On the morning of August 8, 2015, just before 9 a.m., a grey-haired man in a suit walked out of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York. He carried a small tray of laminated plastic numbers, one through nine, along with the fraction one half. The small crowd waiting outside the doors—we who had travelled from Calgary and Hamilton and Boston and San Diego to visit the Hall—regarded him expectantly. We wanted in. “Soon,” the man said, and disappeared around the corner.

“He’s going to update the standings,” said my brother-in-law, Owen.

The standings. They were neatly displayed in a case out front of the Hall, facing the town’s quiet Main Street. For Owen and me, the American League Eastern Division column was undergoing a long-awaited transformation. Our beloved Toronto Blue Jays were on a tear, six games into an eleven-game win streak. We had arrived at the fabled birthplace of baseball smack-dab in the middle of this ascension, stumbling around in happy delirium as the Jays closed in on the faltering New York Yankees. The Jays were just four and a half games out. By the streak’s end, they’d take first place.

The timing of our visit was plain luck. Or handiwork of the baseball gods, if you believe in that sort of thing. We’d planned the trip back in March. It would be a whirlwind weekend: Leave Hamilton Friday and drive to Cooperstown, spend Saturday at the Hall, and on Sunday see the Jays at Yankee Stadium. It would be my first visit to both Cooperstown and New York City.

We’d gone through countless summers of baseball disappointment, and couldn’t quite bring ourselves to expect anything different. If the pattern held, this would be another nothing August. At best, there would be a shot at the wild card, baseball’s back door into its playoffs. The Hall would give us the comforting balm of nostalgia. Look, Roberto Alomar’s jersey. Paul Molitor’s cleats. Joe Carter’s bat!

But the names of 1992 and 1993 were not on our lips that weekend. We were learning to speak a new language. Price. Tulowitzki. Revere. They were the winnings of late-July trades, acquisitions too good to be true. We said the unfamiliar names over and over, like a mantra, never tiring of them.

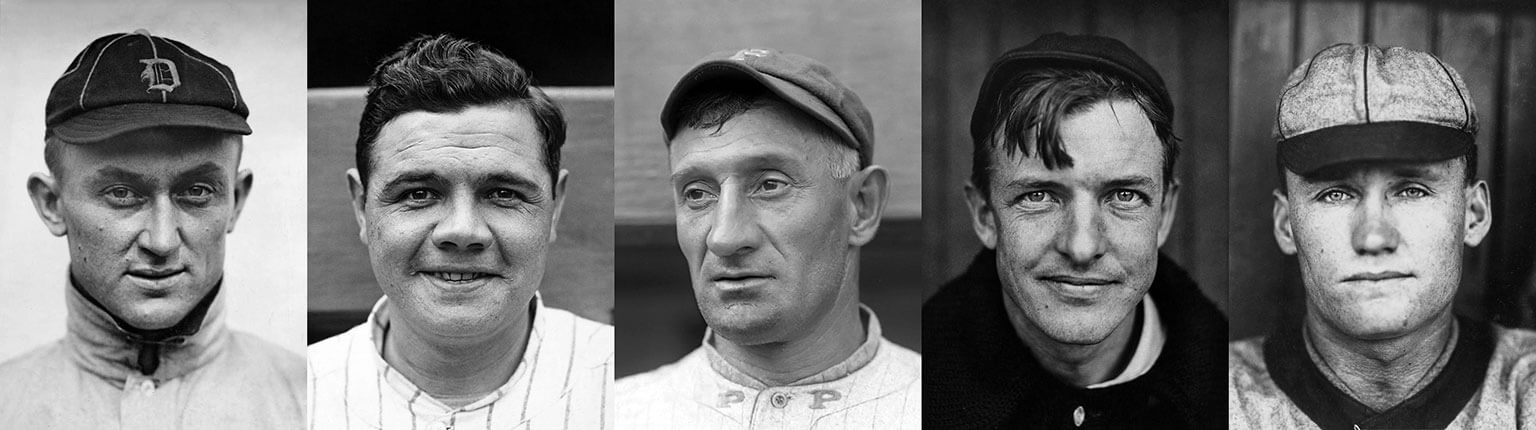

When the Hall opened, we went inside and were whisked away to the great baseball moments of the past. Ty Cobb slid malevolently into third. Babe Ruth called his shot, or didn’t. Jackie Robinson sped home. We revelled in it all, but nothing—no, not even Joe Carter’s home run—laid claim on us like the baseball drama of the present.

