Two parka-clad figures trudge across an imposing, snow-covered landscape. Their names are Amka and Pilip, and they are Inuit teenagers from Pangnirtung, Nunavut. “Amka, this is crazy,” says Pilip, referring to their plan. “You keep saying that,” replies Amka. “But you’re still here.”

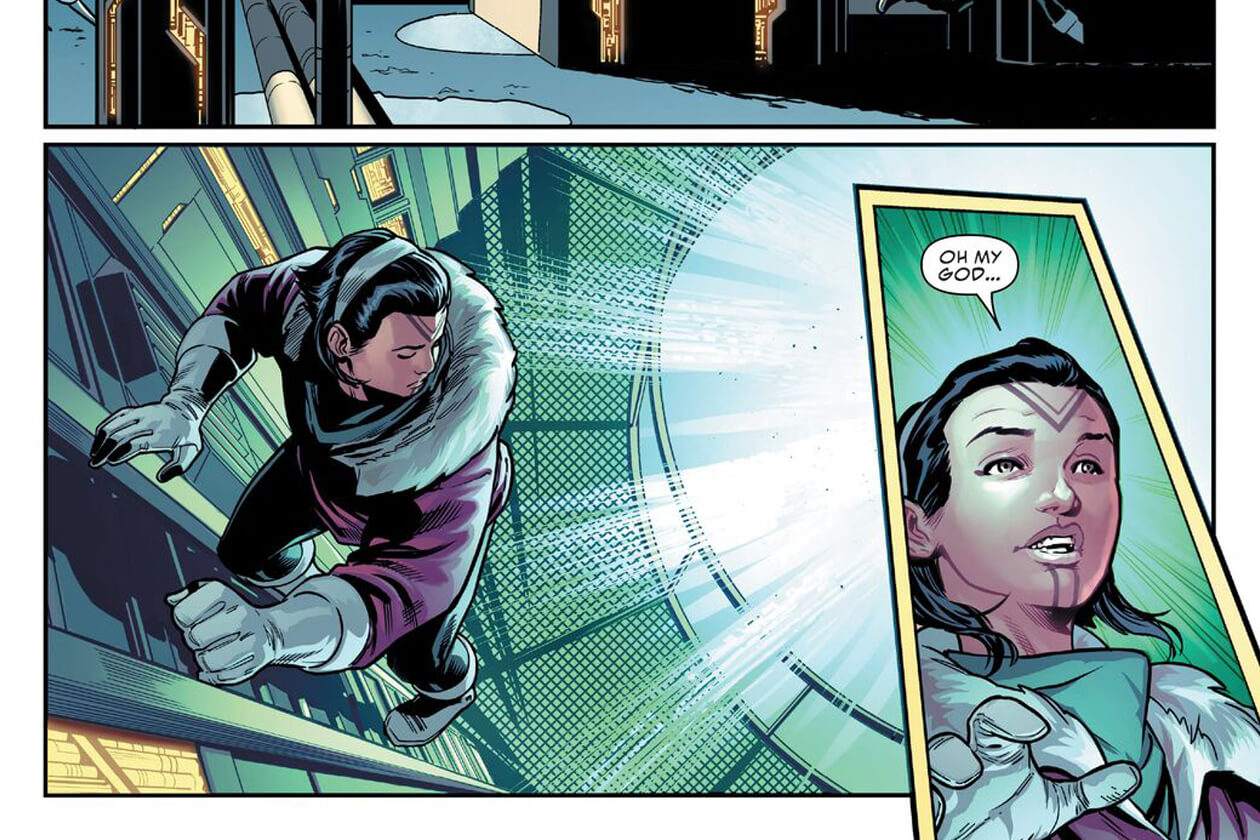

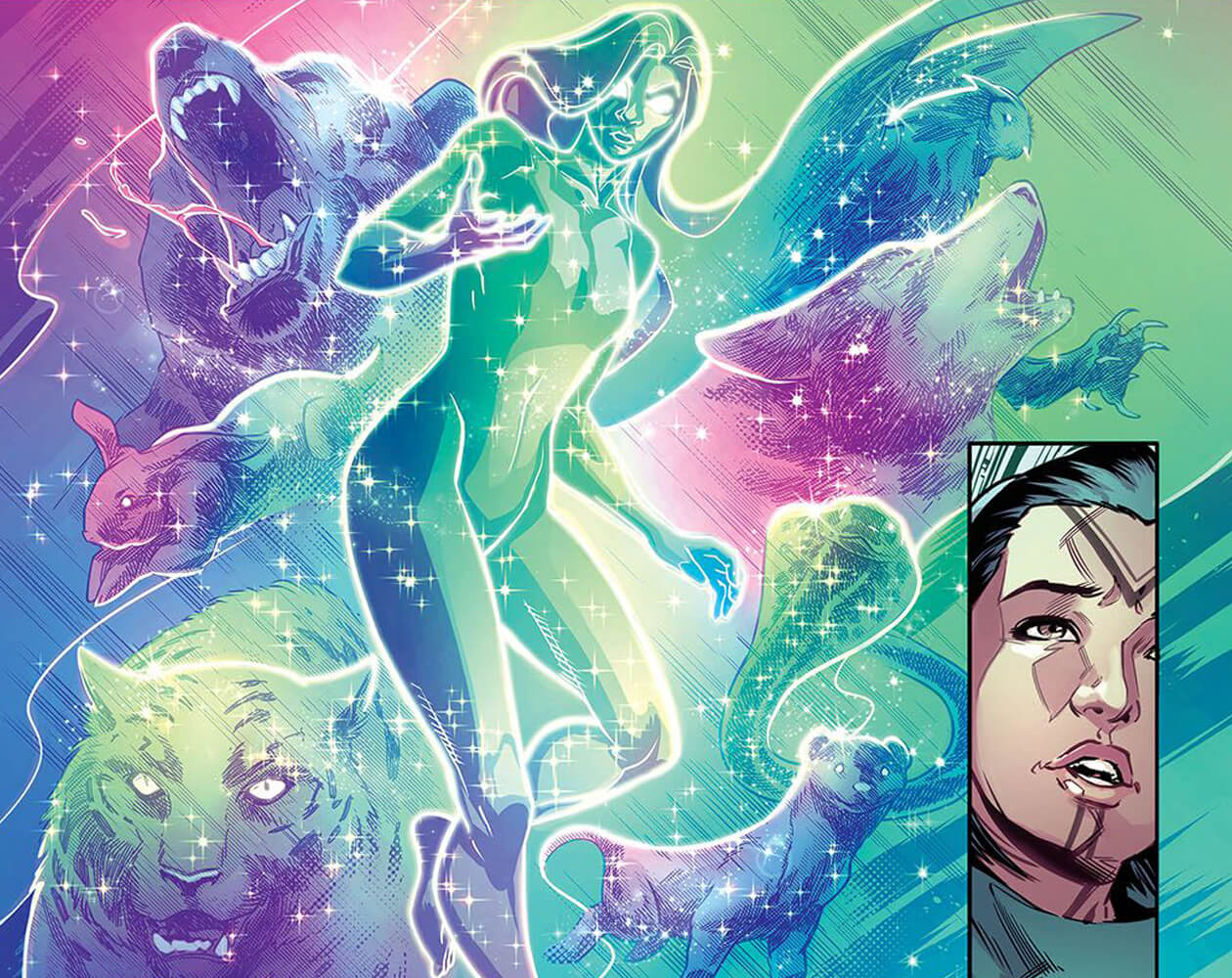

Amka is determined to investigate a mysterious, futuristic factory that seems to have materialized overnight. She eventually discovers, at the heart of the factory, an imprisoned being called Sila, the Soul of the North, whose mystical powers are being exploited as an energy source. A battle ensues between Amka and a cadre of robot drones. When she shoves the drones into the containment field surrounding Sila, the explosion frees Sila and leaves Amka badly injured. She collapses, sure she’s going to die. But she doesn’t; instead, infused with Sila’s power, Amka is reborn.

These events occur in issues #19 and #20 of Champions, a Marvel series that introduces us to the superhero career of Amak Aliyak—soon to be known as Snowguard. The next time we see Amka, in Champions #21, she’s assumed the form of a giant, seemingly indestructible white wolf with glowing purple eyes. By the end of the issue, the factory has been destroyed, the supervillain who built it has been corralled, and Amka—back in human form but still imbued with Sila’s power—has accepted her mother’s blessing to use her shape-shifting abilities to become a globe-trotting crusader. Amka is exhilarated, as though the ability to grow wings and soar—which she does on the final page of the comic—is something she’s been waiting for all her life.

