In the early hours of August 19, 1942, Roy Hawkins, a twenty-one-year-old sergeant from Fort McMurray, Alberta, walked purposefully through the grey passageways of a troop transport as it steamed toward the fortified town of Dieppe (population 16,000), on France’s northern coast. He was looking for another soldier. Built as a ferry to travel from Harwich to Hook of Holland, HMS Princess Beatrix was one of 237 vessels carrying some 5,000 Canadian, 1,000 British, and fifty American troops to beaches code named Yellow, Blue, Red, White, Green, and Orange. On the mess decks, soldiers did what soldiers do before battle: played cards, sharpened bayonets, wrote letters home, prayed. And, of course, worried: a private nicknamed Red complained to Sergeant Jack Nissenthall, the man Hawkins was trying to find, that their new Sten guns might seize up in the heat of battle, because the rivets hadn’t been filed down properly. When Hawkins caught up with Nissenthall, he told him that he, Hawkins, would be commanding the ten-man unit assigned to help Nissenthall steal the secrets of Freya, a German radar station near Pourville, just east of Dieppe. Neither man mentioned it, but both knew that an order unique in the annals of the Canadian military now rested on Hawkins’ shoulders. Nissenthall was not a Canadian soldier. He was, in fact, a twenty-two-year-old British Royal Air Force officer with top secret knowledge of the radar system that had stymied the Germans during the London Blitz. Hawkins’ job was to get Nissenthall, known to the Canadians of the South Saskatchewan Regiment as Spook, out of France. If for any reason Hawkins could not do so, he was instructed to kill him.

When she learned of the plan to attack Dieppe a few months earlier, Winston Churchill’s wife, Clementine, who had been raised in the French town (where Oscar Wilde sought refuge after his release from prison), reminded the British prime minister that it was flanked by honeycombed cliffs from which the Germans could easily repel the attackers. But, for geopolitical reasons, Churchill supported Operation Rutter (named for a type of mounted mercenary soldier), which was originally to take place the first week of July. No one—not Lord Louis Mountbatten, Chief of Combined Operations, who lobbied for and directed the operation; not the British Admiralty, which was responsible for transporting the attacking force to and from France; and not the Royal Air Force, which was to provide air cover—no one believed Rutter constituted the second front many people in the United Kingdom, the United States, and Canada were calling for. A second front would have required an invasion, the taking and holding of beaches, and then an advance through France and into the Reich, as would occur two years later, beginning with D-Day. Rather, Rutter was a “reconnaissance in force,” the plan being to seize the headlands to the east (Pourville) and west (Puys), and finally Dieppe itself, testing the German defences—and then to get out before the second tide. It was thus much less than Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, whose armies were retreating toward Stalingrad, demanded. But after the humiliating fall of Tobruk in June, Churchill and President Franklin Roosevelt decided, despite their promises to Stalin, to invade North Africa instead of France. Operation Rutter served as a way to demonstrate that the Western Allies remained committed to Europe, in the only coin Stalin recognized: blood.

Mindful of Gallipoli, where more than 44,000 Allied troops died between April 1915 and January 1916, the planners of Rutter called for massive air and sea bombardments to destroy the German fortifications. But concerns about having his bombers caught out in daylight, as well as his commitment to the strategic bombing campaign over Germany, led Sir Arthur Harris of Bomber Command to turn down the request for heavy bombers, although he did offer up some lighter ones. More forthcoming was Fighter Command’s Air Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory, who saw Rutter as a chance to entice the Luftwaffe, which was savaging Harris’s bombers nightly, into a decisive battle. Leigh-Mallory assigned more than seventy squadrons, including nine from the Royal Canadian Air Force, to provide air cover and mount cannon attacks on Dieppe’s main beaches before the landings. The operation’s planners also requested fifteen-inch naval guns to blast away at the German defences, but the Admiralty, too, remembered Gallipoli, where it had lost several capital ships, and it refused to assign anything larger than destroyers with four-inch guns.

