TRUE CRIME / DECEMBER 2024

The Strange Theft of a Priceless Churchill Portrait

The inside story of one of Canada’s most brazen, baffling, and mysterious art heists and how the police cracked it

BY BRETT POPPLEWELL

PHOTOGRAPHY BY DAVID KAWAI

Published 14:28, SEPT. 13, 2024

It wasn’t the cheap frame that gave the forgery away. Nor was it the photocopied image of the scowling Winston Churchill contained inside. It was the way it hung, crooked against the dark oak-panelled wall—a slight tilt, down and to the right.

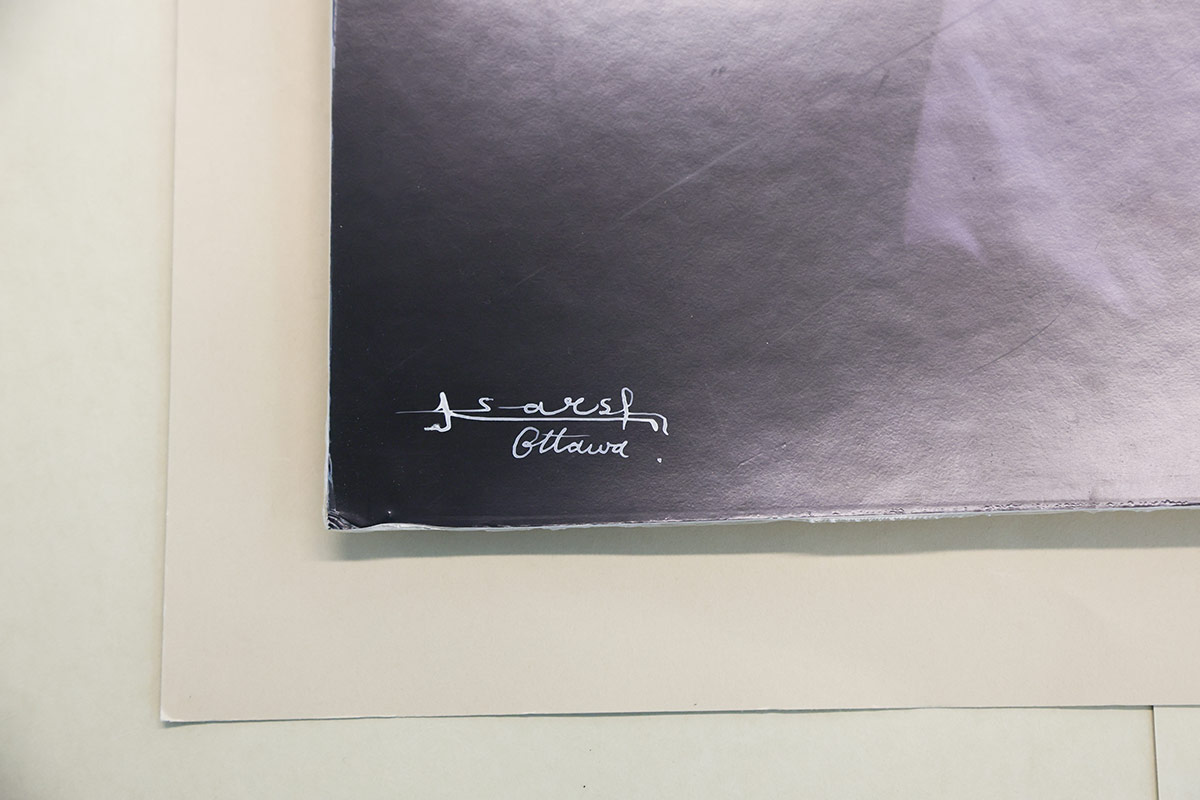

Bruno Lair couldn’t understand how the portrait had come detached from the wall. As head of engineering at the Fairmont Château Laurier, he had personally bolted it in place twenty-five years earlier, using what, at the time, was a state-of-the-art locking mechanism. Inside that frame, he’d been told, was one of the most valuable photographs in existence: a signed, rare, original copy of The Roaring Lion, captured by the greatest portrait photographer of the twentieth century. The signature—Karsh—in the bottom left corner of the frame was said to be priceless.

