In the small break room at the back of the Atlantic Funeral Home in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, where she works as a funeral director and embalmer, Patricia De Freitas eats fast. She paces in front of the counter and spears pieces of olive and chicken with a fork, watching the clock as she chews. In a few minutes, the family of a dead man will walk through the front doors to identify his body. De Freitas rinses her Tupperware. To the right of the sink is a smaller room, its large industrial shelves stacked with jumbo tissue boxes. A soft, swaying trumpet solo plays over the speakers.

She walks out of the break room and moves quickly through a series of doors to meet her colleague James Harris, whose gloved hands have spent twenty-nine years preparing bodies for services and viewings. De Freitas wears the same dark-blue polyester as the men she works with, but instead of pants, she has a knee-length skirt and instead of dress shoes, black pumps. She and Harris have just dressed and groomed the dead man’s body for the last time. Now he lies on a mattress filled with wood shavings inside a plain, flat-top metal casket covered in blue fabric.

De Freitas and Harris push the casket through another doorway, this time into the funeral home’s chapel. They roll the man to the front of the pews and frame his casket with two tall lamps. De Freitas bends down to pick rogue pieces of lint and tissue off the chapel’s carpet and straightens the bibles at each pew.

After stepping back to check the man’s placement, she turns away quickly. Her face softens as she starts down the chapel’s aisle, readying herself to open the large wooden doors to the man’s wife and children, who are waiting on the other side. It’s a short walk.

Early humans began burying and burning and leaving their dead for the birds before they developed agriculture. Before they began drawing in caves. Before they reached the continent of Australia. Fifty thousand years later, Tutankhamen is mummified in Egypt. A few thousand years after that, Chinese emperor Qin Shi Huang is buried with a mass of terracotta warriors. Civilizations across the globe build funeral pyres and perform ritual sacrifices. Burial caves are carved into the sides of mountains, and flags are draped over wooden coffins.

The traditions that surround death in today’s Western world are not only the result of our fluctuating social and emotional values. The ways we prepare bodies, bury, cremate and say goodbye are also products and services delivered by a highly specialized and regulated industry. An industry that, more than 150 years ago, began to transfer what was once done by the hands of family into the hands of trained professionals.

After Mary Todd Lincoln’s husband was assassinated, she called for a man named Charles DeCosta Brown, who had been preparing the bodies of dead soldiers since the Civil War began, to embalm her husband. Brown agreed, and his assistant Henry Cattell drained the blood of Lincoln out through his jugular. Cattell made an incision in Lincoln’s groin next, into which he pumped a solution of zinc and chloride. After Cattell dressed the president, Brown accompanied his body on a funeral train that travelled through 180 cities and seven states back to Lincoln’s home in Illinois. Lincoln was not the first public giant to be preserved—Alexander the Great was reportedly transported home in a container of honey and British admiral Lord Nelson in a cask of brandy—but, for hundreds of thousands of mourners, Lincoln’s was the first embalmed body they were able to see up close.

Spurred by newfound popularity, undertakers and embalmers formed the Canadian National Funeral Directors’ Association in 1926. The association, now in partnership with the Funeral Service Association of Canada, developed a specific certification process centred on its own body of knowledge. This effectively shut out women, who were regarded in early twentieth-century trade journals as unfit to run businesses and emotionally incapable of handling death. These misconceptions extended into the 1950s and ’60s, with women largely shunned from the business unless they had been raised in a family-owned funeral home. The feminist movement in the 1970s and ’80s shifted the funeral industry, as it did countless others, leading the way for more women to move into jobs previously earmarked for men. In the last few decades of the century, the number of women in the field began to grow, and it continues to rise today. According to the Statistics Canada 2016 census, 42 percent of funeral directors in Canada are women, up from only 14 percent in 1991.

In Nova Scotia, the number of female funeral directors has grown as well, with women now making up more than a third of employed funeral directors in the province. Last year, seventeen students graduated as certified funeral directors and embalmers from the Funeral and Allied Health Services program offered through Nova Scotia Community College, the province’s only program for aspiring embalmers and funeral directors. Of those seventeen, eight identified as female. De Freitas is one of two current female funeral directors at Atlantic Funeral Home’s Dartmouth location, which has six director positions. De Freitas is relatively new to Atlantic’s team. But if it weren’t for a tragedy, she may not have entered the industry at all.

