Lyle the raccoon writhes on the floor in agony, sweat mixed with tears dripping down his face, as his friends Neville the Dog, Omar the Spider, and Ellie Squirrel stand around him, worried.

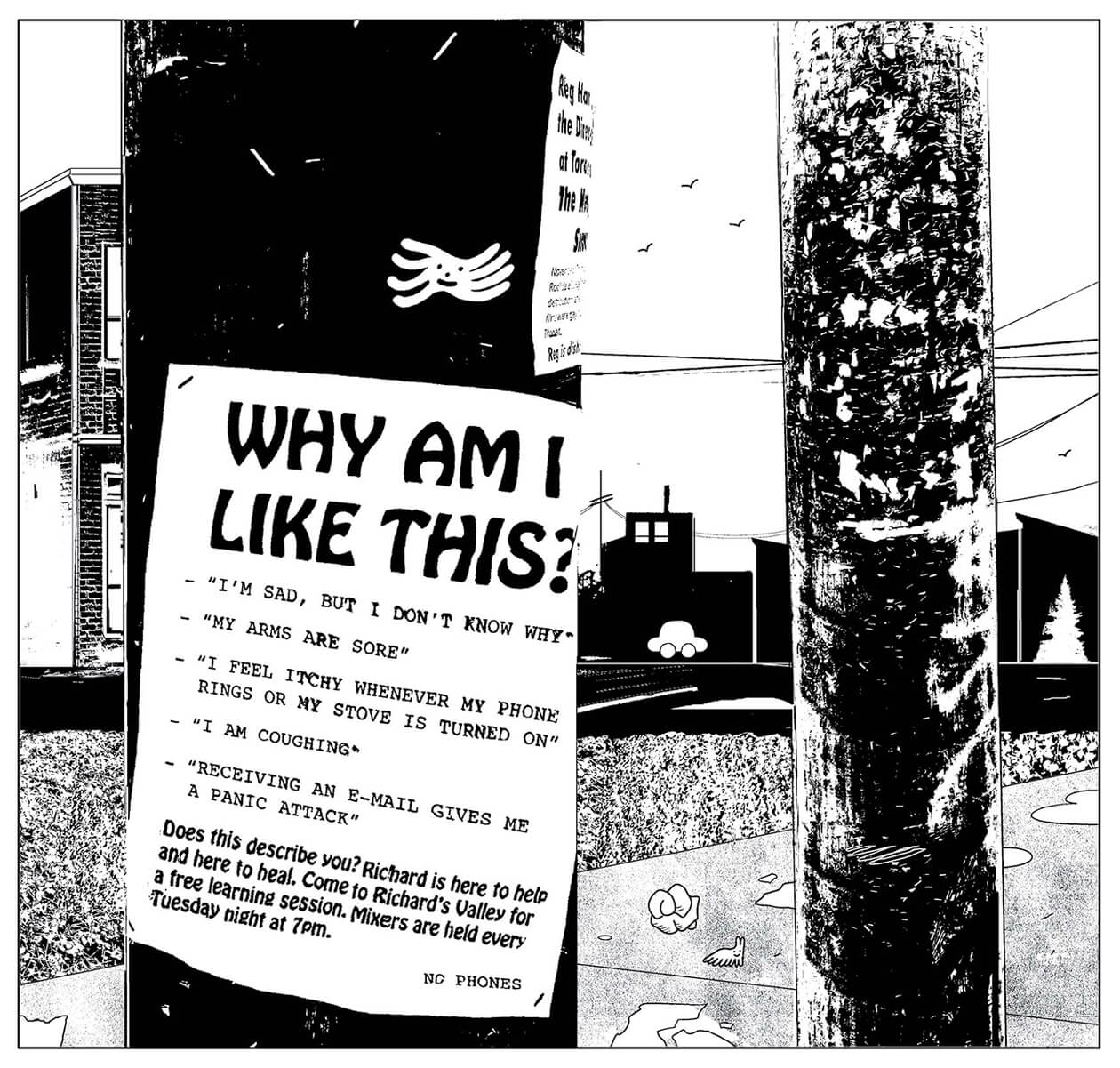

“I’m about to die,” says Lyle, and that’s not a bad guess. Not only are these friends talking animals, they’re also members of an extreme and reclusive cult whose human leader insists on treating water with “purifying stones.” Suspecting the drinking water is behind his illness, Lyle hasn’t had any in three days. His friends, who look like a Tim Burton menagerie, make a snap decision: they give him a ladleful of untreated water. Immediately, Lyle’s eyes snap open, and the debilitating stomach pain is gone. The group is overjoyed, but the celebration is short lived. When Richard, the charismatic, broad-shouldered leader, finds out about their transgression, he banishes Lyle, Neville, Omar, and Ellie, forcing them to flee the valley and search for a new community in the heart of downtown Toronto.

