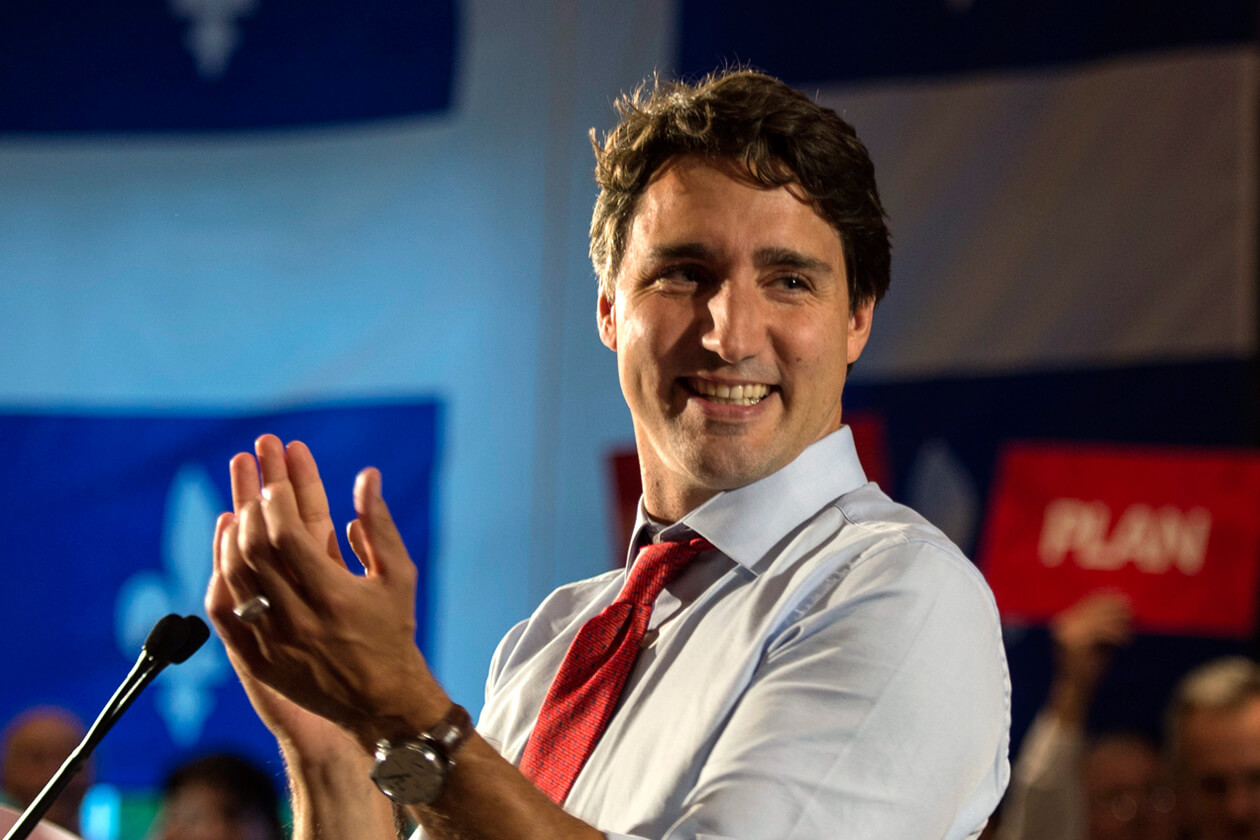

Three and a half years ago, in the bowels of Montreal’s Queen Elizabeth hotel, Justin Trudeau put down a nearly empty bottle of Molson Export and ascended to a nearby stage in his first public appearance as Canada’s twenty-third prime minister. The ensuing twenty-three-minute speech, in which Trudeau spun Wilfrid Laurier’s “sunny ways” catchphrase into a harbinger for his imminent tenure, was a particularly ebullient variation of what you’d expect from a man who ran and won on his own conspicuous optimism. Hyperpartisans in the room became visibly verklempt at his words; many journalists rolled their eyes as they shovelled quotes into their copy.