Decades later, Brigadier General Denis Whitaker, at the time a captain training with the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry on the Isle of Wight off the coast of Britain, would dispute Defence Minister James Ralston’s claim that after more than two years of garrison duty the Canadian troops were anxious to go into action. However, there was no denying the readiness of the minister; his delegate in England, General Andrew McNaughton; and Lieutenant General Harry Crerar, who commanded the corps to which the division belonged. In February 1942, Crerar complained that training “provides neither pride nor pleasure to the officers and other ranks,” and he joined Ralston and McNaughton in requesting that the British include Canadian troops on raids. Less enthusiastic was Prime Minister Mackenzie King, who had earlier witnessed the folly when Crerar assured him that there was no risk in sending 2,000 men to bolster the British garrison at Hong Kong and the entire garrison was subsequently killed or captured in December 1941. By mid-May, King was referring to Rutter as “Canada’s Gethsemane.” Major General John Hamilton “Ham” Roberts, commander of the Second Canadian Infantry Division, shared the prime minister’s misgivings, but nevertheless accepted command of the mission and oversaw the loading of his men and matériel into several hundred ships at Yarmouth Roads, UK, in early July.

But Operation Rutter was not meant to be. On July 7, after days of adverse weather—and, worse, a German bombing raid on the ships, which gave the Luftwaffe photographic evidence that Hitler had been right in predicting that the Western Allies would cross the English Channel to relieve the pressure on the Russians—the operation was scrubbed.

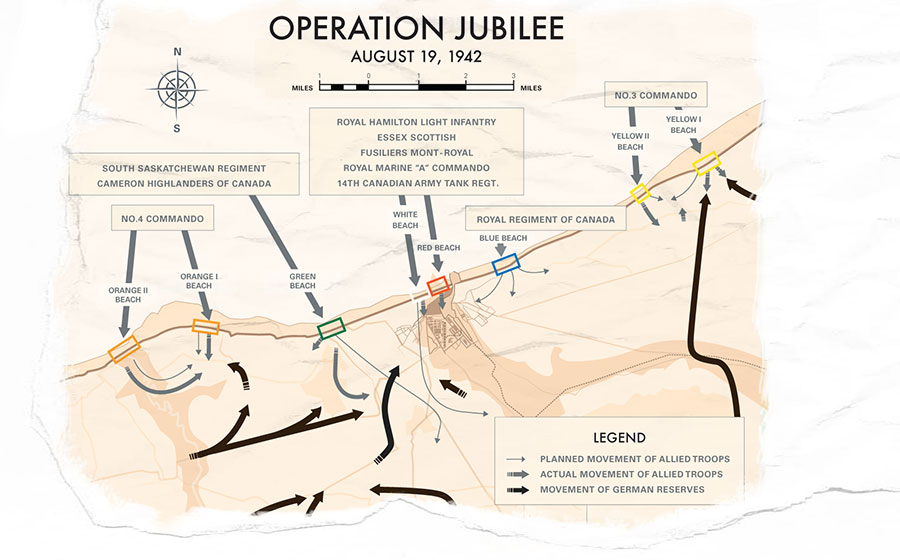

The decision to remount the raid, renamed Operation Jubilee, was one of the war’s strangest. Mountbatten had written authority to mount the attack on Saint-Nazaire, which destroyed the largest dry dock in France in March. He had written authority for Rutter. However, no written record has ever been found giving him the authority for Jubilee, although years later he claimed that Churchill had granted him a verbal go-ahead. In any case, Combined Operations swung into action, and in the days and weeks leading up to August 19 its members met with the RAF, the Royal Navy, ordinance officials—and, of course, Major General Roberts—to map out the new operation. Jubilee would differ from Rutter in three respects: the airborne units that were to secure the raid’s flanks would be replaced with commandos; the US Air Force, not part of the original plan, would bomb a single German airfield at Abbeville–Drucat; and the time ashore would be reduced from two tides to one, without scaling back the raid’s objectives on the ground.

