O n a warm summer evening in June 2023, I walk into a bright, modern facility in the West End of Winnipeg to attend an alumni milestone event at the Bruce Oake Recovery Centre—what the staff and participants informally call Birthday Night.

Bruce Oake is an addiction treatment centre that’s named after my oldest son. Bruce died of a drug overdose more than a decade earlier, but he’s never far from my mind—especially here. As I walk through the centre’s front doors, I see the glass memorial case that holds Bruce’s remains, and I rub the top of it to say hello, the same way I do every time I enter or leave the building.

When it comes to addiction and recovery, I’m not a professional. Far from it. Technically, I’m not even an employee at Bruce Oake. But as its co-founder, I am its biggest fan and supporter. That’s why I find myself coming by the centre most days, eating lunch with the participants and working out in its gym. When Bruce first started using as a teenager, my wife, Anne, and I didn’t have the slightest clue about addiction and what a vicious disease it is. Nor did we understand that it was also a national crisis, with thousands of Canadians dying of overdose every year.

There’s an excited energy in the gym. In the world of recovery, your “birthday” is the date you stopped using, and we’re all here tonight to celebrate three guys from the program who have achieved a full year of sobriety—the first sixteen weeks as a resident of the recovery centre, completing the Bruce Oake program, and the rest of it out in the world, taking the skills they learned in here and using them to build a healthy new life for themselves.

One graduate, who seems a little nervous, reads his speech to the audience off his phone. It consists of a series of bullet points, the first of which is simply: “I love this place.” No matter their talents at public speaking, I find all of these men and their speeches incredibly moving. They’ve been through something very difficult, and they’ve survived it. Now they’re on stage, expressing gratitude and sharing their stories in front of their friends, family, and fellow alumni. But it’s the third speaker tonight who really makes me choke up, because he reminds me so much of Bruce. Like my son, this graduate comes from a well-off family and enjoyed the kind of privilege growing up that some people think protects them from the dangers of addiction. Unfortunately, they’re wrong.

Addiction knows no boundaries, not even socioeconomic ones, and it can come for anyone.

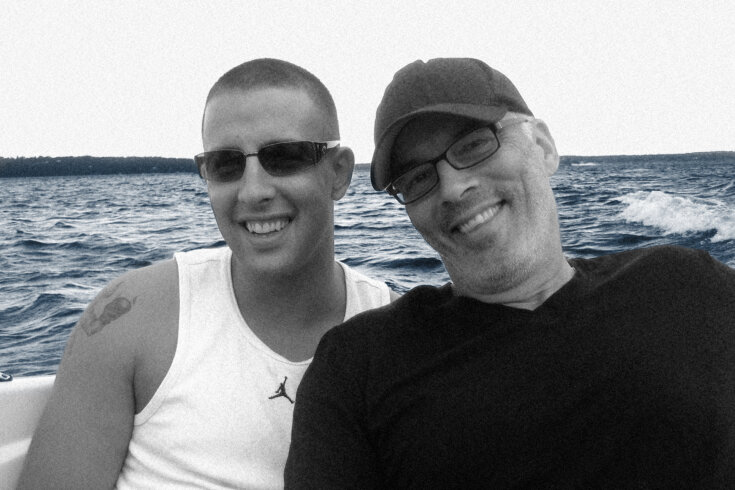

A t moments like this, I can see Bruce in my mind so clearly: a strapping, six-foot-two, good-looking boy who got the best of Anne and me. He had dark brown hair, hazel eyes, and a thousand-watt smile that turned heads whenever he walked into a room. Bruce graduated from Winnipeg’s Tuxedo-Shaftesbury High School in June 2003. But it wasn’t clear to anyone—least of all Bruce himself—what he was going to do with the rest of his life. We knew he wasn’t going to go to postsecondary, since high school had been enough of an academic challenge for him.

It became obvious to us that Bruce was smoking weed—mostly because he wasn’t particularly subtle about hiding it. He once hotboxed his mother’s van, for instance, unconcerned with how long the smell would linger for afterward. Another time, I was reaching down into the handle of my truck and came across a dime bag he’d forgotten to take with him. And once, I went down to the basement, where I discovered the window wide open and Bruce and my other son, Darcy, sitting underneath it, smoking a joint together. (In that last situation, at least, Bruce willingly took all of the blame as the older brother.)

This wasn’t a huge cause for concern on its own. Plenty of teenagers smoke weed, after all, and turn out just fine. Anne and I just hoped it wouldn’t lead to anything else.

We tried talking to Bruce about the dangers of doing drugs multiple times. I also told him there had been problems in my family, mostly to do with alcohol, and that for that reason, he had to be extra careful. But it was in one ear and out the other. Like any teenager, Bruce probably thought, Whatever. I’m young, I’ll live forever, that can’t happen to me.

