On August 24, 1914, as artillery shells pounded Western Europe, a twenty-seven-year-old veterinarian stopped in White River, Ontario, on his way to war. Later that day, Lieutenant Harry Colebourn jotted down a few words in his diary: “Left Pt. Arthur 7 A.M. On train all day. Bought bear $20.” He called her Winnie, after his adoptive city of Winnipeg.

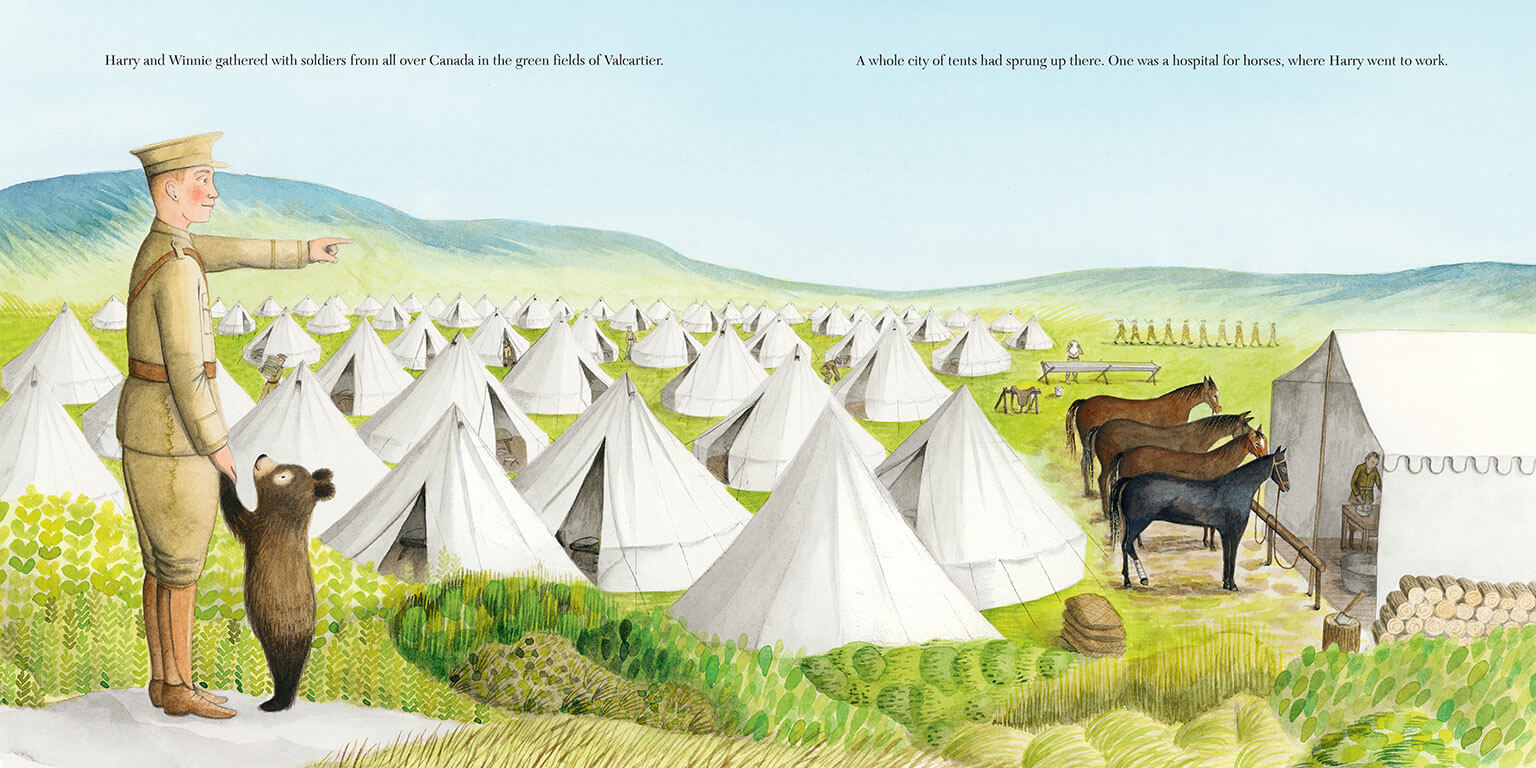

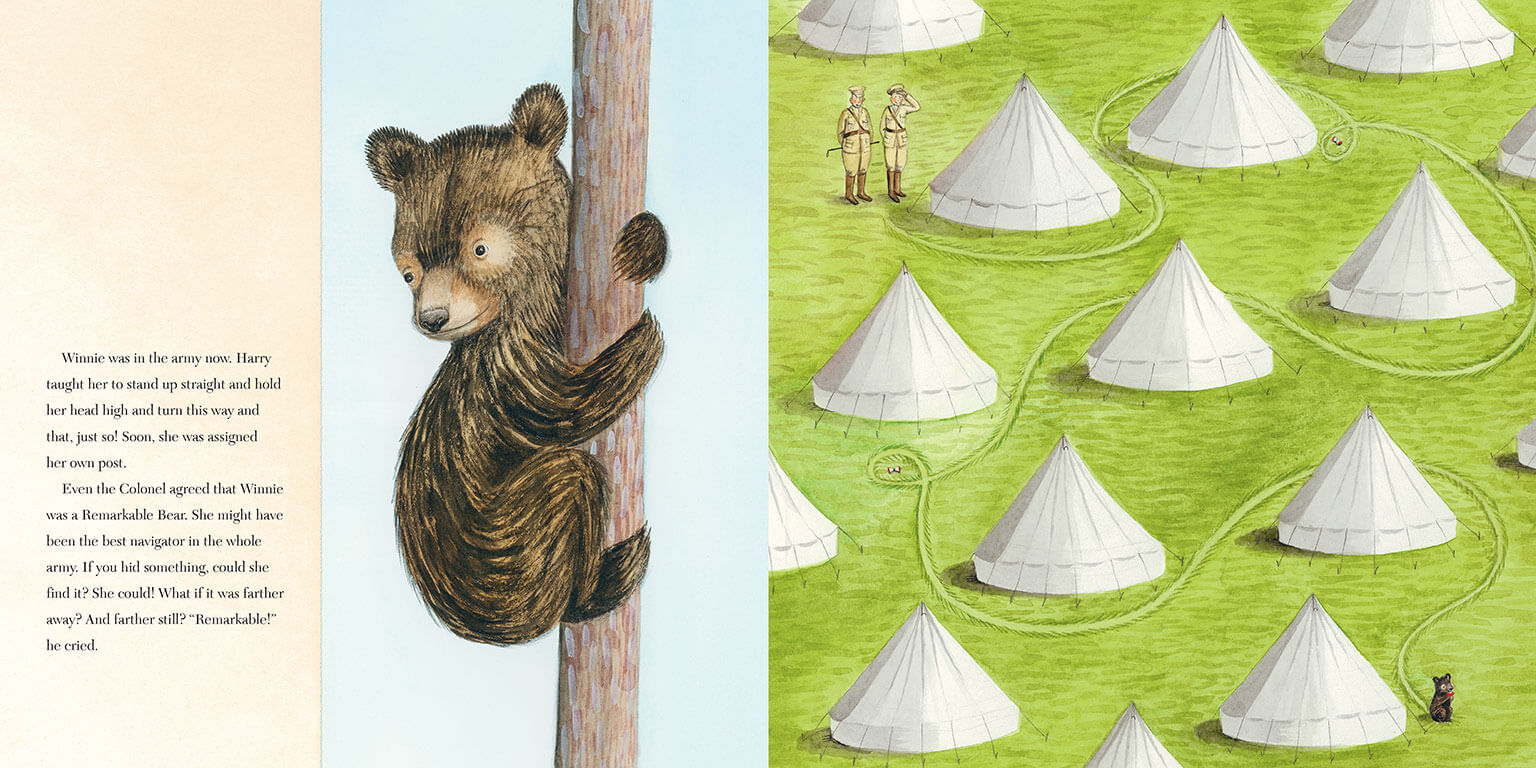

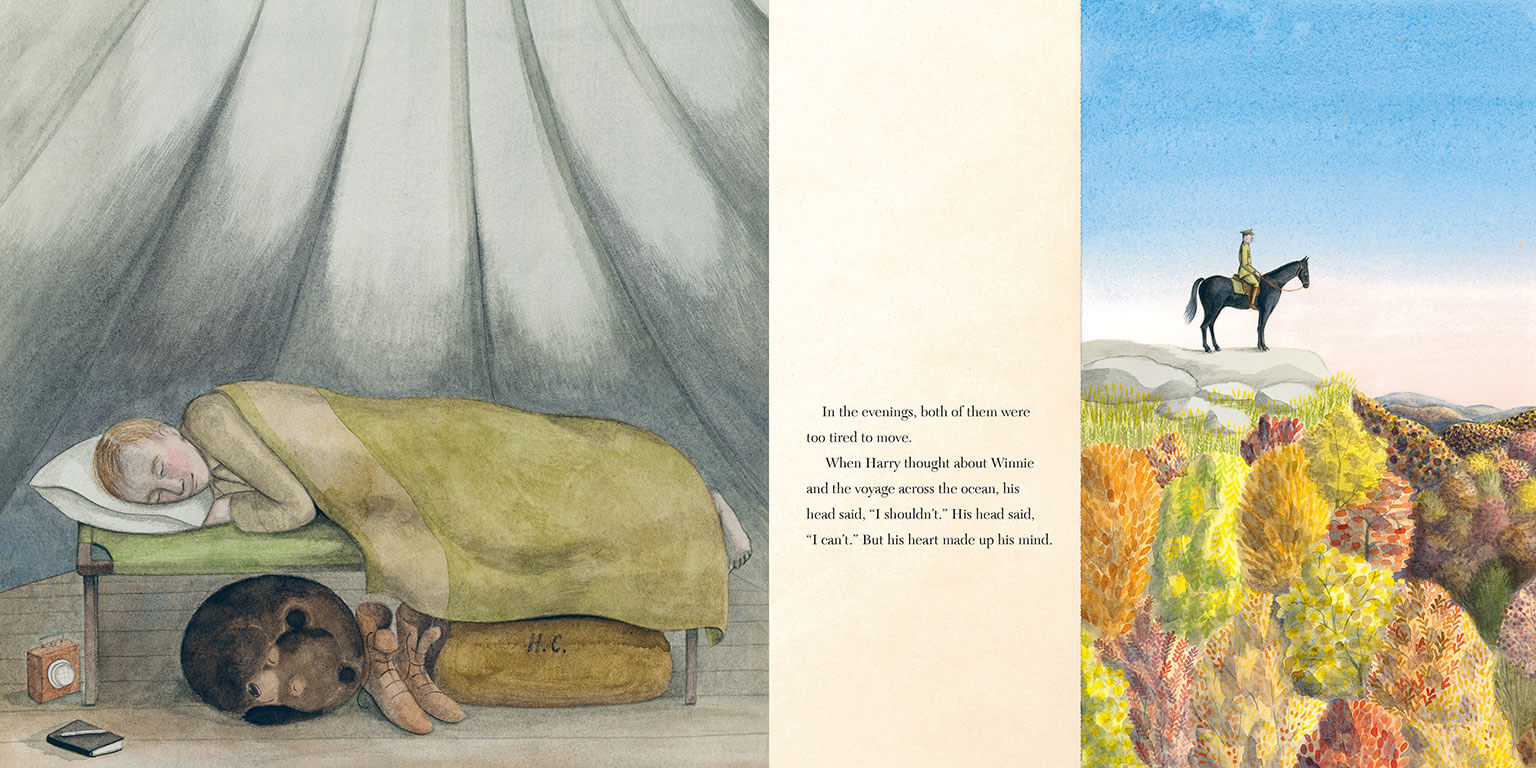

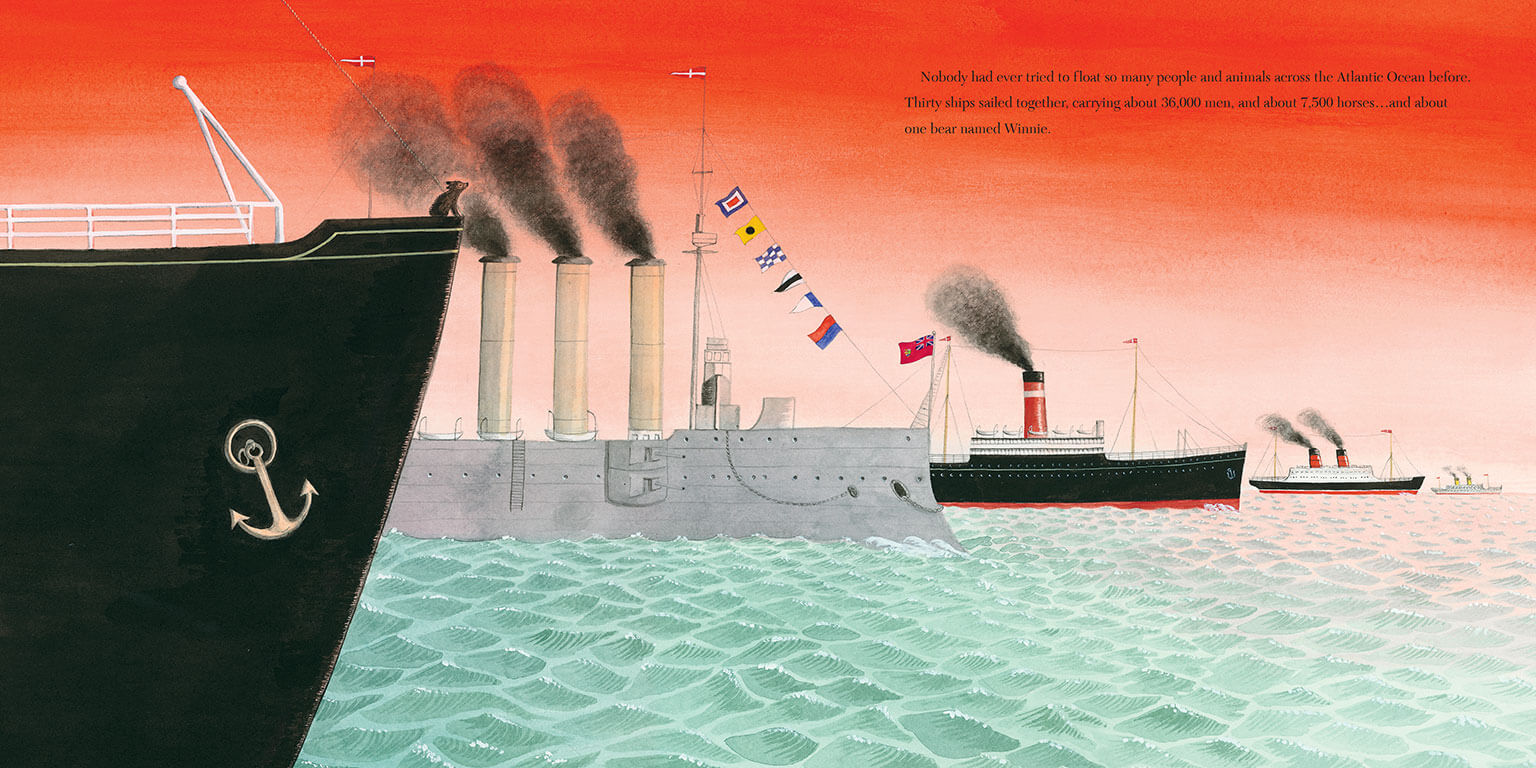

Before sailing across the Atlantic Ocean with Colebourn, Winnie was a beloved pet and regimental mascot at the First Canadian Contingent’s makeshift training grounds in Valcartier, Quebec. She stayed with the Second Canadian Infantry Brigade all the way to England’s mud-soaked Salisbury Plain. But when Colebourn was called to the front that winter, he was forced to leave her with the London Zoo. Across the English