Late one night in 1968, Jimi Hendrix, Joni Mitchell, and William Hawkins sat, cross-legged and likely stoned, in an Ottawa motel room. Hendrix and Mitchell had both played gigs in town earlier that night, and Hawkins, a long-standing member of the local coffee-house scene, had brought his guitar to the after-party. He played them a song he’d written called “Scorpio.” Mitchell was born under that sign, and as Hawkins later admitted to the Ottawa Citizen, he had been “trying desperately” to seduce the celebrated folk singer for years. “That night she looked so radiant and was smiling a lot.” Hawkins told Hendrix he’d written a song for every zodiac sign because it was a good way to pick up women. Hendrix laughed out loud. “He laughed even louder when I told him it wasn’t working on Joni,” Hawkins said.

I’ve read a few different accounts of that night, and in my favourite, singer Ritchie Havens was at the motel too. The next year, in the summer of 1969, Havens performed a fearless opening set at Woodstock in front of tens of thousands of fans. But, at the motel, the charismatic twenty-seven-year-old from Ottawa was almost too much for Havens. According to Hawkins, Havens looked at him and said, “I don’t know if the world’s ready for you, man.”

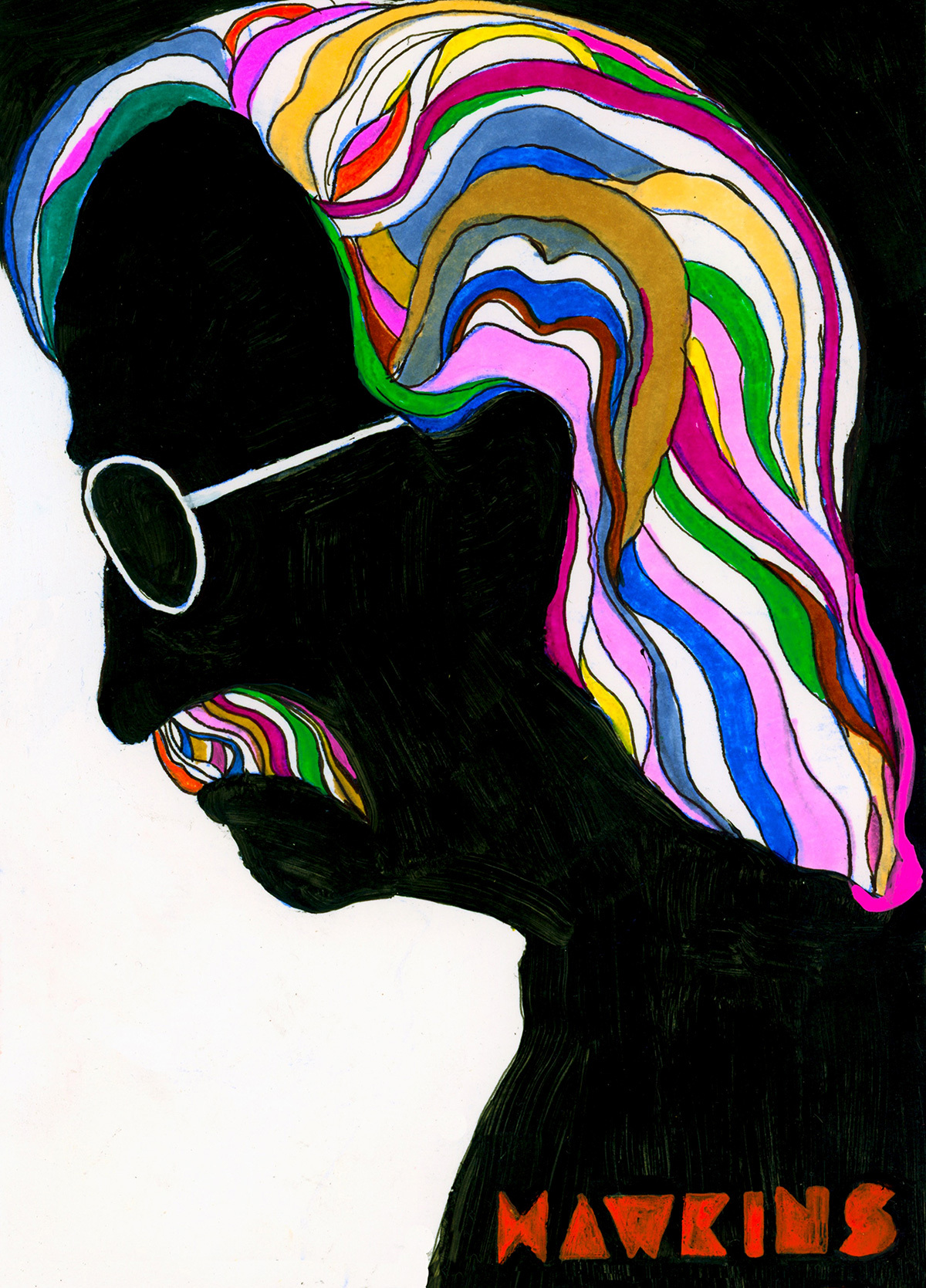

I first heard of William Hawkins—or Bill, as he was known—in 2019, when I was working on a book about taxi drivers with remarkable life stories. Hawkins’s biography certainly qualified. Called “Canada’s own Bob Dylan” by the Citizen in 1966, Hawkins lived dangerously. He “took drugs, drank too much, insulted important people,” wrote his friend, novelist and former book publisher Roy MacSkimming. “In fact, he insulted most people, important or not, more or less on principle.” But Hawkins didn’t just raise hell. He made art. Even in a period well-known for maverick personalities, Hawkins stood out. It’s no surprise that musicians and poets were drawn into his orbit. Relentlessly inventive, he helped forge a cultural scene in a stuffy government town the 1960s might otherwise have overlooked—that is, until he fled that scene, in the 1970s, and spent the next three decades driving a taxi.