It bothered Lair to see his handiwork now dangling precariously from a wire, but he didn’t have time to make it right. It was shortly after 8 a.m. on a Tuesday in August 2022. The vast majority of the Château’s 426 rooms were still vacant as a result of COVID-19. And yet Lair was already struggling to keep up with the daily maintenance needs of the 112-year-old, 660,000-square-foot behemoth that had been his place of employ for more than thirty years. He lifted the portrait from the wall, walked it to an executive office nearby, and laid the frame on a table where he thought it would be safe.

Suddenly, the earpiece that kept Lair tuned in to internal communications crackled to life. An issue elsewhere in the hotel needed his attention. He closed the door behind him and got on with his day.

Lair didn’t know exactly how valuable the thing he’d just carried through the Château’s lobby actually was. But he understood it had once been gifted to the hotel by the late photographer himself. Lair could still remember the evening, a quarter century earlier, when Yousuf Karsh, on one of his last nights in the Château, thanked Lair and the rest of the hotel staff for their hospitality. Karsh had lived with his second wife, Estrellita, and their poodle in a suite on the third floor of the hotel. It was said that when the rich and famous had thoughts of immortality, they called for Karsh of Ottawa. Short, bald, and clad perpetually in suit and tie, Karsh travelled the world with his Calumet camera. Many of his most recognizable photographs—portraits of Pablo Picasso, Grace Kelly, George Bernard Shaw, Audrey Hepburn, Mother Teresa, Martin Luther King, Jr.—now hung in the Château. But none was quite so renowned as the one of Churchill, now featured on the back of the British £5 note.

It was the end of the week before Lair found time to rehang the portrait. He picked it up from the executive office and walked it back into the Château’s reading lounge, where it had previously hung among identically framed portraits of Ernest Hemingway, Albert Einstein, and others. That’s when he noticed that the lock he’d used to secure the portrait to the wall back in 1998 had been completely removed. He looked closely at the wooden frame. It seemed flimsier than what he remembered. Finally, he understood that the Churchill in his hands was not what he seemed.

A security officer from the hotel made the initial call to the police. It was Friday, August 19, 2022. Lair and the Château’s general manager, Geneviève Dumas, had already disassembled the frame and concluded that the print inside was just a photocopy glued to a piece of cardboard. They’d verified the portrait with Karsh’s long-time assistant, Jerry Fielder, in Boston; he needed just two seconds to confirm the forgery. Karsh signed his prints using a wooden stylus pen and Indian ink, but it was neither the pen used nor the brand of ink on the portrait which alerted Fielder that this was a fake. It was the signature itself.

The police took down Dumas’s information and said they’d follow up. But days passed. Meanwhile, guests and tourists aware of the photograph’s significance began asking what had happened to it. By the following Monday, journalists and camera crews were gathering in the hotel lobby. The theft made headlines in newspapers from Madrid to Sydney, London to New York. Dumas doesn’t know exactly how many journalists she spoke to that week but estimates it could have been dozens.

The calls from the media were still coming in when the police finally arrived. The delayed response surprised Dumas. The Roaring Lion was, for her, the Château’s Mona Lisa. She wasn’t convinced the authorities were taking it seriously. Those feelings became more complicated when the police informed her the evidence was tampered with and that she and Lair had to be fingerprinted and questioned. Soon the reading lounge was filled with investigators and specialists trained in tracking and retrieving stolen artifacts on the international market. They collected the forged portrait and took it to a secure police facility for forensic testing.

“They said they thought it was an inside job,” remembers Dumas. “I struggled to accept that.” Lair did too. Especially when the police asked him, point blank, if he’d stolen the portrait himself. Then they went on to ask the same question to other members of his staff.

From the moment it was first reported stolen to the moment, two years later, when the police finally revealed that they’d traced the Churchill portrait around the world to a collector’s living room in northwestern Italy, the disappearance of The Roaring Lion had attracted international intrigue.