We were utterly rapt. Friday night, before the first Jays-Yankees game of that weekend, we dropped by Doubleday Field, the town’s bandbox stadium. Two Little League teams had at it as the lowering sun drenched the field in crisp golden light. We breathed it all in, but couldn’t stay long. First pitch was ten minutes away.

We found a diner with TVs and settled in. In the second inning, Yankees first baseman Mark Teixeira lifted a deep fly off Jays knuckleballer R. A. Dickey. As left fielder Ben Revere leapt up for the catch, a fan reached over the outfield wall and touched the baseball. Or did he? Either way, the ball glanced off Revere’s glove and stayed in the park. The play went to video review. Over beer and cheeseburgers, we argued with the New York fan at the next table. “No home run,” we said. “Woulda gone out if that guy hadn’t touched it,” he countered. MLB’s review crew sided with him.

We still say it was no home run. But sure, let them have their lousy dinger. It would be the only run the Yankees would score all weekend. Later that game, in another pub, we cheered as Jose Bautista (who else?!) launched a tenth-inning homer—a real one, well over the fence into the Jays bullpen—to break a 1–1 tie and win the game. The Jays had now won six in a row.

The dream kept on. We never awoke. On Saturday, after going through the Hall, we stopped at a spot called Hey, Getcha Hot Dog. There, we watched the Jays’ new lefty ace David Price work his first few innings before we hit the road for New Jersey, en route to New York City. Price was masterful that day, pitching seven shutout innings, but we briefly lost the radio broadcast on the road. When we got a clear AM signal again, the words “Justin Smoak grand slam” rang through. Jays won 6–0. Seven in a row.

The next day on the Brooklyn Bridge, a tour guide in a Yankees hat spotted our blue jerseys and loudly berated us. “Blue Jays fans?! Get outta town. Get outta heah!” We laughed and practically floated to the subway, Bronx-bound and euphoric. With the Yankees bats gone silent, we felt like the kings of New York.

That afternoon, in the Yankees’ opulent, soulless new stadium, Jays starter Marco Estrada picked up where Dickey and Price had left off. He mowed down the Yankees lineup. There was a moment in the seventh that had me worried. I’d come back from getting a hot dog, and there was Jays designated hitter Chris Colabello, who came out of nowhere to hit .321 this season, writhing on the ground next to home plate. I’d missed the pitch and feared the worst. I caught the eye of a nearby Yankees fan and asked if the pitch hit Colabello’s head. He shook his head no. “Hand,” he said. I was awash in relief.

Bautista and the godlike Josh Donaldson both homered that afternoon, the game’s lone runs. After the former’s shot, a Yankees fan disgustedly threw the ball back onto the field, carrying on a long tradition. What happened next was not part of the tradition: the ball struck the left fielder, Brett Gardner, in the back of the head. For New York, it was that kind of weekend. The Jays completed the sweep. Eight in a row.

As we left our seats, the legendary bravado of New York fans had evaporated completely. Only Frank Sinatra was going on like the Yankees still had any chance, crooning over the PA system, “It’s up to you, New York, New Yooooooooooork.” The local faithful were subdued, resigned, crushed. Part of me wished we could take their misery, stick it in a bottle, and put it in the Hall for future generations to open and enjoy. But we felt for the New Yorkers, too. They already knew, we all knew, that this year belonged to us.