During that first year after Bruce graduated, just the sound of the phone ringing would make my heart race. It was a chaotic time. Bruce had little structure in his life and no interest in any kind of honest, conventional nine-to-five job. His oppositional behaviour was as strong as ever, and the constant arguing wore us all out. Meanwhile, Anne and I continued to worry that his drug use would escalate into something more serious, especially considering what else he seemed to be doing in his free time. One day, for instance, he came home with a set of tires and shiny chrome rims for his Blazer. I asked him how he’d gotten them, since he obviously didn’t have enough money to buy them himself. He came up with some nonsense about someone owing him money and giving him the tires as payment. Another time, he walked in the door with a laptop and claimed that he’d got it from another friend. To me, this set off alarm bells that Bruce had started dealing drugs—how else was he affording this stuff? I told him to give the laptop back immediately. To Bruce’s credit, he did, albeit reluctantly.

Things came to a head one day when Darcy noticed something unusual in the ceiling of Bruce’s bedroom, and when he looked more closely, he found a vial of steroids and a needle. Darcy reluctantly showed this to Anne, and another heated argument ensued. Bruce, once again, made up some complicated lie, this time about how the steroids weren’t his and how he wasn’t the one using them.

The arguing was one thing. But equally taxing to Anne and me was how good Bruce had become at lying. It was scary how effortlessly these wildly false statements would fly out of his mouth. It got to the point where I would just assume he was lying before he’d even finished his sentence—and most of the time I’d be right.

Shortly after the steroids incident, Bruce and Darcy got into an argument in the living room, which quickly escalated into a full-on wrestling match. They crashed around the floor trying to get at one another, and Bruce broke a leg off of my favourite recliner.

It was all too much, and finally I’d had enough. I told Bruce, “I’m going to the lumberyard to get a piece of wood to fix that chair. And when I get back, you better not be here.” Sure enough, when I got back home, he’d packed his bags and taken off.

Bruce did come back home eventually, and we tried to make things work. He walked in the front door that first day a little sheepish, maybe, but nowhere near repentant. Anne and I were happy to have our son back beneath our roof, but we were also nervous. Had we made the right decision in sending him away? Would anything change, or would he just revert to his old habits?

Right away, it became clear that Bruce’s time away had mostly given him a taste for independence, and it wasn’t long before he decided to move back out again, this time for good. He and a buddy moved into a house together in St. Boniface, down the street from the hospital there.

It was stressful to have Bruce out of our sight once again, and especially so quickly after the first ill-fated attempt. At first, though, there were signs that Bruce might actually be turning things around. After moving out of our house, he managed to get a job helping an acquaintance of his hang sheets of drywall. But it was too good to be true. After just a couple of days, Bruce was fired because he was caught doing drugs—he never told me which ones—while at work.

Now, when Bruce came home to visit, he didn’t look good. He’d lost a lot of weight and was generally rundown. Anne and I told him that if there was a problem with drugs, he just had to tell us and we would help him. But as usual, he denied everything. We never gave him a drug test or anything, so we never knew conclusively, but it was becoming obvious, just looking at him, that he was in trouble.

Bruce wasn’t entirely happy with the house he’d moved into, and so he and his friend Jacob found a different place in the core area of Winnipeg. From the moment they first moved in, Anne and I grew more and more concerned about Bruce’s drug use and how the two friends might be enabling one another. But even we didn’t realize how fully Bruce had descended into the gangster lifestyle that he’d idolized for so many years.

I t all came to a boil one weekend in February 2007, when Darcy called me and told me there was a problem. “Something’s going on with Bruce,” he said. “I think he got beat up.”

My heart jumped right back to my throat. I called Bruce, and when he picked up, I could hear the fear in his voice.

“What’s going on, Bruce?”

He started telling me about a friend of his from high school who had become a member of a local street gang and was now dealing drugs. Somewhere along the way, this guy decided he was going to use Bruce and Jacob’s house as a stash house. Meanwhile, Bruce had also started “making drops”—delivering drugs, in other words—for this guy. It was a messy business to be caught up in. Then, Bruce said, yesterday the guy showed up at the house and accused him of breaking into the stash for his personal use.

“He told me, ‘You owe me $25,000,’” Bruce said on the phone. “Which is obviously bullshit, Dad.”

That afternoon, however, the gang member came back to the house—this time with an enforcer. The enforcer was holding a club, and he was there to punish Bruce for not paying the money back. When the first shot came down, Bruce told me he held up one hand to protect his head, and the bones shattered on impact. I shudder to think what might have happened to his skull had the club hit its intended target. It must’ve been a horrifying scene.

In lieu of the cash he supposedly owed them, the two men made Bruce sign over the ownership of his Blazer to them. Then they made him write out a note affirming that he was giving the vehicle away of his own free will.

There was more to Bruce’s story. Their new vehicle now acquired, the gang member and his enforcer told Bruce they might have to come back for more later. Then they ripped the gold chain off his neck and left.