For much of that time, the portrait’s whereabouts appeared destined to remain an unsolvable mystery. Though Akiva Geller, the Ottawa police detective tasked with its retrieval, remained optimistic, he kept his operations so quiet, many doubted the portrait would ever be found. As Robert K. Wittman, a former Federal Bureau of Investigation special agent who spent twenty years as a senior investigator with the US agency’s art theft and art fraud recovery unit, told me back in 2023: “As far as the police are concerned, there’s no difference between a stolen Monet and a stolen Chevrolet.” Art crime is generally considered property crime by police departments, and recovery efforts are rarely a top priority. But the theft of The Roaring Lion represented something more. “I think this is the most scandalous, mysterious art heist in Canada in the twenty-first century,” Wittman said.

As art capers go, the theft of Karsh’s Churchill seemed to be missing the Hollywood hallmarks that helped sear other heists into the public consciousness. Compare it, say, to the three men in balaclavas who rappelled from the roof of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts in 1972 to steal an estimated $2 million worth of jewellery and art before tripping an alarm. “What’s interesting about this case is that the theft probably occurred eight months before they actually discovered it,” Wittman explained, referring to The Roaring Lion. “It was a planned-out operation; it wasn’t a smash and grab.” Such an execution buys time for the thief, who faces a bigger and more complex challenge: turning a stolen masterpiece into cash. “The real trick in art crime,” said Wittman, “is not in the stealing; it’s in the selling.”

Experts long said the photograph’s real value was hard to peg. Previous sales of The Roaring Lion have fetched as much as $85,000 at auction. Though the actual stolen portrait managed to fetch only about $7,500 from a London auction house (significantly less than the $25,000 it was once insured for), Geller, as the lead investigator on the case, insists that the resale price didn’t matter to him as much as what it represented.

The problem for Geller, and for the investigators who worked with him, was that the specific portrait lifted from the Château was not easily discernible from the other original prints personally developed by Karsh and hand-signed over the course of the photographer’s career. Investigators knew the size of the photograph and that the signature in the bottom corner of the print had a unique curve to it, but the portrait wasn’t numbered and they didn’t know the year it was printed. As one of Canada’s leading art appraisers pointed out midway through the investigation, more than fifteen original copies of Karsh’s Roaring Lion were sold at auction within four months of the theft. There was no simple way for investigators to know for certain that the stolen Karsh wasn’t one of those sold.

Art crime investigations can take decades to close, if they close at all. Case in point: hardly any of the pieces from that old 1972 heist have been recovered. And, according to Wittman, these cases are generally really cracked only when someone tries to sell the stolen artwork. As a result, the missing piece can sometimes sit undetected in a thief’s attic for a generation. “I’ve seen that happen before. But I figured this piece would come back more quickly because of what it was. It’s not really a million-dollar piece that everyone’s going to know right off the bat. It’s a copy of a print, so there are quite a few out there. I thought it might be able to go slow under the radar for a while, but eventually, I figured, it would come back.”

Like any photograph, The Roaring Lion is a static representation of a moment in time. A simple image amplified and focused by hand, through delicate rotations of plates of glass, and filtered toward a tiny mirror contained inside a camera that projected the reflection toward a viewing screen. When Karsh opened the shutter for one-tenth of a second, he exposed an eight-by-ten sheet of light-sensitive nitrocellulose Kodak film to the reflection of Winston Churchill, creating a negative that later needed to be developed in darkness.

Karsh produced more than 370,000 negatives over the course of his career, and The Roaring Lion is just one of approximately 355,000 works held by Library and Archives Canada, many of which are sealed in temperature-controlled vaults inside a storage facility in Gatineau, Quebec. What sets the portrait apart from every other photograph ever taken is subject to interpretation. Some point to Karsh’s knack for composition and mastery of chiaroscuro lighting. Others speak of the strong, defiant, visibly aggrieved look on Churchill’s face. The photo helped propagate the wartime leader’s carefully cultivated image of a sophisticated yet savage bulldog.

On the day it was taken, December 30, 1941, Churchill was a desperate man. Britain and Canada had been at war against Germany for two years, and Churchill had spent much of that time underground while Heinkel bombers pulverized London. Now German U-Boats terrorized the North Atlantic, making his voyage to North America a precarious one at best. He’d scheduled the journey in haste, arriving in Washington, DC, just fifteen days after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbour triggered America’s entry into the war. His main objective: to direct America’s attention to Europe and the war with Germany.

