The following interview between Michael Harris and Leonard Cohen first appeared in the journal Duel, Winter 1969, and has been excerpted from Field Notes: Prose Pieces 1969–2012 by Michael Harris.

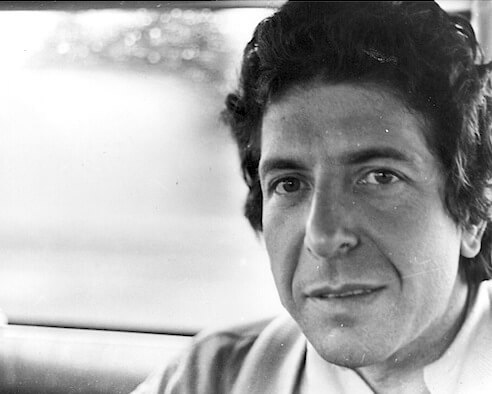

Leonard Cohen is now in his early thirties. He has published: Let Us Compare Mythologies, The Spice Box of the Earth, The Favourite Game, Flowers For Hitler, Beautiful Losers, Parasites of Heaven, Selected Poems 1956–1968, and a record entitled Songs of Leonard Cohen. At the moment he is working on a second album of songs at the Columbia Studios in Nashville. Unlike many Canadian artists, Cohen’s output has been prolific in quantity, quality, and public attention. His books, published by McClelland and Stewart, are steady sellers and his record has been bought out several times. For the first time since he can remember, Leonard Cohen is not worried about lack of money.

During a four day break in the recording commitment, Mr. Cohen came up to Montreal, scene of The Favourite Game and Beautiful Losers (his two novels), to find an apartment. The meeting took place in late October at the interviewer’s Bishop Street apartment, directly above Cafe Prag. Motorcycles, unidentifiable screams, breaking bottles and big exhaust cars all managed to be taped with great clarity. Against this sound Mr. Cohen’s voice sounded calm and soothing. He speaks prose much like he reads his poetry; he waits for a question, considers, answers with directness and quiet wit. He seems to approach and engage one problem at a time, quite unworried about the strange surroundings, the unknown people, the noise, or the fact that on the next day he would be going back to Nashville, Tennessee without having found the apartment he had come to find.

He graduated from McGill University with mediocre standing, and dropped out of a Master’s programme at Columbia. He has lived on and off the streets of Montreal, New York, London, his family, a Greek island called Hydra, his poetry, novels, one ballet-drama, songs, a small group of old friends, and other miscellaneous people, places and jobs. But now he is doing the thing he has always most wanted to do. He sings, reaching many more people than his poetry has ever done. And, as mentioned, he can live off it. He has no great plans, a blue raincoat, a dark lonely face, a frail, stooping body which consumes French cigarettes and Greek candy, among other items.

Because he is essentially a private man, and because he dislikes giving interviews which have to do specifically with his work, he only reluctantly conceded to give this one. Which turned out fine because the interviewer was also doing the interviewing reluctantly, and the starting conversation revolved around a mutual dislike of interviews, artists-on-their-art, secrets-all-over-the-block and so forth. It was therefore decided not to center around questions literary, but simply to talk, to fill in the silence with a conversation which would lead to some natural undirected conclusion.

Mr. Cohen arrived with a friend an hour early. While the interviewers finished their supper, he played a guitar—working, he said, on one of the songs for his new album that was giving him trouble. When everything was ready, Cohen took off his old blue raincoat, scratched his voluminous hair, grinned a bit, and the thing began .

Michael Harris: So most important now is the record. What kind of things are you going to do in the record?

Leonard Cohen: I have no idea of the sound I’m looking for.

MH: It is a sound, and not words?

LC: No, I don’t think too much about the words because I know that the words are completely empty and any emotion can be poured into them. Almost all my songs can be sung any way. They can be sung as tough songs or as gentle songs or as contemplative songs or as courting songs.

MH: I’ve always thought “Suzanne” was a song which should be sung by yourself someplace. I was quite surprised with the back up music.

LC: I was quite surprised.

MH: Have you any idea of the kind of sound this record you’re working on now is going to have?

LC: It’s very hard to say because it all happens in the studio. I’m working with some very good musicians and sometimes I ask them to go home and just sing it myself; or sometimes something good happens and we play it together.