De Freitas’s son was born on May 1, 1996, and she named him Lee. He lived a little more than a year. His life was spent in hospitals, and her year was spent there too. She remembers sitting next to him as he slept, and she remembers holding his small body inside the walls of hospitals in New Brunswick, Quebec, and Ontario. Hours and hours were spent like that, her holding him. That was their world until, suddenly, it wasn’t.

A year after Lee was born, De Freitas walked into a funeral home in Saint John, New Brunswick, and said, “My son is dead.” In shock and pain, she had no idea what was supposed to happen next. Her son was dead. That was all. She cannot remember what the man who arranged her son’s funeral looked like or what his name was. But she remembers he was lovely. He listened with a kindness that made her feel supported in the midst of devastation.

The memory of her son’s funeral, and the kindness the funeral director showed her, continued to reverberate in De Freitas’s mind. She wanted the chance to help people the way that man had helped her. In 2011, she enrolled in NSCC’s funeral and allied health services program. Two years later, she graduated as the school’s top student and was hired as a funeral director and embalmer at Atlantic Funeral Home. De Freitas remembers thinking that the required navy-blue polyester suit was a small sign she was in the right place. Seven years later, divorced and the mother of two children on the cusp of adulthood, De Freitas continues to dress in a uniform she loves. Each morning, she arrives at the funeral home determined to help, walking the halls in quick, regimented steps, straightening the hem of her blazer as she moves.

In December 2014, De Freitas sat in the passenger seat of the funeral home’s transfer vehicle, a black minivan with the rear seats removed. Scott Cheverie, a colleague, was driving. De Freitas and Cheverie were that day’s two-person transfer crew. Transfers from the place of death to the funeral home happen around the clock; the call comes in and the crew goes out. The body is picked up from the bedroom, nursing home, or crumpled car, strapped into a stretcher, and loaded into the vehicle. Depending on the circumstances of death, the body is then taken to the coroner’s office, or directly to the funeral home.

In the middle of this particular shift, De Freitas’s cell phone rang. On the line was a colleague who told her to call her mother’s fiancé immediately. A bit unsettled, De Freitas dialled his number from the front seat, the van still moving.

“Patricia, I didn’t want to tell you this over the phone,” he said. “But your mother passed away last night.”

“No, no!” De Freitas cried out. “That’s not true,” she shouted, incredulous. “She isn’t dead!”

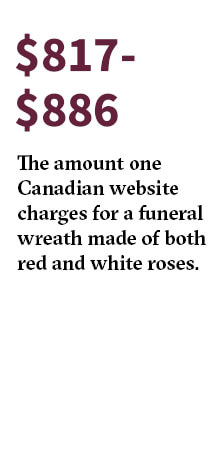

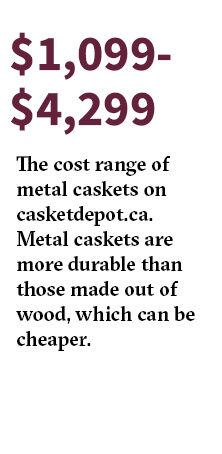

Instead, De Freitas called her sister and then the funeral home’s assistant manager, to request that he order a Primrose casket—an elegant model made of polished pink metal, its white lining embroidered with roses. De Freitas knew it was perfect.

Death for De Freitas had become a reality, a fully accepted and understood truth. But it was still a truth that could blindside. After three years of transfers and embalmings and services, she had a deeper understanding of grief than at any point in her life, but that didn’t make grief any easier to bear. She planned her mother’s funeral, but there was one thing she could not do. De Freitas couldn’t bear to embalm her mother. That she asked Harris to do, and Claire looked beautiful.

On a frigid day in January, De Freitas is in her office, at the head of a glass-topped table for six. The phone rings. It’s a father who has just driven with his wife up the winding driveway to the funeral home. The two of them are in the parking lot. Their seventeen-year-old son has died, they have not scheduled a meeting, and De Freitas has just a few minutes to prepare.

“Hello, I’m Patricia,” she says, shaking both of their hands, “I am so sorry to hear of your loss.” The air is quiet, a cocoon around the parents. De Freitas smiles sadly, but with encouragement, as the parents thank her and introduce themselves. Here they are, standing in a carpeted foyer making nice with a stranger. And De Freitas is the exact stranger no one wants to meet. She allows herself to feel their grief—its sharp, cutting newness. She may not know them, but she knows what they are feeling. She has been here before. They won’t go alone.