The Ninja of Love was a scientist. Take a complex system, learn it, identify a problem, formulate a hypothesis, conduct an experiment… if one predicted outcome fails to materialize, try another.

In the six-sided cage at Ed’s Rec Room in West Edmonton Mall—where the Ninja now stood, squared off against an equally pallid and shredded fighter—the system was indeed complex: two men, skimped out in shorts and thin, open-fingered gloves, surrounded by a mesh enclosure two metres high and seven metres across, ready to battle for three five-minute rounds unless someone gave up or got knocked out first.

There were many permutations to consider. He could knock out his opponent with a punch or kick or elbow or knee, or gain a submission via chokehold or joint lock or barrage of blows—standing or in the clinch or on the ground. And he had to defend against the same, without recourse to bites or headbutts or groin strikes or other forms of foul play. Every option seemed to present itself at once.

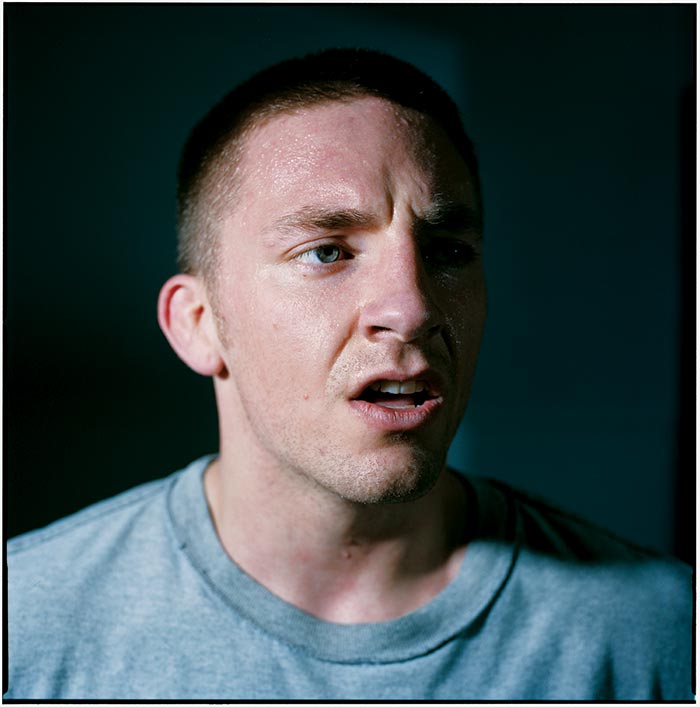

The Ninja—a.k.a. Nick Denis, a twenty-four-year-old biochemistry master’s student at the University of Ottawa—had tried to control for all variables. He’d scouted his opponent, a 145-pound fighter from Vancouver named Dave Scholten, by tapping into the sport’s obsessive online rumour mill. Then he’d hit the gym twice a day, five days a week, with an extra session on Saturday. He’d alternated cardio with jiu-jitsu and Muay Thai kick-boxing, sparring constantly with his Ronin Mixed Martial Arts teammates—three five-minute rounds of Muay Thai, then three five-minute rounds of boxing and wrestling, then three five-minute rounds of mixed martial arts. His coaches monitored everything, offering advice ranging from the precise (“Jab, cross, move, jab, cross, move”) to the sadistic (“Don’t throw anything that’s not meant to hurt the guy”). Even his diet was calibrated: whole grains, lean meats, protein shakes, a plantation’s worth of fruit.

When finally his bout had been announced, Denis emerged to a crowd of 1,500, their roars drowning out the crash of bowling pins and the dings of video games from the adjacent arcade. He’d wanted to ride in on a Segway, but was prevented by the stairs leading to the cage. The Ninja of Love was a scientist, sure, but he had a taste for the absurd. He’d dubbed his fighting style “snuggle-jitsu” and fought in tight spandex “mandies” instead of the usual long board shorts because, he said, “they’re sexy and give me special powers.”

Denis had taken part in fight cards outside his province before, forced across the Ottawa River to Gatineau, Quebec, by the sport’s illegal status in Ontario. But this was something new: a Western crowd, a Western opponent. A title fight for an $800 purse and, potentially, the attentions of Ultimate Fighting Championship (ufc), the sport’s biggest showcase.

Denis’s guiding theory through the first two rounds was that Scholten would try to go to ground and get a submission. So he stood in wait, striking and retreating when Scholten lunged in to wrench him down and, if that failed, deploying the ground guard he’d perfected in training.

