When the rights to Jon Klassen’s first children’s book, I Want My Hat Back, were being auctioned, he recalls that one potential publisher was aghast. The story follows an affable bear who goes searching for his lost red hat, querying a series of animals as to its whereabouts. This sounds like a fairly standard plot for a kids’ book—until you keep reading and learn that the bear eventually gobbles up a red-hat-sporting rabbit who has clearly lied about their culpability in the theft. The wary publisher, Klassen tells me, felt it was barbaric to end a children’s book on a death, even one that occurs off-page, and suggested that the bear could instead beat up the rabbit—which Klassen felt was a much more monstrous conclusion.

I Want My Hat Back was published with its original ending in 2011, marking Klassen’s first solo project as both author and illustrator. (He had previously won a 2010 Governor General’s Award for English-language children’s illustration for a book written by Caroline Stutson.) Throughout his career, he has remained steadfast in trusting that his readers, even preschoolers, are capable of understanding and appreciating challenging emotions and darker themes. Adults, Klassen says, “have this reaction to death where it’s a personal fear.” Kids “treat it like anything else—they just want to ask questions about it.” The following year, Klassen published the second in what would become a trilogy of hat books, This Is Not My Hat, which included a similarly dark plot and for which he became the first person to win both the Caldecott Medal and the Kate Greenaway Medal, two prestigious awards in children’s literature, for the same book. Both titles spent more than forty weeks on the New York Times Best Sellers list.

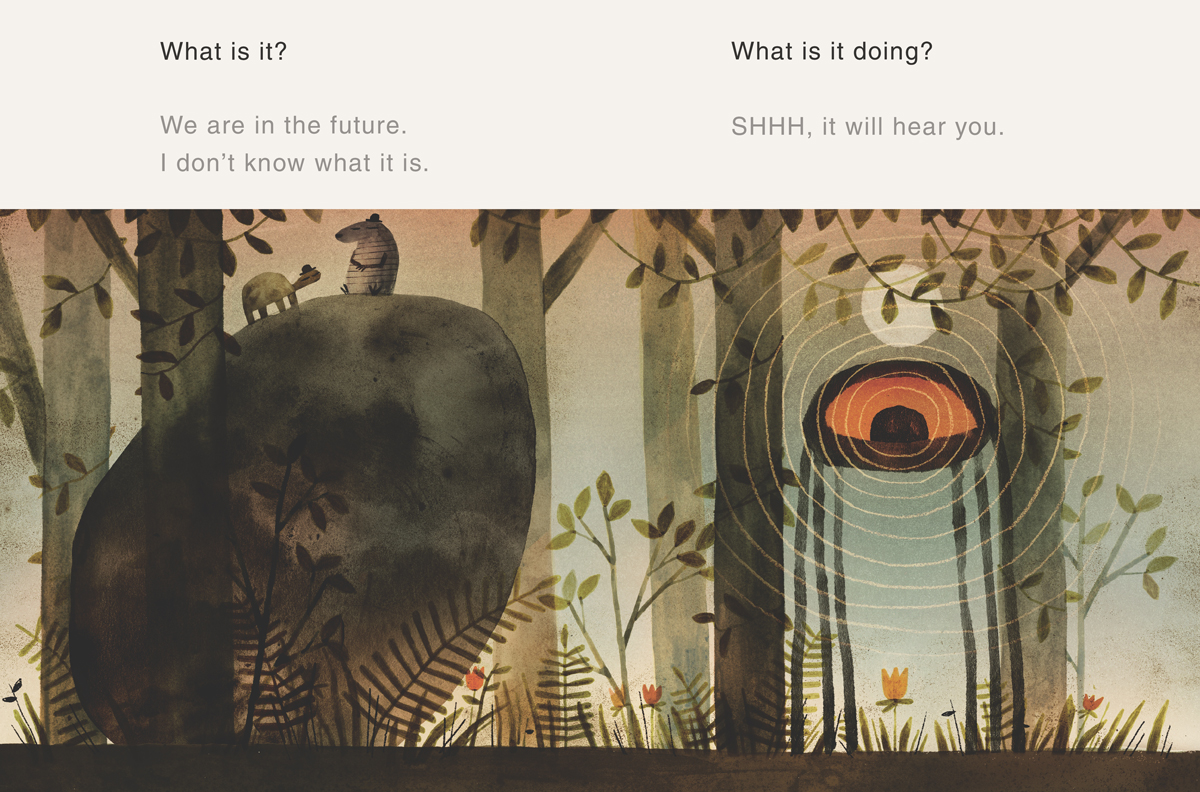

This sense of complicating expectations is also evident in Klassen’s latest book, The Rock from the Sky, out in April. It opens with a turtle comfortable in his “favourite spot” beside a pink flower. The turtle is unwelcoming of change, even when a prophetic armadillo appears and tries to get him to check out a new spot, warning of a “bad feeling.” Overhead, a giant rock is hurtling earthward. The turtle is obstinate, unflinching in his position, and often quite mean. When the meteor—a known yet still surprising threat—slams into the turtle’s beloved spot, everything changes for the turtle, who narrowly avoids being crushed, and for all creatures. The meteor offers a new perspective, new dangers, and a glimpse into the future. (The book’s particular relevance to our current moment was largely unforeseen; Klassen and his publisher finalized it the same week, early last March, that the WHO declared a pandemic.)

