In the pre-dawn darkness of a Suday morning on November 14, 2004, a thirty-five-year-old Thai fisherman by the name of Wisthnuth-Tipong and four of his friends got into his traditional wooden long-tail boat, started up the 150-horsepower Honda motor, and left the beach near their village of Bang Niang to head for the open sea. The village of Bang Niang consists of about 500 local people, and a transient flux of foreigners. Like everyone else in the village, Wisthnuth’s extended family had profited from the phenomenal growth of the tourist industry over the last twenty years, and today’s boat crew all had good service jobs as well. Wisthnuth’s parents were building a large two-storey house on the other side of the busy coastal road, under the green hills of the National Park, a kilometre or two east of the village. Their beach provided something foreigners had always insisted on, a sunset view of the Andaman Sea. By mid-morning the beaches would be full of people, not only vacationers but also illegal construction workers from Burma and Malaysia, banging away on the new projects with their hand-forged iron tools.

But now, in the blackness before dawn, only the twinkle of security lights from the new hotels and bungalows were visible, stretching in an unbroken swath from the Royal Thai Navy base in the south to the far northern shore, a distance of some fifty kilometres. Wisthnuth had grown up here; only the dark line of the lumpy, irregular green hills was the same as he remembered it from his boyhood, part of a protected forest reserve.

Wisthnuth’s long-tail boat was named Pornsawan, which in Thai means “gift of heaven.” It was hand-built of redwood and teak, twenty-three gongs, or ribs, in length as the fishermen measure them, about twelve metres in all. Long-tails are designed for the coastal seas, aiming for a critical balance between cargo hauling, sea worthiness, and shallow draft for easy beaching over hidden rocks and coral. The Pornsawan was painted light green and red, earth colours, and like fishing boats the world over, she was named after the master’s daughter. As she headed out to sea where the reefs lay submerged at high tide, one of the fishermen began trailing his dakuwa, the sounding-weight. In the hands of an experienced boatman, this 300-gram lump of lead at the end of a hemp cord will tell you everything you need to know about the sea floor below—not only the depth, but whether you are striking sand, rock, or coral. The fishermen were looking for plagopon, red snapper, and sardines, platoo. They were also happy to take khung, wild shrimp. Despite the competition from sea farms, local buyers still favoured wild seafood, which they insist has a detectable difference in taste.

Wisthnuth remembers this day as calm and easy. A tranquil sky greeted them; the faintest light over the hooded mountains to the east promised more softness in the hours to come. “The sea is another world,” goes one Thai expression; and it means that the sea is not really part of our world, but a separate one, far distant from human reality. Going out on it is like dreaming, or praying to Lord Buddha, or even dying—another state of consciousness. And while all fishermen carry detailed maps in their heads of currents, tides, island smells, shorelines, reefs, and trade winds—things that lie within and below and contiguous to the sea—there is no map of the sea itself. It remains blank. Despite its many and enumerated qualities, it is essentially unknowable. “You do not know what is inside,” says one fisherman. They call it mahasamud—the great sea, too great to have mere qualities attach themselves to it, and going far beyond our words like raw, or cold. Closer to the Chinese word Tao, meaning a transcendent, primal energy.

The Thai word for beach is chaihard, meaning rim or edge, and the word for wave is krone. Bang Niang Beach, just north of Khaolak, lies at a latitude of about nine degrees north of the equator; accordingly, day and night are evenly matched in seasonless perpetuity, and the sky in the east begins to glow at 6 a.m. Perhaps glow is not the right word, for the change is more subtle than that. What really happens is that the stars and planets (which here hang so mysteriously and palpably in a thick tropical swarm of Chinese constellations) lose their connection to each other, like old men, former teammates who start by forgetting their names and end by forgetting what game exactly they used to play together in the park. The stars over the Andaman Sea go inward into themselves until they disappear, eventually leaving the sky hollow and undone. The dawn sky at this hour seems to grow even blacker, despite the cool fluorescence hanging tight to one corner. This was the traditional time, perhaps, when armies attacked—not dawn exactly, but at this off-kilter moment, when the stars have faded from sight and all chance of reckoning distance and direction is lost. This phase lasts in the tropics for about twenty minutes. Little ash-white sand crabs scuttle out of their holes and into the sloppy water before the birds can spot them; and the village dogs rouse themselves and bark at the first thing that moves.