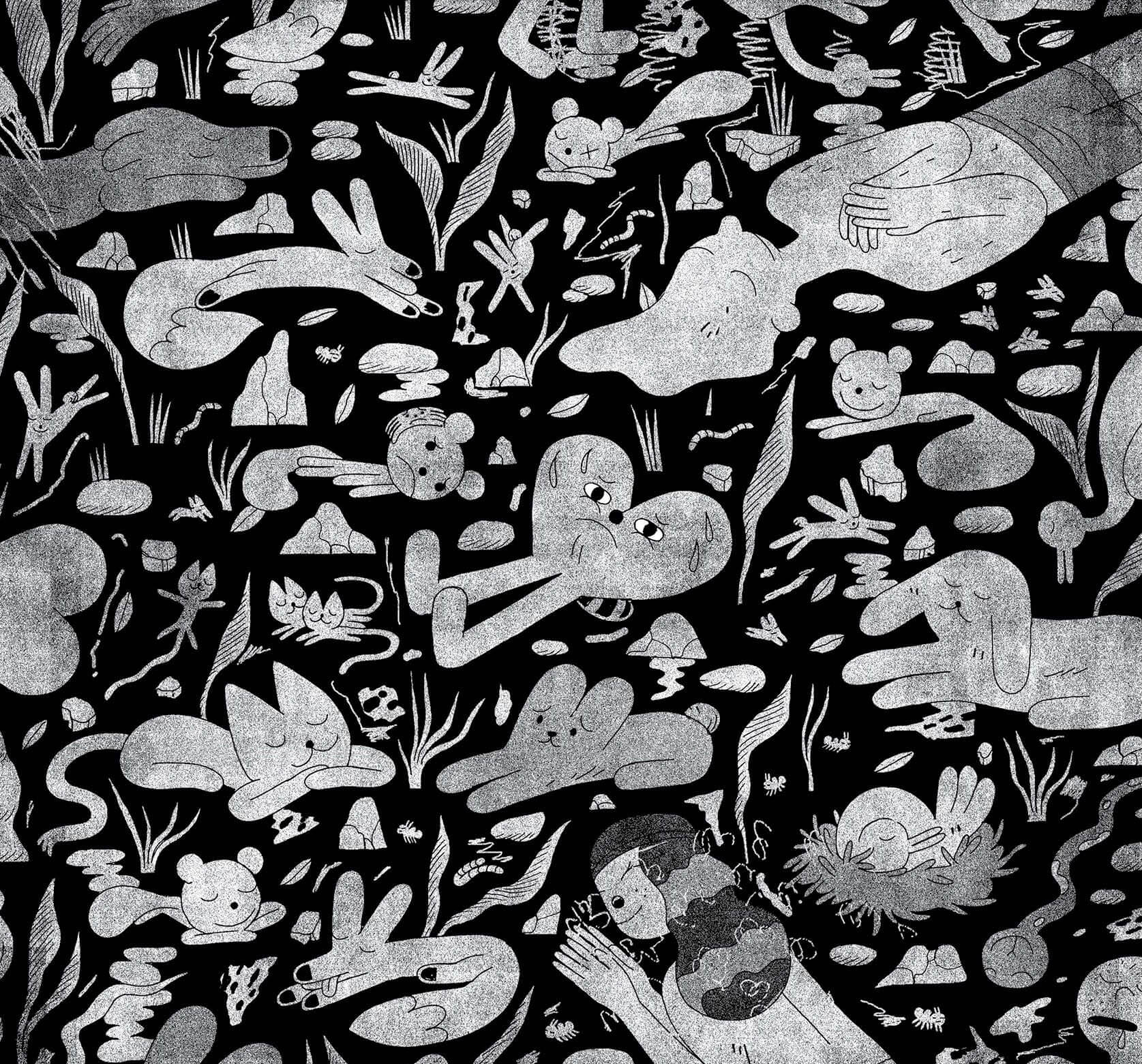

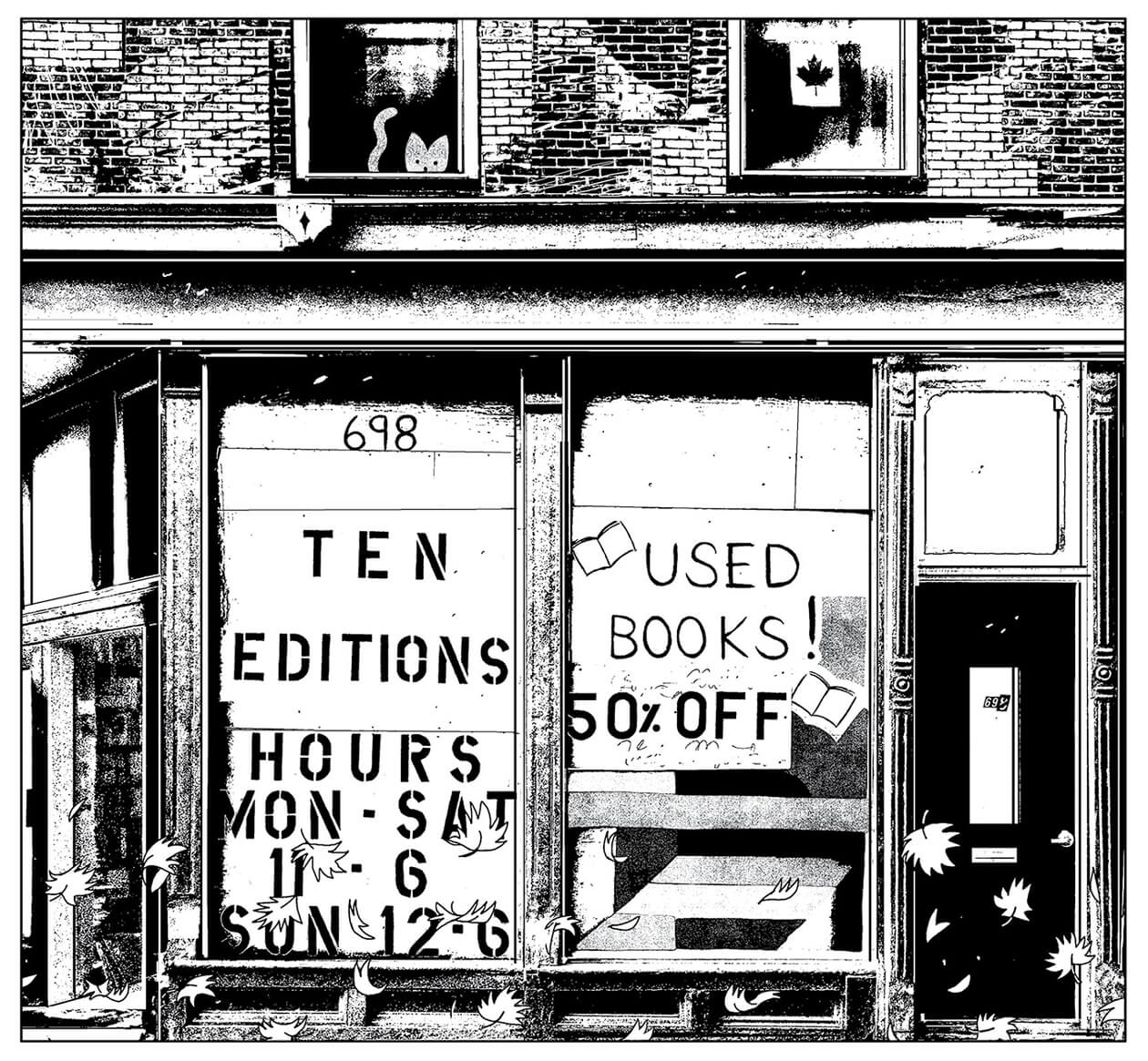

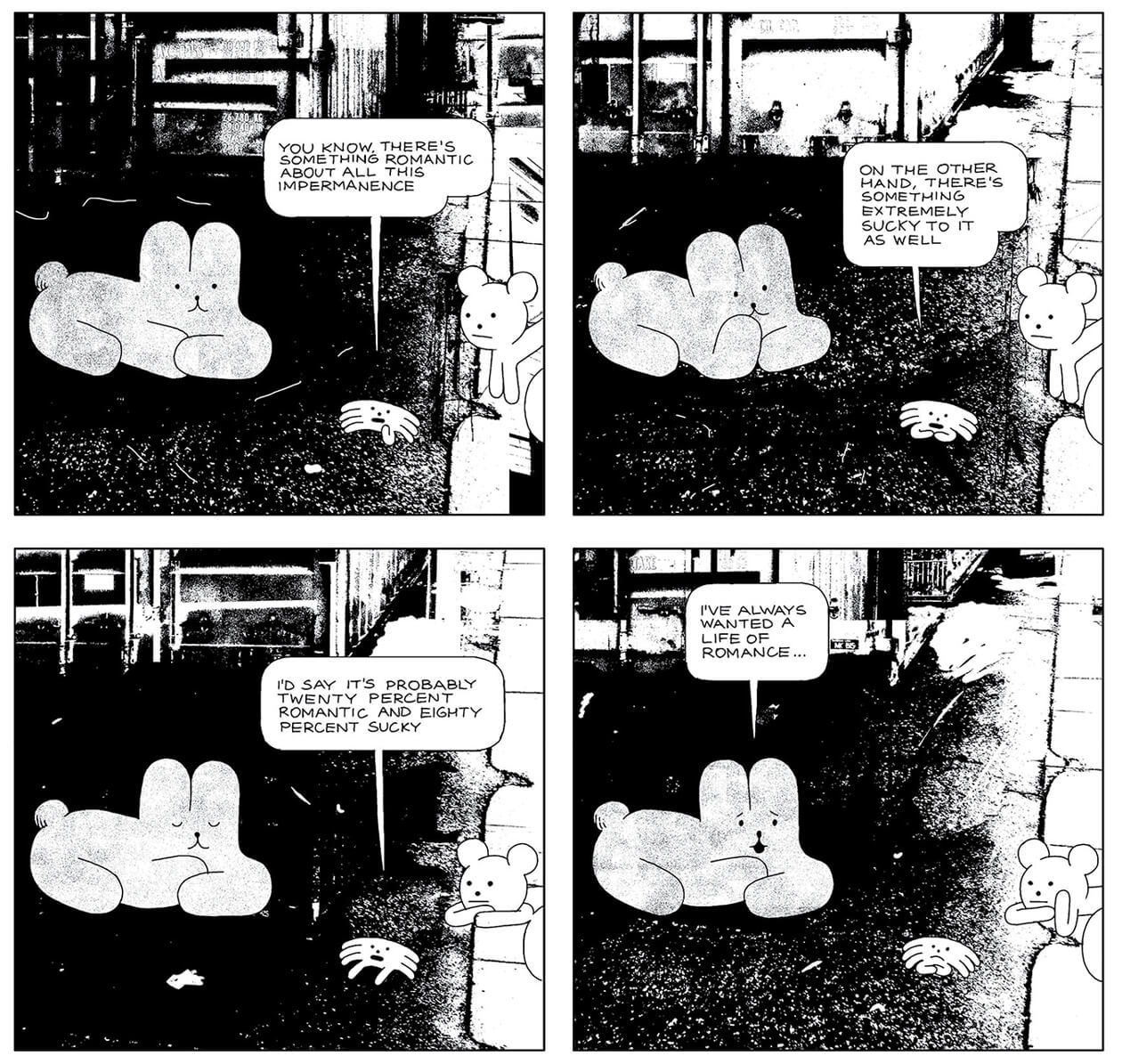

This marks the beginning of Leaving Richard’s Valley, a visually stunning, surprisingly dark new comic collection by artist Michael DeForge. It follows the furry group as it navigates the decay, debris, and clutter of the urban jungle, struggling to find a place to live and battling the forces of gentrification, isolation, and unaffordability. It is a city not unlike DeForge’s own.