Everything changed at the start of the third. With Scholten holding an edge, the exhausted fighters converged to touch left gloves, a sign of mutual respect. Suddenly, Scholten flared a disrespectful right hook over his extended olive branch. Boos rang out, and Denis stumbled backward, shocked. A dark look crossed his face.

He recovered quickly, dragging a charging Scholten to the ground. “Hit him for being cheap!” a woman yelled. Scholten gained a reversal, then both men scoured for thirty seconds for a free limb to contort or a patch of skin to punch, until at last Denis countered, stood, and gestured theatrically for his opponent to stand. The crowd bellowed its approval.

When Scholten rose, Denis stepped in with a left hook, then a knee to the head, then an uppercut to the jaw. Scholten’s legs gave out, and he made a desperate lunge for Denis’s feet. As an official with Edmonton’s fight commission looked on from a few metres away, Denis strolled away disdainfully. Scholten attempted to rise, but Denis fired a hard, spinning kick that brushed Scholten’s hair, leaving the Vancouver fighter looking deranged and scared. He gamely tossed a few wild punches, but Denis deflected them, grasping Scholten’s neck and scuttling him with two knees to the face. Scholten, crumpled on the canvas, accepted three right hands without complaint, compelling the referee to end the fight.

The scientist stalked to the centre of the cage, dropped to his knees, and thrust his fists to the air in triumph. Before him sat Scholten, punch drunk and propped up against the chain-link wall, red spilling from forehead to torso to yellow cage floor.

Caged ignorance. Human cockfighting. Ghetto-fabulous hooliganism. The list of epithets cast at mixed martial arts by those who find it animalistic and incomprehensible is a long and colourful one. Admittedly, if boxing’s formula of intricate variations on simple rules elevates it to the level of Sweet Science, mma can seem more like Interdisciplinary Imbroglio: an ungainly mess punctuated by moments of brutal clarity, whose organizing principles only its professors appear to understand. And yet it has become axiomatic in fight circles that boxing is on the wane and mixed martial arts is on the rise.

It may say everything skeptics care to know that the seminal moment in mma’s ascent wasn’t a fight on the order of a Tunney-Dempsey or a Liston-Clay, but rather the launch of a reality TV show. The Ultimate Fighter made its debut on Spike TV in January 2005, following an episode of Raw, the flagship program of Vince McMahon’s World Wrestling Entertainment (wwe) juggernaut. The conceit was a spin on that of Big Brother: a houseful of aspirants stave off abuse and elimination en route to a six-figure contract with ufc.

Six seasons on, the show is averaging a respectable 1.1 percent share of viewers in its time slot, skewed heavily to the prized eighteen- to thirty-four-year-old-male demographic. “I call it the wwe–Vince McMahon theory,” says “Showdown” Joe Ferraro, host of a Toronto sports radio talk show dedicated to mma. “Every commercial, coming out of a break, you see an ad for a ufc pay-per-view. Then when you watch the pay-per-view, you see an ad for the reality show. It’s a mass-marketing machine.”

Pay-per-view revenue for ufc’s ten events in 2006 was $220 million (US), surpassing the takes of both boxing and wwe. Attendance is typically in the 15,000 to 20,000 range, and ufc is set to add Canada to its growing list of successful markets on April 19, when two-time welterweight champion Georges St. Pierre of Saint-Isidore, Quebec, headlines ufc 83 at the Bell Centre in Montreal. The event, which will take place before ufc’s largest-ever crowd, sold out in record time.

To many in this generation of TV-inspired fighters, though—and to the more informed of their fans—the rise of their syncretic sport represents not a triumph of marketing, but the fulfillment of a martial arts tradition that goes as far back as 648 BC, to pankration, a homoerotic mishmash of wrestling and boxing first staged at the xxxiii Olympiad. Pankration pitted nude, unarmed combatants against each other in no-holds-barred matches that lasted until someone submitted or was knocked out, severely injured, or killed.

Although we tend to think of fighting styles as originating in particular countries—boxing from England, karate from Japan, kick-boxing from Thailand, and so forth—in fact most began as hybrids. Karate, for instance, was systematized in Okinawa after its upper classes fused influences from elsewhere in East Asia with their own style, ti, in the late nineteenth century.