Next, he travelled to Ottawa. Crowds gathered along the Rideau Canal and in front of the Château Laurier to watch his train pull into Ottawa Union Station. On the night he arrived, he sat in his room at Rideau Hall, working on a speech to deliver to Parliament. The following day, he stood in the House of Commons and spoke of the “Hitler tyranny, Japanese frenzy, and the Mussolini flop.” He recounted how, when Paris fell to the Nazis in June 1940, the French generals predicted England would “have her neck wrung like a chicken” within three weeks. “Some chicken,” Churchill scoffed, pausing for applause. “Some neck.”

Churchill exited the House of Commons, downed a scotch and soda, met with the official opposition and members of the country’s press gallery, then followed Mackenzie King toward the speaker’s office, where, unbeknownst to the British prime minister, his Canadian counterpart had invited a local portrait photographer to record a lasting image from the visit.

After watching Churchill’s speech from the public gallery above the Commons floor, Yousuf Karsh rushed to the speaker’s office to make sure he was ready for his subject when he arrived. The floodlights were warm and glowing by the time the unsuspecting Churchill was ushered into the room, a lit Havana cigar wedged between his lips. “What’s this? What’s this?” Churchill said upon spotting Karsh and his camera. The prime minister hadn’t consented to a portrait and didn’t want to sit for it either. Karsh moved quickly to calm Churchill and convince the mercurial leader to give him but a few moments of his time.

Karsh was thirty-three years old when he directed the sixty-seven-year-old Churchill toward a carefully lit spot in front of a wood-panelled wall. He’d been a photographer in Ottawa for ten years, operating out of a shared studio on Sparks Street. The fourth of seven children, his family had escaped the Armenian genocide by fleeing their homeland with nothing but what they could pack on a donkey’s back before boarding a ship to Canada. Once here, he changed his name to Joe to try to fit in but struggled with loneliness and a sense that he didn’t belong.

Photography was his escape. Karsh learned to use a camera under the guidance of his uncle, who operated a studio in Sherbrooke, Quebec. He continued his training in Boston before returning to Canada and striking out on his own. Karsh chose to set himself up in Ottawa, believing the capital would grant him unrivalled access to travelling dignitaries. By 1941, he was transitioning away from shooting everyday Ottawans and becoming recognized for imbuing his portraits with a grace and elegance that other photographers seemed unable to replicate. Ultimately, people would consider his prints the photographic equivalent of a Rembrandt.

Karsh ducked his head under the camera’s viewing cloth and adjusted the focus. The cigar was still lit in Churchill’s mouth. In a tale that he would repeat countless times, Karsh suggested the prime minister place the cigar in a nearby ashtray. Churchill ignored him, so Karsh pulled the cigar from his mouth and rushed back to his camera. “He looked so belligerent he could have devoured me,” Karsh later recalled. Then he pulled the trigger.

Churchill told him he could take another. Karsh reloaded his Calumet and looked back at the prime minister. Now Churchill was smiling. Karsh pulled the trigger once more.

The entire encounter was over in about five minutes.

In the eighty-three years since it was taken, The Roaring Lion has become one of the most iconic images of the twentieth century. Among those who have tried to explain its lasting appeal was Maria Tippett, Karsh’s biographer. To Tippett, the photo’s strength wasn’t just in what Karsh captured in the moment but what he accomplished afterward in his dark room (cropping out the extremities of the prime minister’s body and adding middle tones to his face and hands while toning down the wall behind his head). “Just like the Old Masters who made kings and queens appear more beautiful or more powerful than they were, Karsh had used artful manipulation to transform an unpromising negative of a tired, overweight, sick, and slightly annoyed man into a photograph of a heroic figure.”

It’s not clear whether Karsh immediately understood how powerful the image was. He developed the smiling Churchill as well as the scowling one and sent both for consideration to Saturday Night, Canada’s leading general interest magazine at the time. The magazine’s editors put the scowling portrait on the cover of their January 10, 1942, issue. Three weeks later, Life magazine, which dominated the American magazine market, reprinted it. The Illustrated London News quickly followed. Before long, The Roaring Lion was everywhere. Churchill himself began using the image on the covers of his own books.

