Lt. General Roméo Dallaire’s Shake Hands with the Devil took me twenty sittings to read. It left me shaken, reeling, aghast, tormented. It is a book of astonishing power, a narrative account of the genocide, and the period leading up to the genocide, unsparing in its exposure of the madness that gripped the tiny country of Rwanda.

It is, all in all, a shocking read. Rwanda was either betrayed or abandoned by every possible actor: the United Nations Secretariat, the United Nations Security Council, the French, the Americans, the Belgians, the Organization of African Unity. It was as if some premeditated conspiracy was at work to show the world that, having crammed the Armenian genocide into the first part of the Twentieth Century, and the Holocaust into the middle, it now needed Rwanda as the finale.

On April 11, 1994, five days into the genocide, Roméo Dallaire, Canadian Force Commander of the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR), his entire emotional equilibrium in tatters, asks himself the ultimate question, “Where was God in all this horror? Where was God in the world’s response?”

The answer, alas, was that God was nowhere to be found.

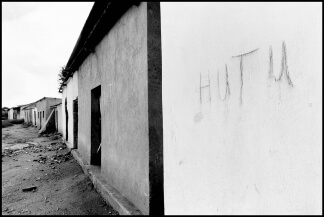

In a hundred days, between April 6, 1994, and the end of June, 1994, 800,000 people were slaughtered in the full view of the world, and the world raised not a finger. The carnage was carefully planned and executed by extremists of the majority Hutu ethnic group, against the minority Tutsi ethnic group, with a large number of Hutu moderates thrown in for good measure.

A Spartan rendering of the context would read as follows: For many months before the genocide, a plethora of political parties, some representing Hutu, some representing Tutsi, some representing both, some moderate, one or two dementedly extreme, pretended to overcome internecine differences and implement what was called “The Arusha Peace Agreement.” Also in the months prior to the genocide, increasingly hysterical public rhetoric, complemented by mysterious murderous attacks, targeted various leaders of the Tutsi population and some Hutu moderates. Throughout this same period, forces of the Rwandan Patriotic Front, led by Major General Paul Kagame, a Tutsi—soon to become president of Rwanda—were pressing south from the Uganda border, having taken refuge there for many years, as the then-existing Hutu regime engaged in pogroms sufficient to drive thousands of Tutsi into exile. Thus it was that, throughout the genocide, a civil war was raging. Both the war and the genocide started, officially, on April 6, 1994, when the president of Rwanda’s plane was shot down as it approached the airport in Kigali, the capital. The president of Burundi was also on board. To this day, no one knows who was responsible for the assassinations.

Within one-half hour of the plane crash, the apocalypse had begun. The question that haunts every page of Dallaire’s book is whether the genocide could have been prevented. His own answer is unequivocal: It absolutely could have been prevented. When you finally put the book down, it is impossible to draw any other conclusion.

Perhaps the most memorable missed opportunity occurred on January 11, 1994. Dallaire received word, indisputably reliable word, that there were weapons caches hidden around Kigali to be used by extremist civilian militias (gangs of well-armed thugs known as the Interahamwe) as soon as the signal was given to attack the Tutsi population. In previous months, lists of Tutsi names and addresses had been carefully assembled, and placed in the hands of various crazed militia and military commanders. Dallaire decided to raid and confiscate the arms caches, and wrote to New York, not so much to seek permission as to inform them of his plans.

To his astonishment, he was turned down flat by the triumvirate then in charge of peacekeeping: Kofi Annan, then Under-Secretary General of the Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO); Iqbal Riza, his deputy; and General Maurice Baril, a Canadian who had been seconded to DPKO as its military advisor, by the Canadian government.

Iqbal Riza signed the code cable from Kofi Annan. Not only did Riza reject Dallaire’s plan, but he insisted that Dallaire share the plan with the then president of Rwanda, who was a man completely beyond trust. Dallaire was stunned.

It was, on the part of the trio in New York, an appalling error in judgment.