It was around the same time, on the heels of the age of imperialism, that martial arts began to cross-pollinate via the high seas. One of the first (and unlikeliest) amalgams was Bartitsu, the eponymous brainchild of Edward Barton-Wright, a British engineer who had worked in Japan. Barton-Wright devised his style as a way for London’s cheekier gentlemen to settle disputes with ruffians without having to remove their top hats. With roots in jiu-jitsu, stick fighting, and boxing, Bartitsu was popular enough for a time to turn up in the Sherlock Holmes short story “The Adventure of the Empty House,” in which Holmes vanquishes Moriarty using what Sir Arthur Conan Doyle erroneously describes as “baritsu.”

A more lasting example is judo. Rooted in Japanese jiu-jitsu (itself a seventeenth-century coinage covering a range of grappling styles), the style incorporated ideas from everywhere, including Western wrestling. It also became the basis for the first twentieth-century attempt to create a truly interdisciplinary combat system, sambo, which blended folk-wrestling styles from across the Soviet empire before being codified by the Red Army in 1938.

The direct progenitor of North American mma, however, is vale tudo (anything goes) competition, which began in Brazil in the 1920s. For decades, vale tudo was dominated by Rio de Janeiro’s Gracie family, which created and refined a style called Brazilian jiu-jitsu (bjj), a blend of Japanese jiu-jitsu and judo that emphasized joint locks and chokeholds. The Gracies brought their sport to North America in 1993, staging the first Ultimate Fighting Championship, a round-robin tournament without weight classes or time limits, in an eight-sided cage at an arena in Denver.

ufc 1 was promoted not as a showcase of a merged style, but rather as a way to settle the debate over which martial art was best—a meme that had gained traction among young North American males thanks to Bloodsport, the 1988 genre flick that brought Jean Claude van Damme to fame, and to the releases of the wildly popular arcade games Street Fighter II and Mortal Kombat, in 1991 and 1992, respectively. ufc’s first champion was Royce Gracie, who easily defeated bigger opponents with his bjj submissions. bjj soon became the base style of choice for most fighters, with other disciplines layered in to create the amorphous mixed martial art seen today.

As the 1990s progressed, ultimate fighting developed both a cult following and a seamy reputation, the latter owing in no small part to Arizona senator John McCain’s high-profile campaign to ban the sport in all fifty US states. The disrepute began to change in 2001, when the Unified Rules of Mixed Martial Arts were established in New Jersey, the first of many jurisdictions to adopt them. Among other strictures, the Unified Rules prohibited thirty-one especially violent actions, including headbutting, eye gouging, and striking the groin, spine, or back of the head. This made the sport friendlier to advertisers and, crucially, to legislators.

Quebec was the first Canadian province to stage mma events. Initially, the athletic commission there was loath to endorse the sport, so starting in the mid-1990s First Nations reserves acted as hosts, at first illegally and then under an agreement with the provincial regulatory body. These events—and the financial windfalls they were reaping—paved the way for Quebec to start officially sanctioning fights in 1998. Municipalities in British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia later followed.

In Canada’s largest and stodgiest province, meanwhile, mma remains illegal despite an abundance of top-notch pugilists such as Nick Denis. Debate has been rancorous, with advocates charging that Ken Hayashi, head of the Ontario Athletic Commission, is gumming up the legalization process because he’s biased against the sport’s violence. With Hayashi adamant that sanction is not forthcoming, a group of Ontario promoters decided late last year to follow the Quebec model of legalization, setting up the province’s first-ever “legal” mma event on the Six Nations reserve near Hamilton.

It’s a crisp Halloween morning in southwestern Ontario, three days away from the Rumble on the Rez. A few doors down from Crystal Wedding Chapel and Drive-Thru, in a strip mall in the heart of London, the Punishment Pound has been operating at near-capacity since 8:30 a.m. Chester Post, one of three members of the Pound, finished his shift on the loading dock at a heating and cooling supply company at 4 a.m., and now he is here, launching lumbering high-impact kicks at a heavy bag while Gaston Jarry, his teammate, wrestling coach, and boss on the dock, hugs it in place. The room, shared with a karate club, is littered with mats and pads. Long wooden bo staffs hang on a white wall embellished with painted belts and martial arts platitudes.