Twenty minutes after the east has first begun to lighten, something unexpected happens. The sea, the surrounding hills, the few smudges of muddy clouds that play uncertainly between the two, all grow fatly cold and silver, and barren of purpose. Suddenly a charmless, metallic world appears out of nowhere, as if the desolation hidden from human eyes had dared to reveal itself at last during a change of stage sets, either by mishap or design. A chill is accentuated by an offshore breeze that whips over the foaming surf and the fine keening of wind-blown grit makes itself heard, for those who care to hear it. Then, at about 6:30, the bravado of another day takes over and the sun showers the palm fronds and the sharp, crested ocean with indelible marks of brilliant chromatic action. Birds warble and whoop knowingly; waves resolve themselves into familiar blue fixtures; the night cedes control to the flagrant minions of a triumphantly pink sun.

Wisthnuth and his crew had only reached two metres of water when he began feeling lucky; there was something special about this day. Didn’t he see a black cat up in a tree yesterday? And today was Sunday, his name day. He looked deep into the clarity of the sandy depths, and saw something none of them had ever seen before. There were fish down there. Lots of them. Fish in the transparent shallows, fish travelling in schools along the sandy bottom where there should have been one or two lone mackerel, hunting for tideblown plamuk, squid.

Like all sands, the sands of the Andaman Sea have their own microscopic qualities, signatures unique to themselves which make this beach distinguishable at once from all others as surely as the fingerprints of one person read differently from his six billion brothers and sisters. The sands of Bang Niang Beach are powdery fine; they squeak underfoot and take the impression of a rubber sandal with easy precision. Examined under a magnifying glass, the sand of Bang Niang is revealed to be made up of irregular beads of translucent quartz, mixed with creamy wedges of frosted silicates and microslabs of pyrites the colour of pale mangoes. A sparser fourth mineral is a pure black flake resembling ground pepper, jagged and organic-looking. Together these four types of grit create a beige hue that to the foreign eye suggests European skin tones. There was a similar colour in the Laurentian school set of pencils, an orange-white called flesh tone. The Thai word for this colour is namthon, or brown sugar. The Thai word for sand is sai.

But there was no word for what the fishermen saw that day. They cast their nets and began pulling in silvery mackerel, squid, sardines, red snapper, white snapper—they grew giddy with excitement at this unaccountable largesse. Fish, shoals of fish, in only four metres of clear seawater! When they should have been at least a kilometre or two out from shore, in depths of twenty metres or more. Yellow catfish, prawn, even a feral, gleaming tiger fish, more common to the waters far south, towards Indonesia, but which they recognized at once.

A bright yellow tiger fish comes boiling out of the nets and rockets against the boat’s wooden planks. Wisthnuth is loath to kill it before he has a chance to observe its strange beauty. The life of an ocean fish is a vivid rainbow that disappears irretrievably with a blow to its head, as if the fantastic final colours were the spectral thoughts of the creature itself, and not merely its inherited camouflage. Enough—Wisthnuth hits the tiger fish with a mallet. The men are laughing, ready for more, but the Gift of Heaven is bulging. They must stow their catch in ice crates on shore and hurry back, before these schools disappear.

Does Wisthnuth ask himself why he has caught so many fish, so easily? Not directly, no. There are other, better, more rewarding things to do than question one’s good fortune; and the time for reflection and analysis is still to come, after the catch is secure and they are safely back on shore. They will end this frantic day by catching an astonishing amount of fish—boatload after boatload. No one in the village had ever heard of such a thing, not even the grandfathers whose job it is to remember everything important that has happened to their people before them.

Unlike Wisthnuth, his younger brother Choite, thirty-four, speaks idiomatic English with an Australian accent, acquired as a part-time tour guide with a Thai travel agency. Wiry, fun-loving, and quick-witted, Choite is popular with his many friends and workmates. On Wednesday, December 23, 2004, he left his office in Phuket Town to attend a party at a nearby restaurant. It was “a terrific party, good fun,” he recalls. Afterwards, he packed his bags and drove his 100-cc motorcycle two hours north to Bang Niang, to be home in time for Christmas, dodging the heavy coastal traffic of diesel trucks and passenger buses all the way. The Bang Niang villagers are mostly Theravada Buddhist, some Muslim, but it is hard to ignore Christmas when up to 10,000 foreigners are celebrating it all around you. It’s a good time to be home, marking the end of the old year and making ready for the new one.

On the early morning of Sunday, December 26, at about 8 a.m., Choite was in his parents’ house—the temporary one, not the new one under construction. The night before, he had attended a dinner with family members and an Austrian couple, and they had had a great night, recounting wonderful stories, singing, telling risqué jokes, and the next morning he was remembering the laughter when his cellphone rang. It was his brother Wisthnuth.