Significantly, Mountbatten put his protege Captain John Hughes-Hallett in command of the naval force, replacing Rear Admiral Harold T. Baillie-Grohman, who had written a letter on July 9, co-signed by Roberts, calling into question Rutter’s feasibility. At a meeting with Mountbatten and McNaughton two days later, Roberts, whose training as an artillerist told him that Jubilee lacked the required punch, said that despite his reservations he would proceed if instructed to do so. He left the meeting with a battle plan that called for attacks by commandos on the far left (Yellow) and right (Orange), followed by two battalion assaults on the beaches east of Dieppe (Blue), two on the beaches west of Dieppe (Green), and finally a frontal attack by two more (Red and White), including tanks, on the stony beaches of Dieppe itself. The direct attack on Dieppe was to take place just after dawn—and after those to the east and west—which makes it difficult to see how Roberts’ men could have achieved the surprise everyone agreed was necessary for the raid to succeed.

On August 19, at 0435 hours, a German tug reported suspicious ships to the Dieppe harbourmaster, but forty minutes passed before gunners above Green Beach received the order “Open barrage fire.” By then, under the cover of strafing RAF Spitfires, the Saskatchewans had advanced against desultory machine gun fire and, after clipping through the barbed wire, established a headquarters in a garage 100 metres beyond the seawall. With his eyes fixed on Freya’s oscillating radar antenna, Hawkins led his party through another gap in the wire into Pourville, where the narrow streets made machine gun fire more dangerous. They advanced in carefully timed sprints, each ending with Nissenthall and his Canadian minders hugging the white stone walls. The rattle of the machine guns awakened the dieppois, who were horrified to see their quiet streets turned into a battlefield. “Why have you come? ” some asked. “They [the Germans] have been waiting for you for three weeks.” There is no evidence, however, that the Germans had any foreknowledge of the attack, although it must have seemed so to the men of the Toronto-based Royal Regiment of Canada, who were slaughtered as they landed at Blue Beach, fourteen kilometres to the east, at 0506 hours.

Shannon Jager

Shannon JagerEven though they landed sixteen minutes late, and thus in the strengthening light, the Royals might have avoided massive losses. But the muffled sounds of a battle at sea, between part of the invasion force and a small German coastal convoy, prompted German commanding officer Hauptmann Richard Schnösenberg to call an unscheduled “morning alarm exercise,” which meant that at 0506 hours, just as the fog lifted, he spotted the White Ensign fluttering from the sterns of dozens of landing craft. “Est ist das English! “ he shouted. “Fiere! ” A hail of mortar and machine gun fire killed some of the Royals as they leaped onto the beach, and others while they still crouched in their landing craft. Jumping over a row of dead bodies put Sergeant Major Norman MacIver in the way of a bullet that penetrated his steel helmet but did not stop him. What did was the sight of a wounded soldier; setting aside his training (“Moving is safer than stopping”), he paused to pick the man up and carried him through the kill zone, past heaps of broken and bleeding bodies to the concrete seawall, before passing out. Unfortunately, the wall afforded little protection. Nearby, a mortar explosion knocked out a stretcher- bearer, and tore the head off a soldier whose body fell on the unconscious medic.

The second and third waves of Royals, including elements of the Montreal-based Black Watch of Canada, bled and died under fire so “brutal and terrible,” reported CBC journalist Ross Munro, that it shocked him “almost to insensibility.” Amid the carnage, Lieutenant Colonel Douglas Catto, the Royals’ commander, lay prone on the seawall, clipping away at the tangled barbed wire. Once through, he led twenty men up a hill, where they destroyed six machine gun units. This provided some relief for the men on the beach, but the battalion’s mission—to secure the attack’s right flank—was by now unattainable. At 0740 hours, when Roberts received the message “Doug landed three companies intact at Blue Beach…all going well,” the attack had already collapsed, and Catto’s small force was cut off from the beach, where German fire steadily reduced the broken remnants of his battalion.