As it turned out, I’d discovered him too late. Hawkins passed away in 2016. I never had a chance to meet him. But, the more I learned about him—reading the stories, speaking to friends and collaborators about his outrageous adventures, poring over his poems — the more I realized that Havens had a point. In the first half of his life, before he found himself in the driver’s seat of an Ottawa cab, Bill Hawkins was an undeniable force, both creative and destructive. The world might not have been ready for him. But that same world now seemed diminished by his departure.

Mackskimming was home for the summer from his first year at the University of Toronto, in 1963, when Hawkins called. MacSkimming had met Hawkins a year earlier, at the Studio Club, a building slated for demolition that housed studios for Ottawa’s oddball artists. Hawkins’s first published poems appeared on woodcut posters he and his Studio Club friends created, which he often sold for twenty-five cents or stapled, guerilla-style, to telephone poles around the city. MacSkimming, eighteen years old at the time, had just finished high school and hardly fit into Studio Club’s counterculture scene. He had captained the football team and served as editor of the yearbook. By then, MacSkimming had already discovered the poetry of Irving Layton and Leonard Cohen and had started writing his own. “I was an aspiring bohemian,” he says. His fledgling poetry attracted the attention of an Ottawa radio DJ who hosted a midnight show featuring classical music and poetry readings. The DJ connected MacSkimming to Hawkins, and the two poets met in the Studio Club’s unlicensed bar. “I hadn’t begun to drink in those days,” MacSkimming says. “Bill soon helped with that.”

“Have you heard about this poetry conference at UBC?” Hawkins asked over the phone. MacSkimming hadn’t. The University of British Columbia had invited a number of American poets to lead an intensive three-week summer program that included workshops, lectures, and readings.

“Allen Ginsberg and Robert Creeley are going to be there. We need to go.”

“Who is Creeley?” MacSkimming asked.

“I don’t know, but we’ll find out. We have to go.”

“We do?”

“When else are you going to meet Allen Ginsberg?”

MacSkimming and Hawkins applied for the conference, and both were accepted on the strength of their submitted poetry. All Hawkins needed was tuition money. So he held an event called Help Get Hawkins Out of Town at Café Le Hibou.