He was on Bang Niang Beach, a kilometre away. Something strange was happening. The tide was supposed to be coming in; instead the water was going out, fast, though hardly anybody on the beach was paying attention. As the beach got bigger, the wet sand was exposed as far as the eye could see. “How far?” Choite asked. Maybe half a kilometre, and it was still receding, Wisthnuth replied. Maybe the sea was going dry?, his brother continued, half-seriously. “Okay, okay!” Choite cut him off. “I’ll call World Travel in Phuket Town. Maybe they know something.”

The company manager told him there had been an earthquake off Sumatra, a big one, an hour before. Patong, just two hours south of Bang Niang by motorcycle, was levelled at that moment. “Okay, okay,” Choite cut off the manager. He rang his brother back and told him that an earthquake’s after-effects had flattened Patong—and that Bang Niang Beach, where Wisthnuth was standing, would be next.

“It was lucky for me I went to school,” Choite recalls, “because I learned what happens when the sea goes dry.” “Tell people to leave the beach!” Choite cried out to his brother. “Right now!” Wisthnuth duly started telling people around him, and Choite could hear the words clearly through the cellphone. “Tell them to go the hills quickly!” he added frantically.

Wisthnuth handed his cellphone to a district policeman strolling along the shore, and to his relief Choite heard the policeman loudly repeat the message to bystanders, brusquely ordering them to move quickly off the beach.

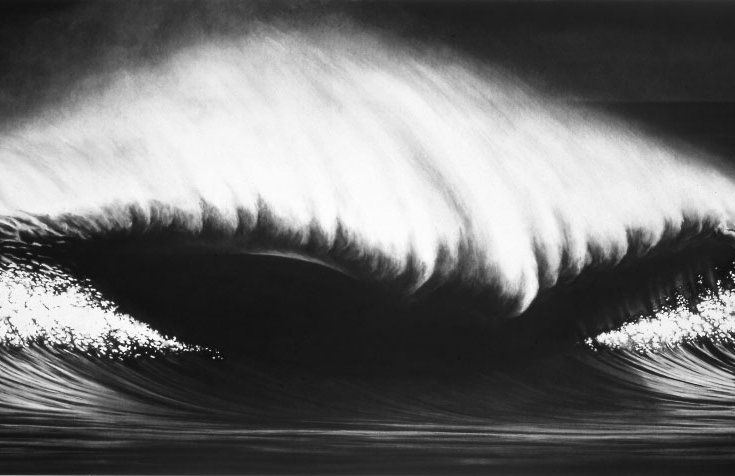

Choite cut the line and got on his motorcycle and headed straight down to the water, thinking, “I have to go see this thing myself.” Just as he left, he told his sister to pray and light some incense sticks for their brother-in-law, who was out alone on a fishing boat near Phra Thong Island, up the coast. Then he roared off down to the sand. The water off Bang Niang Beach was now one kilometre away and fishing boats were sitting in the wet sand. And in the distance he could see it: the wave, about a kilometre or so away. It was twisted and black, and moving very, very fast. It came to the first of the marooned long-tail boats and turned the twelve-metre vessel around on its stern and ate it. The boat completely disappeared and then the black wave ate each boat in turn. As they all disappeared, many foreigners stood there, watching, amazed by the sight, and Choite began shouting, still sitting on his bike, “Run back to the hill! Run, run!”

Choite knew he could pick up two people on his motorcycle, and might live with this knowledge for the rest of his days, but what he felt was the need to save his family, his brothers and sisters, his wife and children. He raced back to the temporary house, zigzagging his bike up through the sand, pushing off with his legs when he had to, going around obstacles, an abandoned truck full of cement bags, a load of wooden pallets. The traffic was growing as people ran to their cars. People were leaving the area; others were standing, looking out, mesmerized.

He made it across the coastal road and reached the temporary house, a kilometre up the gentle slope. Wisthnuth, his sister, his younger brother, and his own two children were already on motorcycles, ready to leave for the hills. All but his father and mother. His mother was praying at a Buddhist temple two kilometres north along the beach; but his father was right there, in the house, refusing to leave.

Choite had come with his passenger seat empty just for him, and now his father said, “No! Leave me! I want to die here, in our house!” Choite lost his patience. He got off his motorcycle, pulled his father to the door, and the old man saw the wave for the first time, coming up the frothing, chaotic beach, already filling itself with trees and cars and broken construction materials; he got behind Choite and they roared off in a convoy: Choite and his father were on the motorcycle; three nieces and Choite’s older daughter were on another bike; Choite’s younger brother and his sister were on a third two-wheeler; and his brother Wisthnuth, Choite’s baby daughter, and his sister were on a three-wheeler.