At 0505 hours, a single rocket rose above Pourville, and the cliffs on either side of the village erupted in orange flame. The whistle of one shell coming close gave Nissenthall just enough time to hit the dirt and open his mouth so the pressure wave that followed the explosion would not puncture his eardrums. Red, the Saskatchewans’ fretful private, was not so fortunate; a small piece of steel from an exploding shell drove through one of his eyes and into his brain, ensuring that he would never get to use his new Sten gun. In the half-light before dawn, Hawkins saw a Frenchman transfixed by the sight of the German artillery cutting down the Saskatchewans’ second wave. Moments later, as the bridge that bisects Pourville came into view, to his dismay he realized he had been put down on the wrong side of the River Scie. To reach Freya, he and his men would have to make their way across a bridge already strewn with Canadian dead.

When the Saskatchewans’ commander, Lieutenant Colonel Cecil Merritt, saw what Hawkins saw, he ran to the bridge, calling on his men to ignore the rain of mortars and bodies and the growing pools of blood. “Come on over,” he shouted. “They can’t hit anything. There’s nothing to worry about here.” This act of bravery earned him the Victoria Cross. Some 150 men, including Hawkins’ party, crossed the bridge but were soon held up by machine gun fire from a German pillbox. Merritt located the bunker’s blind spot, crept forward, and when the machine gunner paused (probably to reload), rose and lobbed grenades through its slits. A lawyer in Vancouver before the war, he would later recommend bombing a pillbox “before breakfast.” With tenuous control of Green Beach, on which the Winnipeg-based Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders* were now suffering their own agony, Merritt’s men pushed into Pourville. In one house, they discovered a group of Germans in flagrante delicto with les collaborateurs horizontales; in others, they engaged the enemy in hand-to-hand combat. Meanwhile, with the pillbox destroyed, Hawkins’ party managed to close in on Freya, only to find its entrance so well defended that he needn’t have worried about Nissenthall being captured. If they mounted a frontal attack, they would be killed.

Just after 0500 hours the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry (the Rileys) and the Windsor-based Essex Scottish approached Dieppe’s stony Red and White Beaches, while five Hurricane squadrons attacked German positions on the eastern headlands. In the rosy light of dawn, the troops could see the planes flying in low from the English Channel, the explosions on the shore, and the puffs of exploding anti-aircraft shells. But it was too little too late. As Hauptmann Schnösenberg said afterward, “Not even one [German] weapon was destroyed.” Some soldiers cursed the so-called “Hurricane bombardment” (“Is that all? “), not realizing that more than a dozen Canadian airmen had been shot down, of whom five died. One of them was Sergeant Stirling David Banks, whose Hurricane was so badly damaged that it crashed into the Channel. Pilot Officer John Godfrey, who was escorting the Hurricanes, flew down the middle of a tree-lined gully into a curtain of ack-ack fire that blew away the plane’s tail in front of him, costing another Canadian airman his life.

The Rileys started dying even before they touched down; a mortar exploded among some torpedoes, shredding all but two of the men in one boat. The Scottish, who had landed to the left of the three-storey casino overlooking the beach, had better luck—until they reached the second belt of concertina wire. The 800-metre stretch of beach was under heavy fire from machine guns and mortars. Men were falling everywhere, some carrying the very torpedoes they needed to blow up the wire. Finally, a private selflessly threw himself on it so his comrades could advance through the kill zone to the seawall, but by then, after only twenty minutes, 40 percent of his regiment lay dead or wounded. A few men made it as far as the promenade and onto Boulevard de Verdun, where, tipped off by a brave Frenchman, they ambushed a truckload of German soldiers. However, German snipers soon forced them to return to the abattoir by the shore.

To decapitate the attack, the snipers concentrated on radio operators and officers. Yet, as a German Leutnant later said of the Canadians, “Nobody thought of giving up. Taking effective cover behind their dead comrades, they shot uninterruptedly [if in vain] at our positions.”

Library and Archives Canada/C-014160Canadian casualties lie among damaged landing craft and Churchill tanks.

