This story was originally published as “How Can Canada’s North Get Off Diesel?” by our friends at The Narwhal. It has been reprinted here with permission.

This story was originally published as “How Can Canada’s North Get Off Diesel?” by our friends at The Narwhal. It has been reprinted here with permission.

It’s an expensive and sad reality that the universal sound of the North isn’t the howling of sled dogs, the mesmerizing joy of throat singing, the squeaking of boots on super-cooled snow. The real sound—the one that’s consistent from Burwash Landing, Yukon, to Pond Inlet, Nunavut—is the clattering rumble of the diesel generators keeping the lights on.

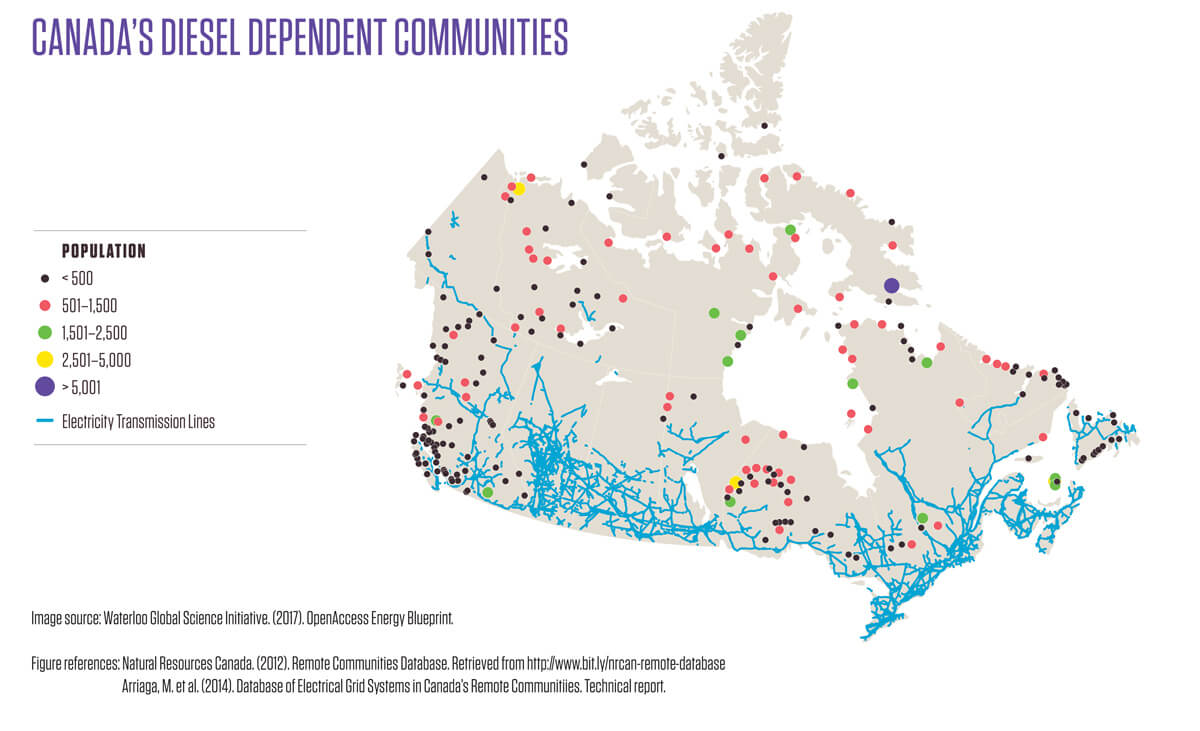

They power every off-grid community in Nunavut, Nunavik, the Northwest Territories, Yukon, and Labrador without exception—and most northern communities are off grid. Diesel generators even keep the lights on in some of the larger centres, such as Iqaluit. Some communities have supplemented diesel with alternatives, such as solar or wind, and others have plans to do so, but the pattern remains: up here, diesel is king.

That means nearly every electron flowing through every lightbulb in Pangnirtung, every BTU of electric heat in Norman Wells, and every Netflix binge in Kuujjuaq has to be shipped in by truck, barge, or plane.

In Paulatuk, Northwest Territories, this October, the annual diesel barge never arrived when extreme fall ice conditions shut down marine traffic through the area. “The community was running out,” recalls Aaron Ruben, who works in the hamlet’s office. The territorial government stepped in to fly 600,000 litres of diesel to the community of 265 people to keep the generators running. Moving that fuel, plus some other supplies, cost $1.75 million over dozens of flights. It was either that or Paulatuk would go dark. “I’m not sure what would have been the next step,” Ruben says.

The next step when the Baffin Island community of Pangnirtung’s diesel generator caught fire in April 2015—with temperatures dropping as low as negative seventeen degrees—was that residents were advised to gather in the school gym to stay warm. Rotating outages lasted days, during which people had just enough power to warm their homes before the power would cut off again. Hospital patients were evacuated to Iqaluit.