I had some trouble with my first record in getting the kind of music I wanted because I hadn’t worked with men for a long time. I had worked by myself and I forgot what was necessary to work with men. I forgot how to make your ideas known to other people. The fault was completely mine. I was unaware of the techniques of collective enterprise, I just didn’t know then. I’m a little more aware of them now.

MH: What do you think of a person being secretive, singular, being uncollective or without men?

LC: I don’t think anyone is that way. Their style may appear that way but their style is just a method of relating to others. I often feel that for me to really join I have to be away. And whatever sounds I project when I’m away I feel reach the market place.

MH: Do you style yourself after anybody?

LC: No, I wish there was someone I could style myself after. But when I came of age there were very few models around. Somehow there are many models around now for people assuming manhood to model themselves after.

MH: Do you have, or did you have, a magic age when this coming of age happens?

LC: I feel I’m on the edge of it.

MH: Have you always been on the edge of it?

LC: Sometimes I’ve been in it, sometimes I’ve been past it.

MH: When were you past it?

LC: Around the time the record was being made I had very unclear ideas of almost anything.

MH: Do you call this despair?

LC: It’s one of the things I call it.

MH: Did you find any songs in that first album were done as well as on record as they had been done by yourself?

LC: I don’t think so.

MH: Why not, what’s the reason?

LC: The songs had lost a lot of their energy as far as I was concerned. But all these things are very deceptive: when you have the artist talking about his product it’s very deceptive to accept him at his word; because often it’s just that tension of exhaustion or despair or whatever you want to call it. It’s just that special magic that makes a song move from lip to lip. You know, you can never tell what energy you bestow on something. You may feel that you aren’t giving enough to it, but you may be giving exactly what is necessary. Those songs are moving through people in some way, very, very slowly. The record as a commercial phenomenon is very, very slow, but very, very steady.

MH: Does the same energy and flow apply to poetry?

LC: I think so. When I first wrote my poems not too many people were interested in them. There were some people.

I always had the idea of poetry for many people, which was very different from the kind of education I was receiving at the time, which was an elitist education. It was one of the reasons I could never make it in college.

MH: You made it at McGill.

LC: Well, I took supplementary examinations and I got fifty percent and I passed. But that was to pay off old debts to my family and to my society. I think if there had been the kind of horizontal support for dropping out as there is today, I would have dropped out.

MH: When did you first go to Greece? And why?

LC: I went in ’59. I stumbled on it, you know?

MH: Did any of the people at McGill help you? Did people like Irving Layton or Louis Dudek have any direct relationship with you: a mentor-student/master-pupil relationship?

LC: Well I think I became friends with Irving Layton, we became close friends, we still are close friends, and if he had exercised that master-student relationship he’s done it so subtly, as he would have to do with a person like myself because I don’t like taking advice. It’s not that I don’t like it, it seems that I somehow can’t assimilate it when I get it. I never know when I’m getting advice whether it’s good or bad advice. So that if Irving did in some secret part of his mind feel that he was giving me instruction, he did it in a most subtle and beautiful way. He did it as a friend, he never made me feel that I was sitting at his feet. There were many people who sat at his feet, I wasn’t one of them. We very rarely discussed poetry or art. We discussed other things. In fact, we didn’t discuss too much, we used to hang-out together. But Dudek was a good teacher, Frank Scott was a good teacher. They set out to teach me things in more direct ways, I was in their classes.

MH: Do they still watch over you?

LC: Do they still watch over me? I hope so.

MH: How did you come to change styles from The Favorite Game to Beautiful Losers and then to the really simple direct poems that were sort of sandwiched in the back of your recent anthology? Why did you change?

LC: Well, you know, you get wiped-out. And the deeper the wipe-out gets, the deeper the reluctance to use ornament or to use any of the other facilities that brought you to the wipe-out. See, if you never get wiped-out then the natural assumption is the things you’re doing are right.

MH: Doesn’t this apply all the way through though?

LC: Yes, I mean on all levels of life. You stop doing the things that bring you into the hole and I felt that I was in a hole that all the instruments I’d used to keep me out of the hole were somehow faulty.

MH: Are you a teacher?

LC: If I am a teacher I don’t think that my teachings should go into effect until I myself have reached a kind of plane where my experience would be nourishing. If people follow, if people somehow turn on to my work, and turn on to it in the way of education and think that that’s the end, then they’re wrong. I think perhaps you learn with age, the aging process is very important, I think sometimes I might be a teacher.

MH: I find it’s sort of funny and sort of desecrating, and in a way delicate, nice, that there are people who are going to do their Master’s on you, they’re going to do their theses on you and probably take you apart. How do you feel about that?

