If you’ve heard of Canadian writer Elizabeth Smart, it’s likely because of By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept, her thin but thunderous book of prose poetry first published, in England, in 1945. Based loosely on Smart’s obsessive pursuit of married British poet George Barker during her mid-twenties and the doomed chaos that ensued when they passionately collided, the book slowly gained an international cult following after its initial print run of just 2,000 and was eventually hailed as a masterpiece of rhapsodic fictionalized memoir. “Like Madame Bovary blasted by lightning,” was how novelist Angela Carter described it in the sixties. Gloomy British singer-songwriter Morrissey plucked lines from it in the eighties to co-opt as lyrics, including the novella’s final sentence, “Do you hear me where you sleep?” The BBC recently adapted it as a radio play, and on YouTube today, viewers can hear Smart’s lines tremulously intoned over shaky hand-held footage of the titular New York station.

Densely metaphorical, seemingly written at a fever pitch, and—as Smart herself freely admitted—only grudgingly plotted, the book has the richness and cadence of scripture. “There are no problems, no sorrows or errors: they join us in the urging song that everything sings,” she writes of angels and the transformative effects of love. “Just to lie savoring is enough life. Is enough.” Though Smart published a few other books later in life, and even her gardening notes have been immortalized in print, it is By Grand Central Station that anchors her literary reputation.

What far fewer people know about Elizabeth Smart—and what she declined to mention during the years I knew her in the 1980s—is that she spent much of her working life in London selling carpets, tiaras, and transistor radios as a witty fashion and advertising copywriter. She was reputed, at one point, to be the highest-paid commercial writer in England.

Smart’s romance with Barker didn’t go according to plan and, to support the four children she determinedly conceived out of wedlock and raised on her own, she suppressed her literary ambitions and channelled her poetic talent into slogans and captions. Her copywriting defied the trite, formulaic conventions of the 1950s and early ’60s. The cut of a cocktail dress was, in one of her ads, “as precise as a crocus.” In what almost seems a bittersweet parody of the ecstatic language in By Grand Central Station, Smart once wrote of terrycloth: “O the rapture of no-nonsense unruffleable toweling that doesn’t care two hoots how you abuse it.”

Her commercial-writing peers revered her efforts. In 1959, the writer Fay Weldon, then a fledgling copywriter, shared a workroom with Smart at Crawford’s Advertising Agency. “She would fall into the office from time to time,” Weldon wrote in her 2002 memoir, Auto Da Fay, “disheveled and beautiful and infinitely romantic, with her quivering eyes and distracted mouth, and teach me how to write fashion copy: all adjectives and no verbs.” Weldon told me that she and the other Crawford’s staffers regarded Smart, who by that point had started to drink heavily, with a “mixture of awe and fear. Fear in case she was too drunk and awe because what she did was so good.” But copywriting wasn’t what Smart felt she had been put on earth to do.

Elizabeth Smart was born into wealth in 1913, an initially obedient member of the Ottawa establishment. A funny schoolgirl hiding an eccentric intelligence. A debutante, gorgeous and blonde. A compulsive reader, diarist, and memorizer of Shakespeare sonnets. A scrapbooker who squirrelled away couture clippings from Vogue, like one that pronounced: “It was black lace this winter. It’s to be white lace from now on.” A privileged, restless young woman, she sailed across the Atlantic at least twenty-two times, haunting London bookshops. That was where, in 1937, she first came upon the poetry of George Barker, then the wunderkind protegé of T. S. Eliot. Upon reading Barker poems like “Daedalus” (“The moist palm of my hand like handled fear / Like fear cramping my hand”), she experienced a mental orgasm of sorts, later summing up her reaction as, “It is the complete juicy sound that runs bubbles over, that intoxicates til I can hardly follow . . . OO the a—a—a—!” She determined to marry him.

Over the next few years, she searched for Barker at parties, eventually tracking him to Japan, where he was teaching English. In 1940, she paid to bring him—and, inconveniently, his wife—to Big Sur, California, where Smart’s peregrination had led her. She soon found herself with child, alone, and the obscure author of the quasi memoir By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept, which the world would ignore for years. Though Smart’s relationship with Barker continued off and on for decades, he never divorced his wife. By 1947, Smart was in Ireland, now with four young children all fathered by Barker. She was estranged from her appalled society mother and largely cut off from the family funds. Virtually penniless, she fed her children boiled nettles.

