbon Street.

The Star that Dale walked into in late May 2007 as an intern was operating at full tilt. The subprime-mortgage crisis was still a year away, as was the Great Recession and one of the most drastic drops in advertising the news business had ever seen. In the newsroom, hundreds of reporters hammered out copy on massive wooden desks. Under some of those desks were aging typewriters stashed there when things went “digital.” And in the centre of the newsroom were remnants of a pneumatic tube that once served as their instantaneous link to the old printing presses, which had been on the first floor of the building until 1992, when the Star opened the Vaughan Press Centre north of Toronto. Dale took his seat among staff who still remembered when the old presses caused the entire newsroom to vibrate.

At its core, the institution’s business strategy still resembled its Victorian beginnings: pack the pages with news its editors thought of interest or important, bundle it with ads, and then hawk it to a mass audience on the street. With more readers than any other Canadian newspaper, the Star could reach the largest share of the Toronto audience—with advertisers paying tens of thousands for a full-page ad. John Honderich, Beland’s son, was the Star’s publisher in 1996, when the newspaper started doing what every other newspaper of the day seemed to be doing: giving away its content online. Industry logic was that the print business model could be feasibly transferred to digital. All a newspaper had to do was attract enough eyeballs, and banner ads would bring in the money. So when thestar.com went live, the newspaper believed its advertising revenue was safe.

Here’s what the Star couldn’t have anticipated: it would take millions of impressions on a banner ad for it to generate the same revenue as just one full-page ad in print. The numbers never added up. This problem was made worse by the rise of companies like Facebook and Google, which both began collecting far more data from their users than the Star or any other newspaper could have collected from their own subscribers or readers. Suddenly anyone looking to advertise to a mass Toronto audience could just capitalize on all the data Google and Facebook had collected on its users and plant targeted ads inside a Star reader’s Facebook feed or Google search. Though the Star’s readership is actually larger now than it ever was (the paper and website average nearly two million readers a weekday), the paper has lost the capacity to generate the advertising revenue required to fund its journalistic output.

It’s a two-decade-old problem that has been getting worse for all news outlets. Among the first to react, the New York Times put up a paywall in 2011. Half of that newspaper’s revenue now comes from subscribers, many of them digital and located outside the city. A big part of the Times’s success has been its use of data science to analyze what readers are willing to pay for. It’s an evolutionary approach to the news that stands to transform what the Times—and the Washington Post, which followed suit—covers both in print and online. In the case of the Times, it publishes around 200 stories a day, but according to a recent report outlining its 2020 plan, the newspaper also squanders resources on stories “relatively few people read.”

At present, the Globe and Mail is the only English daily in Canada that seems to have not succumbed to the ailments of its peers. Like the Wall Street Journal and Financial Times, the Globe and Mail long ago distanced itself from the metro-daily structure and built its brand around business journalism. Though it called itself “Canada’s national newspaper” well before satellite technology in the eighties allowed it to transmit its pages to presses across the country for same-day national distribution, the Globe and Mail has, for years, been widely considered Canada’s business paper of record. For much of that time, it has been owned, in whole or in part, by Canada’s wealthiest family—the Thomsons. While the newspaper’s financial situation is not publicly disclosed, its publisher, Phillip Crawley, insists the Globe is profitable. He points to the newspaper’s paywall, which requires would-be readers to pay up to $311.50 a year to get everything that appears in print and more.

But there’s more to the Globe and Mail’s current business model. It also includes the newspaper’s use of proprietary analytics software that allows editors to place a valuation on a story within ten minutes of it being published online. “Sophi,” as the software is called, now competes with the age-old tradition of editors using their own judgment to determine the most important news of the day and allows analytics to help determine what stories get placed where on the site and in the newspaper. In essence, the newspaper has begun to give its readers more of what the software says they want. When Sophi determined Globe readers wanted more opinion, the Globe redesigned its weekend newspaper, folding the stand-alone weekday Life and Sports sections and inserting a twelve-page Opinion section. But the software has also changed the way Globe editors judge their own business content. They now know stories about PR troubles at Tim Hortons engage Globe readers for a lot longer, and get far more social-media circulation, than those about the European markets.

