moo Kyah and Eh Blu Htoo’s apartment in Hamilton, Ontario, is small and plainly furnished. The walls are decorated with glossy magazine pictures of Karen and Thai pop stars; leftover Christmas tinsel glitters around a shrine of happy, airbrushed faces. Just after my arrival, one Saturday afternoon in February, a handful of young men shuffle in the door, hoping to set up their electric guitars—the sitting room is angular with amplifiers of all sizes—but upon seeing me, a stranger, they grin, blink at the floor, and scuttle away again. I call out, “You don’t have to leave!” as the door clicks shut behind them.

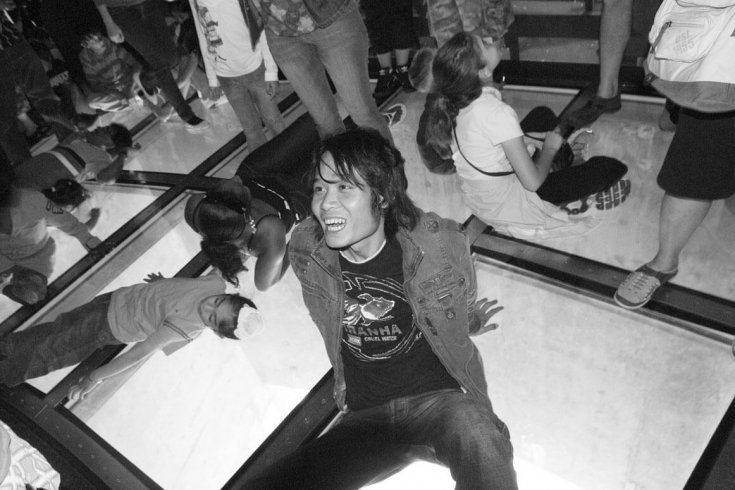

My friend and translator, Ler Wah Lo Bo, laughs and says, “The young men are shy. But they are also curious. They’ll come back.” With his rugged good looks and his perfectly in-tune baritone, he’s famous in the Karen community for his fine renditions of Johnny Cash and other country and western singers. Professionally, he works as a phone interpreter for Karen people across North America, but he has also spent a great deal of time and energy supporting recently arrived Karen refugees in Toronto, Hamilton, and the surrounding areas.

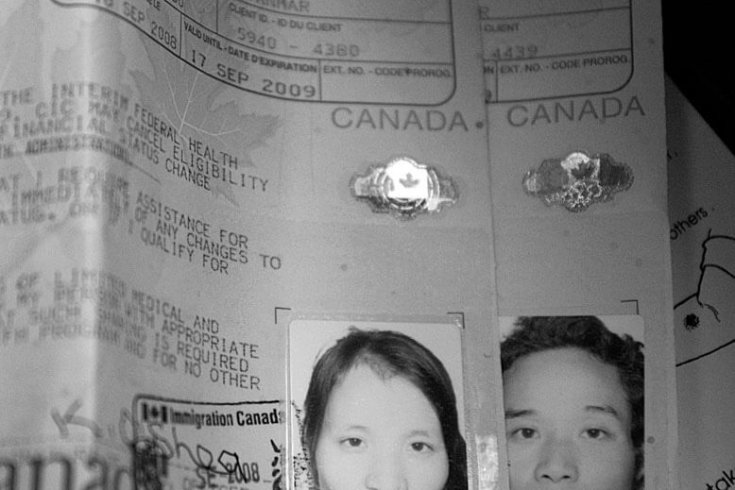

New arrivals need help finding and settling into strange new apartment buildings, using the transit system, and filling out health care and legal paperwork. They have all come here through a Canadian government resettlement program that since 2006 has seen over 3,000 Burmese Karen refugees begin new lives in cities and towns across Canada. By the time the program ends later this year, another 900 men, women, and children from refugee camps on the Thai border will be experiencing for the first time the strangeness of snow and political freedom.

Petite, twenty-three-year-old Moo Kyah is more willing to talk than her husband; she’s better at English. “We learn it every day at school. All day. But is very difficult. On Sunday, I go sometimes to the English Baptist church.” I’m surprised there isn’t a Karen church, considering there are now some 200 refugees, many of them devout Baptists, living in Hamilton. She quickly clarifies: “Oh yes, we have our own church, too, in our Karen language. Sometimes I go there in the morning, then I go to the other Baptist church in the afternoon. To listen to the English. You know, for practice.”