LC: I understand the phenomenon of Master theses and particularly the place I have now somehow in the cultural life of my country. You know, I understand that phenomenon, I’m not very close to that, I don’t think about that very, very often. In fact, this is probably the first time I’ve thought about it in some time, when you put the question to me.

MH: I’m not sure of exactly what I want to say next. It has to do with maybe an image you may have formed of yourself. That has something to do with this business of coming of age. But maybe it changes, all the way through, maybe the next record will be the epitome of simplicity and will be absolutely out of the hole.

LC: Well, I understand what you mean. I’ll try to relate it to something particular: this song “Like a Bird on a Wire” which I was telling you about. I tried many versions and in a way the history of that song on the record is my whole history. I tried it in many different ways. At about four in the morning I sent all the musicians home except for my friends Zev who plays Jew’s harp, Charlie McCoy who was playing the bass, the electric bass, and Bob Johnston who’s the A & R man; I asked him to just sit at the organ from time to time. And I just knew that at that moment something was going to take place. I’d never sung the song true, never, and I’d always had a kind of phony Nashville introduction that I was playing the song to and by the time I came around to start my own song I was already following a thousand models. And I just did the voice before I started the guitar and I heard myself sing that first phrase, “Like a bird on a wire”, and I knew the song was going to be true. I knew it was going to be true and new and I sang it through and I listened to myself singing, and it was a surprise. Then I heard the replay and I knew it was right. I’d never sung it true and I didn’t think I could ever sing it true again because I’m not a performer. But there is one moment and it happens to coincide with the huge mechanical facilities of Columbia Records, that’s what I call magic. And it did, it happened that way. I suppose a master, a master of chance and someone who deeply understands phenomena, could see the method and technique. I learned a lot from it, I’d like to apply it right now, we may get to that moment.

Well, what do you think of my work?

MH: What do I think of your work? Well, you see, I went to a private school and had a good home and everything was paid for and someplace along the line something went and I moved into the Hutchinson Street life for four years. And then you describe walking along Sherbrooke Street, with pieces of iron and crumbling priest-houses, and you’ve written several poems which I know and have always known from first reading onwards that said something I couldn’t say and that did the trick and had the energy that you were talking about. And on the record, for example, there are parts which came through.

LC: What you said was really beautiful: “you said something that no one else could say.”

MH: Oh yes, but the point is that’s why you remember someone else’s poetry. One remembers maybe a few lines from the young poets and from the great poets; it doesn’t matter, greatness has nothing to do with what you remember.

LC: I wanted very much to be a poet in Montreal because I wanted very much to have this conversation. When I was about eighteen I wanted very much to have this conversation. You know, to have to put out my work somehow and have it stand for a certain kind of life in the city of Montreal.

MH: Do you, apart from this conversation, ever turn and run from publicity, or from critical interviews.

LC: I think you turn and run many times, and there is always a time to turn and run. In my own mind I have the time quite clearly set out when I have to turn and run. And on the way to that moment I just put it aside, you know, I mean I could whenever I heard someone say something about my work at all. Whenever I hear the echo of the work I never really know what to say or how to accept it and I know I certainly can’t live in that world where I’m getting echoes from my own work–because then all you hear are echoes of your own work. But, at this particular moment I know this isn’t the time to turn and run so that we can discuss it thoroughly.

MH: What do you feel for the place—Montreal. I read on the back of one of the book’s cover: “to renew my neuroses” or something like that.

LC: —”to renew my neurotic affiliations”—

MH: That’s it. What do you feel about it now? Does the place ever change?

LC: It doesn’t seem to change too much for me.

MH: What about the States? Does America mean something to you?

LC: It certainly means something. What it means is very hard to say because it’s so big. But I do love Canada, just because it isn’t America and I have, I suppose, foolish dreams about Canada. I believe it could somehow avoid American mistakes, and it could really be that country that becomes a noble country, not a powerful country.

MH: Let’s talk about your movies. One of the striking, the more human parts, was when you were sitting in some sort of auditorium watching your own movie, in the movie. Did you know that you were being filmed at that point? (Note: The movie referred to is “Ladies and Gentlemen…Mr. Leonard Cohen”)

LC: I knew I was being filmed. It was a very clever device of Don Brittain, the director.

MH: What did you think of those films?