Public interest in the photo remained high throughout Karsh’s career. Over the next five decades, he printed the image countless times in his dark room, always with the use of his own formulae of nitrates, sulphites, and chlorides, which his long-time assistant, Fielder, blended in stainless steel tubs. Once the process was complete, he would sign the front. At some point, one of his original prints found its way to the White House. Another ended up in the very room where the photo was captured, the speaker’s office on Parliament Hill.

The commercial success of The Roaring Lion transformed Karsh’s business. The photograph’s obvious strength in wartime propaganda led the Canadian government to dispatch him to England to photograph all the politicians and military leaders conducting the Allied war effort. Saturday Night pre-purchased the right to every black and white portrait he shot while in England. Maclean’s secured the rights to anything he shot in colour. He travelled with 750 pounds of photographic equipment and spent two months in 1943 photographing more than just Britain’s wartime leaders. He also focused his lens on celebrity. Ingrid Bergman, Humphrey Bogart, Judy Garland, Gregory Peck, Elizabeth Taylor—he shot them all. He spent the next decades capturing definitive images of some of the century’s most impactful characters. From Grace Kelly in New York City and Robert Oppenheimer in Princeton to Ernest Hemingway in Cuba and Nikita Khrushchev in Moscow.

At any point in his post-Churchill career, Karsh could easily have relocated his studio to Hollywood, Paris, London, or New York. Instead, he kept himself grounded in Ottawa, retreating, after every assignment, to his little house along the Rideau River where he liked to bird-watch with his first wife. In 1959, Solange was diagnosed with breast cancer. Karsh threw himself into his work throughout her illness, but when she died, in 1961, he was unable to cope with the loneliness.

He got remarried quickly, this time to a writer from Chicago twenty-one years younger. Estrellita Karsh relocated to Ottawa and, like his first wife, joined him on assignments around the world. By the early 1970s, Karsh was busier than ever. Though he experimented with colour, he found it artistically limiting. He found more satisfaction working in black and white, manipulating the middle tones of his prints to inject gravitas into his portraits. Jacques Cousteau, Fidel Castro, Muhammad Ali, Anne Murray, Margaret Thatcher, Carrie Fisher—one after another, they were filtered through the photographer’s lens. Sometimes, his famous subjects would come to Ottawa. Other times, he’d go to them. He kept the negatives for his 500 most famous portraits (including The Roaring Lion) secure inside the vault of a local Ottawa bank for decades.

He was forty-one years into his career in Ottawa when the opportunity emerged to relocate his studio to a seven-room suite on the sixth floor of the Château. The hotel’s many ornate archways, grand halls, and staircases had served as backdrops to Karsh’s portraits. From 1972 to 1992, every print he produced and signed came out of the studio he kept in the Château. By 1981, the hotel was his permanent home too. It didn’t take long for Karsh’s residency to add to the Château’s mythology. The hotel was the closest thing to a castle Ottawa had, and Karsh leaned into his own carefully crafted image of the modern photography equivalent of a Renaissance court painter.

Situated across the street from Parliament Hill, the granite, marble, and limestone hotel, with its copper roof and grandiose mix of neo-Gothic and French Châteauesque architecture, is an Ottawa landmark. Originally commissioned by an American railway magnate who died on the Titanic while trying to get back to Canada for the hotel’s grand opening, the Château Laurier has lodged kings and queens, presidents and celebrities, since it opened in 1912. But no one has ever lived in its suites for so long as Yousuf and Estrellita Karsh did—who, for sixteen years, called the hotel home.

Inside the Château, Karsh’s creative output flourished. As did his eccentricities. He once said that “to work in the Château is to be a citizen of a city inside a city.” When the hotel was busy, it had a buzz that was markedly different from that of the secluded home he’d kept along the Rideau. He appreciated its sprawling corridors, especially on cold winter days when he would wander the halls. There were days when the photographer wouldn’t even leave the hotel. He would rise early on the third floor, put on his suit, and take the elevator three stories up to his studio. One of the last significant dignitaries to visit him there was Nelson Mandela, in 1990. Two years later, Karsh cancelled his lease for his studio and slipped into retirement. He was eighty-four years old.