As a mantra, Trudeau’s “sunny ways” had surprising longevity: the government continued to peddle the conceit that it was inherently nicer, more wholesome, and less cynical than its opposition throughout most of its mandate. In turn, at least according to most polls, a majority of Canadians were prepared to give the benefit of the doubt to this article of faith.

Then, in early February, we learned the government had allegedly acted in a decidedly unsunny way. Former justice minister and attorney general Jody Wilson-Raybould testified before a parliamentary committee that the Prime Minister’s Office had pressured her to go easy on SNC-Lavalin, the Quebec-based engineering and construction behemoth facing a multitude of fraud and corruption charges. Wilson-Raybould described this pressure as inappropriate, political interference in a criminal prosecution—an allegation the prime minister and his aides denied.

For the Liberals, the fallout from the scandal was all the more precipitous if only because they had put themselves on such a high perch. Having sold Canadians on change and optimism, the party instead stood accused of indulging in the kind of old-school, rank political interference and Quebec-centric corporate favouritism associated with the Liberals from long before Justin Trudeau walked onto that stage in 2015. Polls dived, pundits waved fingers, Conservative and NDP partisans gleefully predicted Trudeau’s imminent implosion.

But another, parallel narrative has also been playing out much more quietly: one in which many voters think that, screaming headlines notwithstanding, Trudeau’s approach to SNC-Lavalin was right all along. It’s a narrative in which the prosecution of SNC-Lavalin is treated as a conspiracy and the great victims of that conspiracy are ordinary small-town workers and the province of Quebec.

A truism of federal politics in Canada: as Quebec goes, so goes the nation. The province is the crucible of Liberal fortunes in the next election, where wins would offset at least some of the expected losses in neighbouring Ontario. And SNC-Lavalin looms large in Quebec, a province where homegrown corporations are jealously guarded and easily slighted—which is why many Quebecers saw SNC-Lavalin’s treatment as Quebec bashing at its worst. One columnist went so far as to suggest the criminal prosecution of SNC-Lavalin was part of a conspiracy (executed by whom, he doesn’t say) to favour the company’s out-of-province competitors. “Who would benefit if not the other large Canadian companies like Toronto-based Aecon?” wrote Jean-Robert Sansfaçon in the French-language Le Devoir. He added: “Seen from the other provincial capitals, Quebec isn’t only a capricious and spoiled province, but above all very corrupt.”

This abject provincialism makes sense only if we recall SNC-Lavalin’s significance in Quebec. Like Bombardier and Couche-Tard, SNC-Lavalin has the weight and heft of a cultural symbol—proof positive to Quebecers that they can succeed on the world stage. The converse holds as well: when US home-renovation giant Lowe’s purchased Quebec-based Rona for $3.2 billion in 2016, it was seen less as a homegrown success story than a shame visited upon the province. “Rona isn’t a business like the others. It is at the heart of Quebec manufacturing, like a ventricle,” wrote Le Journal de Montréal columnist Michel Hébert at the time. To stretch Hébert’s maudlin simile: if Rona was Quebec’s corporate ventricle, then SNC-Lavalin is its lungs that gave rise to Montreal’s Olympic stadium, the Ville-Marie Expressway, and many of the hydroelectric dams in the province’s north.