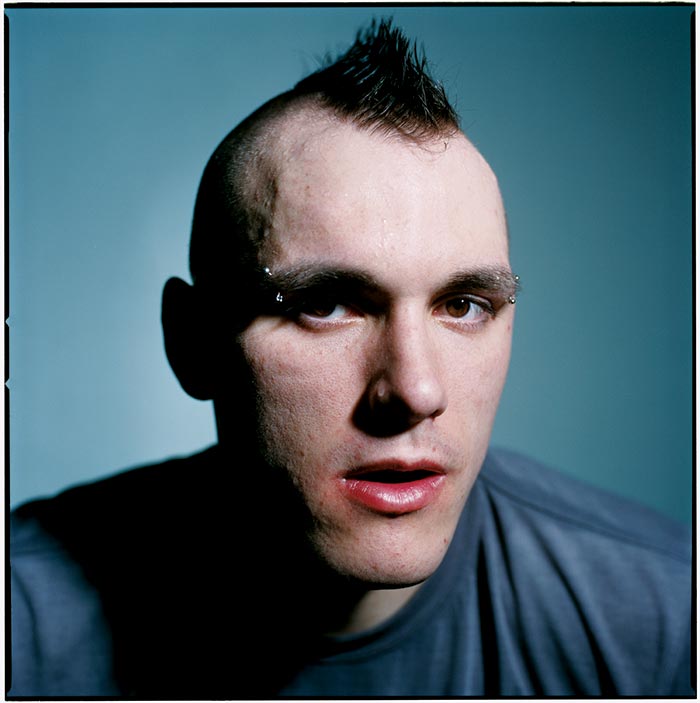

Like Denis, Post is twenty-four. His parents brought him to Canada from the Netherlands when he was one, moving the family from town to town as they operated small businesses and farms to make ends meet. An imposing six-three, 210 pounds, he sports a shaved head and two silver barbells that radiate from his eyebrows like antennae.

Post’s mma career to date has been a Forrest Gumpesque series of unlikely encounters, from the way he got into the sport (by hunting down Gary Goodridge after seeing a tape of him fighting in one of the earliest ufcs and convincing the Barrie-based brawler to train him) to inflicting a concussion and a broken eye socket on a former wwe wrestler, to his knockout win over a 525-pound sumo wrestler who had to be weighed in on a truck scale. Next up: headlining Ontario’s first stab at an official mma card.

Clad in bright blue and yellow shorts with a stitched-on cobra poised front and centre, Post halts his training session and begins acting as a takedown dummy and coach for Shaun Hogan, the newly arrived third member of the Pound. When they finish, Post sits down at the edge of the mat, revealing an easy smile and a soft-spokenness that belie the latent aggression he says led him to the sport. More than someone who enjoys hurting people, he sounds like someone who has often been hurt. He talks about betrayals by promoters, about wanting to shelter his teammates from the harsher side of the business. About needing to take a punch before he can focus during a bout. He keeps fighting, he says, because he is “a pain addict.”

Despite the high-profile victories, Post’s record is an unimpressive-sounding seven wins, nine losses, and one draw. “If you can’t take a loss, you don’t belong in the sport,” he says with a grin, his words thickened by a pierced tongue. With so many ways to lose a bout, it’s true that every mma fighter must get used to defeat. Post’s losses, though, have all been by technical knockout, and the last two were particularly brutal.

At the Rumble, set for the Iroquois Lacrosse Arena in Hagersville, he’s matched up against Chuck Monture. Organizers have revealed only that Monture is five-ten, this is his first fight, and he’s the son of the event commissioner. But Post recently received grapevine notice that his opponent is in fact an experienced member of a Brazilian jiu-jitsu club in Niagara Falls. The omission, coupled with the nepotism and Post’s losing record, suggests that he’s being set up for defeat.

The demands of training for a high-profile fight are more than Post can afford right now, and his regimen has been spotty compared with the one Denis followed. Though he still drives down every Saturday to work with Goodridge in Barrie, Post has otherwise resigned himself to a little ground fighting, a little takedown defence, and a little heavy bag, with not much in the way of cardio. Although he would prefer to fight as a 185-pound middleweight, this time out he will be a 205-pound light heavyweight. His 205, he acknowledges sheepishly, is “a little flabby.”

The Punishment Pound’s comparatively haphazard approach is especially worrisome because Post will have to keep Monture away from a partially detached retina suffered in his last fight. The doctor told him he should take a year off before fighting again, that one solid strike could lose him his sight. But the chance to fight before an Ontario crowd—including his mother, Irmgard, who will see him in action for the first time—is too good to pass up. Mustering what would be unconvincing bravado had he not once fought with a broken arm, Post says that if the lights go out, they’ll go out his way—“guns blazing.”