But it also revealed the excruciating weakness at the heart of DPKO, for which DPKO was not primarily responsible. They couldn’t handle Rwanda. They had absolutely no capacity to run all the peacekeeping operations then in play (from the Balkans to Haiti). They were shockingly under-staffed, supernaturally bureaucratic, whipsawed by the Security Council, short of troop contingents, pathetically briefed by their political staff, and overworked to the point of self-immolation. Worse, they laboured under a Secretary-General, Boutros Boutros-Ghali, who had shown himself, where Rwanda was concerned, to be both uninterested and autocratic.

This impossible situation shackled Dallaire at every turn. On a daily basis, he confronted the questions that gnawed at his soul: What possible justification is there for continuing the facade of a real peacekeeping operation in Rwanda when you know it’s not working? When you ask for 5,000 troops and are reduced to half that, and then to a tenth of that; when the storm clouds are gathering; when scenes of massacres and atrocities are regularly reported even before the genocide begins. It is to Dallaire’s everlasting credit that he stuck it out, that he would not be bullied into submission by those in New York who felt that Rwandans were somehow not worth protecting.

Let me pause here to say that, for me, Dallaire’s book is, in places, a revelation. For two years, from 1998 to 2000, I was a member of a panel, appointed by the Organization of African Unity, to investigate the genocide in Rwanda. We did the best we could, hampered by time, budget, and access to secret materials. We interviewed Roméo Dallaire in two sessions over seven hours, and he greatly influenced our collective view of the genocide. But he wasn’t, understandably, able to share with us the confidential code cables and internal information that, as they appear throughout his book, provide telling, often definitive, insight into the events of 1994.

We’re still far too close to the Rwandan genocide—next year, after all, is but the tenth anniversary—to make final judgments. But Dallaire paints a picture that is both sweeping and persuasive. And he paints it with such obvious agony, regret, and personal trauma that it’s impossible to attribute malice to the interpretation.

It wasn’t just the problems at headquarters. The Americans used the Security Council to block any possible troop expansion, thereby dooming Rwanda. They played games with Dallaire, promising equipment and never delivering. They prevaricated about every transaction. They were so paralyzed by the deaths of the American marines in Somalia in 1993 that they were determined to compromise every other potential military intervention in Africa. Dallaire is so frustrated in his recounting of American behaviour that he actually blurts out, “Clinton’s fibbing dumbfounded me.”

The French, in particular, draw his ire, and they, in turn, couldn’t stand Dallaire, at one point actually writing the Secretary-General to ask that he be replaced. The denouement in the relationship, however, comes at the end of the genocide, when the French government launches “Operation Turquoise,” an alleged humanitarian intervention that was but a mask that allowed the genocidaires to escape into what was then Zaire, carrying artillery, heavy armour, anti-aircraft guns, and anti-tank systems. Well over a million people crossed the border, with no effort made to separate the civilians fleeing Kagame’s advance from the soldiers or gendarmerie or militias who were prosecuting the genocide. I have to say that providing safe haven for the butchers, and deliberately making it possible for them to continue the conflict on the other side of the border, was one of the most contemptible moments in the flow of horrific events.

The Belgians were a sad case. They lost ten soldiers in a brutal ambush on day two of the genocide, and then, reminiscent of the U.S. in Somalia, decided to pull out entirely, leaving Dallaire with perhaps 2,200 soldiers and military observers for the whole country.

The miserable, wretched truth is that almost nothing went right for Roméo Dallaire from beginning to end. Only superhuman determination and self-discipline saw him through, and those were clearly stretched beyond the breaking point, given the personal toll that was exacted. I can’t imagine how the man is still vertical. He suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder—he wouldn’t be human if he didn’t suffer from some debilitating condition.

Apart from all the anecdotes and the detailed documentation in the book that enhance our knowledge and bring the history to life, what is riveting is the descent into depravity surrounding Dallaire, and the hostile, incomparably venal personalities with whom he had to deal throughout those hallucinatory hundred days. Dallaire looked out his window and evil looked him back.