Coming to terms with uncertainty is a running theme throughout The Rock from the Sky. Rocks are falling. More rocks may fall. They could hit us. Life may change dramatically at any moment. “I was interested in finding ways of talking about potential problems that you are never going to understand—and maybe there’s no reason for them,” Klassen says. “That rock doesn’t have an agenda, we don’t know what set it on its course, we don’t know where it’s from, but now it’s part of your day. I think that’s how kids feel a lot: they have to function in a world where they understand that they don’t understand.” When Klassen speaks, softly yet ebulliently, he obsesses over the elements of the form, bouncing from fonts to colour theory to dramatic structure to Alfred Hitchcock’s delineation of surprise versus suspense.

Klassen was born in Winnipeg; after preschool, his family moved to southern Ontario, where he attended elementary school in Markham before moving to his father’s hometown of Niagara Falls. Now thirty-nine, he doesn’t remember much of those early years in Manitoba, but prairie imagery is evident in his latest book: the flat land and that big sky and those lingering sunsets. For years, Klassen found himself drawing a particular kind of tree, again and again, before he realized that he was attempting to recreate the big elms that had lined his childhood street in Winnipeg. His foundational years in Niagara Falls had a larger influence on his illustrations. Even in the early 1990s, everything in the town felt stuck in the 1950s: the boulevards, the architecture, the hanging on to Elvis Presley and Marilyn Monroe. Most of Klassen’s early reading material was found in his father’s childhood bedroom, which was filled with faded books from the ’50s. The artistic style he later developed has a throwback feel—a soft, muted palette akin to a midcentury postcard. “I’m kind of scared of colour,” he says. “Unless it’s meant to be symbolic and it’s meant to stand out as a point.”

Children’s picture books are a tricky genre, where an author has to appeal both to a parent in a bookstore as well as to a child at home. “I’m not sure kids concern themselves with how the books look, particularly,” he says. “I don’t think they are attracted to great illustration versus bad illustration.” Meanwhile, Klassen offers adults something they’d be proud to display on a coffee table—subtle, unobtrusive, elegant. For children, he brings what he thinks they connect to most: an engaging narrative. For the story, he aims to land both crowds, “and hopefully the kids first,” he says, not through oversimplification but by placing trust in the sophisticated mind of a child, believing that they will get it.

When Klassen moved to Los Angeles, in 2005, after graduating with a diploma in classical animation from Sheridan College, he noticed a trend in animated features for children that fell into the trap of splitting them off from adult viewers—writing narrative or humour for two separate audiences. He cites 2001’s Shrek, which had jokes for the kids and very separate jokes for the adults, as an example. “We can do better than that,” he says. He has noticed his four-year-old son react to a kids’ show or book and look back at him with the glee of simple comprehension. “He’s almost excited that he got it,” Klassen says. “There’s an excitement that you’re being trusted with that amount of joke.” In The Rock from the Sky, there’s slapstick (when the turtle falls off the meteor and lands on his back) but also irony (when the turtle and the armadillo are dreaming of an idyllic new future and an Eye of Sauron-like alien appears and begins zapping flowers) and even morbid humour (no spoilers for that one).

Listen to an audio version of this story

For more audio from The Walrus, subscribe to AMI-audio podcasts on iTunes.

Klassen pushes this trust beyond humour, believing that children will be drawn to characters that don’t fall into any classic protagonist-versus-antagonist rubric. While he was working on The Rock from the Sky, for instance, Klassen got stuck wondering how to get his stubborn turtle out of the way of the meteor—until it dawned on him that the turtle may move to join the armadillo and the snake after all if he grew envious of their friendship. His characters are rarely purely good or bad. Instead, there is ambiguity in each of their arcs, motivations, and actions—that way, when one of them does something dark, it never comes across as a gratuitous trick or shallow plot device. Above all, his latest characters share an unshakable hope in the face of challenge and confusion: the turtle climbs atop the meteor to find a new perspective, the armadillo continually tries to include the turtle, and the snake relishes the simple things. “Now they know that rocks fall from the sky,” Klassen says, “but they’re still having arguments over the sunset and they’re still taking naps and working on a relationship that has problems. They don’t freak out—they don’t spend the rest of the book wondering about the rock; they take a nap next to it.”

Klassen, now settled in perennially sunny southern California, relates this plucky optimism to an aspect of living in Canada that he dearly misses. “I didn’t like the cold when I lived there, but I miss the feeling that a whole city wakes up to the same problem in a morning,” he says. “There is a unifying feeling to that. And you can feel it when you’re in those cities—everybody is digging out at the same time. It has an effect on your mentality and your feeling of what you’re capable of—and what you’re not capable of—controlling.” There are sweet lessons in The Rock from the Sky for adults and children alike. Keep dreaming of the future even if it may seem dark. Don’t be scared of new perspectives. Listen to others, for they may offer help. But it’s the themes of death, uncertainty, and fate throughout Klassen’s body of work—as well as the spectrum of complicated emotions including jealousy, revenge, and judgment—that set him apart as a children’s writer and illustrator. “A lot of things that are going to happen to you are outside of your control, or they’re not necessarily deserved,” he says. “What happens in the hat books is not necessarily commensurate with their actions. No one has it coming that much. But it still happens. You still stole a bear’s hat.”