Fight night on the Six Nations reserve is a pale reflection of a Vegas main event. The fans dotting the neon orange seats are overshadowed, and at times seemingly outnumbered, by gigantic glossy banners displaying Iroquois lacrosse players. Tickets for the event are pricey, especially for a first-time affair taking place hours outside Toronto: $50 for the stands and $75 for the floor, with tables around the traditional elevated boxing ring where the fights will take place going for $1,200 each. The concession stand is churning out popcorn and hot dogs at a steady pace, however, and local businesses such as Sit ’n’ Bull Construction and the Lone Wolf Pit Stop have rallied around the event. The event’s organizers have also flown in burly and genial ufc veteran Dan “The Beast” Severn to glad-hand patrons in one of the washed-out hallways skirting the arena seats.

Such is the hardscrabble lot of many North American promotions, a patchwork assembly of roughly three tiers. At the lowest level are fly-by-night and start-up operations such as the Rumble. Then there are the established minor leagues, which include the US Army–sponsored International Fighting Championships, Canadian online gambling magnate Calvin Ayre’s Bodog Fight, and King of the Cage, whose Western Canadian offshoot is run by a professional gunslinger out of the Wild West Shooting Centre at West Edmonton Mall. Above them all sits ufc.

The Rumble’s promoters have kept tonight’s lineup a secret, for fear the Ontario Athletic Commission (oac) will punish combatants for participating in a renegade event. Despite the absence of the oac, safety and medical protocols have been a priority, which is not always the case with lower-tier events. Each fighter has submitted the results of a recent blood test, and a doctor is on hand for pre-fight checkups. He’ll be at ringside for the bouts, backed by a half-dozen medics.

Prior to the event, the promoter, Jack Bateman, a thin and intense twenty-nine-year-old from Newmarket, Ontario, hustles about the arena in a dark suit. Pausing for a moment in one of the dressing rooms, Bateman, an electrician by trade, explains the decision not to release names. “We didn’t know 100 percent whether we’d missed anything legally,” he says. “Better safe than sorry.” He is, he adds, working with backers from Calgary and Montreal to lobby the oac.

Out on the floor, in the first row of seats behind a neutral corner, sits Irmgard Post. Sporting a shock of dyed burgundy hair, two dazzling green triangles that sway beneath three sets of studs in each ear, and a pierced tongue in common with her son, the vivacious Mrs. Post confides that she has already made her presence known to the referee, a granite-based life form known as Kaz. She wagged a finger at the official, an experienced fighter whose real name is Wojtek Kaszowski, admonishing him to keep the combatants away from the edge of the mat, where they might become entangled in the ropes or fall to the floor.

Rumours about Chuck Monture are floating around the arena. He’s had fifty fights down in the States. He’s a former hockey and lacrosse player. He likes to go to the ground. He likes to stand and trade. In response to the hearsay, Post has decided on a late strategy change: he’s going to bring a little Rumble in the Jungle to the Rumble on the Rez, accepting whatever punishment Monture doles out early, then taking advantage of his fatigue late, à la Ali in Zaire. He already took his first blow a few days ago, he says: an air conditioning unit fell on him at work, leaving a gash on his right shin.

The event opens with a greeting, delivered in the Cayuga language by a local elder to the spectators half-filling the 2,400-seat arena. Then the opening pulses of Gnarls Barkley’s “Crazy” kick in, and, as a tinny-sounding Cee-Lo Green screeches out, “I remember when/I remember/I remember when I lost my mind,” the Toronto bjj club bounces into the arena in a conga line, hands gripping each other’s shoulders. Second in line is their man, the well-inked middleweight John “Irish” Sheil, who distinguished himself in the dressing room with his bright brogue and blithe manner. He pauses at ringside so that abrasion-preventing petroleum jelly can be spread over his forehead and cheeks, then climbs the stairs. His opponent, Trevor Ziegler, soon follows.

With the evening’s first fight comes the first helping of blood, courtesy of an early knee to the Irishman’s head. For a time, the two fighters stand and brawl, powdering each other’s skulls with their four-ounce gloves. Then Irish turns to his bjj training, taking Ziegler to the ground and bypassing a leg lock before flipping his opponent onto his stomach. Rather than going for a bjj-style choke, however, he straddles his opponent between his knees and initiates mma’s most startling ritual: the ground and pound. With Ziegler quaking toward defencelessness, Irish taps out head strikes like a furious, legless Fred Astaire. The first sanctioned mma match in Ontario ends seconds later, by the grace of Kaz. Victory, technical knockout, Irish.

