Cashing In, a new television dramatic comedy about a native- run casino on a scrubby reserve in southern Manitoba, may be a North American first. Billed as a cross between the and nbc series Las Vegas and cbc’s The Rez, it will surprise viewers for two reasons: it’s about sexy and rich Aboriginal people, and it’s funny.

Despair and the need to heal don’t motivate the characters in this comic soap opera — ambition does. The employees of the North Beach Casino want money, social status, and sex. The pit boss, Barry Jules, and his sidekick, Scott Daniels, are compiling “cleavage tapes” from the casino security videos to sell on the reserve. Barry is also sleeping with his boss’s forty-four-year-old, cocktail-inhaling wife, usually in a cramped, smelly trailer out back of the casino. Justin Tommy, the casino owner’s privileged, useless son, who is in Manitoba to learn the business, is chasing after a blonde lounge singer. But the series’ most compelling sexual tension is between gaming mogul Matthew Tommy and his vice-president, Liz McKendra. Matthew has banished Liz from Thundercloud International’s Toronto headquarters after she had an affair with her assistant. In Manitoba, her mission is to broker a land deal to facilitate the casino’s expansion. The land in question is owned by Matthew’s old rival, the millionaire rancher John Eagle, who rides horses, wears a buckskin jacket, and frets about protecting the fictional Stonewalker reserve wetlands. John has a crush on the lovely Liz. How will it all turn out? Will it be John or Matthew who ultimately takes Liz to bed? Will Justin get the girl and make something of himself?

Most of the mainstream TV dramas about native people are thoughtful but frequently bleak looks at a culture struggling with the after-effects of white colonization, like Moccasin Flats. But by far the most well known is North of 60 (1992–97), which starred Tina Keeper and Tom Jackson. First broadcast on and cbc and then syndicated around the world, it was lauded for exposing the reality of life in an isolated, winter-bound native community in the Northwest Territories. It left a lasting impression and influenced a generation of white and Aboriginal TV writers. But not everyone was a fan. After writing one episode, Ojibwa playwright and humorist Drew Hayden Taylor criticized the series in an article entitled “North of 60, South of Accurate.” “The consensus among most Native people was that Lynx River was the most depressing community in Canada,” says the forty-six-year-old Hayden Taylor, who lives on the Curve Lake reserve, northeast of Toronto. “Nobody ever laughed. It was like ‘What are they going to do to Tina Keeper this week?’ That show was very important, but what it lacked was the humour we have been using for years to survive the dark aspects of colonization.”

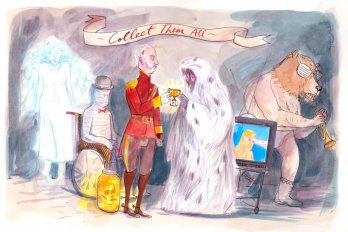

While there are lots of jokes about bingo, life on the reserve is largely ignored by the five novice native writers who wrote Cashing In as part of a joint training program between the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network and the National Screen Institute. The centre of the action is the opulently kitsch North Beach Casino, with its fake palm trees, blackjack tables, and beautiful people. There is some social commentary about compulsive gambling and the disparities between rich and poor natives, but overall the storylines are light and the tone goofy. “We’re playing with the assumptions people have about Aboriginal culture,” says Trevor Cameron, a Metis stand-up comic who started writing the comic animated children’s series Wapos Bay before working on Cashing In. “We don’t all use bedsheets for draperies. We have our own upper class.”

So does Cashing In mark a shift in Aboriginal culture’s sense of itself? It’s a sharp turn for aptn, concedes the network’s director of programming, Peter Strutt: “In the past, most of our shows have been introspective and based on traditional ways, which is what Aboriginal people wanted to explore. With Cashing In, we want to reach a broader audience. It’s more of a contemporary look at Aboriginal people, many of whom are successful and work alongside whites in casinos.” The network rejected the writing team’s first concept, a darker comic drama that drew the inevitable comparison to North of 60 (their writing coach was North of 60 screenwriter Peter Lauterman). “We wanted it to be sleek, sexy and fun,” says Strutt. “We didn’t want it to look Canadian.” The six half-hour episodes (co-produced by Manitoba- based Buffalo Gal Pictures and Animiki See Digital Productions, and picked up by Global) will be broadcast on Showcase.

