Last October, with the demise of esteemed Vancouver publisher Douglas & McIntyre in the news, Dan Wells received an email from a Toronto critic. Wells is himself a publisher, and had just mentioned on his website that his intrepid eight-year-old firm, Biblioasis, would soon produce and sell its books out of a building he had purchased in downtown Windsor, Ontario. But the email was not about the new building. “If this keeps up,” the critic joked, “by next spring you’ll be the third biggest publisher in Canada.”

These are dog days in the book business, and some are pronouncing them end days as well. The “dream,” as headlines would have it, of a vigorous independent publishing industry has died, felled by a cabal of assassins. Depending on who is pointing the finger, they include the rise of ebooks and Amazon.ca; too many titles for too few buyers; the routing of supportive independent booksellers by Chapters/Indigo; the impossibility of competing with deep-pocketed multinational publishers for authors and market space; and, more cosmically, the atomization of everything, especially attention spans, in our digital world.

The announcement that D&M would seek bankruptcy protection seemed irrefutable evidence of cultural murder most foul. The firm could boast forty years in the trade, and had enjoyed such a string of recent successes that co-founder Scott McIntyre was set to receive the International Festival of Authors’ inaugural Ivy Award for his “passionate representation of Canadian publishing.” If D&M—which had once shared top billing for passionate representations with the likes of the late Key Porter Books and Stoddart Publishing—could not make it, who could? Of the older indie Canadian houses with national profiles, only Toronto’s House of Anansi is yet among the quick.

Earlier in 2012, McClelland & Stewart, once the nation’s independent publishing flagship, had been officially swallowed by the German firm of Bertelsmann, joining an extended “family” that already comprised the Canadian operations for Knopf, Doubleday, and Random House. Not content with 40-plus percent of the market, Bertelsmann added salt to the wound of the collapse by formalizing a merger in October with its only rival for supernal publishing supremacy, Penguin Books UK. Penguin Random House was formed to build a federation in the unfolding global war with online publishing competitors, but it felt to some Canadians like the premature desecration of the almost-corpse of our domestic book business.

All of this industry bloodletting and anxiety has not affected the consumers of books. They remain strong in number—sales in Canada have increased steadily over the past decade—but seem distracted from, or even indifferent to, the matter of who writes and publishes the titles they want to read. This was not always so. Once upon a time, Canadian readers, authors, publishers, and booksellers constituted their own federation. The front was dubbed CanLit, and it promoted a proud cause: growing a native book industry out of near-nothingness in the face of a rapacious American culture and imperialist might—an enemy of Goliath stature and, it was hoped, mental sluggishness. With enough practice, David’s slingshot could not help but fell the brute.

The era of cultural nationalism came and went long ago. Understanding just how long, and how much has transpired since then, may help console those feeling bruised and ill treated by the legacy erasures of recent times. The problem, appropriately enough, may lie with the stories we still cling to. Many in the business of Canadian publishing in 2012 were themselves either proxy Davids in that mythic battle, or were reared on the grand tale. They, and we, cannot quite abide the loss of a narrative about ourselves as cultural citizens that is, frankly, more tidy and reassuring than any we might try piecing together out of our messy, destabilized, clearly transformative age. No harm in preferring the old stories and even the old ways—unless, that is, you are meant to be in the business of trying to tell (and yes, sell) new ones.

CanLit was hatched in Kingston, Ontario, in 1955, just four years after the Massey Commission famously asked, “Is it true, then, that we are a people without a literature? ” At the first Canadian Writers’ Conference that July, the respected editor John Gray mused about “the conditions under which Canadian literature might come into existence.” At the time, there were only a few publishers and a handful of literary magazines. Some forty bookstores were scattered across the country, and almost no Canadian works were being taught in schools or universities. As for supporting nascent publishing ventures, the Canada Council had yet to arrive on the scene. (The Governor General’s Literary Awards date back to 1937, but in 1955 they had zero monetary value and about an equal profile.) The first instinct for some young writers, such as Montrealers Mavis Gallant and Mordecai Richler, was to get out. For others, it was to stay home and start pushing a big rock up a steep hill. As Roy MacSkimming observed wryly in his classic study of the business, The Perilous Trade, “Things could only improve.”

