Listen to an audio version of this story

For more audio from The Walrus, subscribe to AMI-audio podcasts on iTunes.

On February 25, when a photo of a For Rent sign in the window of S. W. Welch was posted on Twitter, shock spread across social media. The used bookstore, owned by Stephen Welch, had been a mainstay of Montreal’s Mile End since it relocated there, in 2007. A few years ago, a real estate firm bought Welch’s building. As Welch approached the end of his lease, which was to expire in August, his new landlord told him that the store’s monthly costs—rent, taxes, insurance, and maintenance—would go up an impossible 150 percent, to $5,000 a month. “I think they’d rather [the building] be empty than have me here,” the sixty-eight-year-old bookseller told Cult MTL.

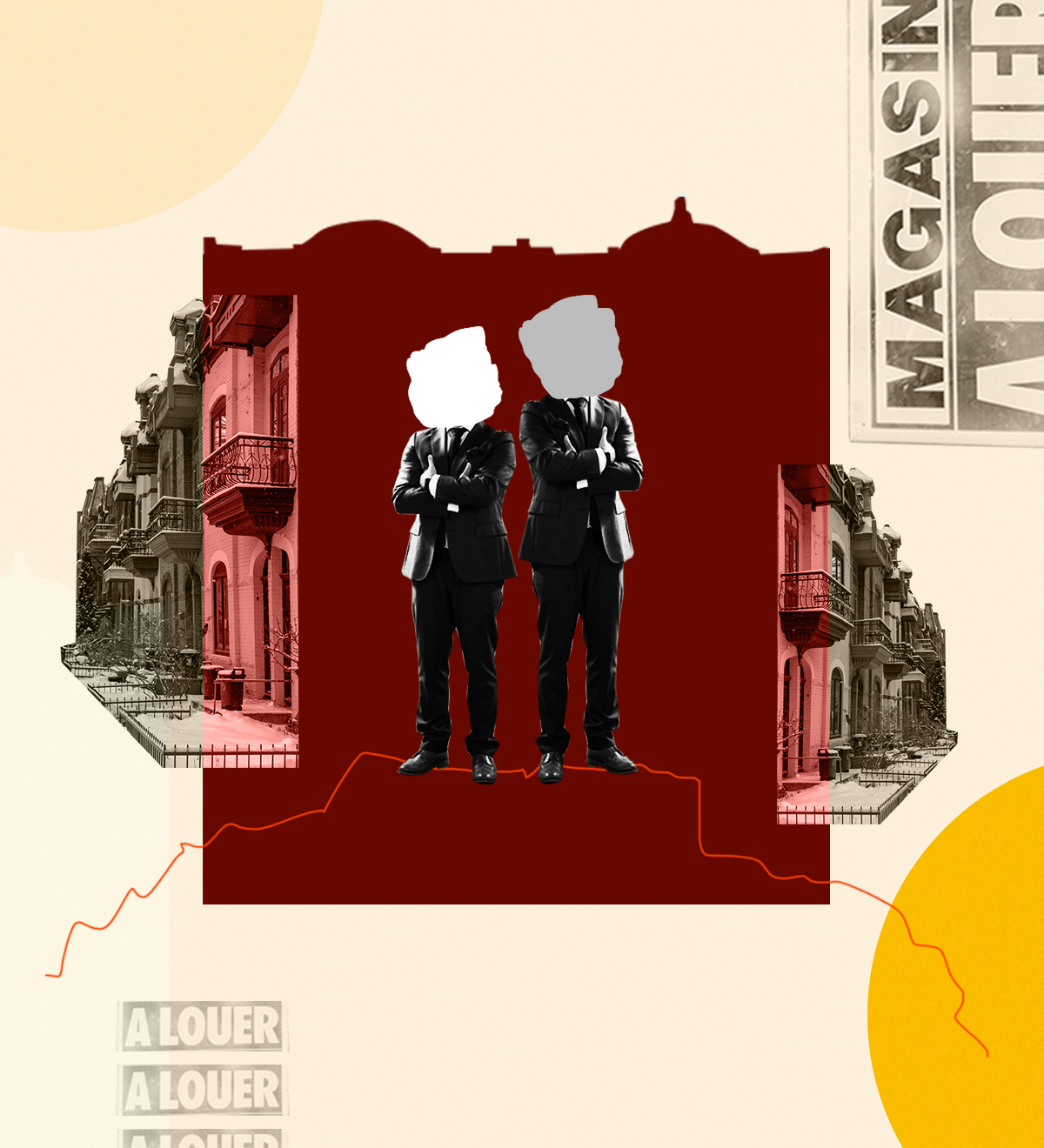

For Mile Enders, it was no surprise who was behind the shop’s ouster: Shiller Lavy. No other developer is name-checked as often in the city’s anti-gentrification graffiti; no other seems to have inspired a satirical Twitter account (called, appropriately enough, “Shitter La Vie”). Composed of Stephen Shiller and Danny Lavy, the duo is, as one activist put it to me, the “comic book villains” of Montreal real estate, notorious for buying property, hiking rents, and shoving out long-term tenants.