Library and Archives Canada/C-014160Canadian casualties lie among damaged landing craft and Churchill tanks.The carnival of death worsened when boats carrying the Calgary Tanks approached Red Beach at around 0530 hours. Captain John Foote, the Rileys’ Presbyterian padre, saw a burst of light above one landing craft’s gun, and, he said later, “all the Navy fellows just disappeared in one big blob” of smoke. Of the twenty-nine tanks deployed, two sank and twelve threw their tracks on the fine-grained, flinty chert or took hits in their tracks. Immobilized, they nevertheless fired at the headlands, providing some protection to the men pinned down on the beach. Thirteen tanks (one driven by a lieutenant whose face was burned to a crisp when a German shell ignited a hydrogen cylinder in his tank before it landed) made it over the seawall and onto the promenade. What stopped them from breaking into Dieppe, where Nissenthall hoped to employ one of the tanks to blast his way into Freya, were concrete obstacles that blocked the promenade’s exits. Removing them was the job of sappers, or combat engineers, dozens of whom were killed trying. Two of them died instantly when a bullet or a mortar hit a third’s thirty-kilogram, explosive-laden backpack. The only sappers who managed to reach an obstacle found their explosives too weak to destroy it.

Amid the maelstrom, Riley captain Denis Whitaker calculated that the fifty-metre gauntlet to the casino offered no worse odds than remaining on the beach. He and his men made a run for it, and when they got there many of the Germans inside quickly surrendered. The building gave them some protection and a way into Dieppe, but moments after they entered the town a fusillade forced Whitaker and a few men to dive into a shack, where they lay in fetid muck, “feeling great revulsion for every German alive,” he said, before exchanging the “crap” of the shack-cum-latrine for the machine gun fire that cut some of them down. Those who made it into Dieppe were astonished to see a Frenchwoman carrying bread in a basket, oblivious to the snipers. But not all of the “civilians” were doing their marketing: some acted as spotters for the snipers.

As the Germans picked off radio operators, the complicated inter-service, inter-ship, inter-brigade communications plan (which included relays to and from England) broke down, leaving Roberts on the command ship, HMS Calpe, with no clear picture of the battle; equally in the dark was Acting Commander Ian Fleming on HMS Fernie, where he awaited news of the commandos’ attacks. The carnage on Blue Beach should have prompted a call for withdrawal, but around 0700 hours Captain Hughes-Hallett reported that the landing there “has been effected with light casualties and no damage to craft.” Incorrect messages that the Saskatchewans were in Pourville in force and that Freya had fallen led Roberts to assume that German positions on the headlands beyond Green Beach would soon collapse. Information about what was taking place on Red and White Beaches was equally poor. At 0620 hours, Calpe received a cryptic message from the Rileys (“Impossible to land troops”), which was glossed over, because ten minutes earlier another message (“Essex Scottish across the beaches and in houses”) had painted a rosier picture. Some Scottish soldiers had in fact penetrated Dieppe, but most were dead or pinned to the beaches. Unaware that the words “any more” had been omitted from the Rileys’ message, Roberts ordered in his floating reserve, Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal.

At around 0700 hours, the Fusiliers reached a point more or less in line with the spire, dimly visible through the smoke, of Notre Dame de Bonsecours, which shared its name with the oldest church in the regiment’s hometown. An artillery fusillade sank two boats 200 metres from shore and forced several others too far west, putting hundreds of men out of the fight—but directly under cliffs from which the Germans rained down hand grenades. Two groups of Fusiliers made it into Dieppe. One destroyed a pillbox before making its way to the Bassin du Canada, named for the sailors who voyaged to New France in the 1600s. Sergeant Major Lucien Dumais led another in a dash to the casino, where they joined the Rileys in flushing out Germans. At one point, Dumais fired into a window in which he had spotted the muzzle of a gun, and a few minutes later a German crawled into the solarium. “I drew faster than he did,” Dumais said later, “so I was alive and he was dead.”