LC: Well, for one thing, I was surprised that the Film Board was treating me at all. The thing had happened in an unusual way. It had originally started off as a film on a tour of poets and I was one of those four poets. The others were Irving Layton, Earl Birney and Phyllis Gotlieb. It was a kind of promotion by McClelland and Stewart. For some technical reason only the parts of the film that dealt with me seemed to have been good so that they were stuck with a problem. They had invested a lot of bread in it and they had to make a film, so they decided to make one on me and it was a kind of salvage job so it took all the pressure off the production in a way because it was a salvage job. But he’s a very good man, Don Brittain.

MH: I saw it in the main McGill Auditorium and it was interesting.

LC: What was the reaction?

MH: First of all, the place was almost full, that was the first reaction, because people just don’t go to those films. You were filmed reading your work in the auditorium. There were lots of laughter and clapping and so on. People were very, very quiet when you read. It didn’t look like a documentary; there was the business of your embarrassment in your underwear and stuff. Have you ever thought of film as some way to expressing you?

LC: I’ve always had a fantasy that some director will find me sitting at a drug store counter, like Hedy Lamar or whoever it was. Who was it, who was that girl who was discovered in the drug store on Sunset Boulevard? A very famous actress, Hedy Lamar or somebody like that. I always wanted this to happen. Some very perceptive director would see that I stood for something very, very particular. It would take all the work away from it. I thought I would not have to create myself as an image. I would be cast as some kind of detective with wide lapels and then I could just put out my sound….

MH: Is that why you wear your overcoat with epaulets?

LC: Well, I find it very difficult to buy clothes. Because I’ve had that raincoat for ten or twelve years now, that’s my coat. I have one coat and one suit because, for one thing, I find it very difficult to buy clothes at a time like this. I somehow can’t reconcile it with my visions of a human benefactor. You know, to be buying clothes when people are in such bad shape elsewhere; so I wear out the old things I’ve got. Also, I can’t find any clothes that represent me. And clothes are magical, a magical procedure, they really change the way you are in a day. Any woman knows this, and men have discovered it now. I mean, clothes are important to us and until I can discover in some clearer way what I am to myself I’ll just keep on wearing my old clothes.

MH: Do you find yourself representative of any particular group?

LC: I don’t know. In many ways our small group, you know, I have close friends as a matter of fact, just like my clothes, my closest friends are the friends that grew up on the street with me. Somebody like Rosengarten who was a vague model for Krantz in my book. He lived on Upper Belmont and I lived on Lower Belmont; we were friends since we were children.

MH: Why did you pick Breavman as a name for the hero in The Favorite Game?

LC: As a name? I don’t recall the process. I think it had something to do with bereaved man and brave man.

MH: At the time you wrote Beautiful Losers was that when you felt yourself descending into the hole, or skirting around it?

LC: I felt it was the end. When I began the book I made a secret pact with myself, which I won’t reveal because it really was a secret pact. But it was the only thing I could do. There was nothing I could do. I said to myself if I can’t write, if I can’t blacken these pages, then I really can’t do anything.

MH: Why Catherine Tekakwitha?

LC: A friend of mine, Alanis Obamsawin, who’s an Abenaquis Indian, had in her apartment a lot of pictures of Catherine Tekakwitha around. I inquired about them and over the years I began to know things about her and then she lent me this book, which I lost, a very rare book on Catherine Tekakwitha. I had it with me in Greece and I also had a copy of, I think it was a 1943 Blue Beetle’s comic and several other books that just were on my desk. And I sat down in this very desolate frame of mind and I said, well, I don’t know anything about the world. I don’t know anything about myself, I don’t know anything about Catherine Tekakwitha or the Blue Beetle, I said, but I’ve just got to begin, and I began and wrote the book.

MH: What did you think of the various reviews of it? Does it upset you when somebody says something badly against you?

LC: No.

MH: It doesn’t matter?

LC: No, in all honesty, I don’t think I’ve ever been hurt by a review.

MH: Why not?

LC: Up to the past year or two I never received a good review.

MH: Really? Not even for The Favorite Game?

LC: Oh no, on a certain level they were all right, but nobody ever came out and said it was great.

MH: Well, somebody called you James Joyce—

LC: That was for Beautiful Losers and that was one paper, a Boston paper. It was written by a Catholic who had known Catherine Tekakwitha, who had known of the cult. A very good review, aside from that, I think he said rather humourously: “a James Joyce circumcised living in Montreal.” That was a good review, I mean, he had a sense of the seriousness of the book. I don’t mean serious in terms of the text, I mean that the effort was a life and death effort, which it was.

