Mark Ruwedel leans coolly back against a wall with his long white ponytail swept to one side. We’re sitting on a bench inside downtown Toronto’s Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art, surveying the beautiful pieces surrounding us. A media preview of the Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival has just come to its end. I’ve caught up with Ruwedel to congratulate him on winning the 2014 Scotiabank Photography Award, a coveted prize that includes $50,000 in cash, a solo exhibition next spring, and a book deal with Steidl, the famed German art publisher.

“I haven’t even come to terms that I’ve won this thing yet,” the veteran shooter concedes with a shrug. “Obviously, I’ll be more visible [now]. It’ll maybe open some doors that I didn’t even know were there. But what I’m really thinking about is that in two days I get to go back into my dark room and get some things done.”

Ruwedel, a Pennsylvania native, stumbled upon photography in the late ’70s, while doing his undergraduate degree for arts and painting at Kutztown State College (now known as Kutztown University of Pennsylvania). According to him, the photography wing was where the most interesting students hung out, which inadvertently sparked his passion for the craft. From Kutztown, Ruwedel moved to Montreal to pursue graduate studies in fine art photography at Concordia University.

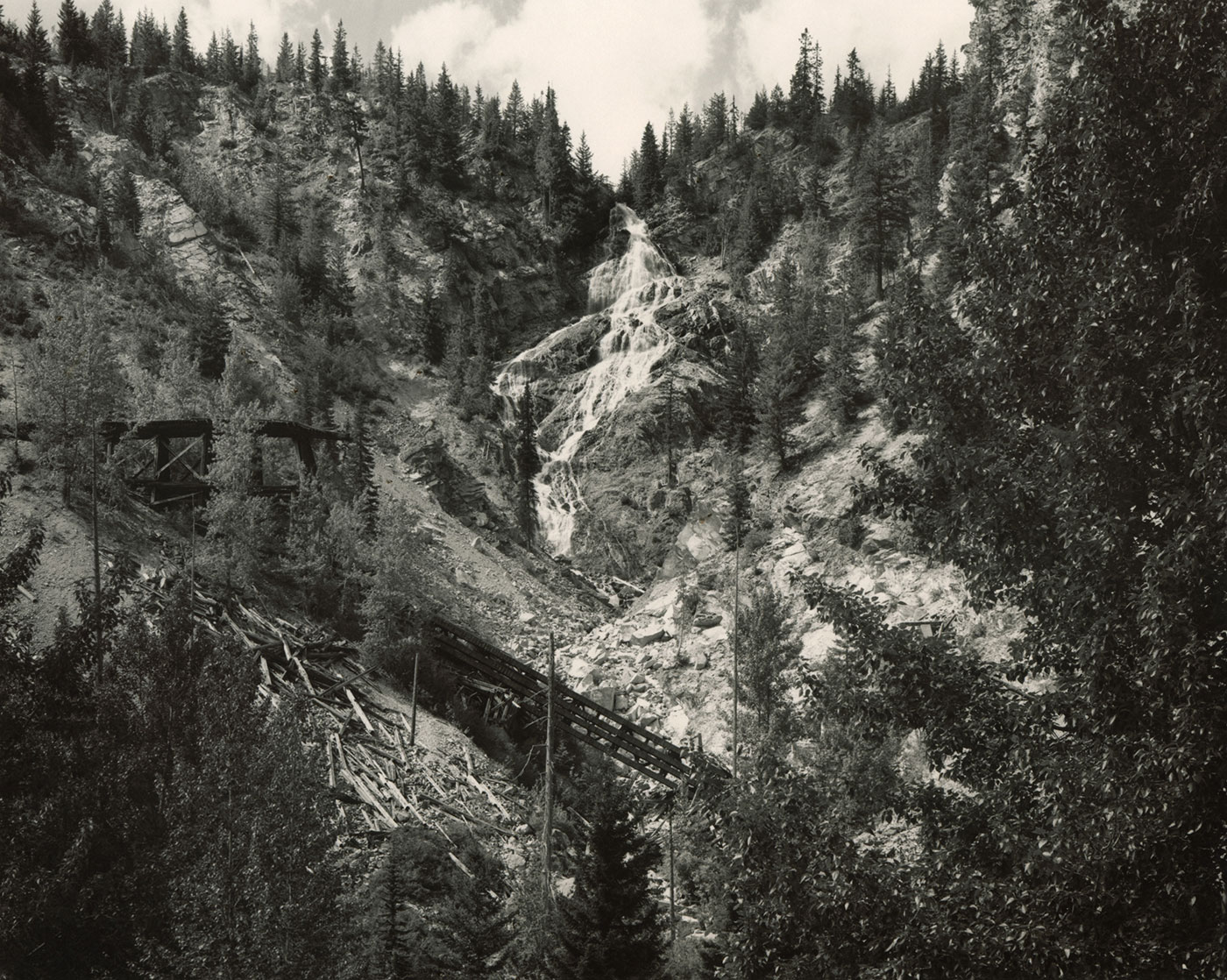

“We still believe photographs,” Ruwedel says. “I don’t think I’m a documentary photographer, but it’s that kind of transparency of reporting—an accurate description of what’s really there.” He believes his art, which focuses mainly on landscape, involves a method of storytelling not unlike documentary film.

“Landscape is a way of talking about people without pointing cameras at them,” he says. “The [very] idea of landscape suggests human history because there’s no landscape in nature, only land. Landscape already implies a frame, design, et cetera. It’s a way of thinking about history and all those big things.”

Observing Ruwedel’s lifetime of labour, one finds that deserts in particular are a recurring theme. “I have a great fondness for desert ecologies,” he admits. “[It’s] the landforms. The clarity of the light because deserts have a very arid atmosphere: it makes edges sharper, distances collapse in all different ways. There’s also something about the readability of desert landscapes. Stuff stays on the surface a long, long time. The stuff just sitting out there has been sitting for 10,000 years because nobody’s been by to disturb it.”

Edward Burtynsky, world-renowned landscape photographer and inaugural chair of the Scotiabank Photography Award’s jury, is quick to praise Ruwedel. “I think Mark’s amazing. He’s certainly proven over a thirty-plus-year career that there’s a consistency: a vision, concept, and craft, and all these things that are present in the work,” Burtynsky tells me. “That is what the award wants to celebrate, this kind of excellence over a long period of time.”

Ruwedel’s work, Burtynsky observes, pivots around the notion of how humanity’s past and present has marked the landscape. “He’s brought those marks forward, and the titles”—Ruwedel favours plain-spoken names like Antelope Valley #44B, Tonopah and Tidewater #25, and Deep Creek #2—“always express this passage of generations long ago.…Landscape photographers are looking at histories and looking at how man has changed the [Earth]. Often times as a kind of critique of our expansion and the pushing back of nature.”

Oddly, Ruwedel says he is not a great lover of nature. “The kind of photography I wanted to do had something to do with being outside. Not just literally outdoors—but being in the world rather than the studio,” he explains. And while it might seem like taking pictures of nature is a walk in the park, Ruwedel bluntly dismisses that notion. “It’s hard work. It’s not my vacation,” he says.

Good for him, then, to reap the benefits of so much labour.