Unable to break into Freya, Nissenthall reasoned that if he cut the radar station’s telephone lines the operators inside would turn to their radio, whose signals could be intercepted and decoded. Accordingly, as more Fusiliers died, joining what was left of the Rileys and the Essex Scottish on the beach, and RAF and RCAF planes engaged in dogfights with the Luftwaffe in the war’s largest air battle, Nissenthall readied himself to crawl out from the brush behind the radar station. Fortified by a tomato a French girl had given him, a Benzedrine pill, a gulp of illicit rum from a comrade’s water bottle, and not least the story of David and Goliath, he inched forward, flak pinging off his helmet, the ground on which he crawled littered with shrapnel and spent machine gun shell casings. To cut the highest of the eight lines, he had to stand on the lowest, so that when he was most likely to be spotted by a sentry he made an easy target. Fortunately, it didn’t take long, and after cutting the last of the lines, the one on which he was standing, he fell down the hill onto a patch of ground, where he barely escaped being killed by machine guns fired from about a kilometre away. As Hawkins led Nissenthall to the casino, England picked up Freya’s signal.

While Operation Jubilee’s planners knew it would be a “near-run thing,” they had reason to feel optimistic. Though smaller, the raid on Saint-Nazaire had succeeded, as had one by many of these same Canadian troops on Spitsbergen, Norway, a year earlier. But by 0905 hours, the first part of the signal for withdrawal, “Vanquish 1030 hours” had mutated from the transitive verb meaning “to overcome in battle” to the past participle, “vanquished,” that describes a defeated army.

Delayed until 1100 hours, to allow for the laying of smoke, the returning landing craft gave the Germans fresh targets. At Blue Beach, where stretcher-bearer Private Ron Beal had run out of bandages and morphine—and where he discovered that nothing in his training had prepared him for the sight of men whose arms and legs had been torn away, or the nauseous smell of blood, cordite, and human viscera—heavy fire prevented the boats from landing. Within minutes of touchdown, six of the first eight boats at Red Beach were burning hulks, and dozens of naval ratings were dead or wounded. One Canadian seaman fought back vainly with a Tommy gun, and after taking a bullet in the chest died with the Nelsonian flourish “I am afraid I am hit, sir.”

German machine gun and mortar fire, and now strafing runs, broke “beach control.” Men followed the “one man, any boat” principle, resulting in overloaded boats that capsized, killing more men. On some boats, anguished ratings screamed at petrified men (this being 1942, most could not swim) to release their grips on propeller housings. The Germans had been ordered not just to repel the invaders but to destroy them, so when a boat from Green Beach sank 200 metres from seawall, snipers picked off the survivors. Still, there were many acts of courage. Some men saved others by staging rearguard actions, ensuring their own capture. Lieutenant W. G. Cunningham, for example, took Corporal Alfred Ernest Coxford to hunt a machine gunner above Green Beach who was cutting off their comrades’ escape route. Having bent the rules to go to Dieppe (and having fired a Sten gun at least once), the burly Chaplain Foote should have climbed onto a boat; instead, he carried wounded men to the boats and was captured as a prisoner of war, for which he earned the Victoria Cross.

Library and Archives Canada PA200058Captured Canadian troops are marched through the streets of Dieppe, following Operation Jubilee.

Library and Archives Canada PA200058Captured Canadian troops are marched through the streets of Dieppe, following Operation Jubilee.At one point, under the fleeting cover of a smoke bomb, a number of men, including Hawkins and Nissenthall, rushed from the casino toward the boats. Over the slippery rocks, past the moaning wounded and now mute dead, Hawkins, revolver in hand, ran behind Nissenthall, who remembers hearing a German shouting to fire at the man wearing the “blau” shirt. When they reached the water, Nissenthall dove in, but to shed extra weight Hawkins had to stop long enough to pull off the woollen sweater his fiancée had knitted for him. Luckily, the Germans were focused on the man in RAF blue, swimming a ragged line past the floating bodies. Both men were good swimmers, but nothing could shield them from the concussive force of the mortars exploding around them. Despite the tumult, what felt like sleep crept over Nissenthall, a Jew who had earlier paused on the beach to say Kaddish over a Roman Catholic who had given his life for him. Nissenthall was saved from a watery death when his head rammed against the half-raised ramp of a landing craft, and a rating pulled him aboard before rushing to the other side to haul in Hawkins. Whitaker, too, made it to a boat, but soon experienced the commander’s horror: having the life of one of his men slip from his wet grasp.