While writing about tony elites might be a stretch for Aboriginal storytellers, making people laugh isn’t. In fact, being funny has been an integral part of Aboriginal culture for centuries, although until recently this was lost on most white observers. Canadian satirist Stephen Leacock once described the native as “probably the least humorous character recorded in history . . . To crack his enemies’ skull with a hatchet was about the limit of the sense of fun of a Seneca or a Pottawottomie.”

I was born in Manitoba, which has one of the largest Aboriginal populations in Canada and where race has divided whites and natives since well before the Red River Rebellion. While roughly 13 per cent of the province’s residents are native, they represent more than 60 per cent of the prison population. Aboriginal people are poorer than whites, and many have debilitating drug and alcohol problems. In Gimli, the Lake Winnipeg fishing community where I grew up, some fishermen resented “Indians,” as they were referred to, because they had treaty rights to fish. In Gimli, native people were often viewed as leeches on the state or objects of pity. For me, they appeared withdrawn, solemn, and completely foreign. When I first saw playwright Tomson Highway’s Dry Lips Oughta Move to Kapuskasing, it was a revelation, mainly because it was, in parts, hilarious. The clever and mischievous Trickster (or Nanabush, as it’s known in Ojibwa mythology) teases the mentally challenged Dickie Bird for constantly carrying a Catholic cross. “I traded mine in for sweetgrass,” says Nanabush, played by a graceful, plump Aboriginal woman. Bird later rapes Nanabush with his cross, but that’s Highway’s way: he makes us giggle with a joke, then shocks us with images of the graphic violence inflicted on natives in this country.

Highway believes his people’s silliness is rooted in language. In Me Funny, a collection of essays about native humour, the trilingual playwright writes that while English exists in the head and French in the heart and stomach, Cree “lives in the groin, in the sex organs . . . in the most fun-loving, the most pleasurable — not to mention the funniest- looking — part of the human corpus.” He says that fast repetitions of such Cree words as chicoutimi, chibougamau, or eemana-pitee-pitat (he’s pulling his tooth out) will tickle your sex organs and have you squirming with pleasure. Cashing In writer Mike Gosselin, a Metis from Saskatoon, believes humour is naturally present in cultures with strong oral traditions. Spinning a tall tale or telling a good joke is what native people do when they get together, he says: “It’s in the Aboriginal nature to make fun of each other and to tease and laugh heartily. There is nothing like going to visit people on the rez or sitting around with a mix of Metis, Aboriginal, even Inuit people. It’s incredible how many jokes there are.”

For decades, perhaps centuries, these jokes were lost on the non-native population. One of the first writers to bring native humour to mainstream Canada was novelist Thomas King, who created and performed in the popular and cbc radio serial Dead Dog Café Comedy Hour (1997–2001). The blessedly politically incorrect show featured King and two cohorts, Jasper Friendly Bear and Gracie Heavy Hand, trying to run a radio show out of a tourist trap restaurant in Blossom, Alberta. Dead Dog poked fun at bingo, bumbling Indian and Northern Affairs bureaucrats, and Aboriginal cuisine (in one of the most infamous and controversial episodes, Gracie threatened to wring a dog’s neck on air to make her favourite dish, puppy stew). At its heart, Dead Dog was political satire. King skewered both white privilege and his own people’s incompetent leaders. He once told a Globe and Mail reporter that natives are funny because they need the laughs. “I think it’s a survival strategy,” he said. “If life is so bad, you either kill yourself or you laugh. Colonized people can see humour as a strength, as a medicine.” Hayden Taylor, who edited Me Funny and directed Redskins, Tricksters and Puppy Stew, a documentary about the healing power of Aboriginal humour, agrees. Aboriginal people have used humour in the same way as Jews used vaudeville and black Americans stand-up, he says: “Humour kept us sane. It gave us power. It gave us privacy.”