Channel, his diary entries became terse and dark: “Town is being shelled to pieces. Many men & horses killed. Shell bursts almost at my feet.” At Ypres, Belgium, he witnessed asphyxiating clouds of chlorine roll over the French and Canadian lines as old men fled the town with their wives on their backs. Despite all he saw, Colebourn never fired a shot; like many who were changed by the war, he devoted himself to caring for others, treating animals just a stray shell away from the front line.

One of the most famous images of Colebourn and Winnie was taken shortly before the former left for France. It shows the him smiling as he feeds the cub. On leave, he would return to London and visit the bear that had become a light for him through the campaign. On the back of the photograph, he wrote, “Winnie is now on Exhibition at the Zoo in London but is coming back to Canada with me someday.”

Now, more than 100 years later, Colebourn’s great-granddaughter Lindsay Mattick has brought Winnie home with a children’s book—the bear’s true story. Mattick, who spent her childhood summers with her family on the shores of Lake Winnipeg, has done much to ensure Colebourn isn’t forgotten. She produced a documentary about her family history for CBC Radio in 2003, and in 2014 she helped organize a centenary exhibit at Ryerson University in Toronto, which included Colebourn’s wartime diaries and photographs. Her new book begins as she puts her son, Cole, to bed. (The work is dedicated to the young boy, who is named for his great-great-grandfather.) Illustrated by Sophie Blackall, what unfolds is the story of a chance encounter and a compassionate gesture, set against the backdrop of global conflict.

Winnie’s latest journey to the page was itself intergenerational. In 1987, the Calgary Herald erroneously wrote that the bear had belonged to an Edmonton regiment. Mattick’s grandfather, a historian and archivist, felt compelled to set the public record straight. “Our family didn’t talk much about the story,” Mattick says. “But after that newspaper article, my grandfather said, No, that was my dad’s bear. She’s named after Winnipeg.” A flurry of media attention followed, as did a statue in the Matticks’ hometown, where Colebourn and Winnie are immortalized standing with hand and paw clasped in Salisbury Plain.

For Mattick, the story epitomizes a kind of compassionate innocence, showing how small actions and “proceeding with love” can have large, long-term consequences. There is another moral: letting one story end means another can begin. Ultimately, Harry Colebourn couldn’t bring Winnie home when he returned to Canada in 1920. The bear stayed in London, where one day she met Alan Alexander Milne and his son, a boy named Christopher Robin.

This appeared in the November 2015 issue.