MH: When did you write that book?

LC: I wrote it, I think it was in 1965, for a whole year, every day, and towards the end, in the last two or three days, I was working twenty hours a day.

MH: Does money bother you?

LC: Only when I don’t have it.

MH: How do you get it?

LC: Well, it was always a problem until very, very recently, in fact, until very recently. I never really had any. I did the ordinary things people do to make money. I’ve taken jobs here and there. Then I started to sell work here and there, but I never wrote things to sell. Sometimes somebody would buy things that I’d written. I never sent things out to little magazines, poems, or anything like that. I never wanted to be in the world of letters. I wanted to be in the market place on a different level. I suppose I always wanted to be a pop singer.

When I say pop singer I mean somehow that the things I put down would have music and lots of people would sing them. I remember reading in an anthology of Chinese poetry many years ago they were discussing the biographies of the various Chinese poets and one of the poets was an intellectual poet and the other poet, I loved his work, his songs were sung by the women washing their clothes. I thought that’s the kind I want to be. But you know that all these descriptions of yourself, the things we’re talking about now, my own description of myself, those are always after the fact.

MH: Well, I don’t want to ask you about things before the fact, because that is like inquiring of the secret pact that you made.

LC: Well, there are some things that are difficult to tell and there are some things that you know you must not tell.

MH: I’ve always been interested in rituals of all sorts: anything involving things from gods to women, to writing to places. And there are secrets which are immeasurably involved with these things and that once you change rituals you have to change secrets also. You have to say at one point something you were always afraid to talk about or to say or to let somebody else know. You have to say this in order to change. What kind of secrets, or forces, do you allow yourself to let other people know? How much of you comes out? How much of you is still secret? Is it necessary for the secrecy to keep on? Do you retain some sort of sanity? Do you retain a sense of truth and honesty?

LC: I think I know what you mean. We’re always trying to get in contact with those sources, with those springs of life that you’re talking about. It’s very, very hard to make a question or an answer about them — we’re both expressing our sense of reverence to these mysterious phenomena.

MH: Do you make symbols out of them? Like, can you call them by names?

LC: I think that naming things is a great part of my craft.

MH: Is there a secrecy to them that extends between you and yourself in another reader? For example, in The Favourite Game you have Breavman sitting down in a living room with a guitar and playing A minor which is definitely A minor. Now, that’s a message which comes across to people who know what A minor is. Are you aware of that or is it just because this is what you feel and you put it down?

LC: There are many ways to tell your secrets. I think that a decent man who has discovered valuable secrets is under some obligation to share them. But I think that the technique of sharing them is a great study. And there are great masters who know how to impact the secrets they’ve learned. I think that often I’ve made mistakes, that I’ve tried to communicate my secrets. Secrets are very, very prosaic in a sense, you know, it’s like how to light someone’s cigarette or how not to hurt someone or how not to hurt yourself. I think these are how to be strong, these are really the secrets, aren’t they?

Now, you can reveal secrets in many ways. One way is to say this is the secret I have discovered. I think that this way is often less successful because when that certain kind of conscious creative mind brings itself to bear on this information, it distorts it, it makes it very inaccessible. Sometimes it’s just in the voice, sometimes just in the style, in the length of the paragraph; it’s in the tone, rather than in the message.

MH: Do you consider yourself either religious or mystical?

LC: I think I went through a saintly phase where I was consciously trying to model myself on what I thought a saint was. I made a lot of people very unhappy and I made myself very unhappy.

MH: How about religion?

LC: As I see religion, it’s a technique for strength and for making the universe hospitable. I think there really is a power to tune in on. It’s easy for me to call that power God. Some people find it difficult. You mention the word God to them and they go through a lot of difficult reactions, they just don’t like it. I mean that there’s certainly no doubt about it, that the name has fallen on evil days. But it doesn’t have those evil associations or those organizational associations for me. It’s easier for me to say God than “some unnamable mysterious power that motivates all living things”. The word God for me is very simple and useable. And even to use the masculine pronouns He and Him, it doesn’t offend me as it offends many; so that I can say “to become close to Him is to feel His grace” because I have felt it.

But, you know, my training as a writer, just in the craft, I know that I’m not going to lay too much of that sound on people because it’ll just be pointless. Unless I can find a song to place that information in; there’s no point in me just writing out some religious tract.