Around 0800 hours, shortly before the Royals surrendered, the guns on Blue Beach fell silent for a few moments, as both armies watched a Canadian soldier scale a cliff in an attempt to silence a German machine gun. The bullet that killed him was legal, as were those aimed at anything that moved on the beach; as long as Royal Navy destroyers continued to fire at German positions, German soldiers could fire on their attackers at will.

Sometime around 1300 hours, Calpe, her decks slick with the blood of hundreds of wounded men and, like the other ships, pockmarked by falling flak, risked heavy fire by closing on Red Beach to pick up whoever could swim to her. White flags soon fluttered in the breeze above the beach, where Canadian blood had already turned brown. About three and a half hours later, Catto led his small force out of the woods, and Schnösenberg shook his hand in what he called “the last noble and fair gesture…in the war.” The German soldiers who advanced after Fusilier Dumais raised his yellowed handkerchief were more threatening, but in the end they responded correctly to his surrender.

In the years to come, Canadian prisoners of war would endure numerous violations of the Geneva Convention. They suffered unsanitary conditions and were denied food in the boxcars that transported them to Germany. They were punished collectively and often denied Red Cross parcels. Some were forced to work as slave labourers in dangerous mines. In the winter of 1944–45, food and shelter were all but absent during the hunger marches, on which many Canadians died. Even before the strain of war dissolved Germany’s economy, they were fed black bread containing sawdust, meagre rations of often-rotten potatoes, and watery cabbage soup. One POW recalls a day when the source of the soup’s protein and fat was a “horse’s cock.”

But on the afternoon of August 19, 1942, all of this lay in the future—as did the indignity of being kept shackled for a year, and the drama of several daring escapes (one by Dumais) from the train that bore the Canadian prisoners to Germany and, later, from the POW camps. While the afternoon sun beat down on the beaches of Dieppe, now crawling with German soldiers, some tending the wounded, others surveying the detritus of war, an oily tide crept up the beach, strewn with the dead and wounded who wore the maple leaf on their shoulder.

The memory of Dieppe owes much to the public relations war that followed. Even before Roberts’ command ship and the fire boat carrying Nissenthall and Hawkins reached England, newspapers in the UK and Canada were hailing Operation Jubilee as a victory. “Canadians Spearhead Battle at Dieppe…Help Smash Nazi Opposition” crowed a headline in the Toronto Daily Star. But within hours, the Nazi radio program Germany Calling issued another story, in surprisingly idiomatic North American English: “Well, if it isn’t a second front, it darned well ought to be. Only a successful invasion of the Continent could justify the expenditure of life and matériel which is taking place.” And the next day, Lord Haw-Haw (a nickname for Germany Calling announcer William Joyce) blamed the “bloody fiasco” on the “unscrupulous and vainglorious amateur driven to despair by the demands of the Kremlin,” a reference to Churchill and his reputation, dating from the disaster at Gallipoli, for involving himself in military plans better left to experts.

The story quickly became fictional. The Star reported, “Canadians Lead Commando Raid on France: Objectives Gained after Day Long Battle.” But as the names of the dead began appearing in Canadian papers (of the 4,963 Canadians who sailed from England, 3,367 were taken prisoner, killed, or wounded—a 68 percent casualty rate), military officials realized they could not keep the scale of the disaster secret, even if they wanted to. Accordingly, Defence Minister Ralston appears to have followed the public relations plan drawn up in case Jubilee failed: “Lay extremely heavy stress on stories of personal heroism—through interviews, broadcasts, et cetera—in order to focus public attention on bravery rather than objectives not attained.” He told the Star that “in the next few days there will emerge many stories of dauntless heroism.” In one such story, twelve Fusiliers escaped permanent capture after clubbing a German with a lead pipe. Another celebrated Merritt’s single-handed attack on the German pillbox. Others were memorialized in October when seventy-five men were decorated with the Victoria Cross, Distinguished Service Orders, Military Crosses, and Military Medals (another ninety-one, it was announced, were “Mentioned in Despatches”).

