In a Star Trek: The Next Generation episode called “The Hunted,” Captain Jean-Luc Picard makes a port visit to Angosia III, an advanced and peaceful society seeking membership in the United Federation of Planets. The Angosians have recovered from a devastating war waged by an aggressive enemy. But the crew discovers that the victory came with an ethical trade-off: with their survival at stake, and no established military traditions, the Angosians used biochemical manipulation and radical psychiatric techniques to create an elite warrior class.

Once peace was restored, these Angosian warriors transformed from heroes to outcasts. The very qualities that had made them ruthless killers became liabilities when they returned to civilian life. And so these veterans were banished to a nearby moon, which effectively became their prison. At one point, an enhanced Angosian combat vet tells a Starfleet officer, “My improved reflexes have allowed me to kill eighty-four times. And my improved memory allows me to remember each one of those eighty-four faces. Can you imagine what that feels like?” Almost thirty years later, with the real experience of 9/11, the war in Afghanistan, and the invasion of Iraq behind us, that sounds a lot like PTSD.

The most prescient science-fiction stories reflect something vital about the world we inhabit. The Earth is a far more violent place today than the fictional world of Angosia III ever was. But that doesn’t mean we don’t confront the same problems. The New York Times recently published a report on the soldiers who find it most difficult to reintegrate into civilian life. “I don’t even leave my house much,” says former US Marine Jeff Ewert. “I’m scared not because I’m an über-killer or anything. I just minimize my exposure because I know how easy it is to cross that line, to act without thinking.”

Some of the soldiers who spoke to the Times have been deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan on as many as five tours of duty and by necessity have adapted themselves to the brutal realities of counter-insurgency warfare. In the field, the qualities of hyper-alertness, rapid decision-making, and thriving on stress are what keep them alive. In workaday civilian life, such qualities can drive a veteran mad.

Many of the triggering situations these soldiers encounter are surprisingly humdrum—disproportionate responses to such everyday offences as littering or being cut off in traffic. Typically, such breaches of the social contract are mere annoyances, not life-and-death concerns—unless you are coming from a place where soldiers and civilians share common space, and danger could be lurking at every turn. Think of a real-life Jason Bourne who has memorized the location of all the exits and casually evaluated the potential threat posed by fellow patrons—all by the time he sits down at a booth in a diner.

“During my time in Sarajevo, my mind had clicked into survival mode,” wrote PTSD sufferer Fred Doucette in his 2015 memoir, Better Off Dead. “The simple reaction of fight, flight, or freeze is what I [heeded]. Caring, loving, feeling, and happiness had gone. Life had turned to black and white. I was physically back in Canada, but my mind was still on the streets of Sarajevo.”

It should be noted that the majority of combat veterans who return from war are able to reintegrate into society. But some types of soldiers have lower success rates than others. Researchers who recently studied nearly 500 suicides among US Army personnel, for instance, found that soldiers in two specialties operating at the heart of counter-insurgency warfare—infantry and combat engineering—were significantly more likely to commit suicide than those in other specialties. These soldiers were unusual in another way, too: across the Army as a whole, a soldier is more likely to kill himself when deployed abroad—separated from loved ones, in a potentially hostile environment—or upon return from deployment than when stateside. Among infantry and combat engineers, this pattern is reversed.

Given the full-scale meltdown of large parts of the Middle East and Central Asia, today’s career soldiers are more likely than their predecessors were to be exposed to a slew of long, inconclusive, low-intensity conflicts. Going forward, the forces that fight these battles will be smaller and more specialized than the sprawling armies that won the large wars of the twentieth century. We will train these select professionals harder, equip them better, and deploy them on longer, repeated tours of duty. But despite all of this investment, we still have relatively little idea of how to reorient them when they finally come home.

In some cases, this transition may not even be possible. As a combat-stress expert told the Times, “Turning off this hyper-hardwiring after returning from a deployment is not an automatic function of the brain. We have virtually no science to guide us in managing these instincts.”

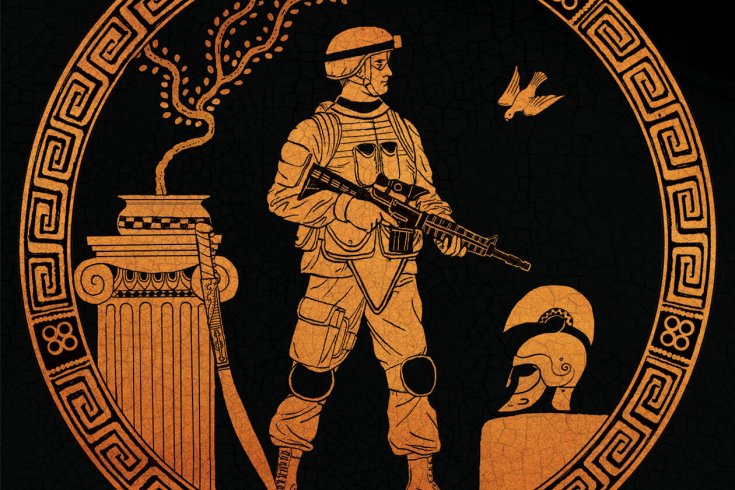

Part of the problem is that the nature of war has changed more quickly than we have. As military historian Victor Davis Hanson notes, the central act of Western warfare since the time of Ancient Greece had been the epic, one-off battle between masses of opposing infantry: because such conflicts were decisively resolved, surviving citizen soldiers could return home in time for harvest. Modern wars against terrorists and paramilitary groups, by contrast, can drag on for decades and require a professionalized breed of high-tech soldier, who in turn suffers a more diverse array of psychic wounds.

Changing attitudes toward warfare may also contribute to a transformation in the way we see the fighting class more broadly. During World War II, it wasn’t unusual for a farmer or mechanic to go marching off with a gun and then return to his tractor or factory a few years later—the industrial-age equivalent of the Greek hoplite coming back to his fields. Even if the concept of “shell shock” was to some extent familiar, most war movies from that era show Allied soldiers as farm boys who glide easily back into a life of soda shops and drive-in movies. But statistically speaking, soldiers now constitute a much smaller part of the population than they did during the First or Second World Wars. They have become, in our imagination, members of a distant, fabled warrior class—near-superhumans, different from the rest of us in all but a genetic sense.

If the therapies provided by society cannot help these warriors transition to civilian life, the only solution may be, in effect, to transform the bugs of the current system into features: the armies of the future may eventually be staffed by ultra-elite soldiers who enlist without any expectation of ever reintegrating into normal civilian life. It’s doubtful that the sort of Angosian scheme put forth in Star Trek: TNG would ever be adopted as explicit policy, of course. (And the increasing use of robotics in war may make some of these problems go away on their own. If that were to happen, some of the best ways to imagine a future reality might come from the world of fiction: Daniel H. Wilson’s bestselling 2011 novel, Robopocalypse, for example, describes a US Army that sends armed, autonomous robots into Afghan towns and villages on patrols.) But this “warrior class” model has appeared before in history. The Ottoman Empire, for instance, would train kidnapped Christian boys to become elite infantry units known as janissaries, which constituted their own distinctive class within Ottoman society.

Needless to say, no one is proposing such extreme measures of recruitment—or suggesting that these elite specimens be exiled to other realms when their military service to Western nations is at an end. But we may wish to consider longer terms of enlistment—and greater financial incentives for those who remain in the military for their entire working career.

At the very least, our recruiters should be upfront with those who enlist in the most demanding and brutal of front-line military specialties: the most horrible job on earth may become the only one they will ever be able to truly enjoy.

This appeared in the September 2016 issue.