Something had to be done. Smart hauled her herd back to England and, setting aside her unremunerative desire to pursue her hybrid of poetry and prose, began her career in magazines and advertising. “She kind of crawled her way up from the very bottom,” her son Christopher Barker, now seventy-six, told me over the phone from his Norfolk home. He describes his mother’s mindset at the time as “desperate.” Smart walked into the offices of slick London publications, he adds, and conned her way into writing jobs: “She said she could do something that she didn’t know she could do.” For House & Garden, she wrote of children, party-giving, and the publication’s wine guide: “If your wine-love is true-love, mad infatuation, or tentative attraction,” she ventured, “you’ll need House & Garden Wine Book. Sold out in a few weeks, but now being reprinted for your delectation.”

Presumably, advertising copy yielded bigger paycheques than magazine work, because she soon focused much of her energy there. In the early days, she dashed back and forth between London and the isolated country house where the children were tended by a witty, fractious pair of homosexual painters she’d befriended. She gave her brood little indication of what she did all week for money, or that Barker, who contributed nothing to their upkeep but appeared now and then, wasn’t her legal husband. “She was very secretive,” says Christopher. “She always talked about her masked heart, and this was certainly the case, not telling us really what had happened or what went on.”

Smart’s early advertising efforts, for companies such as Tootal Fabrics, seem constrained, as if she were trying to placate unimaginative clients. “If you sew,” she writes flatly and, I imagine, a bit miserably, “you deserve Tootal fabrics.” But she sneaks in bits of delectation here and there. She calls a little dress “as adaptable as a diplomat.” A swimsuit is “stitched to make the least of your figure.” Of a piece of outerwear, she deadpans: “Not just a coat—an accomplice to a busy life.”

As the 1950s went on and Smart entered her forties, she found her way into Soho’s bohemian scene, drinking and witticizing in private clubs with the likes of Dylan Thomas, Francis Bacon, and other “rogues and rascals,” as she called them. Lucian Freud painted her portrait, she once told me, starting at the top of her head and working downward, “but only got as far as the eyebrows.” As a rare member of the circle who was gainfully employed—though in an unspeakably pedestrian way—she often footed the bill. “Advertising was seen as a great shame and disgrace,” Weldon recalls, “because you had opted out for the sake of money.”

Determined to educate all four children in premium boarding schools, Smart worked and worked, freelancing for multiple ad agencies, penning a column called “Shop Hound” for British Vogue, and gradually committing to a more defiantly idiosyncratic voice. Of some “tough and indefatigable little chairs” from T. S. Donne & Sons, she quips that they “are unmoved by the most reckless sitters-down.” Like the poet she was at heart, she always read her work aloud to evaluate its quality. A contemporary remembered that Smart occasionally began her work day by sniffing Cow Gum glue, a layout paste, perhaps to jolt herself to write faster. When deadlines forced her to craft copy into the wee hours, she sometimes sent her eldest daughter, Georgina, out to Selfridge’s department store, where a friend who sold lamps in the basement could supply a couple of amphetamines. “I would get purple hearts for her,” Georgina, now seventy-eight, told me in her Kentish Town pied-à-terre, “so that she could stay up all night.”

Her children’s recollections differ on whether Smart took pride in churning out such clever copy, even if the work was only a financial means to an end. “I think she was proud of it, yes,” says Christopher. “I absolutely never heard her belittle it. I mean, she counted too much on it.”

Georgina is emphatic: “She just tossed it off without much effort. For her, if it didn’t cause her agony and torture and wrenching of soul, it wasn’t worth much. She did get drunk a lot and say, ‘I have a gift and I’m not pursuing it.’”

Though Smart remained largely unrecognized—the “real” writers she socialized with mainly knew her as Barker’s lover, and her sole published book was still an underground success at best—her reputation as a copywriter grew. In 1964, at fifty, she was asked to join the full-time staff of Queen, a brash fashion-and-society magazine (now known as Harper’s Bazaar). Writing nearly every word of its unsigned fashion copy, she pushed the limits, taking the sort of sui generis liberties with language that distinguish By Grand Central Station. For a feature on vacation clothes, she appeals to women who’ve grown lazy and disenchanted at the office: “Shirkers arise! Time for a paean of praise to fantasies and folies de grandeur before the workers lay you low.” She even asserted her literary authority, writing the magazine’s influential book-criticism column for two years.