Anne and I were in Moncton for my mother’s seventy-fifth birthday. Anne got Bruce on the phone. He admitted to her that he was in serious trouble this time, and then he said something that made both of our hearts sink: “I’m not a junkie, Mom. I just use occasionally.”

This was as close to a full-fledged confession as we’d ever gotten from him before. In that moment, everything changed, and we finally understood just how bad Bruce’s problems had become.

The next morning, we flew back on the first available flight and met Darcy and Bruce back at our house. I took one look at Bruce and knew right away that the story he’d told Anne about his drug use wasn’t true. He looked sickly and pale. He was thinner than ever, with darker circles under his eyes than ever before. Even discounting the broken hand, which was now wrapped in bandages, this was not a person who used “occasionally.” Bruce was clearly addicted.

So we got right back in the car and took Bruce to the Health Sciences Centre, which is the major hospital in Winnipeg. We got there around 8 or 9 p.m. and waited for several hours for Bruce to be seen by a doctor. It was another painful experience, because whatever drug Bruce had been on—meth, or maybe oxy, I still wasn’t sure—he was now coming down, and it wasn’t pretty. I sat in that waiting room with my twenty-year-old son in my lap, trying to calm him down and hold on to him. His brain had shifted into panic mode, and he was desperate to leave. It took everything I had to only barely convince him to stay. When we finally got into a room, the doctor needed all of ten seconds to identify the problem: substance abuse.

It was a whirlwind couple of weeks. In that interim period, Anne and I also had time to reflect on the nature of addiction and how it can resurface in families across generations. She used to remind me, “All I know is it doesn’t come from my family!” And that was true. Anne came from a farming family just outside of Brandon, and drugs and alcohol weren’t a factor on either side of her family tree. Whereas I knew the addictive gene was very much present in my family. So it made sense it would show up in our children’s lives too.

The other thing we used to remind each other of was that no matter how difficult the situation seemed for us, it was always much harder for Bruce. There was certainly anger and frustration in our relationship with him in those years, but underpinning those emotions was always love. Darcy used to quote a line from the comedian Mitch Hedberg, about how addiction is the only disease you can get yelled at for having. Imagine standing over a cancer patient and shouting, “What are you doing with all that cancer? Get rid of it!”

T he end began with another phone call. Anne and I were in Amherst, visiting my parents. By this time, Bruce had moved to Calgary for recovery. Jill, a friend of his there, called to tell us that Bruce had been in an accident and hit a barrier on a bridge near Rockyview Hospital. The vehicle itself was a writeoff, but miraculously Bruce hadn’t broken any bones and wasn’t even seriously injured. He was taken to the hospital anyway as a precaution and sat around in emergency for a few hours but discharged himself before he could be checked by a doctor—but not before going to the hospital bathroom and using the rest of the drugs he had on him. Jill and her husband had a three-month-old baby at the time, so Bruce couldn’t stay with them. But she came to pick him up from the hospital and dropped him off at his latest girlfriend’s place.

Once he got there, Bruce proceeded straight to the girlfriend’s bathroom and locked the door. He needed to shoot up again. His girlfriend figured out what was going on and yelled at him through the door, telling him he couldn’t do that there. She actually called the cops on him, who showed up and tried to reason with him. Irritated, Bruce took off and instead wandered down to a nearby bar. He went into the men’s bathroom there, locked himself in a stall, sat on the toilet seat, shot up, and overdosed.

When word got around the bar, an employee (who happened to be training to be a paramedic) climbed into the stall and got Bruce—who still had the needle hanging out of his arm—down onto the floor. The employee worked on him for a while, trying to get his heart beating again. The cops and the actual paramedics got there not long afterward, but it was too late. Bruce was declared dead in the morning hours of March 28, 2011.

The truth is, every time an addict uses, they are rolling the dice with their life. And when you’re talking about slamming heroin into your arm, the odds become even riskier. I remember I was once furious at Bruce for something he’d done in Halifax, and after hanging up the phone, I said to Anne, “Jesus Christ, this is not going to end until he’s dead.” It was always a possibility. And now it was our reality.

To look at it from the outside, Bruce had an ideal support network. He had a loving family, financial support, and access to some of the best treatment available in this country. And he still couldn’t do it. As if the addiction itself wasn’t hard enough, addicts also have to deal with the intense societal stigma and shame that come with it.

Most Canadians understand, by now, that addiction is a disease. And yet individual addicts are still blamed for it, as if it were simply a matter of making better life choices. But who grows up dreaming of being a drug addict? Who would choose to live a life full of such pain and desperation? Nobody. Bruce certainly didn’t. But he fell victim to it anyway.

Adapted from For the Love of a Son: A Memoir of Addiction, Loss, and Hope by Scott Oake with Michael Hingston, published by Simon and Schuster, 2025. Reprinted with permission from the publisher. All rights reserved.