For years now, the Star has been using a number of data-collection tools—including software from Parse.ly, a New York–based analytics company—to amass its own advanced metrics on who its readers are and what they want to read. Not simply what they click on but what they engage with, what they’re willing to spend five minutes actually reading and then sharing via Facebook and Twitter—and what, fingers crossed, they will be willing to pay for. According to Cooke, the data points to precisely the type of investigative journalism and social-justice reporting that the paper has always invested in. The kinds of stories that take weeks and sometimes months to report—and can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. “I am warmed that our top-performing stories almost every day are the stories we care about,” says Cooke. “It’s not water-skiing squirrels.”

But even a city the size of Toronto—the fourth-largest in North America—might not actually have enough people living within it willing to pay for those stories. Which is why, contrary to every instinct that would tell it to retreat and fortify its coverage locally, the Star is redoubling its efforts to find stories and readers far beyond the GTA.

April Lindgren, a journalism professor at Ryerson University, has been studying what she calls “local-news poverty”—what happens when a community’s critical information needs aren’t being filled by news outlets. Looking at the Star’s expansion rollout, Lindgren says there’s certainly room for improved journalism in places like Edmonton and Calgary, “but is someone going to pay $20 a month for a bunch of stories from the Toronto Star about their city? If I lived in Edmonton, I don’t know if I’d see that as good value for money.” She worries the Star is putting too much stock in the argument that compelling journalism will save it. “Sure, if you look at the Washington Post and the New York Times, you would believe there is a model for this to work—but it’s not guaranteed. The Star is already a pretty robust source of local journalism, and it’s struggling.”

Daniel dale’s face is broadcast live into an auditorium filled with 125 journalism students at Carleton University. He’s on a big screen, answering questions from those looking to follow in his footsteps. They ask him about the importance of facts in the current climate. “I’ve encouraged people to make calling out false facts a hallmark and staple of all coverage,” he says. But he, as much as anyone, knows how unromantic a job defending the truth has become. The first thing Dale did when he inherited the Washington bureau in 2015 was shutter the Star’s old office at the National Press Building. He moved everything into his apartment, stuffing books and files into his kitchen cupboards, before planting himself at his desk for days on end. Someone asks how he got into the industry. He knows, given the state of the media, that it’s a question that could help guide the next wave of journalists. It’s also one of the harder questions. He doesn’t actually know how to help any of them get to where he is. Dale doesn’t say it, but he’s not even sure what the industry will look like when these students graduate.

He’s not alone. The Star has tried to adapt to the way information moves in the twenty-first century. But, like its peers, it seems afflicted by a version of what business writer James Surowiecki called the “internal constituency” problem. The industry is filled with people who still recall when their work was profitable and who simply can’t believe those days are gone. Every action the Star has taken to save itself in the current century seems only to have brought it closer to its demise. Despite booming readership throughout the Ford saga, advertising plummeted, and Torstar went from a $131 million operating profit in 2012 to just over $11 million in 2013. That same year, it experimented with a paywall but abandoned it in 2015, believing the old ad model could be replicated via a singular device: the iPad.

Few outside the Star ever thought the investment worthwhile—iPad sales had peaked and had never really taken off among younger readers, who preferred their phones. But the Star pushed forward, believing it could replicate the success that La Presse, the newspaper of record in French Canada, was having with its own app. La Presse had managed to display content so beautifully on the iPad that it attracted not just eyeballs but digital advertisers willing to pay enough to be on it. La Presse was allowed to phase out its print newspaper. Star managers were inspired to try something similar in one of the most saturated media markets in the world. They bought the rights to use the technology behind the app; hired more than seventy employees, many of them designers; and began to rethink how they packaged news. Visual and interactive content was deemed as important as the traditional investigative reports. John Cruickshank, then publisher, called Star Touch the biggest change in storytelling in a century at the Star.

The venture cost about $40 million. To help pay for it, Torstar sold Harlequin Enterprises to Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp. For nearly four decades, the romance publisher had been a lucrative investment, one of the best-performing divisions of Torstar’s operations. A big chunk of the $455 million sale went toward the company’s debt and funded the iPad app, which, while pretty, never managed to attract anywhere near enough readers or ad dollars to pay for itself.