Choite believes that in another eleven seconds they would have all been dead. Choite said that if you were in a car or truck that day you likely would have died. Choite also believes that if you were on foot you were sure to die—unless you were very, very lucky. The family group of four bikes headed inland, up a ragged course into the green hills that rose 150 metres like a dragon’s back.

There was a forestry station located about thirty metres above sea level, but soon they could not see what was happening behind them through the dense trees of the forest reserve. The beach was completely obscured; all they could see was the perfect blue of the open ocean above the treeline, which, at this moment, around 10:30, was as serene and silent as any Sunday morning in days past. Could they hear anything from their first resting place at the forestry station? Only the cries of the people who had made it with them to the safety of the hill, by scrambling one way or another up the dense, slick red slope. Choite remembers hanging on tightly to his steel motorcycle key. Maybe he would have to use it again, go higher still? Nobody knew what was happening below.

And the wave itself, the black wave? Did it make a noise as it came toward them? Choite, three weeks later, stops, looks down at the littered Bang Niang sand under his feet, eyes once again registering the heaps of kids’ plastic beach sandals, the broken pink parasols, the strangely intact credit cards and return tickets to Frankfurt, looks up again and shakes his head as if to clear it. But nothing comes. “Don’t remember,” he says. He starts to shake, nerves pitched high. “I don’t remember if there was any sound. Just that it came very fast.”

Because he was the one local who could speak English up in the forest hill that day, he spent his time going around, warning the foreigners to stay put, stay up here, and not go back down below the trees—not even for a look. “No one can tell us what is going to happen after this,” he reasoned with them, “no one knows.” Stay, he urged them, understanding that while his schoolboy lessons had saved him and his family, neither reason nor experience could help them now. They had to be prepared to move again, that was all. He dissuaded an Australian who was frantic about his girlfriend and her friends, vacationing on distant Phi Phi Island, from setting off downhill on a hopeless journey. “I think they must be all right,” Choite reasoned with the man. “Phi Phi Island is about forty-seven kilometres from us, to the east. Very protected. The wave would have little force there.”

Did Choite know at the time that this was untrue? That flat, sandy Phi Phi Island was so devastated few people on it that morning would survive, for there was no place for them to go?

By noon the miserable group—maybe a hundred individuals in all—decided to move en masse to higher ground. The day lengthened into afternoon and the shadows of the trees grew longer. Near the forestry service main office, they discovered a second group of over a hundred people. And in a flat, open area, a third group of about a hundred also waited, huddled, and talked. Night came. It grew cold in the hills; the foreigners had no clothes, many of them, only bathing suits. Babies cried; there was weeping and no food. People had their cellphones with them and kept trying them, over and over again. Nothing. Nobody’s cellphone would work for days.

In the morning they finally came down. From the Royal Thai Navy base in the south to Phra Thong Island in the north, a distance of over fifty kilometres, everything was destroyed: major hotels, concrete bungalows, new strip malls. Broken glass and twisted rebars and dead bodies were heaped together indiscriminately. Of the more than 5,000 people killed in Thailand, some 4,000 had died in the area around Bang Niang, and now they were lying about everywhere, out on the open road and in ditches and under tree branches and in hidden, darker places where they would not be found for days, even weeks. The water took them where it wanted to, and left them there.

Choite went immediately to his parents’ house. It was gone. Only the concrete foundation remained, and there was a dead person in the yard with no clothes on her. Many of the bodies were like this, fully naked, as if the sea had intended to leave another mysterious sign, along with all the others. Choite choked on a breath and bent down to look: it was not his mother.

What happened to her defies the odds of probable storytelling. His mother was in the Buddhist temple, praying with a dozen or so other local people, and this temple, of course, was close to the beach. The worshippers could see people getting excited outside, and at first they thought Thai policemen had carried out another roundup of illegal Burmese work gangs, for there was a lot of shouting and running. Yes, those Burmese were distinctly foreign. They sported black and red head-kerchiefs like ratty sea pirates, and they worked for low wages, taking every dangerous construction job they could get. But now someone cried out, “Move, the water’s coming, very bad!” and the people in the temple all ran outside to a canopied pickup truck, the kind with open plank benches, a simple cage or frame to hold on to, and brightly decorated with images of smiling Kinerees and other Thai folk deities of good luck.

The truck was nearly full and starting to move when Choite’s middle-aged mother attempted to climb aboard. It took off and she fell backward, hard to the ground. With four or five others who were left behind, she limped back into the temple and stood there, irresolute, watching mutely as the first wave filled the floor to her ankles, then her knees. She saw the others slowly climbing the stone steps to the bell tower—and forced herself to follow, climbing its ten metres to safety.