Playwrights such as Highway and Hayden Taylor use comic theatre as an act of political resistance — to expose how natives have been brutalized by Canadian society since Jacques Cartier landed here in the sixteenth century, thrust a Catholic cross in the ground, and kidnapped several Iroquois to take back to France. In The Rez Sisters, Highway’s play about seven native women who hope to attend the biggest bingo in the world, the character Zhaboonigan describes an awful rape to the Trickster Nanabush, who appears in the form of a seagull. The at times humorous scene is meant to recall the gang rape of nineteen- year-old Helen Betty Osborne by a group of white men near The Pas, Manitoba, in 1971, an incident that helped spark the province’s comprehensive Aboriginal Justice Inquiry. Hayden Taylor believes Aboriginal storytelling has softened since The Rez Sisters made its debut in 1986. “For a decade, the stories coming out of native culture were dark, depressing, angry, bleak, and sad, which makes sense. When you have been oppressed and get your voice back, chances are you aren’t going to write a comedy. But perhaps some of the healing has taken place, and now we can afford to be funny.” He has written another aptn comedy, Mixed Blessings, about an Aboriginal waitress and a Ukrainian plumber. Not surprisingly, he applauds aptn for having the vision to lighten up (the network has also commissioned the Regina-based comedy troupe the Bionic Bannock Boys to write a pilot).

Cashing In writer Adam Garnet Jones, a twenty-seven-year-old, Toronto-based independent video maker who is part Cree and part Danish, says the TV series reflects a trend that’s been apparent in independent film and video circles for a few years: “There have been lots of comic works. I think there is a higher level of sophistication out there now. We know we can entertain people and engage them on many levels. It just doesn’t have to be brutal all the time.”

He isn’t sure how the native community will receive Cashing In. “When the series was done,” he says, “we looked at the show and asked ourselves, ‘Just how Indian is it?’ There are some people who are interested in taking the rez sensibility and humour and popularizing it. This show doesn’t do that. It’s all about being mainstream. We are taking a commercial template and putting it in an Aboriginal setting.” But traces of the rez outlook remain, particularly in Barry and Scott, the hosers taking pictures of breasts to make a bit of extra cash, who emerge as two of the funniest characters in the series. And there’s also a Trickster-like character, Trevor, a gay bartender and magician, who pokes fun at white society’s earnest fascination with native spirituality. In one scene, he fools a young blonde singer into believing he has special powers. She’s vomiting in the sink after discovering she has to replace pop star Chantal Kreviazuk as the casino’s feature act. Trevor waves his hand in front of her face with a wizard’s gesture, flips back his long, dark hair, and tells her she’s going to be a star. Of course, her performance is magnificent. “An Aboriginal audience will see he’s bullshitting, but a white audience might not,” says Garnet Jones, who wrote the episode.

I hope Cashing In maintains its slightly backwoods, frequently hilarious comic tone, which — if you can picture this — combines Beachcombers grit and Desperate Housewives glam (American television and rural Manitoba seem to be Cashing In’s main cultural influences). If the show is renewed, the writers would do well to highlight rather than sideline the rez sensibility. It’s their richest source of material.

As the history of American comedy illustrates, outsiders can penetrate the mainstream without losing their edge. Such popular African American comics as Richard Pryor, Chris Rock, and Eddie Murphy addressed racism head on and made whites laugh. Similarly, Jack Benny, George Burns, and Milton Berle brought the shtetl world view to America, massaging the oppressed Jewish immigrant experience into a popular art form and creating a comic style that has dominated American entertainment ever since. Although few of the characters on Seinfeld are identified as Jewish, their neurotic banter and brilliant comic timing are distinctly mensch. Jon Stewart’s take on the White House is also deeply rooted in Jewish political satire without being identified as such.

Who better to make fun of Canada than Aboriginal writers? The genius of Dead Dog Café was that it revealed how funny Canadian whites are to look at from the outside. Perhaps Aboriginal comic writers should be recruited as this country’s new comic voice (Air Farce has left a spot open). Imagine what the news would look like if This Hour Has 22 Minutes had an all-native cast? What if The Rick Mercer Report featured an Aboriginal correspondent? The possibilities are endless. But do we have the sense of humour to let it happen?