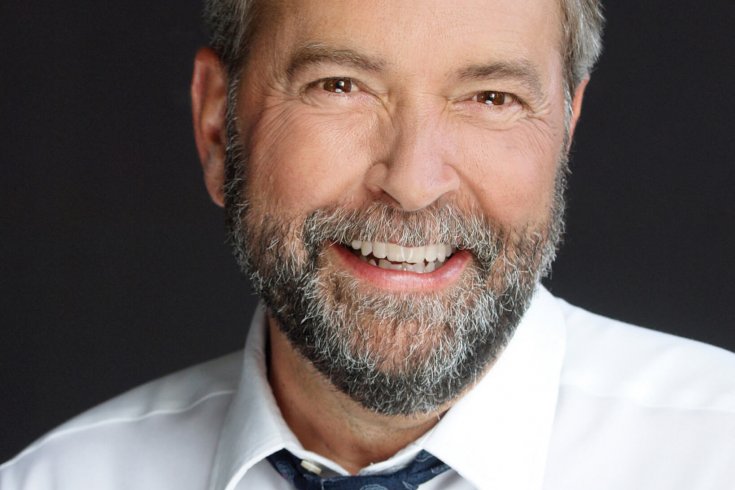

It is a curiously Canadian scandal: a social democrat outed as a closet free-market Tory. Last week, decade-and-a-half-old footage emerged of Thomas Mulcair, the leader of the federal NDP, praising—of all people—Baroness Margaret Thatcher. “A government should never pretend it can replace the private market. It does not work,” he said, in French, at a 2001 National Assembly commission, when he was still a Quebec Liberal. “It didn’t work in England. Up until Thatcher’s time, that’s what they tried. The government stuck its nose everywhere. A wind of liberty and of liberalism in the markets has been blowing in England and, instead of being one of Europe’s worst-performing countries, England has become one of the best-performing ones.”

By now, it is a truism among progressives that Mulcair is a traitor to the cause, and his kind words for Thatcher, however long ago, served to underscore the point. The laundry list is long: his purging of candidates who have been even mildly critical of Israel; his refusal to consider raising taxes on the wealthy; his support for tar-sands expansion; his war with party stalwart Libby Davies; his approval of the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement with the European Union; his waffling on the Energy East pipeline. He threw Linda McQuaig, a star candidate in Toronto, under the bus, thanks to her support for higher taxes on the rich and her eminently accurate observation that “a lot of the oil-sands oil may have to stay in the ground” if Canada is to meet its emission-reduction targets. He has committed the NDP to a balanced budget—even as many experts believe the economy is in recession—and he pulled out of the women’s issues debate after Stephen Harper declined to participate.

If the polls are correct, on October 19, Canada could see something unprecedented: a federal NDP government. But would that be a victory for the Canadian left? It is easy to dismiss criticism of Mulcair as mere ideological purity—diehard Reform partisans had similar complaints about Harper—but that is only half-right. Instead, it is possible that the NDP is more effective as an angel on the Liberal Party’s shoulder than as a serious contender for power. The most progressive federal budget in recent history came ten years ago, in 2005, when Jack Layton strong-armed Paul Martin for $4.6 billion in additional social spending and foreign aid, and promised, in exchange, to keep the fragile Liberal minority afloat. At the time, this came to be known as the “NDP budget,” thanks to its generous provisions for housing, tuition reduction, and public transit. A few months later, of course, the NDP joined the Conservatives and Bloc Québécois to topple the Liberals—ushering in the next nine years of Harper rule.

Would an NDP government pass a budget like that? Mulcair is a consummate politician, one who believes nothing and anything; the fact that, after leaving the Liberals, he was seriously courted by both the Tories and the NDP tells you everything you need to know. It is difficult to believe he would propose something quite so audacious as Layton’s bargain, given his commitment to balancing the books. “It’s between jobs and growth or austerity and cuts—and Tom Mulcair just made the wrong choice,” Justin Trudeau said not long ago. Such is the state of our parliamentary left; the Liberals are more eager to use the a-word than the NDP.

Accepting a reduced role does not come naturally to political animals, and one sympathizes with those in the NDP who believe that the party should do what it must to win, at which point it will legislate in accordance with its lineage. But every political hack knows the opposite is the case—“campaign from the left, govern from the right,” that old saw, is no less true for being a cliché. In the provinces that have recently elected NDP governments—Manitoba, Nova Scotia—the party has not acted altogether differently from the Liberals. (It’s still too early to tell in Alberta, but take an educated guess.) Crucially, it has also faced no pressure from its left flank. After all, it does not have one.

It was not always thus. Layton, for all his faults, came up through civic activism and municipal politics. Although he started the NDP on its current path, his heart was in the right place, and he believed in the party’s roots. Under Layton and previous leaders, supporters could trust that, regardless of quibbles here and there—such as Layton’s support for reactionary tough-on-crime policies like mandatory minimum sentencing—the party’s MPs and activists were in the game for the best reasons. If they sought power for its own sake, wouldn’t they just join the Liberals? But should the NDP replace the Grits as Canada’s party of the centre-left, that trust will be gone. The NDP is often referred to as Canada’s conscience, and, however trite, this is a neat formulation of its role. Let the Liberals be the Liberals; let the NDP continue toiling in the thankless, essential winter of opposition.

Still, it is important not to overstate the case. For progressives, an NDP government would undoubtedly be better than another Conservative majority. If the NDP can execute two key centrepieces of its platform—pass universal childcare and repeal Bill C-51—that alone justifies a vote for the party. But those would be pyrrhic victories. The Liberals were poised to implement childcare in 2005, before Layton cynically opted to sink Martin. And repealing a draconian anti-terror law, one panned by legal experts across the political spectrum as a gross overreach, hardly represents progress. It is just a step back from the brink.

Mulcair is not Margaret Thatcher, but he might be Tony Blair—and that is the more instructive comparison. Although Blair resurrected Labour as a serious electoral force, he is now despised in the UK as a betrayer of the party’s founding ideals. “Power without principle is barren,” he famously said, “but principle without power is futile.” In his wake, centre-left parties throughout the West are coming to understand that emphasizing the latter at the expense of the former leads to ideological bankruptcy. The emergence of Bernie Sanders as a credible threat to Hillary Clinton, and of Jeremy Corbyn as a viable candidate for the Labour leadership, is proof—all the more surprising given that these men, aging socialists both, are electrifying their parties’ young bases as few others have.

Canada appears headed in the opposite direction. We expect our parties to represent the true diversity of political belief—which is why we have a multi-party system in the first place. But in the Mulcair era, there is no longer a legitimate parliamentary option for Canadian leftists. On election day, Mulcair very well may lead his party to victory. The question is whether that party will still, at heart, be the NDP.