The centre of Montreal’s creative culture, Mile End is a pleasant jumble of stores (selling books, records, or clothes), venues, historic cafés, and bagel shops that has served as home to the city’s young and artistically inclined for decades. It is also no stranger to gentrification, with property prices driving out the very cherished establishments that made the area trendy in the first place.

Over the past few years, the neighbourhood has witnessed the disappearance of a Colombian restaurant, a thirty-five-year-old bakery, and Le Cagibi, a popular space for live music and one of the area’s last explicitly queer venues. Once these establishments are sent packing, the communities around them—sometimes built over decades—often fade away too. After closing, many storefronts were boarded up for months or even years. A healthy vacancy rate is between 4 and 10 percent, a range that accounts for renovations and normal turnover. In 2019, a consultation revealed that Montreal had hit 15 percent—in some areas, 26 percent—and that properties were sitting empty for an average of nineteen months. Testimony from community members blamed developers like Shiller Lavy for the downfall of these commercial areas. (Shiller Lavy did not respond to requests for comment.)

Discontent about vacancies had been building for years. But it was Shiller Lavy’s cavalier attitude that ultimately provided the catalyst for action. Speaking to the Montreal Gazette in early March, Daniel Lavy scoffed at the store: “Does anybody buy books today?” The community response was immediate. Activists formed the anti-gentrification group Mile End Ensemble and mobilized a book-buying protest. Days before the event, Shiller Lavy backed down, renewing Welch’s lease for two more years. “I went up a little,” Welch posted on the shop’s Facebook page, “and he went down a lot.” The protest went ahead regardless—a David-over-Goliath victory at the end of a punishing winter.

Shiller Lavy is an irresistible flashpoint for Montreal’s gentrification frustration, but it is not the sole reason commercial spaces are disappearing. The city also bears some of the blame. Its situation is by no means unique—New York, Toronto, Vancouver, Calgary, and Winnipeg are just some of the urban centres in North America that have also fallen prey to ballooning rents and little-to-no regulatory oversight. While the enthusiasm of activists celebrating Welch’s victory was palpable, citizens alone cannot stop once-vibrant streets turning into developer-created ghost towns. Cities need to do their part too.

To many, it makes no sense to leave a building vacant. Shouldn’t a landlord prefer rental income to nothing at all? “There are many ways to generate profit from commercial properties,” says Glenn Castanheira, executive director of a downtown Montreal business association. “Rent is only one of them.” Another way is speculation: wealthy players buy property because its value is on the rise or soon will be. Once it’s worth a hefty chunk, the property is either sold or rented to a deep-pocketed tenant (often a chain) willing to pay an inflated cost. If no buyer or tenant arrives quickly, waiting it out is usually the appealing choice for landlords able to absorb losses as part of an extensive real estate portfolio.

Unfortunately, municipal laws don’t prevent real estate speculation. This is why “we see some dramatic cases of abuse,” according to Castanheira. “Say a landlord buys a property with a mom-and-pop shop that pays its rent on time every month, but only pays $1,000. The landlord may think he can get $5,000 or $10,000 per month,” Castanheira explains. “Even if the property remains vacant for ten months, it only takes one month’s rent with the new tenant to make back what they lost.” Commercial leases are long, usually five to ten years or more, so for many landlords, it’s worth holding out for the big return. And, with no rental regulation for commercial tenants, there is nothing to stop landlords increasing prices at will.

Other landlords, however, also bristle at empty storefronts. A report published last year by the Winnipeg Department of City Planning found that some developers accuse absentee owners of “[devaluing] not only their own properties, but adjacent properties too.” When Montreal carried out its consultation, among the respondents were small landlords who blamed larger development companies for mass purchasing property and then destroying the neighbourhood’s character with vacancies.

Castanheira believes that, even if only a small minority of landlords are leaving spaces empty through speculation, their outsize impact on a community is worth legislating against. Municipal inaction is what drove Toronto city councillor Brad Bradford to advocate for a vacancy tax: a penalty applied to properties that sit dormant for a year or more. “Main streets are for people, not speculators,” says Bradford, whose constituents in Beaches–East York are frustrated by the state of retail vacancies—many of them, he says, lasting for more than a decade. “If a storefront is sitting empty, not of necessity but simply because an owner has the long-term holding power, that’s unfair.”