If Hawkins was the high priest of Ottawa’s beatnik underground, Le Hibou was the scene’s cathedral. Everyone played Le Hibou in the 1960s and ’70s, from musicians Ian and Sylvia Tyson, Buffy Sainte-Marie, and Gordon Lightfoot to comedians Rich Little and Dave Broadfoot. Irving Layton read his poetry there, and an attendee claimed that George Harrison once visited disguised in sunglasses and a Boy Scout hat. Much of what I’ve learned about Hawkins comes from Ken Rockburn’s excellent history of the coffee house, We Are As the Times Are: The Story of Café Le Hibou. Rockburn devotes an entire chapter to Hawkins, called “The Ringmaster,” and the book’s title comes from a song Hawkins wrote.

Hawkins held court at Le Hibou. He was also sometimes on staff. He and his wife, Sheila, opened and closed the doors, worked the kitchen, and tended to the visiting performers. Even after Hawkins stopped working there, he remained as permanent a fixture as the Chianti bottle candle holders and the coffee mill that, according to Rockburn, he once used to grind hallucinogenic morning glory seeds.

MacSkimming and Hawkins both read poetry for the tuition fundraiser, and a shy kid named Bruce Cockburn played classical guitar. Money raised, the duo pointed MacSkimming’s convertible west for their seven-day odyssey. They camped every night, sometimes in provincial parks, sometimes at the side of the road, once on the edge of a cemetery in Swift Current, Saskatchewan. They cooked over campfires or ate greasy burgers in cheap small-town diners. The pair had to cover hundreds of kilometres each day in order to reach Vancouver in time for the conference. Hawkins filled their highway hours by reciting poetry from memory: Dylan Thomas, W. H. Auden, John Keats. When he grew weary of poetry, Hawkins sang songs and told stories. MacSkimming learned about Hawkins’s father, a car salesman and a violent drinker. Hawkins talked about his mother and about his grandmother, from whom he had inherited his love of literature. “She read everything,” he would tell a reporter in 1997. “She had this broad exciting imagination and she made me see the world of books and writing.”

Hawkins also told MacSkimming about his job as a newspaper copy boy, where he’d learned the basics of writing. (In another interview, Hawkins admitted he was such a poor reporter that his editor had suggested he stick to poetry.) Hawkins also spoke about his brief stint in jail for what MacSkimming remembers as “some misdemeanour involving other people’s cars.” While the details differ from retelling to retelling, Rockburn’s book has what seems the clearest version: after a long night out in Gatineau, Quebec, Hawkins was approached by police while trying to steal a car to drive back home. When Hawkins stepped out of the car, he grabbed at an officer’s gun. The stunt landed him behind bars for about two weeks, long enough to acquire a prison tattoo—a pattern of bluish dots on the web of his left hand.

MacSkimming’s car broke down beside the Blackfoot reserve near Gleichen, Alberta, and barely crested the Rockies, but the pair eventually arrived at UBC. They spent three weeks living and working with their fellow poets and faculty. Not only did Robert Creeley, then a major figure in American poetry, have a profound influence on Hawkins’s writing, but when the car broke down again on their way home, Creeley came to their rescue. “He materialized over breakfast in a Chinese café,” MacSkimming later wrote, “and paid the mechanic’s bill we couldn’t afford.”

The time at UBC sparked Hawkins’s poetry career. He published five collections in the seven years following his West Coast sojourn — including a chapbook he produced with MacSkimming called Shoot Low Sheriff, They’re Riding Shetland Ponies. Hawkins’s poetry also appeared in two groundbreaking national anthologies, alongside work by Margaret Atwood and Michael Ondaatje. An early poem called “Porsche” captures some of Hawkins’s hellraising spirit:

If I had me a Porsche

A black sleek animal Porsche

I’d find me a brick wall

With two miles of road in front of it

and

BANG

me and the Porsche would swing out

In 1966, his literary activities caught the attention of an Ottawa youth group that declared Hawkins—along with a town planner and an Ottawa Rough Riders quarterback—a winner of the Outstanding Young Men award. The photo in the paper shows Hawkins in a smart suit and wire-rimmed glasses, sporting a horseshoe moustache and holding a commemorative plaque, posing with guest speaker senator Ross Macdonald. The photo does not show Hawkins’s prison tat. The fact that Ottawa’s patron saint of counterculture could win such a mainstream, milquetoast honour probably amused everyone who knew him—and, eventually, Hawkins would use the plaque as a cutting board for hash.

