Since November 2017, a network of Canadians who have lost friends and family to the opioid crisis has sent about 500 letters to Justin Trudeau. Affixed with photos of sons, daughters, brothers, and sisters, the letters remind readers that the victims of the crisis are not anonymous or forgotten—they are loved—and demand that Trudeau “do something” to stop the rising death toll. Led by Moms Stop the Harm, a national network of mothers whose children have been affected by the crisis, the campaign has yet to receive a response from the prime minister, and to date, it seems the federal government’s movement on the crisis has been inadequate. That hasn’t stopped the group and its allies from speaking out about the crisis. Here, several of these unlikely advocates share the stories of their lost loved ones, their lessons learned, and why they believe the crisis won’t be fixed until the stigma is broken.

❖ ❖ ❖

Sandi Tantardini

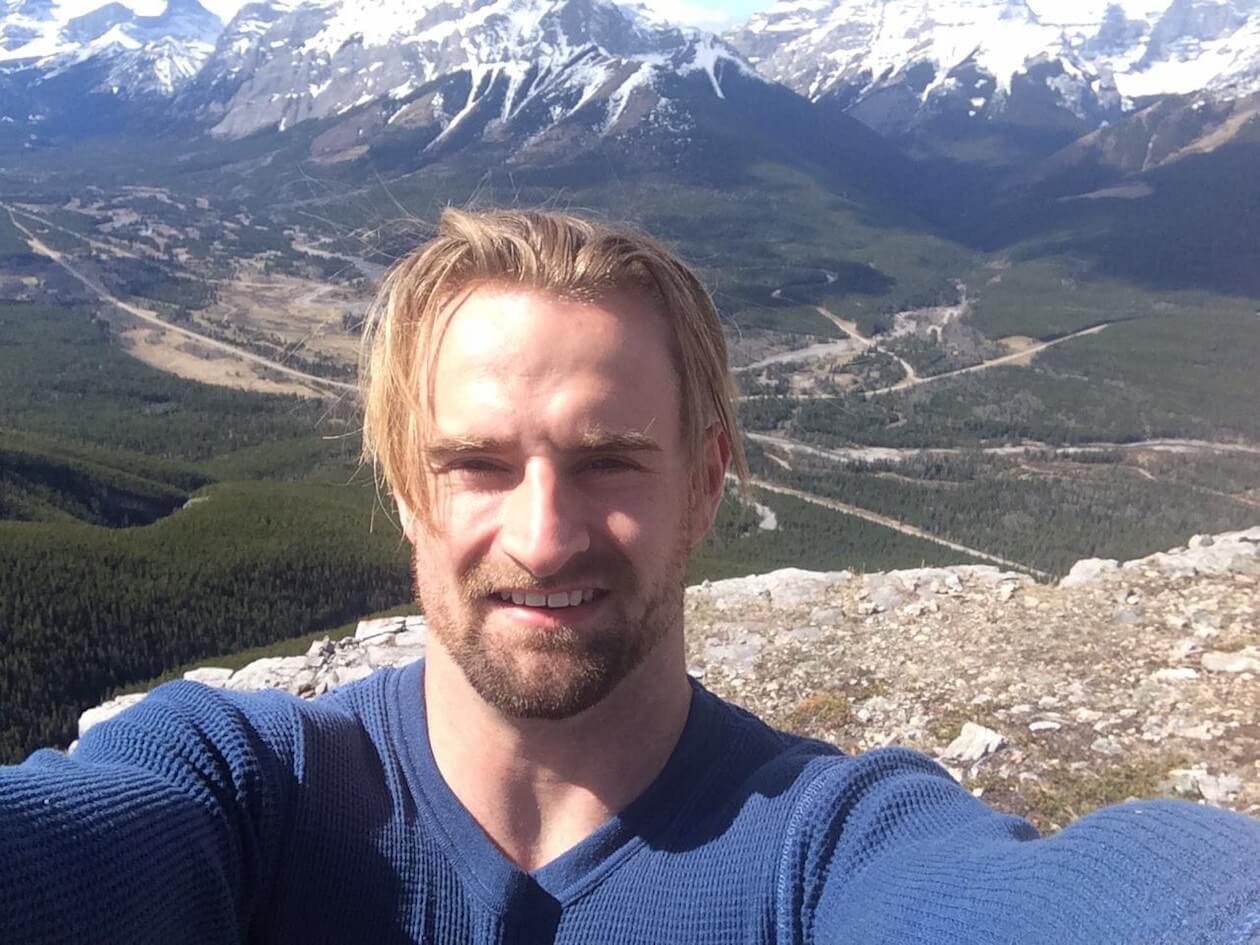

Growing up, my son Scott seemed to have it all figured out. My friends were calling him Mr. President when he was ten years old. He was charming, charismatic, worked hard in school, and carried this focused mindset into adulthood. Scott ran marathons, competed in CrossFit, had his own business, his own condo, and, when he first told me about his drug use, he was also engaged. But seven years ago, it just started to unravel. Scott’s drug of choice was fentanyl. He had mental-health challenges, like anxiety, and he’d already started to self-medicate with other drugs. He first tried opioids when he was younger, when he got his wisdom teeth taken out. He later told me that it was the first time he’d felt good, calm; he was eventually diagnosed with an anxiety disorder. I always say that when Scott found fentanyl, he found God. That’s what it was like for him.

I felt blindsided when Scott first told me. I’d worked in a veterinarian’s office, and we’d used fentanyl to help animals in pain. I associated it with medication. But that wasn’t the biggest mistake we made. Scott wanted to stop using drugs; he knew what it had cost him, and when he said he wanted to get better, he meant it with every fibre in his body. At the same time, we both had preconceived notions about methadone. We didn’t know there were other medically assisted treatment programs out there, like Suboxone. We didn’t know how difficult abstinence-based programs were or their low success rates. Knowing what I know now about the effects fentanyl has on the brain, I believe he didn’t stand a chance. I’ve since met many families whose loved ones struggle with drug use, and in talking to them, I know that most people relapse at some point.