That Amka is a girl already makes her a rarity within the superhero genre. According to Carolyn Cocca’s book Superwomen: Gender, Power, and Representation, as of 2016, only 12 percent of the protagonists in mainstream American superhero comics were female. That Amka is Indigenous makes her rarer still. According to Cocca, female characters across mainstream media who are also racial or ethnic minorities typically make up less than 5 percent of protagonists.

Cocca can be forgiven for not providing statistics about the number of female characters currently starring in a mainstream American superhero comic who are Inuit and hail from Nunavut. As of this writing, Amka is the only one.

Amka isn’t Marvel’s first superhero from Canada. The most famous example is almost certainly Wolverine, born in northern Alberta. He joined the X-Men after quitting the Canadian secret service, which, in Uncanny X-Men #120 (1979), is revealed to manage a team of superheroes called Alpha Flight. Also on the Alpha Flight roster were two Indigenous members—Dr. Michael Twoyoungmen, a.k.a. Shaman, and Snowbird, the daughter of an Inuit goddess, who presented as a blonde, pale-skinned woman and didn’t, in her civilian life, identify as Inuit.

Amka, however, is part of a renewed effort by Marvel to bolster its diversity, both on the page and behind the scenes. In 2015, the company launched an initiative called “All-New, All-Different Marvel,” wherein it replaced several of its most iconic white male superheroes with a more demographically representative crop of characters, many of whom are considerably younger than their predecessors and, in some cases, languished for years in supporting roles.

African American Sam Wilson, a.k.a. the Falcon, took over from Steve Rogers as Captain America. Thor’s long-time love interest, Jane Foster, proved worthy of lifting the enchanted hammer Mjolnir and became the new Thor. Korean American teenage genius Amadeus Cho replaced Bruce Banner as the new Hulk. Another teenage genius, an African American girl named Riri Williams, supplanted Tony Stark as Ironheart. And the Afro-Latino teenager Miles Morales, previously the version of Spider-Man who starred in Marvel’s “Ultimate Universe” line of comics, was integrated into the “main” universe. One of the most critically praised characters from this group is the new Ms. Marvel, a.k.a. Kamala Khan, a Pakistani American Muslim teenager living in Jersey City, New Jersey, who writes Avengers fanfic when she’s not fighting giant humanoid parakeets and the evils of gentrification in a modified swimsuit emblazoned with a vivid yellow lightning bolt.

Marvel’s efforts at diversifying have also included plenty of missteps. A series of comic-book covers inspired by famous hip hop albums was seen by many fans and critics as appropriative, given how few black writers and artists were then working at Marvel. The 2015 series Red Wolf, which had showcased covers by Jeffrey Veregge, a member of the Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe, also met with significant criticism. In a piece for the award-winning, but now sadly defunct, website ComicsAlliance, Métis critic James Leask praised Veregge’s covers but described the Red Wolf comic itself, which stars a shirtless Cheyenne man in buckskin breeches and war paint who time travels from the “Old West” to the present day, as “defining native people largely as historical ephemera and not living and vibrant people in the present day.” This series—Marvel’s first to star a Native American protagonist in over forty years—was cancelled after just six issues.

One could attribute Red Wolf’s cancellation, in part, to the problematic portrayal of its lead character. But David Gabriel, Marvel’s senior vice-president of sales, gave an interview last March in which he seemed to blame falling sales on the push for more diversity, saying he’d received feedback from comic-store retailers that readers “were turning their noses up” at diversity and “didn’t want female characters out there.” Though Gabriel quickly walked back these statements, they ignited a social-media firestorm big enough to be picked up by the New York Times and The Atlantic. On Twitter, Reddit, and other online forums, some championed Gabriel’s comments as validation of larger wars against (among other things) feminism and “political correctness”; others, including Kamala Khan’s co-creator, G. Willow Wilson, assailed their flaws, such as a failure to mention that many of Marvel’s more diverse titles, including the new Ms. Marvel series, actually sell very well and are often more popular online and in bookstores than at traditional comic-book stores.