Around the time of the award, Hawkins helped start a band called The Children. “In Canada one can’t expect to live by poetry,” he explained to the Citizen. “It’s a doomed art form. That’s why so many poets are turning to the music industry.” The Children featured some of Ottawa’s best folk musicians, including Bruce Cockburn, whose skills on the guitar were already well-known. Cockburn rented a room on the second floor of Hawkins and Sheila’s house, long a hangout for wild friends and visiting musicians. “Hawkins’s living room was a convergence point for all sorts of stuff,” Cockburn tells me on the phone from his home, in San Francisco. “Sometimes it was the people playing Le Hibou. Sometimes it was people passing through. It was an interesting household. And a difficult time for Sheila, Bill’s wife. Had to look after all these men plus their two little kids.”

Hawkins acted as The Children’s creative catalyst. “He was the brains of the gang,” Cockburn says, “lurking in the background rather than performing with us.” He penned raw, beautifully dark songs, and Cockburn started writing music to pair with Hawkins’s words. “He had a keen appreciation of good songwriting,” Cockburn says, “and a very well-developed appreciation of poetics. And, you know, I remember listening to whatever the latest Dylan album was and Hawkins going, ‘Oh, that was a really great line.’ And, a few lines later, saying, ‘Oh, he should’ve never written that one.’ It wasn’t like he was putting himself in any godlike position. He was just reacting in a critical way out of his knowledge of language.”

Cockburn wonders if simply spending time in Hawkins’s presence was one of the most valuable experiences of all. “Perhaps more so than the songwriting itself,” he says. “He just had this way of hearing.” What Cockburn learned in that living room more than fifty years ago remains part of his approach to writing music. “For me, he was a mentor,” Cockburn says.

But Hawkins had more to offer than his poetic sensibilities. He was about five years older than everyone else in the band. Those extra years of life, recalls Cockburn, gave him a unique perspective. He’d travelled more than any of them. He’d caroused with Ginsberg. He’d endured the violence of an abusive father, and he’d been to prison. Hawkins rarely boasted about these things, nor did he express much shame. Cockburn remembers the first time he saw Hawkins’s prison tattoo. “He was semi-proud of that,” Cockburn says. “When he talked about that, it was with a mixture of ruefulness and pride.”

The Children quickly became a beloved Ottawa band. They opened for Gordon Lightfoot and The Beach Boys and, later, for The Lovin’ Spoonful at Toronto’s Maple Leaf Gardens. Cockburn recalls Hawkins sitting on the Gardens’ stage in a wooden rocking chair, reading a book while the band played, “like the éminence grise that he was.” In Rockburn’s book, however, Hawkins insists he sang at least one song that night, something he’d never done before. Hawkins felt uncomfortable when the house lights went up to reveal a crowd of screaming kids in their mid-teens. “I was twice their age,” he told Songwriters Magazine years later. “I turned to Bruce as we walked off stage and said, ‘I’m finished.’” So was the band. After only two years together, The Children broke up.

The end of The Children, in 1967, marked the beginning of a darker time for Hawkins. “All my troubles started when I left the stage,” he told a reporter. His drinking and drug use accelerated. So did his womanizing. Hawkins was never alone in his self-destruction; everyone wanted to hang with him. According to MacSkimming, Hawkins took acid with Leonard Cohen in Montreal. On one memorable night, Hawkins told the Citizen in 1997, he and a cohort of musicians “got into more trouble in six hours than most people could get into in six years.” After a while, even Hawkins knew he was out of control.

In the late ’60s, Hawkins saw a chance at salvation in the form of free government money. The Canada Council for the Arts awarded him a $3,500 bursary to write poetry. Reasoning that the money would last longer in Mexico, he drove Sheila and their two young children south. He and Sheila both felt that being away from the Ottawa scene might help straighten him out. They miscalculated. “I thought I’d go down there to get my strength back, that’s how screwed up I was,” Hawkins told the Citizen. “I mean, beer was like, eight cents a litre, tequila was eight cents a glass and you could walk into a pharmacy and say ‘Could I have a quarter-grain of heroin, please?’ and they would give it to you. A guy like me was not going to get healthy there.”