Eventually, Scott moved out to Calgary, where he felt there were more treatment options for him. He was out there from the end of 2013 until the summer of 2016, when he died. Throughout that time, Scott had long periods of sobriety. At one point, he was twenty-one months sober. It helped a lot once he got into a concurrent-disorder program, one that treated his anxiety and his drug use at the same time. We would talk or text almost every day, and he would tell me that he was learning so much about himself and his anxiety. He was in that program for three months, and then he was released into transitional housing. Less than twenty-four hours later, he had overdosed. Then he was gone.

Scott never did any medically assisted drug-treatment programs. And I believe that’s what killed him. To me, abstinence based programs don’t work. This idea of willpower is such a huge misconception when it comes to drug use. I co-founded Niagara Area Moms Ending Stigma (NAMES) with Jennifer Johnston because advocacy is the only thing that kept me going after Scott’s death. I didn’t know what else to do. I didn’t want it to destroy my family. I didn’t want it to destroy me. Our group offers support to other families whose loved ones have died, but we also let people know how dangerous opioids are and why we need to start addressing the crisis. Nothing about drug use is black and white, but it’s pretty clear something needs to be done.

Leigh Chapman

My brother Brad died in August 2015. A security guard found him collapsed in front of a nail salon in downtown Toronto and called 911. He had cocaine, opioids, and amphetamines in his body, and he was alone. Brad had been homeless off and on for twenty years, and he had three children, siblings, a family who loved him. Still, when he was taken to the hospital, police listed him as “John Doe,” and for days, nobody reached out to us. None of us knew he was in the hospital on life support, languishing. When we finally found out, thanks to a curious spiritual counsellor at the hospital, we gathered, and my mother agreed to withdraw life support. Brad was forty-three. We were devastated.

