Almost invariably, when a soldier first returns from a long overseas deployment, things are cheery and positive. After being away from family, dealing with distressing events, experiencing intense culture shock, and lacking many creature comforts, soldiers are happy just to be home. Health concerns, especially mental ones, usually fall pretty low on the priority list. Some soldiers with mental-health problems crash shortly after this honeymoon phase is over, but I was able to get back into a routine relatively quickly.

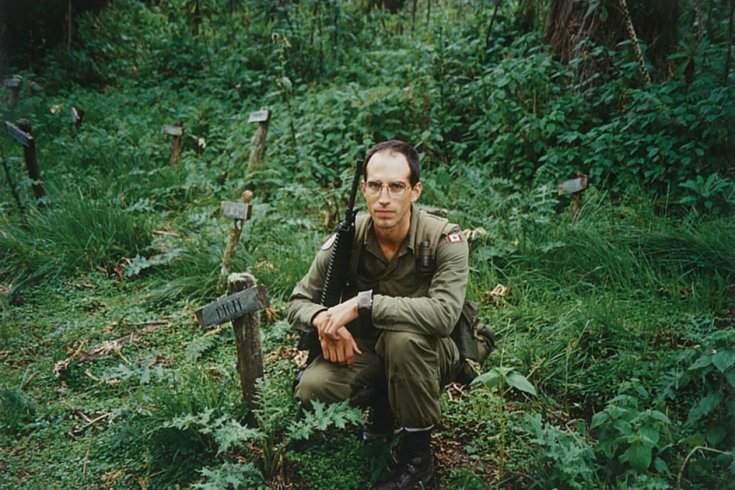

And yet, shortly after I returned from Rwanda, I started to change. It wasn’t any single event that signalled this transition, but rather various subtle shifts that, in retrospect, acted as signs of things to come. One day in April, shortly after I resumed my job as a media-liaison officer, I received a call from the military logistics staff telling me my equipment from Rwanda had arrived in Ottawa. I promptly drove to the airport, signed for it, and brought it back home.

The following weekend was unusually sunny and warm, so I decided to open up my barracks boxes and equipment bags and clean and sort through things in the driveway. As I began my work, my daughter Veronique was happily taking advantage of the good weather to ride her tricycle around on our dead-end street. After watching her enjoy herself for a few minutes, I opened everything up, attached the hose, and began by cleaning my boots. I picked one up and began spraying the sole, which still had Rwandan soil stuck in it. Just then, Veronique started walking up the driveway with a curious look on her face, to see what I was doing.

With the juxtaposition of these two sights—my daughter approaching while the red soil washed down the driveway—I suddenly panicked. The idea of my daughter and the Rwandan soil being in close proximity to each other symbolized the coming together of two worlds that had to be kept apart; I was horrified at the thought of my daughter getting even a drop of that tainted soil on her. I reacted without thinking, curtly telling her to get back on her tricycle and go up toward the house.

I was so focused on spraying those boots and washing away all that red soil—an act of symbolic cleansing—that the gentle father in me had momentarily fled. In another state of mind, I would’ve been much kinder, would’ve just picked Veronique up, put her back on her tricycle, and sent her on her way. Outwardly, the event wasn’t anything intensely dramatic: anyone watching might have just thought I was in a bad mood. But, inwardly, a chasm was already forming between me and the “normal” people around me. Together with other similar events, this incident demonstrated that I was sliding toward a mental break. The problem was that I just wasn’t watching out for it.

The nights became increasingly difficult. I was very restless, had many nightmares. Days weren’t much better. Julie noticed me becoming increasingly impatient, flying off the handle over slight inconveniences. I was also very confused. Where, I wondered, did these feelings originate? Did the lack of sleep lead to nightmares, or did the nightmares lead to lack of sleep? Where did Rwanda fit into all of this? Was this just a temporary rough patch? Even in retrospect, it’s tough to sort out. But one thing was clear: I was gradually being altered.

As the fall approached, things became extremely hectic at National Defence headquarters. The Belgian government was coming down very hard on General Roméo Dallaire for the death of ten of their soldiers under his command in Rwanda and wanted him brought to Europe for questioning. The UN refused to send him. My bosses at NDHQ were asked to help, and since I’d served under Dallaire in Rwanda, I was sent to Montreal along with two others to help him with his response to the Belgian government’s questions.

I was working a lot of evenings, but one day, I decided to go home for dinner; I’d have to return and finish up later on, but a bit of time with my family seemed like a welcome respite. My mind felt like it was operating normally.