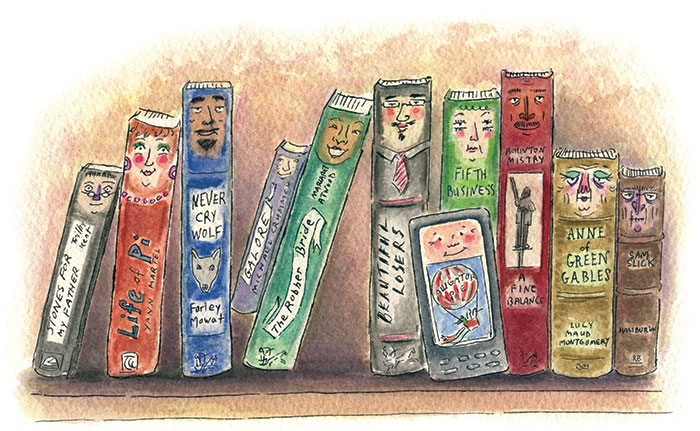

And they did. If the plan for a national literature, by necessity theoretical and inorganic, was incubated in Kingston, its natural commercial birth may have occurred twelve years later in Toronto. That was when Jack McClelland invited some 350 tastemakers to a splashy launch of Beautiful Losers, the controversial second novel by poet Leonard Cohen, by far the country’s hippest literary cat. The date was March 29, 1966, and the location was the then trendy Inn on the Park in midtown. The invitees were a who’s who of Canadian literature past, present, and future: Pierre Berton, Austin Clarke, Adrienne Clarkson, Robertson Davies, Timothy Findley, Northrop Frye, Robert Fulford, George Grant, Peter Gzowski, Marshall McLuhan, Gordon Sinclair, Harold Town, and Scott Young, to name a few.

Cohen had misgivings about the gathering, but McClelland, who had made over his father’s cautious firm into the largest and most adventurous Canadian publisher, decided he had the right book, the right author, the right city, and the right moment to issue a de facto proclamation. “I think the Toronto party should be used as a springboard,” he wrote in a staff memo. He meant for Beautiful Losers, of course; but as a declaration, an assertion, the occasion also served as a springboard for Canadian writing.

Authors, publishers, sellers, and academics were soon agitating door to door to get local books produced, funded, promoted, and protected, as well as into libraries and onto course syllabuses. The movement—which indeed defined itself as a David to the Goliath of American imperialism, and, less advertised, the colonized Canadian mindset, with its impulse to presume all things foreign superior—had many champions knocking on many doors. Regardless, “Among the bulk of readers at that time,” Margaret Atwood would later recall of homegrown literature, “it was largely unknown, even in Canada, and among the cognoscenti it was frequently treated as a dreary joke, an oxymoron, a big yawn, or the hole in the non-existent doughnut.”

Atwood was just thirty-two in 1972, the year she personally invested literary nationalism with an underlying argument that was neither dreary nor yawn inducing. Her Survival: A Thematic Guide to Canadian Literature was less a rendering of the zeitgeist than a willed gestalt therapy session, pushing for a unified and proscriptive diagnosis of the collective literary dilemma. With catchy terms and clever stages—the four (colonized) “victim positions” eventually birthing (emancipated) “creative non-victims,” which shortly became axiomatic among the book’s followers—it made Atwood, along with her soon-to-be husband Graeme Gibson, the attractive faces of the movement, as well as its biggest targets. Survival sold an improbable 150,000 copies for House of Anansi, which had been founded just five years earlier.

Boosting the odds for literary “survival” in the vast and complex space, both geographic and psychological, that defined Canada was honourable spadework, clear of purpose and direction. Mordecai Richler may have enjoyed taking shots at rampaging Canadian nationalism and state-sponsored mediocrity, but he both benefited professionally from them, and, by returning to Canada for good in 1972, demonstrated how happily the country had changed in just two decades. Still, it was fitting that the free trade debates of the late 1980s pitted the two titans against each other, albeit superficially. In November 1987, Atwood told the Parliamentary Committee on Free Trade that the only position the US had adopted toward Canada was “the missionary position, and we were not on top.” Richler confessed to the committee that, as far as protecting Ontario wines from their American counterparts went, “There is only so much I am prepared to drink for my country.”

Free trade became law in 1989, and the era of cultural nationalism wound down. People got older, grew tired of the sounds of their own agitations, moved on to other projects. A quarter century is an impressive run for any movement, and much that was lasting had been achieved. Canada, surely, could never again be “an unknown territory for the people who live in it,” as Atwood diagnosed in Survival. It had been made known to itself by its authors, and if certain seminal works of the era feel dated, no surprise; the country has since evolved one- or twofold. And there, perhaps, lies the deeper problem, and challenge, for Canadian publishers in 2013.