After he died, I began to speak out about his life—and about the need for more services for people like him. I felt like I needed to do something to alleviate the paralysis I felt about being unable to prevent his death. And there were things that could be done to help. If Brad wasn’t using alone, he might not be dead right now. As a registered nurse, I helped advocate for both supervised-injection and overdose-prevention sites in the city. Eventually, in 2017, I was invited to a conference in Vancouver centring on harm reduction and what could be done to scale up sites in that city and elsewhere. I was excited to connect with other advocates there and to learn everything I could. I made sure to save a seat for one of my friends, Raffi Balian, a fierce harm-reduction advocate who worked in Toronto. But the seat stayed empty. Raffi overdosed before the conference.

I was inconsolable on the plane back to Toronto—just sobbing. Who goes to a meeting where their colleague dies? I became determined to make his death mean something. Overdose-prevention sites felt more urgent than ever. Then, in 2017, Toronto experienced a surge in opioid-related deaths. Rather than feel paralyzed again, I started a GoFundMe campaign to launch an overdose-prevention site in Toronto, setting the goal at $5,000. Shortly after, the mayor called a meeting, and during that meeting, two shelter workers had to leave because there were two overdose deaths at their site. I went home crying. A few of the others, however, went out for drinks, and that night, they decided enough. They’d already had a press conference scheduled the next day, and during it, they announced they were opening an overdose-prevention site—the next day. I got a call right after: “Leigh, we just announced our opening, can you go buy a tent?” I rushed to Canadian Tire. And the next day, we opened our pop-up site at Moss Park.

We quickly met our $5,000 fundraising goal, and when I later upped it to $50,000, we quickly met that too. Shortly after, we’d raised $75,000. As of August 2018, we were sitting at over $100,000. We have used that money to continue to fund the Moss Park site. In our first (almost) eleven months of operation, we moved from tents to a winterized trailer and had 9,062 injection visits and reversed 251 overdoses. In July, after receiving provincial funding, our site moved indoors to nearby location. We continue to fundraise for the Moss Park site and have recently opened another site in Toronto’s Parkdale neighbourhood. The money still keeps coming in. It’s astounding. It tells me that there are people who are affected by the overdose crisis and want to contribute but don’t know how. It may be a small thing that they’re doing—but it’s also a big thing. We’re saving lives, and the more we can grow, the more we can save.