All of the people in the bell tower survived. She learned the next day that everyone in the pickup truck had died within a minute of leaving her. It seemed as if the black water had chosen its own path here in Bang Niang, for when Choite’s mother climbed down from the bell tower one hour later, as soon as the water receded, she saw that some buildings had been unaccountably spared, while others—vaster, far more ambitious projects—had ceased to exist. The sacred Buddhist bell tower had survived, yet so had a tourist-retirement house built in a faux-Swiss Alpine style, while their own new house was part of a mass of foul garbage.

Her eyes, she told her family, could not take in what was. There was no sense to the scene; they kept returning to the few trees left standing, to the unbroken windows, to a steel gray Navy patrol boat that sat in a distant field, adrift on a cubist pond of broken pipes and lumber. Choite’s mother walked alone, along the coastal road, past bodies laid out by the sea on both sides of the macadam. Like the sandy beach down by the mild surf, the hard road 69 was swept clear, and passable, but now there was no place to go. Everything was blurry, indistinct; she does not remember crying. It was the world itself that had become a blur.

There were other escape stories. Choite’s third sister, Porntip, and her five-year-old son, out on Phra Thong Island, saw the wave coming and climbed a palm tree where the two of them stayed for an entire day and survived. More incredible was the story of her husband, the brother-in-law who was fishing off Phra Thong alone, who everyone had feared was lost. Nothing happened to him after all. The fisherman had been sitting in his long-tail boat, staring down at the empty water, coming to terms with the futility of yet another wasted morning. The fishing was unusually bad, as it had been for six weeks since Wisthnuth’s fantastic catch in mid-November. Suddenly, a flurry of activity under the boat tore his eyes from his inner reverie—colours, not fish, came roaring under his boat with scarcely a ripple showing on the surface. Red, yellow, black, brown, blue flashed by furiously. At some point the sign becomes the thing itself, and this happened right under his boat—a mass of flashing colours too busy to bother with him, and as he watched in shock they raced toward the distant shoreline with incalculable velocity, toward a scenic picture that began moving, slowly, then broke apart and remained a picture no longer.

Of Choite’s extended family, all but three were saved: his fourteen-year-old nephew had just arrived in Bang Niang that weekend and was sitting inside a beach restaurant, learning his new duties, when the wave crashed in; and Choite’s sister-in-law and her new baby, staying in the temporary house, were also torn away.

Choite, of course, did not see any of it; he was up in the hilltop, protected from seeing by the wall of trees. The only thing he had seen, he realized now, were the signs, and signs are always easier to read than the thing itself.

The signs he had seen, the signs that had told him something in nature was coming, were these: one, Wisthnuth’s boatloads of fish; two, the mature trees in the hills above Bang Niang, which he’d heard had mysteriously started falling in many places, one night about a week before the wave, in mid-December; and three, the scarcity of fish for at least six weeks before the sea went dry, when they had gone fishing every weekend and except for that one astounding day in November, had caught little. The current, too, had been much stronger than normal, and they could not reach the ocean floor with the usual 300-gram dakuwa, the lead sounding-weight. They had to use a one-kilogram weight just to find the bottom. Choite considered this last as a key sign. “Such a thing was incredible, so close to shore. Only twenty metres of water, and we couldn’t find the bottom, and no fish either. Nature was telling us something, but we were not thinking about it.”

Now, three weeks later, Bang Niang Beach was empty. Just as he remembered it from his childhood, twenty years ago. No vendors, no big neon umbrellas, no thatch huts. No people. Out on the blue Andaman Sea, a few Thai Navy vessels slowly patrolled the calm waters, looking for whatever the sea might have given up in last evening’s tide. And on the shore, mile after mile of twisted ruins where workers and volunteers sat under the trees eating box lunches, or stood in groups, listening to their briefings, or squatted under the shelter of solitary archways and porticos, sorting through documents, unused miniature shampoo bottles, wallets and towels and shoes.

Eventually the tourists will come back to these beaches—not this year, but maybe next year, and certainly the year after that. After they conceive and erect and consecrate a memorial to the dead, after they make a final decision about where to put it and what to say on it.

The word for sea in Thai is mahasamud, great sea; the word for sand beach is chaihard, rim or edge; and the word for wave is krone. Thai has two words for the colour blue: fa, which indicates light-filled blue, blue like the upper sky and which is also a popular nickname for a nice person, conveying hope and optimism; and nam-hgen, dark blue like the deep, unknowable sea. Whatever the final design, the monument might remind its visitors that the sea lapping at the pretty beach before them is a two-worded ocean.