In Old Crow, teenage students at Chief Zzeh Gittlit School, with land guardians and Elders, climbed onto snowmobiles and travelled 500 kilometres along a traditional route called Dagoo T’aii. On the journey, they harvested caribou and shared stories. In Whitehorse, a two-hour flight south, preteen students at Takhini Elementary created hunting bags, cutting and stitching canvas and deer leather with the guidance of First Nations knowledge keepers.

These two Yukon public schools—along with nine others—are members of the territory’s First Nation School Board. Formed in 2022, the board shares authority with the Yukon government. It follows British Columbia curriculum, as all Yukon schools do, but the programming, assessment methodology, and delivery are informed by First Nations world views. While some of the schools are in First Nations communities, First Nations identity is not a requirement for students or teachers.

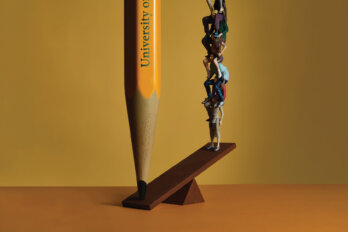

A landmark document called “Together Today for Our Children Tomorrow” identified the need for a First Nations school board in 1973. “We were taught in such a way that we were forced to give up our language, our religion, our way of life,” wrote the Council of Yukon Indians (now the Council of Yukon First Nations). A group travelled to Ottawa and presented the document to the federal government, which began land-claims negotiations in the territory. Until curricula included history predating the Klondike Gold Rush and information about First Nations ways of life, they argued, First Nations students would always be at a disadvantage in the classroom. The document encouraged on-the-land teaching: “The whole Yukon is our school. In the past we learned from our surroundings.”

Fifty-two years later, dismal results bear out that truth. According to the Yukon First Nation Education Directorate, between 2015 and 2023, only 47 percent of Indigenous students graduated high school, compared to 73 percent of non-Indigenous students. This finding came after two reports by Canada’s auditor general, in 2009 and 2019, criticized the Yukon government for not adequately addressing the disparity. (Nationally, too, these gaps exist: Indigenous people graduate high school and postsecondary at a lower rate than the non-Indigenous population does.)

Improving educational outcomes starts with embedding First Nations world views across subjects, incorporating First Nations language instruction, and inviting Elders into the classroom. This will look different at each school, with committees to tailor operations to the specific community. In Haines Junction, located an hour and a half west of Whitehorse, a local First Nations language teacher partnered with a high school teacher to co-teach grade eleven and twelve classes. Instead of dividing subjects like science and social studies into separate periods, they integrated them into a cohesive, interdisciplinary approach. Six hours northeast, at Ross River School, elementary students studied math in the woods, pretending to be forest biologists conducting plant surveys as they learned how to calculate and represent data. The idea is to help children understand that everything is connected.

As Melissa Flynn, executive director of the First Nations School Board, puts it, First Nations world views go beyond “beads and bannock.” Instead of following a top-down hierarchy, the board’s organizational chart places students at the centre, surrounded by parents, teachers, support staff, and the broader community. For instance, when Flynn started her job, she knew she wanted to improve the literacy skills of First Nations children. She spoke to experts, speech language pathologists, and teachers in the territory—as well as communities—about what needed to change.

That led to the board’s decision to pivot from what’s known as “balanced literacy” to a “structured literacy” approach. In balanced literacy, students are taught to look at cues—pictures on a page, first letters of a word—and think about what word makes sense in the context to determine what it says. With structured literacy, teachers introduce the sounds that make up words and encourage kids to sound them out.

“My daughter was walking around going ‘c-c-a-a-t-t,’ and then she was able to turn that into ‘cat,’” said Jason Van Fleet, whose child attends Chief Zzeh Gittlit School. “She is reading words, and she’s only three years old.” This approach—focusing on kids’ strengths and meeting them where they’re at—exemplifies First Nations world views. The board is also creating books, featuring local stories, that break down sounds for young learners.

In November, the Yukon News reported that students at three of the board’s schools now read within an average range, as defined by North American standards, compared to those at only one school when the board began in 2022. The board’s 2023/24 report also states that students’ standardized test results have improved by up to fourteen scores. “When Yukon First Nations learners see themselves reflected in the learning and see that their language and culture is being upheld, we find that their attendance and their satisfaction and happiness with school changes,” said Erin Pauls, the board’s director and land and language team lead.

Flynn argues that non-Indigenous children also benefit from learning through a First Nations lens. Understanding the interconnectedness of all things can help them become more engaged citizens and develop a deeper awareness of the place they call home.

Nelnah Bessie John School joined the board in 2022. Located in Beaver Creek, a community of about eighty people five hours northwest of Whitehorse, the school soon introduced a new schedule for the year. Students start in early August, attend classes for four to six weeks, then break for one to two weeks—all year long. The decision was informed by the views of local parents and the White River First Nation, the intention being to give families time to go hunting, fishing, and trapping.

For Colleen Joe-Titus, a Champagne and Aishihik First Nations citizen who chairs the St. Elias Community School’s committee in Haines Junction, this is about doing things differently, with respect. “Many of us know our history of residential schools or mission schools—which, you know, my parents both went through that,” she told the CBC. “We have an opportunity now to go down a new path together.”