Jennifer Johnston

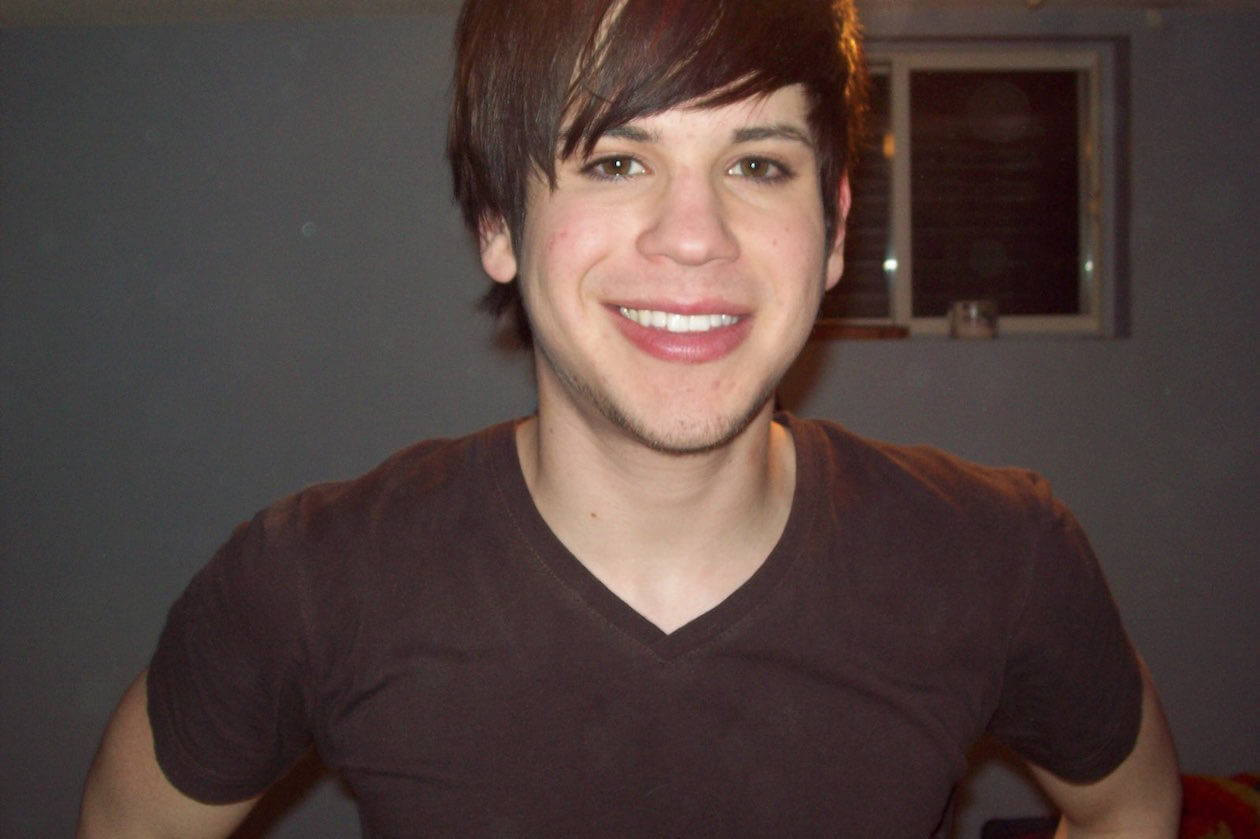

Even at eight years old, my son Jonathan knew he wanted to be a chef. At first, I never let him help me cook—I had five children, and it was always a disaster when the kids were in the kitchen. Still, growing up, Jonathan watched cooking shows with his dad, and he would always ask for new supplies every Christmas and on his birthday. One Christmas, when he was about twelve, he asked for a set of ramekins so he could make crème brûlée. It was the first thing he ever made that made me go wow; here’s this little boy, not even a teenager, and he’d just made something that tasted like a dessert from a fancy restaurant.

When he later moved to Toronto to attend one of George Brown’s culinary programs, I knew he was following his dream. I never suspected that he’d start using heroin there.

When he called me and confessed, crying, saying he wanted to stop, I believed he could do it: he was so driven and had such a bright career ahead of him. Fentanyl wasn’t on my radar at all. I was not afraid enough. This is something that’s going to haunt me for the rest of my life. We ran out of time. Of course, I was shocked and appalled and worried and concerned. And it caused me many sleepless nights. But, for a time, Jonathan did seem to have it figured out. Shortly after he told me about his drug use, he got a job working with Claudio Aprile, one of the judges on MasterChef Canada, at Origin restaurant, which is now closed. Jonathan was just so talented. I thought he might be okay after all. His father and I didn’t tell any of his siblings or anyone close to us—he didn’t want them to know, and at the time, we agreed it was best to keep quiet about it. I thought we could save him with love. And it just doesn’t work that way with this crisis.

Then, in April 2016, when Jonathan was twenty-five, I got a phone call from his girlfriend, who’d been told he’d missed two shifts at work. His father drove from Hamilton to Jonathan’s apartment in Toronto, and when there was no answer at the door, he reported him missing to the police. We later found out that Jonathan was already dead. He had collapsed on a sidewalk at the intersection of King and Yonge streets at 3:23 a.m. days before. A passerby had called 911. The first responders who answered the call did not have naloxone; they could have saved him. He had a clipboard for the next day’s menu with him. When the coroner tested what Jonathan had thought was heroin, they discovered it was almost pure fentanyl.