Within days, however, Joseph Goebbels’ propaganda machine seized control, releasing newsreels of the fighting, and still photos showing long lines of shocked Canadian POWs. To counter the bad press, Canadian officials joined Mountbatten’s headquarters, as the public relations plan put it, in “stress[ing] the success of the operation as an essential test in the employment of substantial forces and heavy equipment.” This “lessons learned” argument had the virtue of restricting what could be said publicly about the raid. The Allies even resorted to cooking the books, releasing data that was often suspect. They claimed, for instance, to have shot down between ninety-six and 135 German planes and damaged 135 others, while the Luftwaffe reported a loss of only forty-eight aircraft and damages sustained to another twenty-four. For their part, Hermann Göring’s men shot down ninety-seven Allied aircraft, including thirteen of the RCAF‘s, and damaged another fifty-four.

Post-war historians tended to accept Mountbatten’s claim that failure at Dieppe led to success two years later at Normandy, but those who came after remain divided. Some, like Brigadier General Whitaker, argued that lessons were learned. Others, however, pointed to conceptual flaws that should have been self-evident, even in 1942. Combined Operations had disregarded wisdom acquired at Vimy and other battles: strongly fortified defensive positions cannot be attacked successfully without detailed planning, frequent rehearsals, and substantial firepower. Memoirs from the “ordinary ranks” tended to argue that they had been “done dirt” by Churchill and their own general, Roberts, who, according to one barracks story, said the raid would be “a piece of cake.” According to historian Bill Rawling, who recently completed an exhaustive analysis of the record, the Allies did learn that attacking Festung Europa (Fortress Europe) was different from attacking other coastal positions, not least because some of the defences were mobile. They also learned that landing craft flotillas needed to be specialized to avoid such navigational errors as the one that put half the Saskatchewans on the wrong side of the River Scie; and that sappers required specialized armoured vehicles to reach their targets. Still, the losses at Dieppe were an inordinately high price to pay for this knowledge.

The question remains: in the absence of the necessary firepower to neutralize the German defences, why did Mountbatten proceed with the attack? The answer is in part institutional. For Combined Operations, it came down to this: if not Dieppe now, what is left to do in 1942? The other factor was “magical thinking,” an uncritical faith in success. After all, Spitsbergen and Saint-Nazaire, although much smaller, had succeeded. And Hughes- Hallett had turned the German bombing raid that scuttled Operation Rutter into a positive: even if the Germans suspected it was aimed at Dieppe, he argued, they would never suspect that we would plan another raid on the same target so soon after.

Whatever the lessons learned, Dieppe quickly became a historical anomaly. It had no place in the victorious narrative that begins with Canada’s role in Operation Avalanche and the invasion of Italy, and continues through Juno Beach and into northwestern Europe. Sadly, despite the Canadians’ undaunted courage—which their German opponents freely acknowledged—Dieppe became a military metaphor for disaster.

The base at Newhaven, in southern England, was overwhelmed with caring for the battle’s survivors, so Hawkins and Nissenthall spent the night on a warehouse floor. Somehow, they held their tempers the next morning when an officious military police officer woke them with a kick of his boot. Later, after Nissenthall reached Canadian Army headquarters, he was told he would have to use a pay phone if he wanted to call Air Vice Marshal Victor Tait, his commander in London. When he protested that he couldn’t use a public phone for a classified call, he was subjected to an interrogation by a Canadian lieutenant who feared that this dishevelled man, claiming to be an RAF officer but wearing a Royal Marine tunic, might be a German plant. Eventually, Nissenthall prevailed and was given an armed escort to Tait’s headquarters in London. The vice marshal knew that during the battle the radar station had suddenly started using its radio, and he surmised that Nissenthall had disabled its land lines. Now they could discuss what they were learning from Freya’s signals. As Nissenthall was about to leave, he asked Tait a very human question: “Did you think I’d get away with it? “

“You were the sort of person who would be successful,” answered Tait, adding that he “felt sure the Canadians would look after you.” The look on Nissenthall’s face must have raised the question, how would you know about Canadians? To which Tait responded simply, “I’m Canadian myself.”

*A previous version of this article incorrectly identified the name of the regiment.

This appeared in the September 2012 issue.