By then, the bulk of the negatives captured during his career had already been transported to Library and Archives Canada to be stored in perpetuity. He came out of retirement briefly, for one final celebrity commission, when he travelled to the White House to photograph Bill and Hillary Clinton. Then he donated his Calumet camera (along with eight others he used over the course of his career) to the Canada Science and Technology Museum.

He lived in the Château for four more years, snapping photos, as a sort of hobby, in his apartment suite but never again arranging another formal sitting. In 1997, together with Estrellita, he relocated to the Ritz-Carlton in Boston. He returned to the Château one last time the following year for a special event in his honour. On that trip, he gifted the hotel a selection of seven portraits that had been developed in his studio years earlier. Among them: a single copy of The Roaring Lion. At the time, the portraits were collectively valued at least at $50,000 (US). Individually framed, they were secured with locks to the walls of the Château’s reading lounge, with the understanding that they would remain displayed on permanent loan from the Karsh estate.

Karsh died four years later, in Boston, returning posthumously to Ottawa to be buried alongside his first wife in a plot next to that of Sir Wilfrid Laurier, namesake of the hotel he’d once called home.

For two years, Geneviève Dumas tried to keep the story of the stolen Churchill alive in the public consciousness. As general manager of the Château, it bothered her to know that the reading lounge in the heart of her hotel’s foyer remained the scene of an unsolved crime. Every time she walked through the lounge, she noticed the empty space on the wall where The Roaring Lion once hung.

Bruno Lair, the man who discovered the forgery, took the theft personally too. After all, he was the one who had secured the picture to the wall. As the months passed without news from the police, Lair began to believe that he’d never see the missing portrait again. It didn’t seem to him that anyone was on top of the investigation.

When we first spoke about the missing portrait back in 2023, Dumas was more reticent about her feelings. “For a time, the police weren’t even leading the investigation,” she said. “I was.”

It was Dumas who initially narrowed the window of time when the portrait was stolen. She put out an appeal through the media, asking members of the public to submit pictures they may have taken of the portrait in the reading lounge. She knew that the last known photograph of the real Churchill portrait appeared on the hotel’s own social media on December 25, 2021. The first known photo of the fake was snapped by the CBC’s senior Washington correspondent, Paul Hunter, on January 6, 2022, during an extended stay in Ottawa. Because of the date stamps on those two photos, the hotel and the police knew that the portrait was swapped out during a twelve-day period right as the Omicron variant of COVID-19 was spreading through the country, triggering mass cancellations at the hotel. The Château Laurier was functioning on skeletal staff by the time Hunter checked in.

“Everything was shut,” recalls Hunter. “I would walk into the lobby in the evening, and it was just a giant, dark, quiet, cavernous, beautiful, empty lobby. I don’t have a memory of seeing a single other guest during my two months there.” The reading lounge, generally abuzz with tourists and guests alike, was itself dark and quiet. Hunter had stayed at the hotel many times over the years and always navigated his way toward The Roaring Lion to admire it. His mother, who’d worked on Churchill’s re-election campaign during the 1950s, had kept a copy of that very print in their home while Hunter was growing up, and whenever he looked at it, he thought of her. After 8 p.m. on January 6, he pulled out his phone and snapped a photo of it.

Eight months later, he was driving down a country road when he heard news of the forgery. He pulled over and looked back through his phone for the photo he’d taken and couldn’t tell if it was real or not. He emailed the photo to Dumas, who forwarded it to the police. He’s still bewildered that he may have been one of just a handful of people staying at the hotel when the theft occurred. Until recently, he was saddened by the thought that he might never see that specific photograph again.

“The beauty of it, to me, was that it wasn’t in an art gallery. It was just on a wall in a room that anybody in Ottawa could walk into and just admire. It wasn’t behind plexiglass, it wasn’t behind guards; it was just there to be seen and enjoyed.”

That such a valuable portrait was on open display made it vulnerable. For years, the Churchill’s proximity to the hotel’s front desk and busy lobby may have kept it safe, but the moment the hotel became empty, the front desk was often unmanned. The opportunity emerged for someone to pick the locks that secured the portrait to the wall and place it in a suitcase or under a blanket and spirit it out the door.