Jonathan was my eldest child, and telling his siblings—who were just hearing for the first time that he used opioids—was as hellish as hearing the news myself. If I could go back in time, I would not keep his use a secret. It needs to be brought into the light. Looking back, I think he was ashamed, and we all unconsciously fed into that. The stigma against drug users is debilitating and one of the biggest barriers to recovery. My grief remains very, very complicated. I put so much blame on myself: What could I have done differently?

Today, I feel as if sharing Jonathan’s story is my life’s purpose. How wonderful it would be if all our kids did not die in vain. I believe their stories are instrumental in preventing more deaths. People need to know what this crisis is costing us.

Judith Rossman

My youngest son, Noah, was academically gifted. He was placed in the program in grade four, and he loved it. He was the kind of kid who could sit for hours reading an encyclopedia, opened to any page at random. He wanted to learn as much about everything that he could. He was curious. He continued to excel in high school—at least academically. Noah was also gay, and I started a gay-straight alliance in our area; he knew his sexuality was never a problem for me. But I didn’t find out until after he graduated that he was bullied mercilessly in high school for it. During those high-school years is when he started experimenting with drugs, including heroin. He later told me that he would rather be known at school as the drug addict than as the fag.

But at the time, I had no reason to suspect anything was seriously wrong. His grades remained high, and even though his social group was also using, they all also had university scholarships and likewise excelled academically. Later on, I came to think of them as a new kind of addict, the bright and young. When I found out what was really happening, I realized I had the crisis all wrong: it isn’t just people on the streets who are using opioids; it’s everybody.

Noah’s drug use finally came to light the day he was supposed to register for classes at Brock University. I was going to drive him, but he wasn’t getting off the couch to come with me, and he seemed really out of it. It wasn’t like him at all. Eventually, I got him in the car and dropped him off at the university. Knowing there was a problem, and not knowing how to handle it, I went straight to the Community Addiction Services of Niagara offices and asked to see a counsellor. I phoned Noah, and he agreed to come with me that afternoon. Noah didn’t want to have this problem; he took every chance he had to get help. That day, he told me he was using OxyContin. He couldn’t bring himself to tell me about the heroin then, but he did shortly after.

From there, Noah told me he wanted to go on methadone. When we first went into the clinic, Noah was turned away because he didn’t have any opioids in his system; he was trying to stop. But he knew it was only a matter of time before he started using again. This is where moms doing crazy shit comes in. I gave him $20 and drove him to get some drugs; he started methadone the next day.

After a while, it didn’t work. Over the next couple of years, Noah was in and out of rehabilitation programs and also Narcotics Anonymous. He always did so well in rehab. I still remember seeing him after he finished one program for the first time and thought he’d beaten his drug use—his eyes kind of sparkled. The more he used and then relapsed, though, I slowly saw that light go out in his eyes. In the end, there wasn’t that spark of the confident Noah I knew. As time progressed, he had less faith in himself that he was going to be able to conquer this.

Noah died in 2012, in our house. He was actually going through a really good stretch of not using. The day before, we’d had this amazing conversation, and at the end of it, he pulled me in close, gave me a big hug, and told me that he loved me. The next morning, I came downstairs and he was on the couch. It looked like he was sleeping with his laptop on; I’d seen him in the same position millions of times. But this time, I knew something wasn’t right. And then I saw the syringe on the couch. The nightmare began from there. It was only a week before his twenty-second birthday.

The autopsy later revealed it was heroin—just a small amount. I’ve since met so many more parents whose children have died from opioid poisoning, and fentanyl in particular. We see these people who we love, who are so wonderful, just disintegrate in front of us. And there’s nothing we can do.

Today, I’d tell anyone going through this to support their children. Even though at times it may be hard to recognize your child, you must remember that the loving kid you once held close is still in there. Tell them that you love them. Let them know that the struggles they are experiencing—the ones they think are only happening to them—are, right now, happening to someone else.