Then, fate intervened when she was fifty-two: a power struggle of sorts pushed her out of Queen; By Grand Central Station was republished with fanfare; and she purchased a Suffolk cottage called “The Dell” that would, in time, become her permanent home, the place from which she attempted to reconstruct her identity as a real writer. She later referred to the purgatory she had occupied as a commercial writer as her “silent years.” They were, Christopher says, “her way of putting bread on the table for us. The price was, I think she felt, her dream of a place in the pantheon of lionized and acclaimed poets and authors.” Perhaps it wasn’t too late.

Ifirst met Elizabeth Smart in 1982, when she came into my staid, shallow world at the University of Alberta, in Edmonton, as the English department’s writer-in-residence. Though she’d had other, minor literary successes since her retreat to The Dell—a few volumes of poems, a jaded sequel of sorts to By Grand Central Station—I knew only that she was a sixty-eight-year-old Canadian who’d lived mostly in England and had written a book with a ballsy, indelible title. As a fiction-writing student, I was naturally immersed in words too, but I had mongrel tastes, being equally obsessed with Jane Austen and vintage fashion magazines featuring cover lines like “Pour on the Pretty Power.”

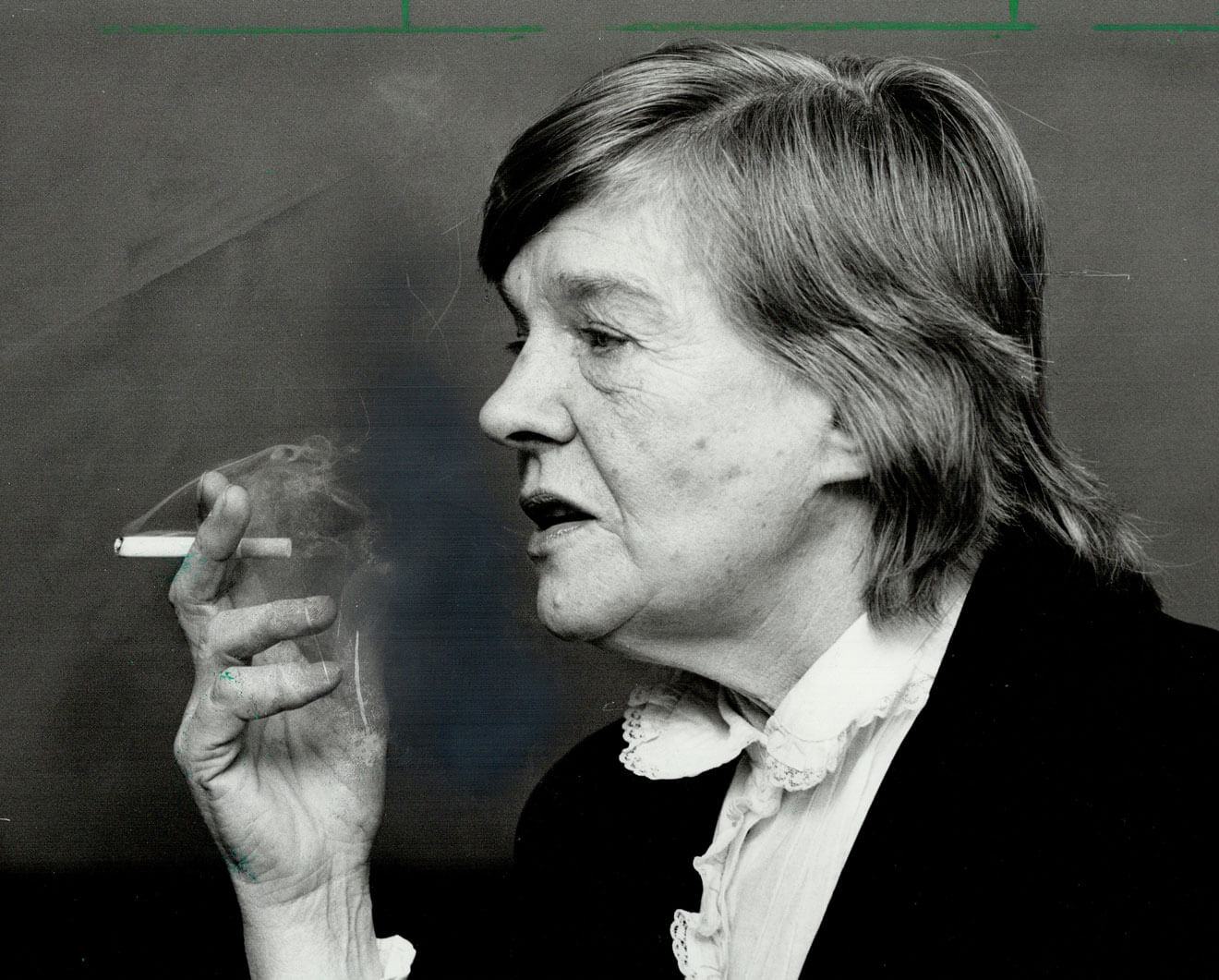

I was suitably reserved when I first walked into her office, Room 3-29, thinking her a writer with a purebred pedigree. She was seated behind a desk, and I was struck by her hair, a sort of wild, leonine bob—nothing like the clenched perms of the senior citizens I knew—and her smile, disarmingly dazzling. Pinned to the bulletin board behind her was an index card on which she’d printed “Make the Verb Work.” It was her sole addition to the barren space.

This exhortation, she explained, meant: seek out strong verbs that don’t need administrative support from adverbs. Pontificate, say, rather than hold forth pompously. (Not that she was even slightly pompous: she spoke as someone whose essential shyness warred with an irrepressible charisma.) Despite this reverence for verbs, she told me, her favourite word was an adjective, obstreperous. I had to look it up: “wild, turbulent, unmanageable, difficult, rebellious.”

I should have seen this as a warning: over the next four years, as Elizabeth welcomed me into her stormy, intoxicating world, she would both catalyze my ambition to be someone worthy of her friendship and painfully expose my inadequacies. A kindred spirit can turn out to be treacherous, both charming and overwhelming. It was years after her death in 1986 before I had any real understanding of the depths I’d been messing with.

Key revelations came when I read By Heart: Elizabeth Smart, A Life, an ambitious 1991 biography by Rosemary Sullivan, and first learned of Elizabeth’s conflicted forays into fashion and advertising. By then, I’d found my way into the commercial-writing world myself, and discovering this unexpected overlap in our fates intensified my sense of being haunted by my late mentor.