Bradford brought a vacancy tax to the council in early 2020. Similar measures were put forward at roughly the same time in other areas, including New York, Boston, and Montreal. But many of these efforts are on hold while cities grapple with the impact of the pandemic on their budgets. A vacancy tax sounds like an easy balm to the problem of chronically vacant storefronts, but counterintuitively, cities have instead often given tax rebates to the owners of vacant property. Until recently, Ontario mandated a flat 30 percent tax break to owners whose buildings had been empty for at least ninety days, with no maximum time limit. It was a measure born of the ’90s recession, intended to help ease the effects of economic downturn and falling property values.

While vacancy rebates provided some businesses with a needed reprieve in fiscally difficult times, they were criticized for, in Bradford’s words, “incentivizing owners to keep stores empty while they waited for values to get high enough for redevelopment.” A review ordered by the Ministry of Finance showed that the policy had exacerbated the issue of “chronically vacant” street-level commercial real estate. A well-meaning initiative to help struggling property owners had been thoroughly negated through exploitation and speculation.

One immediate way to address our vacant storefront problem is to simply fill them. Pop-ups, or the use of empty commercial spaces for short-term purposes, allow businesses to test the viability of their models while providing landlords with some limited rent. For years, they have been an option for retailers from tiny online Etsy brands to established names like IKEA looking to test the waters in new territory. Toronto’s Pop-up Shop Project, led by a community organization, claims to have helped cut commercial vacancies in the Danforth East area by 64 percent in its first four years.

But pop-ups don’t have to be primarily commercial. They can also be used to claim empty storefronts for short-term community endeavours facilitated by city officials. Jim Morrow, an environmental sociologist at the University of Alberta, is one of the authors of “A Field Guide for Activating Space,” part manifesto, part informational pamphlet about the glut of vacant urban properties that “burden communities with blight and cost.” Empty storefronts are known to reduce a sense of community and engagement in an area, but their risks are also straightforwardly measurable: vacant properties are linked to increased occurrences of fire, crime, and injury. Morrow and his co-author see these empty spaces, left to rot by owners and city management alike, as a civic failure, a sign that “conventional approaches to development no longer work” and the time has come to try something else. As he put it, “Why not just use them?”

Socially enriching pop-ups require changing the role of city planners from people who primarily deal with developers to conduits between city administration and the public. If, for instance, you wanted to put on a weekend of live music or open up a seasonal restaurant project for a month, you’d need a space with the appropriate noise permits, electrical hook-ups, and physical layout. That is where city planners could come in. According to Morrow, empty spaces with these facilities exist all over cities, but it’s inordinately difficult for the average person to access them. “City planners know more about buildings than anybody else,” he says. By keeping detailed registries of empty properties, city planners could easily match up vacant buildings with willing partners.

In his hometown of Edmonton, Morrow says, community groups recently persuaded city council to hand over an abandoned storefront to a temporary women’s shelter. He also knows of a formerly vacant storefront in Fort Morgan, Colorado, that became a community centre for the town’s rapidly increasing immigrant population. “Reusing these public spaces creates sites of connection,” Morrow tells me. “It seems really small, but it builds up over time.” Having people occupy these spaces also keeps them lively, preventing a neighbourhood’s slide into neglect and disarray.

Pop-ups, of course, don’t stop gentrification. Communities have good reasons to be suspicious of the revitalization of neglected areas—it’s often a precursor to displacement, a sign that a working-class old guard is being pushed out. Critics also note that the short-term relief pop-ups provide isn’t a replacement for real municipal investment into public services: pop-ups might bring engagement to an area, but so do swimming pools, public transit, libraries, and parks. Morrow understands these concerns but believes the reality of decaying public spaces is too urgent to wait. “Temporary use should not be a long-term solution,” he says. “It’s how we get to something better.”

Welch has posted on Facebook that, when his lease is up in two years, he intends to retire. There is no guarantee, however, that he won’t be replaced by a chain store—or even that a new tenant will appear in a timely fashion. There are numerous challenges facing our city streets, particularly in a post-COVID-19 world. A recent report from the Canadian Federation of Independent Business stated that up to one in six businesses are at risk of closing, in large part due to the pandemic. Many of us have already seen favourite restaurants and bars disappear over the past year. Without regulation and municipal intervention, developers will be free to run roughshod over the landscape.

Even as the Mile End bookstore debacle died down, another neighbourhood came under threat: Stephen Shiller’s son, Brandon, recently purchased large swaths of property in Montreal’s Chinatown, prompting concerns about the possible erasure of a valued cultural space. Local organizers are seeking heritage protection to conserve the area, but some fear it is too late. While they embark on the slow process of lobbying officials and filling out preservation paperwork, developers are free to plow forward with their plans, unencumbered by community concerns or regulatory restraints.

For Patricia Boushel, a Mile End Ensemble activist, the time has come for cities and developers to start listening to the people living in the communities affected by the constant instability. “People are tired,” she says. “They want to take control of what their neighbourhoods look like.”