One of Canada’s leading experts on art theft, Alain Lacoursière, insists that though the crime was clearly premeditated, it wasn’t necessarily complex. A former Montreal police officer who spent over twenty years investigating art-related crimes, Lacoursière says the locks could have been picked with a screwdriver and points out that the attention to detail in the forgery wasn’t overly high, because it didn’t need to be. All the thief needed was for that forgery to go undetected long enough for them to sell the photograph.

That the forgery ultimately bought the thief eight months is just one of the factors that made this case so hard to solve. Lacoursière suspects the portrait was stolen by someone with contacts inside the hotel who understood its value and knew it was unprotected. He doubts organized crime was even involved. “The mafia and the bikers and the people who used to be responsible for a lot of art theft in years past have moved on to Bitcoin and other things that can be stolen and traded online in a matter of minutes,” he says.

“Art theft in Canada is now so rare that there are no longer investigators whose jobs are dedicated to tracking these things down.”

In an age when the average person has a camera in their pocket and can use it to document their every action, Karsh’s portraits stand out. In 2014, it was estimated that 10 percent of all photos ever taken were shot in the previous twelve months. The number of photos taken in the years since has, it’s safe to say, only increased.

Amid this rising sea of indiscernible selfies and shared images, interest in Karsh’s work has persevered. The value of his prints goes up even as the famous people he photographed become increasingly unrecognizable. The other portraits he donated to the Château remain fixed to the reading lounge walls, monitored by newly installed cameras and magnetic alarms.

Much of what Karsh left behind remains preserved in the public domain. The camera he gifted to the Canada Science and Technology Museum is still in the collection—though it’s not the one he used to snap The Roaring Lion. According to the museum’s curator, that camera appears “to have been lost to history.” The little house he kept along the Rideau was torn down long ago, replaced by a subdivision, but inside the Château, visitors willing to pay $3,500 per night can rent the suite that served as his home during the last decades of his life. Meanwhile, the negatives he sent to Library and Archives Canada (including that of The Roaring Lion) are kept in a series of secure vaults located inside a two-year-old government preservation storage facility in Gatineau. They can be viewed by request.

At least three other Karsh original copies of The Roaring Lion are on display in Ottawa. One hangs locked to a wall near Karsh’s old Sparks Street studio in the private Rideau Club, where the photographer was a long-time member. Another hangs inside the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario. Another Churchill, which traditionally hangs in the speaker’s office, where the photo was taken, is currently in storage while the chamber undergoes renovation.

Meanwhile, the forgery that hung inside the Château for eight months remains in the custody of the Ottawa police, who treated it with a special chemical that blotched the print red while they searched for traces of human DNA. Stained and unframed, the print sits in a police warehouse in the city, resting atop a cardboard box on a shelf surrounded by other boxes containing shoelaces, rocks, pens, socks, and countless other items that have been collected from the scenes of other unsolved crimes in Ottawa’s history. Until recently, the police wouldn’t say much about the state of their investigation, referring questions back to the Château and its manager.

From her office inside the hotel, Dumas continued to seek leads on the missing portrait’s possible whereabouts. On her desk, she kept a folder of tips brought forth by members of the public, and she was eager to keep attention focused on what had been lost. “I worry it’s the only way,” she told me during an interview earlier this year, “for us to get the portrait back.”

Sometime after that conversation, The Walrus was tipped by a different source that the portrait had been found; however, the details were too vague to confirm. Dumas had been alerted as well. She doesn’t remember the exact date when she received a call from the Ottawa police to inform her that they’d found the stolen portrait. But she believes it was March 2024 and recalls that she was in her office and that the hair on her arms began to stand the moment she received the news. “I was beyond excited,” she says. “I had chills.”

Dumas had many questions, but the police had few answers. They said the portrait was now in Rome and that they’d traced it to an art collector in Genoa, but they were still piecing together how it had gotten there from Canada. The police had been working backward for months, having first noticed that a portrait matching the dimensions of the missing Roaring Lion had been sold by the auction house Sotheby’s in London on May 19, 2022—about nineteen weeks after its theft and thirteen weeks before the forgery was discovered. The hammer price: a paltry £4,200 ($7,500) plus commissions for a final total of £5,510. Neither the buyer—a thirty-four-year-old lawyer and contemporary and modern art enthusiast from Genoa, Italy, named Nicola Cassinelli—nor the auction house was aware that the portrait was stolen at the time of the transaction.