While the theory that diversity doesn’t sell is, at best, debatable, Marvel’s commitment to diversifying does seem to have faltered. Within three years of the company’s vow to be All-New, All-Different, nearly all the characters who inherited the titles of white men have given them back: Rogers is once more Captain America, the traditional Thor is once again wielding his magic hammer, Stark is back as Iron Man, and Banner is back from the dead, in a series fittingly titled Immortal Hulk. Though the Champions series—which, in addition to Amka, stars the Amadeus Cho version of the Hulk, the Riri Williams version of Iron Man (Ironheart), the Miles Morales version of Spider-Man, and the Kamala Khan version of Ms. Marvel—proves Marvel hasn’t given up on representing diversity, it also shows how its intentions have changed. The effort is now less expansive; several female and minority characters who’d headlined their own series a year ago now only appear regularly in team books such as Champions.

Within Champions, though, the quantity and quality of diversity remains encouraging, with Amka’s creators—Canadian writer Jim Zub and South African artist Sean Izaakse—seeming to recognize the importance of representing her the right way. Early in the process of creating the character, Zub reached out to Nyla Innuksuk for advice. Originally from Igloolik and Iqaluit, Innuksuk is the founder of the Toronto-based virtual-reality production company Mixtape VR and had previously worked with other Marvel illustrators on VR projects. Innuksuk says she thinks Zub and Marvel “were hoping I would bring insight into the culture, the people, and provide some authenticity to the effort.”

It can be argued that Amka’s story doesn’t completely avoid potentially problematic stereotypes. Her transformation from a normal Inuk teenager into a magical shape-shifter is reminiscent of what Michael A. Sheyahshe, in his 2008 book Native Americans in Comic Books, calls the stereotype of the “instant shaman.” This stereotype, writes Sheyahshe, imagines all Indigenous peoples as inherently magical, while ignoring the fact that, within real Indigenous cultures, becoming a shaman “requires a lifetime of knowledge, learning, and practice.”

On the other hand, it’s significantly rebellious for a contemporary Inuk teenager to proudly become a shaman. Christian missionaries and the residential-school system forbade and demonized shamanism, and many twenty-first-century Inuit reject it. Even when it’s not condemned, it’s considered dangerous, and discussing it is generally taboo. Shamanism’s complicated legacy is evident in Amka’s initial uncertainty about traditional beliefs. Though she sports traditional tattoos on her face and hands, she doesn’t think Sila is real until she meets her and is transformed by her power.

The exuberance of this transformation resonates with increasingly vocal calls to end what Inuk writer Rachel Attituq Qitsualik calls the “code of silence” surrounding shamanism. Writes Qitsualik: “It is only through living generations acting as custodians of past knowledge—speaking the unspeakable—that Inuit culture can remain as strong as it remembers being.” According to Innuksuk, this resonance is very intentional. She says she is “fascinated by shamanism because I am the great-granddaughter of Awa, who is one of the last shamans in the Arctic. He himself had to turn away from the shamanistic tradition and join Christianity, while in Champions, we have Amka discovering those capabilities.”

Amka’s superhero costume similarly evokes both the traditional and the contemporary. As Snowguard, she wears a kind of pared-down, sportswear-inspired version of a decorative parka, rendered in sleek white with black and blue accents. Innuksuk had considerable input in the design of this costume. Says Innuksuk: “My sister-in-law, who is from Pang, Amka’s hometown, sews amazing jackets, and a lot of them incorporate contemporary design, like bomber jackets and blue-dyed seal. She, along with the young women in the Arctic who sew and put fake tattoos on their face with eyeliner, really inspired Amka’s wardrobe.” Whereas Red Wolf presented its time-transplanted protagonist as a relic from the past, Champions presents an Indigenous culture that is, just like Amka says of Pilip in her first-ever line of dialogue, very much “still here.”

We’ll have to wait to see whether Amka will connect with enough readers to become a long-term resident of the Marvel universe. What we do know is that she’s entering an industry that remains uncertain about the value of diversity and a wider world that sorely needs to see it represented well, perhaps especially in the form of heroes capable of defending both their own communities and the universe itself. And that’s plenty of reason to hope Amka will be able to do what her mother urges her to at the end of Champions #21: “Go forth.…Tell the world our story.”