As Star Touch faltered, the company slashed other assets—newspapers acquired in days of large-scale profit. On January 29, 2016, Torstar shut down the Guelph Mercury, a paper founded the year of Confederation and the place where Dale got his start. Two months later, Cruickshank, the publisher who’d spearheaded the investment in Star Touch, resigned. Then, to help cover the approximately $158 million in pensions and benefits to staff, the newspaper closed its Vaughan Press Centre, selling the property for $54.25 million. For the first time since 1892, the newspaper began outsourcing its printing to a third party.

In June 2017, the Star finally gave up on Star Touch. Thirty Star newsroom employees lost their jobs in a single day. “The news that our tablet product will cease operation in a few weeks is terrible,” wrote Cooke in a memo to staff. “There’s no way to spoon honey on to that.” Honderich and company needed a new plan, fast.

Shortly after his arrival in 2017, John Boynton, Cruickshank’s replacement as publisher of the newspaper and Torstar CEO, called a town hall in the newsroom. Boynton is a fifty-four-year-old turnaround specialist with no real journalistic experience but a record of success in running Aeroplan and other multi-million-dollar loyalty programs. The job of saving the Star has fallen to him. What he inherited when hired wasn’t just the fate of Torstar’s 3,800 employees but the legacy of the Star’s costliest and most valuable resource: its reporting.

According to sources, Boynton, standing near the empty desks of the men and women who’d been hired and then fired as a result of Star Touch, looked at what was left of his staff and said: “We can’t be a department store anymore.” The Star needed to transform into a publication less concerned with being everything for everyone on the streets of Toronto. It needed instead to do what tech companies like Facebook and Google were doing—study its readership algorithmically, learn what readers want, and stop feeding them what they don’t.

“We’re going to kill some sacred cows,” he said. The words alarmed many. Someone asked what the Star would consider a sacred cow. “We need the data,” Boynton replied. The response didn’t ease any concerns. In the old model, every reader counted. Soon, only those whom data science indicates have a propensity to pay may end up mattering to the Star—and any other newspaper still standing after the next presidential election. The trend won’t just redefine the value of certain journalists but the value of certain types of journalism as well.

As Boynton’s strategic plan took shape, managers left for more stable jobs in academia and communications, and unionized reporters began waiting for the company to offer its next buyout. Then Honderich and the rest of Torstar’s executive team made a move to save the company on rent. They packed up their offices on the sixth floor of the Toronto Star building and relocated to the empty spaces outside the newsroom on the fifth. The Star had sold its headquarters for $40 million in 2000, only to pay back a large portion of that money over a twenty-year lease. Twelve years later, the building and accompanying land were resold to Pinnacle, a condo developer, for $250 million. As part of the real estate development, the Star’s former parking lot is being turned into a ninety-five-storey condo tower. Many in the newsroom fear that, when the lease expires in 2020, their portion of the building will be torn down and replaced by yet another condo tower. Among the many questions circulating among staff: Where will they go when the wrecking ball comes through the window?

It’s a question Honderich can’t yet answer. As are other questions that have lingered since February 12, 2018—the day the Star announced it was suspending its paid internship program, the method by which Dale and hundreds of others got their start. The continued collapse of the business had finally made it untenable for the Star to bring in a fresh crop of journalists every year. The next day, during an interview with the Globe and Mail, Honderich pointed out that just 1 percent of the federal money given to the CBC each year would float 50 percent of the Star’s newsroom. In the same interview, he said that if a philanthropic billionaire (like Jeff Bezos, who bought the Washington Post five years ago) was willing to take over the Star, now was the time to step forward. The day after, Honderich took to the airwaves to recommend a change in tax rules to help drive advertisers back to newspapers and away from Facebook and Google. On February 14, Justin Trudeau stood in the commons and said his government had already made its choice in investing in the CBC. The newspaper industry would just have to sort itself out.

On March 12, competition bureau officials entered Honderich’s office with a search warrant. The bureau had begun investigating a controversial November 2017 deal in which Torstar and Postmedia swapped forty-one local community newspapers. As part of the deal, Torstar abandoned its titles in Ottawa and Winnipeg while Postmedia ceded the Greater Toronto Area, which is traditional Star territory. The arrangement, which allowed both companies to avoid competing for what was left of local advertising dollars, attracted ire after Torstar announced it would immediately shutter thirteen of the seventeen titles it acquired, while Postmedia closed twenty-three of twenty-four.