But then, on my way back after a nice meal with Julie and the kids, I was coming down a hill near the University of Quebec. As the car built up speed, I thought, “I’m going to wrap my car around a pole. I’m done.” The idea came in a flash. I had never even thought of the word suicide before—it just wasn’t in my vocabulary. It was then that the gravity of the situation hit home. I thought, “What the hell am I doing?” Just as suddenly, the thought vanished.

I tried to put this scare out of my mind, and I didn’t tell Julie about it when I got home later that night. But the next morning, as I put on my uniform and prepared to head back to work, I was consumed by thoughts of what might have happened. I had a beautiful wife, two great kids, and a good job. Everything seemed fine. I just couldn’t figure out what was wrong. And so, instead of going to work, I went to the National Defence Medical Centre in Ottawa.

It wasn’t the norm at that time for a soldier to seek medical attention for mental-health issues so soon after a deployment. It was when I got to the parking lot that when stigmas about mental illness—which many soldiers still feel—started to kick in. I knew that, when I went inside, they were going to ask me to fill out a form with my reason for visiting. As I thought about the previous night, I didn’t know what I should write. I felt embarrassed. The person behind the front desk was usually a junior non-commissioned officer. I didn’t have a big ego, but as a captain, the thought of disclosing the fact that I was suicidal to a corporal was slightly humiliating. I sat in the car for about fifteen minutes.

As I expected, a master corporal greeted me at the front desk. I filled out the form he gave me but left the “reason for visit” box blank. When I returned the form, the corporal quickly scanned it and told me I needed to write in why I was there. I said that it was difficult to explain, that I just wanted to speak with a doctor. He politely repeated his request. My style of command was never based on bullying or browbeating my subordinates, but at that moment, I glared. “If you don’t let me see a doctor without filling out this damned sheet of paper,” I told him, “you’re going to see me back here in a body bag.”

Taken aback by my response, the corporal understood it was necessary to sidestep protocol. The whole waiting room had, of course, heard my outburst, and as I went to find a seat, I felt embarrassed. I picked up a magazine and did my best to cover my face, but I knew those waiting were probably wondering what was wrong with me. I now felt another kind of shame—not just because I was asking for help but for dressing down that poor corporal in front of the whole room. Minutes seemed like hours as I stared blankly at the magazine, waiting for my name to be called.

The doctor listened attentively as I explained my situation, and because of her calm, gentle demeanour, I felt confident that she’d be able to fix me right up. But, after about ten minutes, she told me that she suspected I might have what she called “PTSD.” Although I’d heard that term in passing a few times, I had no idea what it meant. She concluded our appointment by saying that my malady was beyond her expertise and that she was referring me to a specialist. A week later, I had an appointment with a military psychiatrist.

I saw that psychiatrist three or four times over the course of a few weeks. All I can remember from my first session with him are very in-depth, if somewhat mundane, analytical questions: “How’s your life? Do you have any debts? What was your childhood like?” It sounded like something from a Woody Allen movie, and I felt it didn’t really get to the heart of anything. I was a veteran of Rwanda, a country that had seen some of the worst atrocities since the Second World War, and all he could ask me about was my childhood. I had greater concerns, like figuring out what was keeping me up at night and why I flipped out on my daughter that day in the driveway.

I left feeling disillusioned. But I understood that Rome wasn’t built in a day, as the saying goes, so I decided to allow time for the process to work. But the second appointment was the same, and then the third, and eventually I was prescribed a bunch of pills. At that point, I was tempted to give up. Right from the get-go, there was no “therapeutic alliance”—no connection between us. I was just another patient being given the one-size-fits-all remedy of talk therapy and pills. He might have been a competent clinician, but he appeared to have no people skills and didn’t understand how to get to the root of what troubled me. We weren’t talking about what I thought was disturbing me; instead, we were talking about what he wanted to discuss. I went home with very little understanding of even what the pills he prescribed were for. Simply put, I had no confidence in him or his ability to help me. Later, I flushed the pills down the toilet.

Like numerous soldiers during the 1990s, I’d come into contact with a dysfunctional military health care system and stale psychiatric methods, not to mention many doctors who were unaware of what war and peacekeeping could do to a person’s mind. The military was completely unprepared to deal with the aftermath of sending thousands of people on peacekeeping missions that involved no peace at all.

From the book After The War: Surviving PTSD and Changing Mental Health Culture by Stéphane Grenier with Adam Montgomery, copyright © 2018. Reprinted by permission of University of Regina Press.