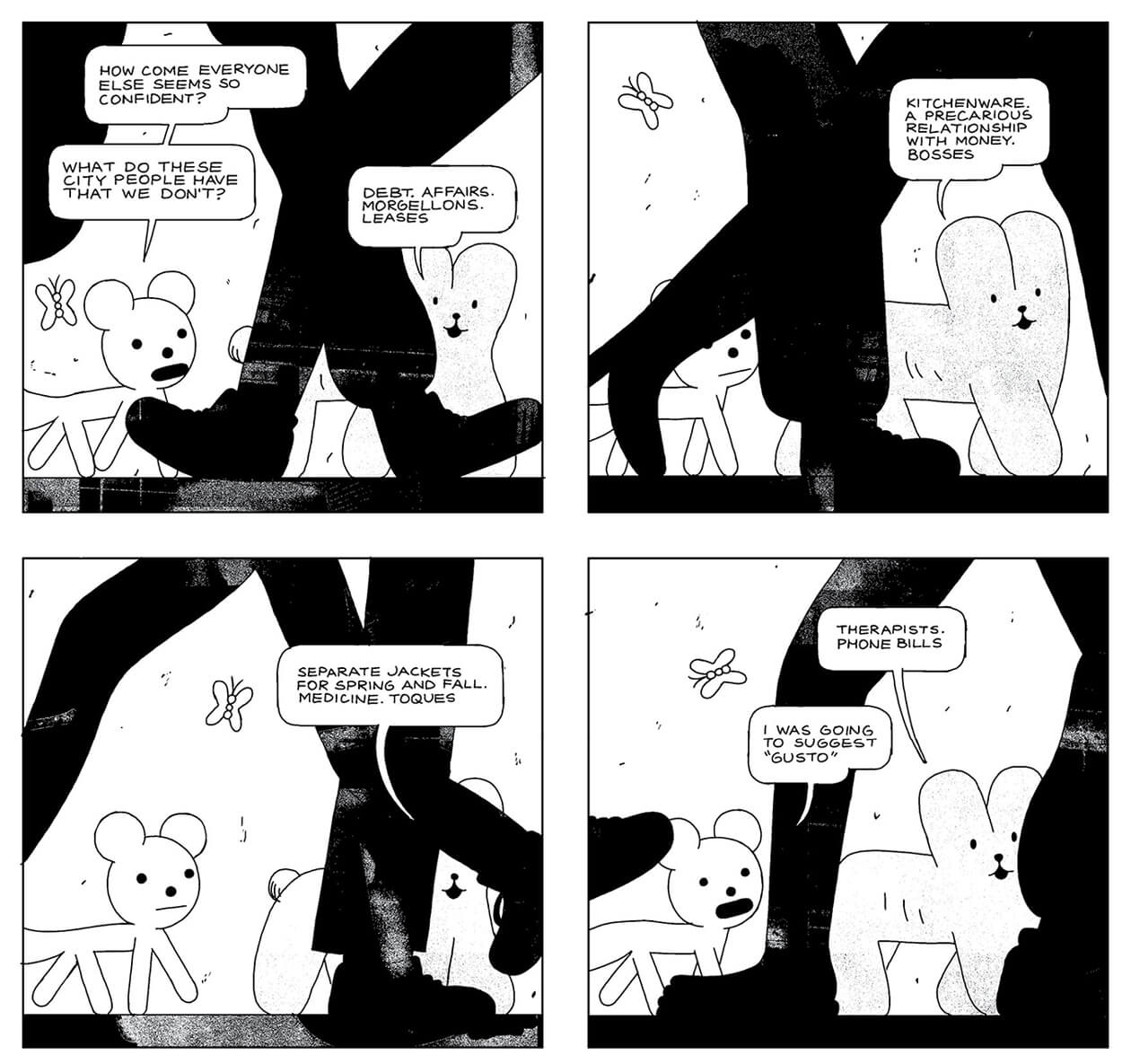

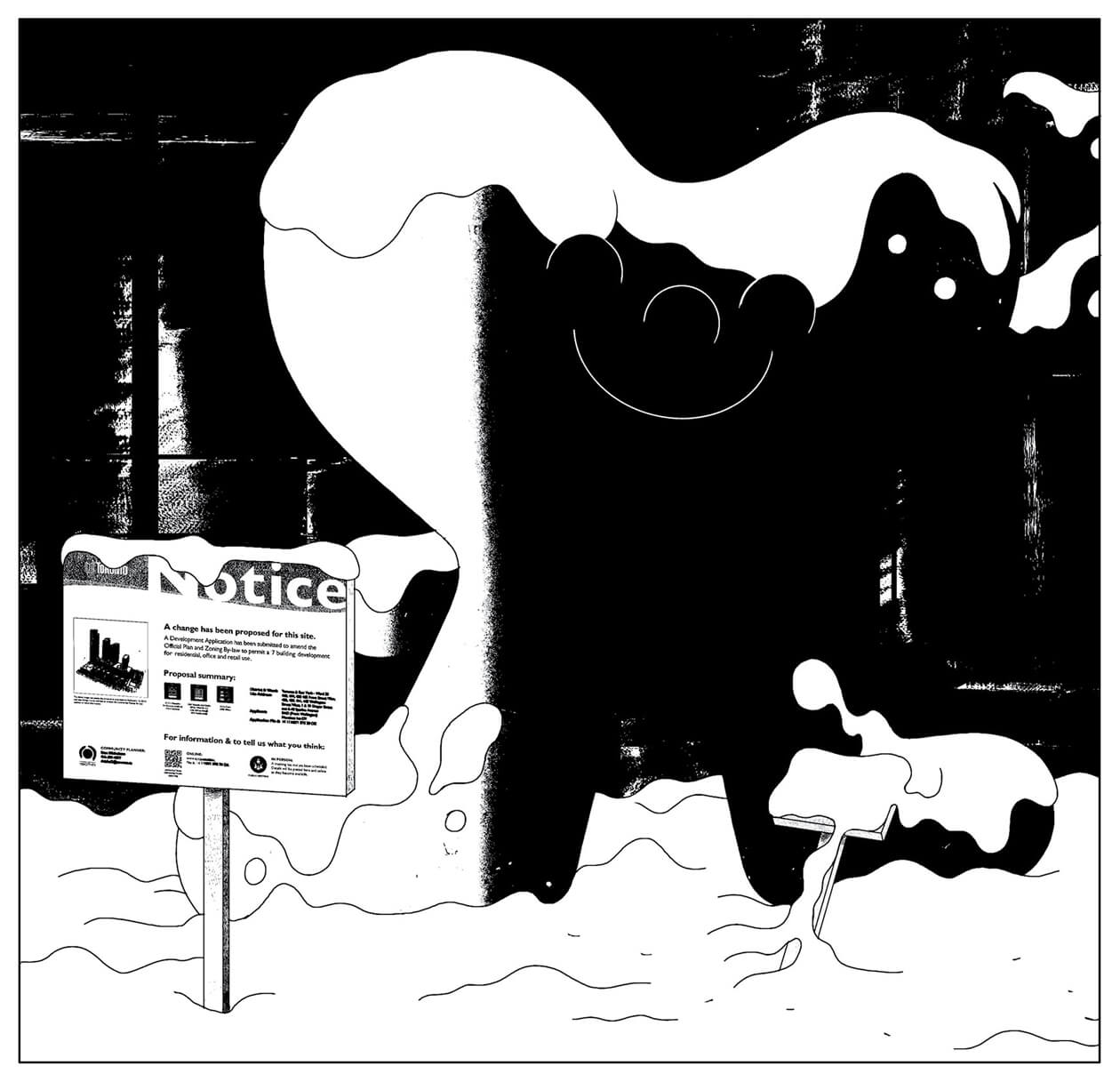

“A lot of what I was trying to write about is the way that cities are becoming less and less humane,” says DeForge, originally from Ottawa, who moved to Toronto twelve years ago and has noted the changes, such as escalating rent, around him since then. “I wanted to write these characters who feel like they’re at the whim of all of these forces of capital.”

DeForge is a professed socialist, and his views seep through the deceptively cute style of the comic, which started as a daily strip on Instagram in early 2017. At its heart, Leaving Richard’s Valley addresses issues DeForge believes plague any growing city. “I feel like basic functionalities of cities . . . are being systematically dismantled,” he says. “A lot of the accessibility and the sense of community that initially attracted me to the city and let me thrive here are just not there anymore.”