MH: Do you read your books over?

LC: No.

MH: Do you know any of your poetry?

LC: No. I did, I did. There was a time when I knew it all by heart.

MH: Do you get asked to read frequently?

LC: Many people ask me to read; but I don’t read at all. I feel that I’m, well, after I finished my first book, Let Us Compare Mythologies, I went away and I didn’t publish anything for five years and I feel I’m moving into that moment again, where I won’t be putting anything out for some time.

MH: Do you feel that you write for any particular group of people?

LC: I just have to say simply, no not a particular group. I know that a lot of people who are going through the same thing that I am going through or have gone through, will tune in on me and find me a good companion and I’m happy to be among them. Very happy.

I think it would be very dangerous for me to think of myself as a public figure. It’s one of the reasons why I stay out of things a lot, because I don’t, as I said before, exist in that echo of myself. I don’t like to think of myself as defining a generation or as speaking for somebody. When, love, as a cultural phenomenon, came out, in many ways my work was used somehow to demonstrate it. On the contrary, I thought that we were on the edge of a very violent period, I still do. Psychic violence anyways, if not physical violence. That aspect of ‘defining a generation’ may very well be reflected in my songs because deep in myself I know that I’m the same as everyone and what I really want to do is tune in on my sameness, rather than on my differences.

MH: Is this a change from your ‘saintly’ days?

LC: No. I’ve always felt that, I just thought that, you know, you go through a certain period when you learn chess, when you feel that maybe you have the makings of a chess master. You maybe even go as far as to buy a couple of books on chess and to study some of the great games. And maybe there’s a time when you’ve had some success with drawing, when you may think of yourself as an artist. In a similar way I had some success somehow with being able to energize people. You know, a very minor success, probably the same kind of success that anyone will have. All of us are unemployed, that’s our real problem, so I thought perhaps I had a job waiting for me, perhaps I was a saint. So I tried to conduct my life on certain saintly models that I had read about. I didn’t know that there were a great many very good and saintly people closer to the real idea of what sainthood is. But there was a time when I was perhaps, taking a lot of acid and perhaps I wasn’t, perhaps I was abstaining from drugs altogether; I remember that one aspect of my saintly career was when I abstained from almost everything. I’ve always had an attraction to that ascetic kind of life. Not because ascetic, but because it’s aesthetic. I like to live in bare rooms.

MH: Who were the singers who you’ve admired?

LC: The first singers I listened to with any real pleasure were Pete Seeger and Josh White and the singers from Wheeling, West Virginia, the country music radio station. Those were the singers I listened to with a lot of pleasure. I used to write to music all the time and it was folk music mostly, Spanish music and flamenco music.

MH: Do you consider yourself a folk singer?

LC: When I’m not actually signing, when I don’t actually have a guitar in my hand and I’m not actually singing, I don’t believe that I’m a singer at all. It’s like I have amnesia, when I put that guitar down and I start speaking prose, it just seems miraculous to me that I could ever actually get a song out.

MH: Do you know anything about William Burroughs? Have you ever read any of his work?

LC: I’ve read a lot of his stuff. I thought that Naked Lunch was hilarious. It isn’t in my nature to examine consciously the wide implications of a piece of writing. I don’t look at these things in a sociological context, nor even in a literary context. You know, when I find something that makes me laugh I think it’s good.

MH: Who did you admire?

LC: I suppose they’re in any anthology of poetry. Who knows what really turned me on? I suppose Oscar Williams anthology, that little pocket book, the Golden Treasury, Shakespeare’s sonnets, Yeats. I never took it very seriously. I somehow had a high tragic vision of my own life when I was thirteen or fourteen and I thought that I had some kind of destiny to fulfill.

MH: Do you consider yourself in any way like Martin, the mad little boy in The Favourite Game?

LC: I always loved the people the world used to call mad. I always loved people who were somehow aberrated, who seemed to be aberrated from the alleged normal. I always loved these people. I used to hang out in Philips Square and talk to those old men and I used to hang out at Northeastern Lunch that was down on Clark Street, or with the junkies. I was only thirteen or fourteen at the time. I never understood why I was down there except that I felt at home, at home with those people.

MH: When you become perfect in something, let’s say skiing, there’s one run which is perfect which you start at from the top and go down and you’re not conscious at all of your body, not even speed, you’re conscious only of your freedom. There’s a crystallization of something. When do you get that type of freedom? How do you find it?