I soon made a hobby of excavating her past, and exhaustive Google Image queries eventually escalated into pilgrimages to London. By 2016, after I’d become the editor of the lifestyle section at the Wall Street Journal, it occurred to me that I could simply buy an old copy of Queen on eBay and pore over it in the tub. One issue soon became six, and for around $50 a pop, I studied Elizabethisms like “A Change for the Sweater,” the sort of punny headline I was cooking up for fashion stories myself.

I wanted more. In early 2018, I planned a two-day research trip to Library and Archives Canada, in Ottawa, where eighty-eight boxes of Elizabeth Smart materials are held, including scrapbooks of ads she penned, legions of her notebooks, and—I was startled to learn—three years of long-forgotten letters I wrote her, the first as a smitten and rather scarily unhinged nineteen-year-old.

That initial letter, sent in October 1982 soon after our first meeting, was housed in box thirty-four, alongside crisp correspondence from novelist Christopher Isherwood. Describing my reaction to reading By Grand Central Station, it begins: “I will write, I said, because I can’t speak—can’t speak the right words in the right order yet. Someday, I hope to. . . . Cut off my hands. Then I will speak.” Unamputated, I went on to detail my thoughts, as a theretofore sheltered suburban teen, on her book: “I felt like I was, comparatively, dead—had never really been alive . . . I wanted to strap you on my wrist to carry around like an extra heartbeat—an authentic one.” The letter ends, fatalistically: “You are becoming important [to me]. If you do not want this, take measures, take measures. Swat me away.”

Elizabeth was feeling bored and unappreciated by the English faculty in Edmonton. “To think!” she’d written in her journal, earlier that September, of the Edmontonians she’d met, “I was going to enrich their lives! And I find myself poverty-stricken . . . Needing them—if only they’d take pity on. Where can I find it, where is it hiding—the passion and the life?” It’s possible she saw passable passion in my nutso letter and, thinking it better than nothing, did not swat me away.

A friendship between us developed, its intensity fuelled by vodka, wordplay games, and what seemed, to my adolescent mind steeped in The Shining, evidence of a psychic bond: one night, in our respective beds on either side of the North Saskatchewan River, we both dreamt that we were sitting on straight-backed wooden chairs with paper bags on our heads. Elizabeth bought me books by highly stylized British writers, including Ronald Firbank, Saki, and Dame Ivy, intuiting that I was gay. Still, she gave me no indication of the years she’d spent writing fashion copy, though she must have known I would have eaten up such lore. Perhaps she felt it would mar her literary persona, newly restored. The paper-bag dream might have been telling.