Exploring dark and political themes through talking animals isn’t new to DeForge. His previous work, Ant Colony, is a dystopian tale of a colony of black ants fighting to maintain a society while battling a faction of red ants. But, in his latest work, DeForge branches away from apocalyptic narratives, instead focusing on day-to-day struggles. Through the animals’ creation of alternate and experimental spaces—at one point, they live on a large raccoon sculpture and hold concerts in a town square—he explores ways to build communities within an increasingly isolating and unequal society.

DeForge pays homage to Rochdale College, an experimental free university started in the late ’60s that housed nearly 900 people in downtown Toronto. The college shut down in 1975, but DeForge highlights the school’s remaining legacy, which is sprinkled throughout the city, as an argument against its failure—Toronto’s Hassle Free Clinic, for instance, started as a Rochdale project and, to this day, provides sexual-health services to underserved at-risk communities.

DeForge believes Toronto has a chance to avoid becoming as unlivable as cities such as San Francisco or New York. A city isn’t about its buildings, trains, or parks but is instead about the people who live there. He asks whether, with so many disenfranchised in Toronto, we’re really creating the city we set out to build. DeForge’s work is full of juxtapositions: humorous yet dark, meandering yet pointed. Familiar spaces are made unfamiliar, and surreal tales are grounded in the suffocating rhythm of urban life. DeForge offers no grandiose solutions for city dwellers but implores us to critically examine our daily interactions, especially with people on the fringes of society.

In the final pages of Leaving Richard’s Valley, it is unclear whether the animals have been successful at carving out a space for themselves. All they can do is remain together—huddled under blankets in a park, waiting for spring. Yet they are stronger for it. DeForge wouldn’t have it any other way.