Speaking from his home in Genoa, Cassinelli now says that he was looking through an online catalogue of photographs being auctioned by Sotheby’s when he spotted The Roaring Lion and thought it would be perfect for his living room. It was described on the Sotheby’s website as an incredibly detailed print in generally good condition. It took Cassinelli two bids to win the auction. The portrait was encased in a cheap Ikea-like frame when it later arrived in the mail. Cassinelli hung it in a small corner of his living room but could admire it in peace only for a few months.

Sometime in October 2022, he says, someone from the auction house reached out to ask him not to resell the portrait to anyone else. They said the picture hanging on his wall may have been stolen but that they didn’t yet have evidence to prove it. “At that moment, I googled the news,” Cassinelli says. That’s when he learned what had transpired in Canada. He waited for someone from the police, or the auction house, to reach out and let him know the next steps. A year passed. As a lawyer, he knew that even if the portrait in his possession turned out to be the one stolen from the Château, there was nothing in Italian law that would oblige him to hand it over.

So he carried on admiring the portrait until November 2023, when a representative from Sotheby’s reached out again and asked for permission to share his contact with the police. By that point, London Metropolitan Police was working in conjunction with detective Akiva Geller to identify both the buyer and the seller. The police soon learned that the portrait had been shipped to London from overseas and that the seller was a Canadian man from a small town in Ontario.

It was around January 2024 when Cassinelli and Geller finally spoke on the phone. After Geller described the anomalies in Karsh’s signature, Cassinelli looked closely at the one hanging on his wall: it slanted downward near the end of the photographer’s name. “That’s ultimately when I knew,” Cassinelli recalls. “I had, unexpectedly, a piece of history in my living room. It was like having the Mona Lisa. I thought: Oh wow. How could it happen to me? ” On February 28, 2024, he walked into his local Carabinieri detachment and told Italian police that he understood himself to be in possession of stolen property. Before long, he says, a commander in the force’s heritage protection unit was dispatched to Genoa from Rome to meet with him and to ultimately take possession of the portrait. Though he was still out some of the money he’d paid to buy the portrait from the auction house, Cassinelli nonetheless handed it back. “Legally, my title was absolutely valid and effective, but I wanted to give it back to the hotel,” he says.

Once the portrait was in police custody in Rome, Geller turned his attention to the suspected thief in Canada. He called Dumas, gave her the name of the alleged culprit, and asked her to verify whether he had any known connection to the hotel. Dumas checked the name against the hotel records but found nothing. “He wasn’t a guest, and he wasn’t an employee either.”

On April 25, 2024, police arrested and charged a forty-three-year-old man from Powassan, Ontario, a small town located roughly 370 kilometres northwest of Ottawa. The next day, that man was ushered into an Ottawa courthouse and charged with mischief, forgery, theft, trafficking, and possession of property obtained by crime. His name is Jeffrey Wood. Four days later, he was released on bail, ordered to live with sureties and to not travel more than fifty kilometres from his residence.

Despite the outcome, Geller remains hesitant to share too much about how the case was cracked. “This is the most complex investigation that I’ve been a part of,” he says. “Early in this investigation, I recognized that the impact of this theft went beyond a piece of art stolen from a hotel.” The Ottawa police didn’t even notify the public that they’d made an arrest until September 11, when they issued a press release announcing that they were working closely with the Carabinieri and the portrait’s purchaser to ensure its safe return to Canada, where it will be remounted on that oak-panelled wall inside the Château with a new lock and increased security.

For his part, the Italian art lover who owned it for much of the past two years says he hopes, one day, to see The Roaring Lion hanging inside the Château, where it belongs. He misses it, sort of. Shortly after handing it over to the police, Cassinelli purchased a cheap replica from an online poster shop. That poster now hangs in place of the stolen original. “I just wanted to have it in my house,” he says. “It makes for something entertaining to talk about with friends over dinner.”