LC: Well, I’ve had that feeling so rarely that I can remember the two or three times that it’s happened to me when I felt free. (long pause) It’s because I remember those moments so clearly that I feel so lousy most of the time.

MH: Is the moment of conception of any idea, the moment, for example, when you make your pacts, when you touch a woman, or get on a plane that’s going to take you some place. Does this have anything to do…? Oh Christ…

LC: Yes, what ever the question is . . . yes. (laughter)

MH: Do you have a feeling of progress?

LC: I don’t feel I’ve gotten better in my work because more people know about me. As a matter of fact, I would say that, if anything, my own confidence in my work has diminished with the growth of attention to it. That’s one of the reasons I can’t really be on the scene. I don’t find it nourishing if I did. There are some people who move with it beautifully, who are nourished by attention and publicity.

MH: What about your writing, when did it start?

LC: Well, I do remember sitting down at a card table on a sun porch one day when I decided to quit a job. I was working in a brass foundry at the time and one morning I thought, I just can’t take this anymore, and I went out to the sun porch and I started a poem. I had a marvelous sense of mastery and power, and freedom, and strength, when I was writing this poem. I haven’t had that feeling too often since. As a matter of fact, now when I write what turns out to be a poem, or what other people call a poem, it’s because I can’t say anything. It’s because I have to struggle with coherency in its most elementary state so that the kind of things that are in the last poems of my anthology are just one degree over, or one degree on the side of coherence. If you just took that degree away I would be left in a…I would be disintegrated. In other words, I want my poems to be, I don’t even think of them as poems, when I wrote those things they were techniques to get myself together. But I found I can’t use any ornaments, I can’t use tricks.

MH: Do you find it difficult to make out applications forms?

LC: Very difficult. I don’t have any difficulty making them out; I have a lot of apprehension that whoever reads them will not be getting the message.

MH: Do you ever think this way about your poetry?

LC: I think about all writing the same way. It takes me as long or as short to write a letter as a poem or a laundry list. Whenever I apply myself to blackening a page a certain mechanism is thrown into operation and I am facing it in exactly the same way that I have faced my life, probably all wrong. Probably clumsy and aberrated and completely mistaken; but that’s the way I happen to face myself.

MH: Do you re-write? Do you consider yourself a craftsman?

LC: I consider myself a craftsman in the way that a man who draws caricatures with his toes considers himself a craftsman.

MH: Did you hate the university that you went to for graduate studies?

LC: No. And I never find myself hating anything because if I don’t like it I don’t stay very long. But I never thought that anything was wrong with the institution. I thought those are the institutions and there are some people that are somehow nourished by them, I don’t have to be, so I’ll leave.

MH: What do you think of academia and/or academic poets?

LC: I never saw myself in the academy. In fact, as soon as I could, you know, I got work in a nightclub above Dunn’s restaurant, called Birdland. I used to read poems or improvise them while Morrie Kay and his jazz group played. I even thought that that was somehow too tame for it, too academic.

MH: How do you feel now about reading your poetry?

LC: I don’t like to read in public now. I suppose if I thought I was a lot better, if my poems could ignite, on any level, a broad mass of people. I’ve even had that experience but it’s too rare to base a reading career on.

MH: Whose poetry do you think ignites you?

LC: I don’t know, I don’t know. You know, there’s not much formal poetry in my own life. I don’t go to poetry readings. I very rarely go to any concerts even for singers.

If you see some man up there who can lay out this energy, that makes everybody feel good, that’s wonderful. And I’ve done it myself from time to time. I don’t do it anymore, maybe I should.

MH: Why did you go to Columbia University?

LC: I went there with the idea of doing something because I had this continual sense of unemployment. I was maybe twenty-one or twenty-two at the time. I thought I’d better start taking things seriously, you know, you’re twenty-two and you’re not doing anything, what are you going to do in this world? And so in some corner of my mind I thought, well, post graduate studies in English. But I couldn’t make that for more than two or three weeks. I mean, I always had this sense of unemployment; I think that’s what our disease is. That somehow some of the most imaginative people in our society are unemployed. That’s bad.

Now, I mean, unemployed both in the strict sense and in some more symbolic sense. We just are not working at our full capacity. And some people feel, you know, we have to tear the whole thing down and begin it again, that, in a sense is a kind of employment. I think that idea is very inviting to unemployed people; it really is a job. Revolution will employ a lot of people. It won’t employ me, unfortunately. I would love to be employed by it.