Survivalwas among ten titles reissued last autumn by House of Anansi as part of its A-List series. A mixture of older and newer books, it is a nod to the cultural nationalism era, minus any nostalgia. Anansi likely hopes readers will collect the editions, if not for old times’ sake then to register the publisher’s longevity as a producer of dynamic Canadian work. It undertakes the A-List in the aftermath of the mixed success of a far more ambitious attempt at in effect telling Canadians about the territory they have long inhabited. Between 2008 and 2011, Penguin Canada issued eighteen volumes in its Extraordinary Canadians series, each a short thematic biography of a significant figure. Modelled on the international Penguin Lives, the project felt at once long overdue and like something of a throwback. “How do civilizations imagine themselves? ” asked series editor John Ralston Saul at the start of his introduction to each book.

The answer, based on the diverse, often highly creative takes on Glenn Gould, Big Bear, Lucy Maud Montgomery, and Marshall McLuhan, among others, was vigorously, and with notable appetite, in favour of Canada as a drama-charged landscape. But the series has struggled so far to engender the kinds of responses and conversations Saul must have hoped for when he wrote that “a whole new debate has been created around Canadian civilization and the shape of our continuous experiment.”

The intent of Extraordinary Canadians went well beyond acts of boosterism for Canadian writing, such as the rise of generous, often privately funded prizes—the Giller, the Charles Taylor, the Weston, the Griffin—or populist contests like CBC’s Canada Reads. That very determination to break new thematic ground, and to create fresh ways of looking at our “continuous experiment,” may have been the impediment. To buy into that proposition, readers must still believe there is enough shared ground and mission—enough of a shared experiment. They must believe there remains a centre, where a single conference in Kingston can kick-start a literature, and a single book about survival can enwrap a national project.

A broad, still unfolding process of diffusion may underlie the current publishing dilemma. Within a few years of the end of cultural nationalism, the energy behind it had been redirected toward a range of movements, or isms, with multiculturalism and post-colonialism erecting the biggest tents, each with its own agenda and constituency. The academy in particular, once a powerful force in CanLit, plunged down the theory rabbit hole, rooting too much scholarship in those few texts that confirm pre-existing critical discourses. It now talks mostly to itself, using an obscure dialect.

But readers, too, have been de-centred, by both tastes and technology. With the digital age has come the unmooring of the “where” of a book from the “what” of it. The attraction now is often pure content, and digital delivery systems ensure that ordering from an online publisher or seller, or subscribing to an e-magazine, can mean doing business with Saskatoon or San Francisco, Edmonton or Edinburgh. With such fluidity, allegiances will inevitably change.

Digital realities are certainly enforcing their own guidelines for publishing in the twenty-first century. Douglas & McIntyre sought bankruptcy protection for numerous reasons, including an expensive failed venture into digital publishing. But if there is a pattern to the disappointments of the past decade, it may be that mid-size, locally owned houses that try doing business like a multinational, only without the security that comes from publishing or distributing The Da Vinci Code and The Lord of the Rings (far easier sells, needless to say) in the Canadian market, are doomed. Running with that crowd, using a similar business model, may no longer work.

Innovating ways to publish and distribute books affordably, recruiting writers who can connect with those diffuse, de-centred readers, is an obvious tack for Canadian publishers. Back at Biblioasis, Dan Wells still issued eighteen new titles in 2012, many of which he hopes will be sold old-school: picked from bookstore shelves by interested readers. But he also retails e-versions from his website, and with a shop from which to hand-sell his (and other) titles is taking careful note of how little the spine of the book, identifying it as originating in Windsor or New York, matters anymore.

Truth be told, it never really did. It is worth remembering that supporting Canadian publishing has always been a minority cause. It has also long been an earnest, self-conscious one. Once, that minority had a great story to tell, a tale of passion and commitment and people pushing the boulder far higher up the hill than anyone had thought possible. Now, two decades and one paradigm shift onward, with so much industry talk centred on the nuts and bolts of a different, simpler kind of survival—that is, as any kind of entity at all—a galvanizing cultural narrative does not seem to be in the works.

But the current upheaval disguises something essential, and more hopeful. The problem is not that there are no good stories to tell about CanLit. Rather, there are too many. There is too much literary diversity, too much good writing and publishing being done in too many places by groups with, yes, different and competing tales of their long odds and uphill climbs. In the title of his stellar 2006 walkabout of the literary land, Noah Richler asked, This Is My Country, What’s Yours? He found (no surprise) that geography is destiny in our continent-wide nation, and no singular narrative can, or should, exist in such a setting. Canada may now be poised somewhere between a nation-state and a post-nation configuration with no easy name for it. Publishers, writers, booksellers, and readers should all proceed accordingly.

This appeared in the March 2013 issue.