Eh Blu Htoo turns his broad, handsome face in my direction, shakes his mop of hair, and speaks a long paragraph in Karen. Ler Wah Lo Bo’s translation is a tidy summary: “He says English makes him suffer, a lot. But he wants you to meet his six-year-old sister. She speaks it perfectly, no accent!” Eh Blu Htoo’s parents and his seven siblings came to Canada in 2006, three years before he and Moo Kyah did. He missed registering for the Canadian program at the same time as his family because, following many other destitute and semi-imprisoned refugees, he had snuck out of a camp to work illegally. After labouring on a Thai farm in slavery-like conditions, he was lucky to return to the camp in time to make the program’s final deadline. And here he is, grinning at me and rubbing his English-addled head. The challenge of learning the language is particularly ironic, since a fierce struggle for the right to speak and to be Karen has led him, his wife, and a handful of his people to Canada.

In their own country, Burma, it is not exactly a crime to belong to one of the country’s many ethnic groups, but it tends to make life more dangerous. In the 1930s and ’40s, the Karen people fought beside British colonialists against the Burmese independence fighters, a nationalist force mostly made up of Burmans, the country’s major ethnic group. In return for the Karen people’s loyalty, the British reportedly promised to help them form an autonomous state of their own. With the crumbling of the Empire, that grand promise never came to fruition. Britain essentially washed its hands of the Karen once the brilliant young Burmese freedom fighter General Aung San negotiated the country’s independence in 1947.

General Aung San recognized that stability in the fledgling democracy depended on building a solid peace with its ethnic populations, but he never had time to develop his vision. Shortly after coming to power, he and most of his cabinet members were assassinated, plunging the country’s future into uncertainty. In 1962, another military man, Ne Win, staged a coup d’état and became Burma’s ipso facto dictator for the next twenty-six years. In 1988, he handed over power to a bevy of generals now known as the spdc: the State Peace and Development Council.

Over the past half century, the Karen, the Karenni, the Shan, the Mon, the Chin, the Kachin, the Wa, the Naga, the Rakhine, the Kayah, the Palaung, and other ethnic groups have fought a bitter guerilla war against the dictatorship’s well-armed battalions. Some historians consider it the longest-running civil conflict in the world. Western governments and human rights organizations regularly protest the house arrest of Nobel Peace Prize winner (and daughter of General Aung San) Aung San Suu Kyi, and make demands for the release of over 2,000 political prisoners who are suffering in prisons across the country. In an unprecedented move, the UN has recently called for Burma’s military leaders to be investigated for allegations of war crimes. Some of the most egregious abuses—slave labour unto death, summary execution, the amputation of penises and breasts, the rape of women from the very young to the very old—take place far from the heart of the country, against people who speak languages the Burmese soldiers cannot understand.

The last time ivory-skinned Moo Kyah was in Burma, she was six years old. A Burmese army battalion attacked her village one day when her mother wasn’t home. Amid mortar explosions, gunfire, and screaming women and children, her big brother ran with Moo Kyah clinging to his back; another brother and sister were old enough to run beside him. They fled into the jungle and found others who had escaped. Eventually, they were reunited with their mother. After two weeks of hiding and another Burmese army attack, they decided to walk to Thailand, into the precarious safety of a refugee camp.

There are ten camps along the 1,600-kilometre Thai border, with a total population of about 140,000, from over a dozen ethnic groups, the majority being Karen and Karenni; each is a place of painful contradictions. As one walks along the narrow, dusty paths lined with thatch huts, the camp resembles a sprawling village, more stuffed with people than one usually encounters in rural Southeast Asia, with smaller, simpler buildings and fewer shops—and less food, and not enough open space for the children or the gardens or the animals—but still vaguely homey. Men and women sit on the porches of the little huts, idle, or with small tasks occupying their hands. Frustrated energy wafts through the entire area like smoke from the innumerable charcoal cooking fires. Peoples’ faces, hands, and bodies are marked, sometimes literally scarred, with the fraught history of their nation. But the rampant domestic abuse and sexual assault that result from a traumatized population living in overcrowded, impoverished conditions remain largely invisible to visitors.

Though the camps offer some security from overt attacks by the Burmese army, they are essentially insecure places. After all, to be a refugee means you do not have a real home, that you cannot come and go as you please (the areas are fenced and guarded by Thai soldiers), that you live in a foreign country whose citizens despise your presence, that you have few prospects (if any) for the future. Yet thousands of children are born here every year. Their eyes glitter from the low doorways, from behind clumps of weeds and stunted banana trees, through chinks in thatch-woven walls. They are like children everywhere, often dazzlingly beautiful, possessed of lively intelligence and humour, hungry to eat up the world.