“In the most violent fights,” Joyce Carol Oates wrote of boxing, “the predominant image is that of the referee hovering at the periphery of the action, stepping in to embrace a weakened or defenceless man in a gesture of paternal solicitude.” As society became less inclined to sanction the brutality of the ring, she noted, the referee’s role as protector, as enforcer of civilization, became commensurately more important.

In this respect, mixed martial arts, with its magazine-thin gloves and many-things-go ethos, has picked up where boxing left off. The sport’s emphasis on fast and varied submissions, though it is in many ways more benign than the repeated doses of dynamite that fuel boxing’s lust to have someone “knocked out of Time” (as Oates put it), nonetheless demands a more attentive official. Poorly checked, the rapid-onset dominance prized by mixed martial artists would quickly cause broken bones or death—a lesson driven home by the sport’s second known in-ring fatality this past December, following a drubbing in Texas. Much in mma lies in the hands of the referee.

Kaz’s meaty paws are certainly full as the pageant at the Iroquois Lacrosse Arena swirls along. Each fight seems to end differently. Bout number two concludes after only forty seconds, with one combatant locking in an arm bar moments after being slammed from shoulder height onto his head and neck. In number three, two welterweights wind down to a decision. As is often the case with mma, the crowd falls silent during their extended ground sessions, even booing the “lay and pray” displays.

The best battle of the night is the fourth, a buffet of low leg kicks, takedowns, and narrow escapes that comes to a sudden end in the second round after Igor Caetano, a smooth-chested pit bull whose cornerman, “Uncle,” spent the match bathing the arena in Portuguese, drifts to the canvas in exhaustion. Kaz is forced to intervene when Caetano’s crimson-splashed opponent launches a flurry at the dormant fighter.

The wonderfully named Todd Kick, a local behemoth, then woefully fires off none in a tko loss to half-man, half-tattoo Jason “The Monster” Bissonnette. Rob “Spider” Dicenso follows with the night’s most impressive performance, seizing victory (and possibly a nickname) from “The Silent Assassin,” Paul Ebejer, in an arm-triangle choke at the twenty-three-second mark.

Throughout, the trappings of boxing and ufc are mimicked. Sponsors and future events are plugged. Round cards are sashayed around by the “Ménage” girls. Stilted thank yous are offered by winners to the audience. Celebrities are present, in the form of glam rocker Robin Black. Those in attendance all seem to be under thirty, male, and black clad, their gear emblazoned with slogans such as Violence Solves Everything and First I Ground You, Then I Pound You.

The penultimate match of the evening, right before Chester Post’s headline bout, is a shock-value special. After a back-and-forth opening exchange that includes a spectacular slam, Matthew McDonald—who, alone among the night’s combatants, crossed himself in Christian prayer before the opening bell—charges out just after the three-minute mark, windmilling a right hand to the upper incisors of his off-balance opponent, Bill Frazier. Frazier’s lip bursts, blood and consciousness escaping as he plummets to canvas. He is out on arrival.

McDonald instinctively follows to the mat for the pound, but Kaz surges to the rescue, shoving him away after only a glancing blow. As cornermen and medical personnel pour in, the victor rushes across the ring, united with the crowd in frenzy. He turns toward his downed opponent, cocks his gloved right hand like a gun, and pantomimes Frazier’s murder. Twenty paces away, Irmgard Post looks to the sky. “Ohh Jesus!” she says.

Her son hasn’t seen what just transpired. Prior to his dressing-room prep, Chester was wandering the arena, watching some of the action, talking with other fighters, trying to calm his nerves. An aboriginal reserve should be home court for him—he lived on one for seven years—but because he’s fighting a local he expects to play the villain tonight. The role doesn’t suit. After entering to the hard rock of Godsmack’s “I Stand Alone,” he twice encourages the fans to applaud Monture’s banner-waving procession.

Spurred on by a vocal Goodridge, who is seated next to Irmgard, Chester comes out after the bell spitting kicks at his opponent’s legs, each eliciting a wince. The bald, rotund Monture soon brings the fight to the ground with a leg sweep. With her son’s opponent now in control, Irmgard casts her gaze to the arena floor. Standing and turning her back to the ring, she fusses with camera equipment, wilfully ignoring the action behind her. By the time the round ends, with Chester regaining the upper hand, she is at the concession stand buying coffee. She witnesses the finish at a remove, sipping from a polystyrene cup and darting glances at a ringside screen.

