The shocking announcement came at the eleventh hour. Just two days before the US National Association of Black Journalists convention—the annual multi-day conference that brings together thousands of Black journalists and other media workers for panels, workshops, award ceremonies, and a job fair—organizers sent an email to the NABJ’s general membership announcing that former president Donald Trump would take part in a moderated conversation with journalists. They said Trump’s appearance was part of a long tradition of hosting former presidents and candidates to speak at the convention, including George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Bill Clinton. They added that they’d extended a similar invitation to vice-president Kamala Harris, who, it was later revealed, was not able to attend in person but would provide a virtual address at a later date.

I was heading to the convention with an inaugural delegation of fellows from the Mary Ann Shadd Cary Fellowship for Black Journalists, and initially, I had no interest in going to Trump’s event. I had set up interviews with prospective employers during his scheduled appearance—some of the best news outlets and journalism schools in North America—and those seemed like a better use of my time than going to see an overtly racist, sexist, xenophobic, and autocratic former leader. After all, the NABJ convention was a time for rejuvenating, connecting, and bolstering journalists.

Last year was my first time attending, at the suggestion of Deborah Barfield Berry, then a Nieman Fellow at Harvard University, whom I’d interviewed for my research on objectivity, race and journalism. (The research and subsequent Nieman fellowship came after an award-winning 2020 article on the subject in this magazine.) If you want to talk to generations of Black journalists about objectivity, come to the NABJ convention, I remember her saying. What I found was much more than potential research subjects. As an independent journalist who admittedly had one foot in, one foot out of our embattled industry, I felt like I belonged in journalism once again. This year, I was looking forward to another opportunity to have my commitment to the industry renewed in fellowship and fun.

The morning of Trump’s appearance, I had a change of heart. I remembered that, at its root, journalism is about witnessing and documenting, accurately, unflinchingly, the first draft of history. And here I had a chance to see the disgraced former president and current Republican candidate with my own eyes, hear him with my own ears, unmediated by format, timing, and editing, after nearly a decade of reading about and sometimes covering him during my years as a daily current affairs radio producer.

I also remembered one of the core principles of objectivity—not as a personal quality but as a discipline of verification, a method of working against one’s biases by acknowledging them and challenging them in one’s coverage. It was precisely because I didn’t wish to see Trump that I thought it was important to show up. I admit, I was also curious: organizers said they wanted an opportunity to talk to Trump about pressing issues in the Black community. Would they ask about reparations, police violence, redlining and the crisis of Black home ownership, wealth disparity, or Black maternal health, for example? Would they ask Trump about the US’s continued political and military support for Israel’s war on Gaza, which has killed over 40,000 Palestinians, including more than 100 journalists?

And so, two days later, at a hotel in downtown Chicago, I, along with hundreds of other journalists, lined up for two hours, undergoing metal detector checks and inspection by security and walking past what seemed like Secret Service officers. Instructions were strict: there would be no water bottles allowed in, no trips to the bathroom once admitted. Trump was scheduled to speak at noon on Wednesday, July 31, but it was over an hour later when the session finally began.

The three moderators emerged on stage. The already tired expression on the face of ABC’s Rachel Scott was a window into what was likely a tumultuous time backstage. Her first question to Trump—who stepped out to a smattering of applause and paltry cheers from a small but loud group of supporters who sat to my right—was perhaps the best one of the whole conversation. She listed a litany of racist and xenophobic comments he’d made—which included telling four racialized congresswomen to go back to where they came from, questioning of the birthplaces of former president Barack Obama and former governor of South Carolina Nikki Haley, attacking Black journalists, and hosting a white supremacist for dinner at his Mar-a-Lago resort. She ended by asking, “Why should Black voters trust you after you have used language like that?”

What happened next has been much reported on. Trump reprimanded her, calling it a “nasty question” and ABC a “fake news network.” This opening spat would set the tone for the rest of the session, which lasted just over thirty-five minutes and in which Trump repeatedly made false claims about an “invasion” of “illegal aliens” into the US from mental institutions and prisons abroad and mispronounced Kamala Harris’s name while expressing confusion about her racial identity. “I didn’t know she was Black until a number of years ago when she happened to turn Black, and now she wants to be known as Black,” he said. “So I don’t know. Is she Indian or is she Black?”