All of Eh Blu Htoo’s younger siblings were born in the narrow confines of the refugee camp where he himself grew up, and where he met and married Moo Kyah. Her mother and siblings are still there, and may never get out. When the Canadian resettlement program for Burmese refugees ends later this year, it will not be renewed. There is no shortage of destitute populations to help: over ten million people in the world today are refugees. Every year, twenty-some countries accept roughly 100,000 of that number to become new citizens. Canada is one of the most accommodating, settling from 10,000 to 12,000 refugees annually. Canadian citizens and community groups can sponsor Burmese refugees privately, but it is a complicated, time-consuming, and expensive process. When someone departs the precarious world of the border and begins a safe life in a new country, some kind of miracle has taken place.

Ironically, the magnifying glass of immigration law in Canada sometimes burns a hole right through the miracle. While Eh Blu Htoo and Moo Kyah already have their permanent residency status and will become Canadian citizens within two years, translator Ler Wah Lo Bo remains trapped in a bureaucratic nightmare. He has lived here as a legal refugee for eight years, working and paying taxes, but the Canadian government has yet to grant him permanent residency, citing section 34(1)(b) of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, which states that a foreign national is inadmissible for residency in Canada on security grounds if he has engaged in the subversion by force of any government.

When he decided to apply to Canada as a refugee, he was surviving on the Thai border by working for ngos. He helped organize the International Campaign to Ban Landmines; he documented abuses against the Karen people for a human rights organization; he acted as a translator. But years before that, he was a soldier for the Karen army, fighting against the Burmese dictatorship—information he voluntarily disclosed to Canadian officials. When they accepted him as a refugee, he assumed that he was on the road to becoming a Canadian citizen and that it was only a matter of a couple of years before he could bring his wife and children over from the refugee camp in Thailand.

But in the aftermath of 9/11, American and Canadian governments became particularly wary of any refugee claimant who has also been an armed combatant, though the Karen army—the Karen National Liberation Army—is not classified as a terrorist organization. (Not to mention that a handful of former Burmese resistance fighters have been allowed to join the Canadian Armed Forces.)

Ler Wah Lo Bo now waits for the Canadian government to decide what to do with him. If he is deported back to Thailand, he returns to the old limbo, lonelier this time because his wife and children, tired of waiting to join him, immigrated to the US through another relative. His wife died there two years ago in a car accident. If he is sent back to Burma—because the Thai government will not accept him—he will be executed.

“You see? ” he says, lifting his eyebrows and motioning his head toward the door. “I told you they would all come back.” I smile but don’t say a word until the guitar players take off their shoes and come into the little sitting room.

Ler Wah Lo Bo was right; they are a curious bunch. For the next hour, we sit around the kitchen table and eat noodles, drink Canada Dry ginger ale, and talk about the trials and pleasures of living in a cold, free country where so many people drink coffee all day long. I show them pictures of my family, and of Rangoon, Burma’s biggest city. None of them have ever been there. We talk about how much they miss the friends they left behind, and how they sometimes miss their old lives, which were hard but simpler, more comprehensible.

“Did you ever feel guilty for not joining the armed struggle against the Burmese government? ” I ask. Ler Wah Lo Bo translates to make sure everyone has understood. His words, in Karen, seem to give them permission to speak, and they do, among themselves, not looking at me. Meanwhile, I consider the guitars leaning against the walls of the room. In the Karen army camps in the jungle, these black instruments would be guns—old, much-repaired semi-automatic and automatic rifles.

A few minutes later, he reports back. His voice is soft: “We all believe in the revolution, that it is right. We must fight against the regime and help the Karen people. But there are different ways to fight. There are other ways to help our people.” That is why he applied for, and received, an honorary discharge from the army he gave years of his youth to. He opens his hands toward Eh Blu Htoo and his friends. “They all have uncles or cousins or friends in the Karen army. They have all gone to the funerals of those who died as soldiers. And the camps are full of amputees, because there are so many land mines in the jungle. They say it’s hard to join the armed struggle when you see the amputees every day. They were afraid to die.”

I look around at the faces in the room. I’m glad they’re here, in this small apartment in Hamilton. “I’ve asked you all so many questions. Now, is there anything you’d like to ask me? ”

There is silence at the table. Then Moo Kyah, who is at the counter cutting up a chicken, turns around and dries her hands on a cloth. She has been listening carefully to everything, understanding everything. “I have just one question. Is the Canadian government going to allow more Karen refugees to come to Canada? ”

This appeared in the June 2010 issue.