After a brief exchange of punches to begin the second, Monture attempts a throw, but Post trips him and gets into prime ground-and-pound position. With two long arms pumping away from above, the local grappler can do little but cover his head with his forearms. By the tenth blow, his mouthguard is on the mat. By the fifteenth, the fight is over. A convincing victory for Post, who rises to scattered cheers and the promise of $1,500.

He takes the microphone, thanks his opponent, and declares with a broad smile, “I’m tired of fighting away from home.” Echoing a catchphrase of former wwe star the Rock, he adds, “Finally mma has come to Ontario.” In his free hand, he holds the trophy given to all of the night’s winners, a furred and feathered peace pipe.

In the aftermath of the Rumble, Jack Bateman and oac commissioner Ken Hayashi took turns sniping at each other in the mixed martial arts media. “Those guys are taking a big chance with these shows,” Hayashi told mma Weekly. “If someone gets seriously hurt, there will be liability issues, and it will set the sport back several years in Ontario.” During the 1990s, fighters in Quebec were sometimes charged as they stepped off the reserve, and Hayashi noted that he had indeed asked police to investigate the Rumble. He was apparently directed to speak with band police, a fact that prompted a jab from Bateman: “They were sitting in the front row.”

Hayashi, a karate black belt and a martial arts veteran of some forty-five years, said the oac won’t sanction mma events because the sport hasn’t established a safety record at the amateur level, and especially because the relevant legislation doesn’t cover it. “Our lawyers have concluded that these events are clearly illegal under Section 83 of Canada’s Criminal Code,” he said. This justification is perplexing to many, however, since Section 83 bans prizefighting but excepts professional events sanctioned by provincial councils—which is why other provinces (and, in what seems like a sovereignty dare, on-reserve commissions) can endorse them. The argument appears to be a Catch-22: the oac refuses to sanction events like the Rumble because they’re illegal, and they’re illegal because the oac refuses to sanction them. Hayashi counters that promoters—and bodies that have made the decision to sanction—will see their interpretations of the law overturned in court if they’re ever sued.

An update to the code is on Parliament’s back burner, but in the meantime critics accuse Hayashi of feinting to avoid the hassles of legalization. “If I go to Ken and say, ‘Let’s develop this, make it as safe as possible, and sanction it,’” Joe Ferraro complains, “he doesn’t want to hear it.” Although the point about developing an amateur safety record remains, Ontario’s pro-mma partisans see the stonewalling as a hangover from the early years of ufc and a failure to see beyond the hype used to market the sport.

A second, better-attended Rumble on the Rez was held in Hagersville in early February (with Chester Post grounded and pounded into a tko loss), and plans are in the works to take the promotion to other reserves. But until something changes, such events will remain on questionable legal terrain in Ontario.

The sport’s violence and sensationalism threaten it elsewhere as well. Last September, for example, Vancouver’s city council voted to ban mixed martial arts events. And ufc, absent a broad, mma-educated fan base, appears to be losing some of its momentum. Boxing staged a resurgence in 2007, attracting record pay-per-view audiences for two Floyd Mayweather Jr. fights, thanks in part to the four-episode reality shows hbo aired in the run-up to the bouts. ufc’s pay-per-view buys, meanwhile, dipped, and its parent company’s credit rating took a hit from Standard & Poor’s. In response, ufc signed former wwe champion Brock Lesnar to headline its second card of 2008. The leviathan cried uncle after ninety seconds.

Nick Denis, for his part, would love for fans to appreciate the sport’s athletic aspects more than its “ultimate” trappings or messy finishes. Those who would interpret his fight in Edmonton as a consequence of blood lust aren’t getting the full picture, he stresses. He acknowledges that he was revved up by the crowd, but claims he never lost control following Dave Scholten’s cheap shot. Rather, he was almost disappointed by it. “I would expect a certain level of professionalism from him,” Denis says. “I wanted to punish him, as if what he did was wrong.”

This concern for professionalism places the Ninja of Love at odds with those who are more attracted to brawling than to the technical and mental discipline he sees as mma’s main draw. He recalls picking up the phone at the gym one day and hearing someone ask how to go about fighting in ufc. “I told him, ‘Train.’ He said he had no time. So I said, ‘In that case, just go to a bar and fight someone, retard.’”