She finished off her year in Edmonton and moved on to Toronto, where I stayed with her for a week. More vodka. More wordplay. An outing on the subway to see Woody Allen’s Zelig, about a nondescript person who takes on the qualities of strong personalities he encounters. I remember helping her walk home from parties as she weaved and slumped against hedgerows. I remember accusations that I’d been trying to read her secret notebooks.

Creatively blocked and unable to write anything of consequence, Elizabeth decided to return to her cottage in Suffolk, to her family and her real friends. Our correspondence began to dry up. In another mortifying letter of mine, this one circa 1984, I lash out at her, evidently feeling stranded in Edmonton and bored by anyone who wasn’t Elizabeth: “I miss you so much sometimes and other times you’re just sort of mythical and dim and like a medal—I lived through Elizabeth Smart. And now I’m supposed to be content with the common fellow and the common gal? Well, that’s just stupid. So fuck you for appearing and then disappearing and for being wonderful. Fuck you.”

“Oh, she would have loved that,” Georgina said fondly when I mentioned this old outburst of mine, “because she got nothing but ego stroking from nearly everybody.” In any case, Elizabeth must have responded encouragingly, because I went to visit her in her English cottage for two weeks the following summer. That’s when it became clear that I was too young and conventional to survive Elizabeth Smart at such proximity for long. On that trip, I met George Barker, who, by way of greeting, barked, “Are you a homosexual?” In a haze of sunshine, alcohol, and vintage Citroëns, I met Elizabeth’s brilliant adult children and her intimidating friends (“Oh, you’re the Canadian”). If Elizabeth had felt rather insecure among her “real” writer friends in ’50s Soho, I felt intensely so in her circle: uncredentialed, dull, overwhelmed, jealous. I finally fled after one too many drinking sessions with old, extremely witty people who had a rich shared history and zero interest in me. I ran out at 1 a.m. without even saying goodbye—first to a hotel, then to Edmonton.

Elizabeth and I didn’t speak for months. Later, in a letter, I blamed my exit on a “distrust of ripeness. . . . You must understand that this is why I ran away a year ago to Canada. I had forgotten, in two weeks, how stilted and pallid, how harsh and prim and relentless it was. But it was Home.”

In box thirty-four, I found one more letter I’d sent Elizabeth some months before she died. It describes a phone call, a final attempt to reconnect and rekindle our friendship: “I am sorry to have telephoned you when I was so blue and stupid. Not even as an opportunity to watch something die,” I added, in reference to our fraying bond, was the call “worth our whiles.”

As I sat reading my own words in the Ottawa archives, wearing the requisite white cotton gloves, I realized that that something hadn’t died at all: her possession of me had only grown more entrenched over the years. Like her, I am someone who despairs of boring sentences, who disdains hackery and compromise, though we both made considerable compromises. Reading her copy, I noticed that she characterizes certain pieces of clothing as “extroverts,” anthropomorphizes sunglasses or plums or Venice, and, unconsciously or not, strings words together because they sound alike. All things I do too. Like her, possibly because of her, I write with my ear.

She does it all better, of course. In the era of Instagram ads, it is exceedingly rare to find copy that has anything resembling the curious lyricism and metaphorical resonance that Elizabeth achieved—or, as Georgina put it, “tossed off”—before she aged out of the fashion game (despite getting more than one career-extending facelift, according to her daughter). “When the towel got emancipated,” she wrote, for Queen, in 1966, “a whole series of compatible holiday clothes emerged, in all shapes and moods. And they all mop up the sea. They all suck up the suntan oil. They need no care or attention. They loll and wallow with you with an unstrict chic, careless as in their old bathtime days. And they look even better when they’re battered.”

This is craft that blurs with art. Elizabeth’s “real” writing has arguably eclipsed George Barker’s (By Grand Central Station is still in print; most of his poems are not), but the hard work of her so-called silent years speaks compellingly too. Even when the going got tedious, Elizabeth did not give in to hackery. When I’m tempted to do so myself, I feel her rueful disapproval through the decades. Never compromise, I hear her say. And I redouble my efforts to make the verb work, still trying to be someone worthy of her notice.