A number of attempts at heckling Trump were met with vehement shushing, attendees seemingly not wanting the event to devolve any further. At one point, according to another member of the Canadian delegation who sat in another part of the ballroom, someone yelled out, “Sir, have you no shame?” only to be loudly shushed by those nearby. Another attendee sat with their back to the stage, a form of quiet protest that still bore witness. While the anger in the room was palpable, hardly anyone booed. We all knew that the managers and executives of every major news organization were watching or present and that open expressions of dissent might be frowned upon—or even considered fireable offences.

In the end, Trump’s appearance was more of a grim spectacle than a substantive conversation: his constant deflections, meanderings and falsehoods overpowered the discussion. For the rest of the convention, attendees repeatedly questioned the point of inviting him. At one panel, Nikole Hannah-Jones, the Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist and creator of the 1619 Project, who is also the founder of the Center for Journalism and Democracy at Howard University, criticized the false sense of balance that’s prevalent in political reporting. “I did not believe that NABJ…that came out of the traditions of the Black press, should give a platform to someone who does not believe in democracy…. I’m not saying we don’t cover him,” she added, “but I don’t know that we lend our platform to that.” She also questioned the highly curated format, which prevented other journalists in the room from getting a chance to ask questions.

She has a point. We were held hostage by a false sense of objectivity, forced to watch a former president who has shown nothing but contempt for our profession—a man who has even endangered journalists by singling them out and attempting to delegitimize coverage that critiques him—run roughshod over the moderators. A fellow Muslim journalist and I jokingly wondered what we were even doing in the room given Trump’s history of Islamophobia and so-called Muslim ban in 2016. Many journalists were skittish in discussing their feelings about Trump’s appearance publicly, not wanting to jeopardize their jobs or their ability to cover him.

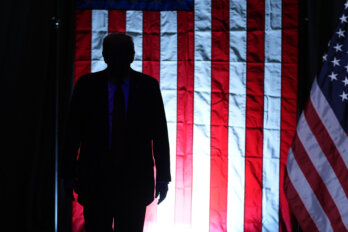

When I got home to Toronto, I rewatched a recording of the event on TV, wanting to reabsorb what I’d seen in person. When the camera cut to a close-up of Trump, he was framed squarely against a backdrop of three American flags, the red and white stripes almost blending in with his white shirt and red tie. And it was then that I saw it perhaps most clearly: Trump’s derision and contempt for the free press and the Black women who represented it onstage that day were simply a reflection of a country that has long punished Black people for demanding equality, freedom and a democracy that includes them. ABC’s Scott, who ended up being Trump’s strongest challenger on that stage, is now facing harassment for daring to exercise the democratic right to hold power to account: NPR journalist Eric Deegan tweeted that, at a membership meeting a few days after the convention, NABJ’s executive director told attendees that Scott has faced death threats for her unflinching questions. As the debate continues about whether it was worth inviting Trump to a convention for Black journalists, that alone seems like too high a price.

Many of us sensed that Trump’s appearance could not end in anything but unsatisfying, chaotic, purposeless danger, but we still saw it through for ourselves. As Maya Angelou famously wrote, “Believe people when they tell you who they are. They know themselves better than you.” What was the point of inviting him into a space of safety, community, and care for Black journalists? What was gained by trotting him out to repeat his abhorrent shtick in front of an audience who ultimately had no recourse to hold him accountable? If we believe that journalism is not mere stenography but a discipline that should be in service of upholding a multiracial democracy, why was someone who has shown contempt for both racial plurality and democracy given the biggest platform at a convention for Black journalists? What did it mean that even at a convention for Black journalists, in a room full of Black journalists, there was pressure to remain “objective” toward a man who was openly spewing racism?

In the end, it was the ultimate irony that the NABJ chose to give such a major platform to Trump, a famous disseminator of falsehoods, at a convention whose theme was “journalism over disinformation.” The convention was an important reminder of the activist roots of the Black press, in the spirit of anti-lynching activist and journalist Ida B. Wells. She would have laughed at the idea that we should ignore our own humanity in the name of detachment and objectivity.