He didn’t. According to Rockburn’s book, Sheila and the kids headed home after a few weeks, leaving Hawkins to his demons and devices. Hawkins stayed in Mexico for anywhere from six to eight months. He later claimed he managed to finish only one poem, adding with a smirk that the Canada Council had never told him how many he was supposed to write. In truth, he filled his notebook with short poems, poetry fragments, scribbles, and drawings. “The notebook contained powerful glimpses into his evidently harrowing time in Mexico,” MacSkimming says. “A record of what may have been alcohol-and-drug-induced hallucinations and paranoia.”

The notebook was not Hawkins’s only Mexican souvenir. Legend says he also used the grant money to buy marijuana, which he smuggled into the US. Once again, the most gripping version of this story can be found in Rockburn’s book. Hawkins and two co-conspirators placed sixty-eight kilograms of weed on their heads and waded across the freezing neck-deep waters of the Rio Grande into Texas. Waiting for them was a contact who picked them up in a truck and headed up the highway toward Denver. But they soon came upon a roadblock. Hawkins pulled a Walther .38 out of his pocket, turned to his friend, and said, “I’m not going to jail in Texas.” He rolled down the window, the gun in his lap, and said, “I’m going to shoot these sons of bitches.”

An officer approached the car. “You boys all American citizens?”

“Yes, sir!” Hawkins said.

“Well, you all go on through then.” The officer wasn’t looking for drugs; he was looking for migrants. The men drove on to a Denver motel, where they packaged the marijuana.

It’s hard to say how much of this is true. But the mythmaking didn’t stop there. The next stage of the plan involved ferrying the weed across the border to Toronto. According to one account, Hawkins found someone to paddle a canoe across Lake Ontario to a rendezvous point on the American side, about a fifty kilometre trip. Hawkins and his crew would lash the plastic-wrapped dope to the bottom of the canoe. Then, after dark, the friend would paddle the load into Canada, to another prearranged site. The entire scene—sixty-eight kilos of weed purchased with a Canada Council grant being ferried across Lake Ontario in a canoe to evade the RCMP—was one Timbit shy of a Heritage Minute.

Hawkins’s eventual path across the border was considerably less maple dipped. At the last minute, a sympathetic reverend Hawkins knew in Denver offered to drive the contraband across in his van. The reverend pulled up to the customs post and told the border guard he was headed to the Canadian Tulip Festival. He was promptly waved through.

At some point in the early ’70s, Hawkins woke up in the Donwood Institute, a Toronto rehab centre. He had no idea how he’d arrived there. (MacSkimming believes he checked himself in.) The first thing he did was ask his nurse for a large glass of whisky. She refused. As he later revealed in an interview, his chart showed blood levels of alcohol, heroin, and “a bunch of pills.” Hawkins was also suffering from acute malnutrition. According to one source, the drugs and liquor had whittled his six-foot frame down to as little as 128 pounds. “I was what they called a ‘crossaddicted personality,’” he says in Rockburn’s book, saddled with dependencies to both alcohol and heroin.

Hawkins emerged from Donwood clean and sober after twenty-eight days. Roughly a year later, he started driving cab. “The cab was a perfect way to hide out,” he once said. “Nobody knew where you were. It kept the temptations away.” He called it his “outlaw existence.” I found this ironic: Hawkins had been a prison inmate, a poet, a musician, a drug user, and if the stories are true, a drug smuggler. But only after he started driving a taxi did he consider himself an outlaw.

As a cabbie, Hawkins abruptly switched from cavorting with bohemian rule breakers to serving the capital’s lawmakers. According to MacSkimming, Hawkins’s clientele included members of Parliament, provincial judges, political staffers, and members of the press gallery. “He felt quite able to hold his own as an equal with a famous national columnist or a cabinet minister or an opposition member,” MacSkimming says. And he was always learning. “He had very sharp ears and would pick up a lot of scuttlebutt. He could, on occasion, be a source of information.” If the reporters who were among his regular passengers wanted intel about a potential early election call, Hawkins might know.