SNC-Lavalin’s veins run well beyond Quebec’s borders. The company has refurbished two nuclear-generation facilities in Ontario, built a hospital in New Brunswick and the Canada Line in British Columbia, and spearheaded dozens of other projects. SNC-Lavalin is Québécois in spirit but Canadian by design. In fact, a large majority of SNC-Lavalin’s 9,000 Canadian employees live outside of Quebec, and the people of Sarnia, Ontario—where 175 employees work at SNC-Lavalin’s operation—are probably at least as worried about the company’s fate as Quebecers are. These jobs are stable, well-paying exceptions in an area ravaged by the collapse of Ontario’s manufacturing sector—some of the approximately 3,000 SNC-Lavalin jobs in that province. They also complicate the notion that Trudeau was merely concerned with favouring Quebec (the anglophone mirror of Quebec’s narrative of victimization). Making a public display of saving these jobs—though there are unanswered questions about how imperilled they would really be—and indeed, of saving SNC-Lavalin itself, is the kind of brass-tacks political decision that, in the Liberals’ electoral calculus, outweighs Trudeaupian pleasantries about openness and fairness.

Another political truism: beware of partisan histrionics. For all that Andrew Scheer and his Tory colleagues have been relentless in their criticisms of Trudeau on this file, coming to the legal or financial aid of politically important corporations is old, bipartisan hat in this country. Consider that, in 2009, Stephen Harper’s Conservative government lent a total of $13.7 billion to General Motors and Fiat Chrysler as part of a bailout to save the two companies and thousands of Canadian jobs. Last year, the government wrote off $2.6 billion related to its loan to Fiat Chrysler and, about a decade after taxpayer dollars kept it afloat through a protracted economic downturn, GM announced it was closing its headquarters in Oshawa, eliminating about 2,500 jobs. Supporting SNC-Lavalin is a sure bet by comparison: the company is proudly, almost stubbornly, mated to Quebec, and its employees aren’t beholden to the whims of some foreign-owned conglomerate.

Helping SNC-Lavalin avoid criminal prosecution has always been a dubious proposition—even if it turns out Trudeau didn’t violate proper procedure to do so—if only because the company has behaved so poorly in the recent past. Put aside the nearly $48 million in bribes the company allegedly ladled out to Libyan officials between 2001 and 2011 and the roughly $130 million it allegedly defrauded from the Libyan government and other agencies in that country during the same time period. In doing business in Libya, it slavishly aligned itself with Moammar Gadhafi’s institutionally homicidal regime. When I interviewed then SNC-Lavalin CEO Pierre Duhaime about this for Maclean’s in 2011, he defended the company’s relationship with Libya and heaped praise on Saif Gadhafi, Moammar’s son. When I mentioned that Saif had referred to anti-Gadhafi rebels as “rats,” Duhaime shrugged. “When you are in a war you say some things that maybe you wouldn’t repeat later on, and you don’t really believe it,” Duhaime said. That same year, the International Criminal Court charged Saif Gadhafi with two counts of crimes against humanity for his role in the torture and deaths of civilians demonstrating against his father’s regime.

Justin Trudeau doubtless won’t run the same campaign this year as he did in 2015. Boundless energy and heedless optimism are tough sells after the shortfalls, broken promises, and casual hypocrisies that always come with governing. Instead, expect a campaign in which Trudeau represents himself as the least bad of those vying to become prime minister—a man not without faults, sure, but who suffered scandal only to save well-paying Canadian jobs. Trudeau himself said as much in his first major press conference on the issue, in which he notably didn’t apologize. “I’ve spent my entire political career fighting for justice and for people. Social justice. Protecting Canadian jobs,” he said. At least implicitly, the suggestion will be that the competition would be no better.

“Come autumn, there’s a very good chance people will say, ‘What was that thing with SNC-Lavalin, again?'” political scientist Jean-Herman Guay told La Presse in February. “In almost all democracies, the electorate shrugs and makes a choice based on its relative disgust towards each candidate.” It’s a far cry from sunny ways, but come October, Trudeau may yet turn out to have read the electorate correctly.

June 16, 2019: An earlier version of this article stated that, in 2018, General Motors announced it would be closing its headquarters in Oshawa, Ontario, eliminating 2,500 jobs. In fact, the assembly plant in Oshawa is closing. This will eliminate approximately 2,200 jobs. The Walrus regrets the error.