In that moment, as officials combed through Honderich’s files, looking for evidence of collusion, the Star seemed in absolute disarray. But the newspaper had already quietly moved former interns around the country in a preparatory move for a future when it would be a national brand.

On April 10, the day StarMetro readers were redirected to the Star’s new page for each city, the newspaper began the long process of shedding its identity as a metro daily. On that day, Star reporters walked past derelict docks where Star trucks were once filled nightly with bundles of newspapers. Past the sign in the parking lot advertising the new high-rise condos to be built on the premise. Into the lobby and past the old linotype machine that once arranged the words of Star men and women into columns of lead-engraved text and then pressed that text onto pages. Up a slow elevator to the newsroom floor where, three weeks earlier, Cooke announced he was leaving journalism after forty-nine years. He was resigning from the Star at a time when he saw “every major city and small city across this country” existing in “a dark tunnel.”

No one in the newsroom blamed him for leaving. Not even Honderich—a man born into the wealth of a newspaper his father helped save. The younger Honderich grew up wanting nothing to do with the family business but has been fully immersed in its inner-most workings since joining as a reporter in 1976. And while the Star gave him his fortune, it has also cost him the majority of it. The total value of his current shares, which a decade ago would have been worth over $115 million, now sits at less than $10 million.

Honderich takes a seat in front of a massive poster from his former office, a print from the launch of Metropolis, the 1927 dystopian film set a hundred years in the future, in which a “mediator” is prophesized to be the only thing capable of bringing together the working and ruling classes. Poignant decor for the man trying to keep Superman’s newspaper from ruin. “I’ll keep at this for as long as I possibly can,” he says. “But you can’t carry on forever.”

There’s another poster, with a different prophesy, taped for all to see on a wall in the Star’s newsroom. It’s a visual representation of the digital readership, broken into twelve distinct subsets of humanity. Beside each type is a number indicating its total percentage of the Star’s audience. And beside that number is an analysis of their “digital propensity to pay.” It’s all part of a marketing-based strategy to train reporters on what part of the Canadian public their coverage may soon need to cater to.

Among the types of humans Star reporters now understand to be the desired readership: the “wise elders” (older, culturally active, and generous with their money), who represent 9.7 percent of the audience, and “future managers” (socially progressive up-and-comers with large media appetites). Less appealing in the modern era are the “lunch at Tim’s” crowd (socially conservative bargain hunters) or, worse, the “hillside hobbyists” who, at 11 percent of the Canadian audience, have strong traditional values, live largely outside the urban centres, and have almost no willingness to pay for any online news whatsoever. But the Star still needs more data to make sure it is producing the type of journalism that the algorithms say meets the desired readership’s wants as well as their needs. The Sports and Life pages that once brought in countless ads for anything from soap to hockey skates might soon be gone, replaced by more content from the likes of Dale and any other reporters the Star can nurture from within its own ranks to replicate his success.

Boynton insists the Star still adheres to the Atkinson principles, but he speaks with less affinity for the journalism world—of which he has been a part for just over a year—than he does for the data-driven industries in which he spent the last three decades. He says he’s reinventing Torstar from its core, calls the Star a “hero brand”—a type of company drawn to powerful convictions and that markets itself as inspirational, like Nike—and considers Dale one of its many assets whose work appeals to the customer whom Boynton places at the centre of the business. “One of the things on the Star brand that customers are passionate about is politics, and US news, and Daniel happens to be in the epicentre of both.”

To hear Boynton talk, it becomes clear that some readers—which he calls an “old-school journalism term”—will be left behind. “Not everybody’s equal,” he says, as he describes the “hypertargeted execution” the Star is now following. “Name me a company that thinks all people are created equal. Name me a company that chases everybody. Name me a successful company that is all things to all people.”

What about “the paper for the people”? The promise appeared on the first edition, which now rests in his office, passed down to him from generations of publishers, encased and shielded from the sunlight like some copy of the Magna Carta. He laughs. “That’s just a slogan,” he says. “That’s not a real business strategy. This is a real business strategy.”