The most upsetting passages are undoubtedly the descriptive scenes of horror. They come at you like heat-seeking missiles, finding their target, leaving you gasping for breath:

We saw many faces of death during the genocide… For a long time I completely wiped the death masks of raped and sexually mutilated girls and women from my mind as if what had been done to them was the last thing that would send me over the edge. But if you looked you could see the evidence, even in the whitened skeletons. The legs bent and apart. A broken bottle, a rough branch, even a knife between them. Where the bodies were fresh, we saw what must have been semen pooled on and near the dead women and girls. There was always a lot of blood. Some male corpses had their genitals cut off, but many women and young girls had their breasts chopped off and their genitals crudely cut apart. They died in a position of total vulnerability, flat on their backs, with their legs bent and knees wide apart. It was the expression on their dead faces that assaulted me the most, a frieze of shock, pain and humiliation. For many years after I came home, I banished the memories of those faces from my mind, but they have come back, all too clearly.

Is it any wonder that Dallaire staggers through life? In chapter after chapter, throughout the period of the actual genocide, there are massacres in churches; the mortar bombing of hospitals; the casual killing of children; bodies floating in the river; the checking of documents at a thousand barricades leading to arbitrary death on the spot (rather like Mengele on the railway tracks, calmly pointing ‘left’ or ‘right’ as people were dispatched to the ovens); mass graves; the skeletal remains by the roadside; the murder of families while they were literally on the phone with unamir, pleading for protection. Dallaire doesn’t overdo it. Nor does he underdo it. But, by the time you’ve reached the finale, there is a full, aching realization of what really happened. Day by terrifying day.

There are two things about the book that I could not have anticipated. First, there is the startling chronology. Dallaire and his aides kept notes, sometimes by the hour. No other work on the Rwandan genocide that I know of is so meticulous in its exposition of events, of individual moments in time. The book is an intense, all-consuming personal diary, with no pages left blank.

Second, and more important, the book reveals how Dallaire’s every en-treaty was rejected time and time and time again. I had no idea. I knew that he tried desperately to make his case, to engage the New York authorities, to raise alarms, to rally the world. But I never imagined that he did it on an almost daily basis, and hit a brick wall of indifference, repudiation, contempt or silence with annihilating regularity. The worst, the absolute worst was the refusal of New York—during the first week, as the insane destruction spread throughout the land—to allow Dallaire to protect the local Rwandan population. When Iqbal Riza finally relents, after thousands upon thousands are dead, Dallaire writes: “I felt sickened as I read [the cable].”

The exasperating, helpless struggle took its toll. Slowly, inexorably, Roméo Dallaire unravels. It’s not just what he sees; it’s the sense of failure and the guilt of personal responsibility that he carries. He’s not personally responsible in any way, of course. In fact, you get the strong feeling that he, almost alone, moved heaven and earth in an attempt to prevent the catastrophe. But the failure wore him down. And then the nightmares took over. He was evacuated from Rwanda in August, 1994.

Lt. General Roméo Dallaire is revered by Canadians everywhere. When I finished the book, I could understand why. Here was a man who screamed into the void. No one listened, no one cared, no one heard. But he never stopped screaming. He valued every human life. He wept for every human loss. He never gave up.

There is a final chapter entitled “Conclusion.” It’s a touching chapter, a trifle naïve perhaps, combined with a reluctance to blame, and a search for solutions. Roméo Dallaire wants to believe, with all his heart, that Rwanda was some terrible aberration, that the world would never permit it again. Though he’s fairly hard-headed about the problems of a world that spawn terrorism and genocide, he’s a little too trusting. Still, it’s wonderful to think that a man who has been through the inferno, and who has been so palpably betrayed, still carries with him a sense of hope, even optimism.

This appeared in the November/December 2003 issue.