Hawkins enjoyed a revival during the final decade of his life, in the mid-2000s, as he emerged from his taxi hideout and returned to both poetry and music. Sharp eyes had already spotted him driving a cab in Ottawa for years. “Stories of seeing Bill became as rich and plentiful as tales of the Loch Ness Monster,” poet Rob McLennan once wrote. Still, Hawkins’s relaunch into the city’s art scene surprised many. The Citizen, covering the release of 2005’s Dancing Alone: Selected Poems, ran a two-page profile of Hawkins that began with the line: “William Hawkins is not dead.”

Cockburn wrote the preface to Dancing Alone, and he and Hawkins reconnected briefly for the first time in decades. “He had been through the ringer,” Cockburn tells me. “By that time, he’d been a junkie and got off dope and had his life under control.” But Cockburn noticed something else different about Hawkins. “He was a gruff and grumpy guy when The Children were going. Not all the time but a lot of the time.” Hawkins could be abrasive. He resisted getting close to people. Not anymore. “That vibe was kind of gone,” Cockburn says. “I think he liked hanging out and he liked conversations with people. . . . He was a warmer-seeming individual with a kind of greater capacity for laughter, including at himself.”

Hawkins’s renaissance continued with the 2008 release of the double album Dancing Alone: Songs of Bill Hawkins. Cockburn performs one of the twenty-four songs on the tribute record, as do a dozen more Canadian musicians. On the first track, Lynn Miles covers “Scorpio,” the song Hawkins sang for Joni Mitchell in that motel room forty years earlier. A collection of Hawkins’s lost poems titled Sweet & Sour Nothings came out in 2010, alongside Wm Hawkins Folio, a catalogue of his work. Time Capsule: The Unreleased 1960s Masters, an album of live and demo music by The Children, appeared in 2013. That same year, Verse Ottawa, a collective of local poetry groups, inducted Hawkins as the first member of its hall of honour.

In 2015, an Ontario publisher released The Collected Poems of Bill Hawkins. Hawkins read from the book for the launch party at Ottawa’s Manx Pub. In a video of the event posted on YouTube, he looks thin. Oxygen tubes run around his ears and in front of the turtleneck he wore under a brown sports coat. Hawkins apologizes for being less prepared than his fellow readers that night. “I didn’t even know I was coming until three o’clock this afternoon,” he says. “This is one of the problems of being old and sick. And a dinosaur.” In spite of this, Hawkins recites most of his poems by memory, only rarely peeking down at the book in his hand.

Hawkins died a year later, in July 2016. Though he’d long suffered respiratory problems, it was colon cancer that finally claimed him. “He spent a short time in the hospital,” poet Cameron Anstee wrote on his blog the next day, “and his passing was both a surprise and not a surprise — it was expected but not expected quite so soon.”

Several months before the book launch, Hawkins admitted to the CBC’s Alan Neal that, among his “many failures in life,” he had been a “cheap gambler” with his talent. When Neal asked what had made him gamble, Hawkins quoted from memory part of a poem his grandmother used to read him, Robert Service’s “To the Man of the High North”:

The Here, the Now, the vast Forlorn around us;

The gold-delirium, the ferine strife;

The lusts that lure us on, the hates that hound us;

Our red rags in the patch-work quilt of Life.

Even though I never met Hawkins, I want to think I understand what he meant by this poetic explanation of his failures. He seemed to be saying that he’d anted up his talents on crazed quests for the “gold” of the day — drugs and sex. All those feral pleasures and rage left him in rags. But Hawkins did not recite the end of Service’s poem for Neal. This is unfortunate, because those final lines grant him a kind of redemption:

These I will sing, and if one of you linger

Over my pages in the Long, Long Night,

And on some lone line lay a calloused finger,

Saying: “It’s human-true — it hits me right”;

Then I will count this loving toil well spent;

Then I will dream awhile — content, content.