I think that as one of the alternatives open to young men and women today, revolution is an excellent job. And an excellent discipline, excellent training. But it’s not for me. I’ve gone into it in some ways. I even went down to fight in Cuba. I think I explored it to my own satisfaction. I know that unless I can get straight with myself no enterprise is going to be very meaningful. I think a lot of people are going to discover that too.

A very good friend of mine who wanted to be a writer and who found that he had made a mistake and he didn’t really want to be a writer, is a gardener now and very happy. I think a lot of people who simply couldn’t make it in the society as we see it now, turned to art first. And it’s still happening in this present generation. A lot of people who look at the world as they see it and look at the jobs that are offered them, simply can’t imagine themselves doing any of those things and because there aren’t many alternatives, they turn to art. They see in art the freedom and the kind of life they would like to lead, that organized society doesn’t present. But there are very few people who really have the aptitude for art. A lot of people would be a lot happier as gardeners and carpenters and cabinet makers, and I think I might be one of them. It’s certainly on my list of the things that I’m going to try. I feel a lot closer to that now, than I ever did. I hardly pay attention to what we call art. I don’t read poetry and I don’t think of myself as an artist. I’m looking around for a job. I thought it might be as a singer.

MH: And is it?

LC: It might be.

MH: Well, there must be enough confidence in it to put out a second album. Or was that because you didn’t like the first?

LC: Well, I had some songs.

MH: The sense of being on the edge of a generation, does it change?

LC: Well, as you grow older you do begin to examine that part of yourself that you might regard as exemplary. In other words, as you see another generation forming behind you, you wonder what your obligation to that generation is. And in that sense you feel yourself as a teacher. I think it’s an obligation of each generation to educate the generation that is behind it. And it’s only in that sense that I feel my life in any way exemplary. I feel it may just be a bad example; I’m interested in laying out my life as honestly as I can, and my experience, so that people who read it can benefit from that experience. Not necessarily to follow it, maybe to avoid it.

MH: Can you yourself learn from what you write, I mean, teach yourself?

LC: I find that my work, on a personal level, for me, is prophetic. So that I read it with a very special kind of interest after I’ve written it. After I’ve finished a book I sometimes read it and realise that what I’ve written has not yet come about, the sensibility is about to unfold. For instance when I wrote Beautiful Losers I thought I was completely broken, and on the edge of redemption. I thought I just can’t feel any worse. But the actual fact was, the state of mind laid out in Beautiful Losers, actually came to pass. A year or two later I felt myself in exactly that kind of situation. So I read my own work as personal prophecy. Like my dreams.

I think all my dreams have come through. I had a very curious and beautiful dream a month and half ago. It followed one of those times that I was talking about when I had an experience of total freedom. I was sitting at a cafe near The Bitter End in New York. I was sitting with some singers and some people in the music field and suddenly I became, although the feeling had grown by imperceptible degrees, suddenly I became aware that I felt magnificent, triumphant, free, open, warm, affectionate to everyone and everyone around me. Nothing changed, but I could see clearly what everyone was doing without any sort of judgement and loving what everyone was doing. And I almost hugged myself with pleasure, just of breathing and being with friends. And one of the really important things is that I saw what everybody was doing, you know, I saw them; I didn’t think of it as their game, I just saw each person’s style as a revelation of themselves. And I loved it. I loved what I saw. And I excused myself and I walked back to the place where I was staying. I walked back through the Village and it just seemed so beautiful. You know, I could see the Village as just a village on the surface of the earth and the kids walking there and the fruit sellers and the little stores. It all seemed so harmonious, like pieces of a clock and very perfect, it seemed that the world was perfect.

And then I went back to a girl’s apartment, and then it was really beautiful, she was a beautiful girl. Probably to make love, but it was like playing games. The vision slowly melted into a dream. I was walking through a village with a group of young children, probably Jewish refugees. There was a row of houses, each one seemed to represent some alternative in my life. But each place turned us down, they didn’t want to take the children. The very last house was a Swedish Red Cross Mission, where there were three beautiful women, and I fell in love with them. To me they represented Woman. And I asked, would they take the children? but they wouldn’t. Even though they refused I wasn’t upset. We left and walked down to the beach which was really bright, beautiful with the huge blue sky and miles of sand. I was standing with the children, and then Stuka bombers appeared on the horizon. And I said to the children: kneel, we are going to say a prayer. And the bombs started to fall, but no one cared.