The machine that caught fire was among the many outdated diesel generators plaguing the territory. The Qulliq Energy Corporation, which supplies power to Nunavut, says thirteen of its twenty-five generators are already beyond their expected lifespans.

“[Qulliq]’s operating cash flow is…not sufficient to fund the replacement of the older power plants,” the corporation wrote in a report in 2017. Instead of being able to look ahead, the utility is treading water. The $54 million it spends each year on diesel is keeping it from investing in anything new—even new diesel plants. The energy corporation burns 55 million litres of diesel each year to provide power to 38,000 people. The situation has become sufficiently expensive and unsustainable that the federal government has stepped in with funding for a multipronged approach to reduce the North’s dependence on diesel. But it’s a complicated problem, and some of the proposed solutions revert back to old habits.

Map of remote communities in Canada that are dependent on diesel. Source: Waterloo Global Science Initiative.

The Northwest Territories and Yukon have energy grids that include large-scale hydro dams. In Yukon, fast population growth and increased energy demand from electric heating means the utility, Yukon Energy, is scrambling to bring in new power. Its solution? Diesel and liquefied natural gas (LNG) generators. “Maybe ten months of the year now we’re burning LNG,” explains Cody Reaume, energy analyst at the Yukon Conservation Society.

That isn’t much of a solution, according to Craig Scott, executive director of Ecology North, a non-profit that works on issues like climate change, waste reduction, water quality, and food sovereignty. “It’s not much better than burning diesel,” he says, “because there’s huge methane fugitive emissions from fracking and pipelines.” In the Northwest Territories, the cornerstone of the plan to reduce diesel is expanding an already controversial dam and building transmission lines to the diamond mines northeast of Yellowknife.

The reality of the North is this: it’s cold, it’s far from the rest of the country, and its people are spread out over an area that makes up half of Canada. It has the highest cost of living of any part of the country. That cost extends to industry, which pays the same high prices for fuel and groceries as everyone else. That makes it harder to turn a profit, which hinders growth.

These factors conspire to create an extremely energy-intensive society, without a lot of clean or affordable options for electricity, transportation, and heat. This system is a relic of a previous generation, when other options were not available and the majority of the problems that come with diesel were not fully understood.

Diesel generators are spitting out greenhouse gases 24/7, contributing to climate change in a place that is seeing the most dramatic impacts of global warming anywhere on the planet—but they represent a minor contribution to the overall picture. Despite the carbon intensity per person (about twice the national average), the share of Canada’s emissions coming from the North is a tiny fraction of the country’s total; in 2015, all three territories produced 2.3 megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent, just a third of a percentage point of Canada’s 722 megatonnes.

If the oil-and-gas industry were a province of its own, its emissions would outstrip all three territories’ annual emissions by lunchtime on January 4. But greenhouse gases aren’t the only problem with diesel generators.

Environment Canada lists dozens of chemicals known to be released in the burning of diesel, including mercury, formaldehyde, and sulphur dioxide. In Iqaluit alone, diesel is responsible for producing about 290 litres of formaldehyde each year. Diesel exhaust has been unambiguously labelled as a carcinogen by the World Health Organization. “Diesel engine exhaust causes lung cancer in humans,” Christopher Portier wrote in a statement from the UN International Agency for Research on Cancer. “Given the additional health impacts from diesel particulates, exposure to this mixture of chemicals should be reduced worldwide.”

A dizzying patchwork of federal programs is incentivizing people, businesses, and communities to reduce their reliance on diesel. It’s a veritable alphabet soup of acronyms that together represent billions of dollars being thrown at the problem. “Money is starting to flow,” says Dave Lovekin, director of the Pembina Institute’s work on renewables in remote communities. But Lovekin says much of the money is not being deployed in a way that encourages Indigenous participation or solicits local knowledge. “I think one area that is lacking is policies from governments and utilities that support Indigenous inclusion in developing these projects,” he says. “There’s a lot more work needed to work with and advocate and push for better policies that Indigenous communities can participate in.”

Governments are trying to reduce diesel use, in large part due to their desire to lower emissions. But a lot of that diesel never even makes it to the generators; instead, it spills out into the environment from storage tanks or from the trucks, pipelines, and ships that deliver it to the communities. More than 9.1 million litres of diesel has been spilled in the Northwest Territories and Nunavut since the 1970s. More than half of the leaks are from trucks and storage tanks.

In Yukon, those numbers are vague at best. The government knows a lot of diesel has ended up in the environment, but it has a hard time pinning down the exact number of litres due to historically lax reporting. Looking at what records are available, government analysts came up with a total of at least 219,000 litres but say that is definitely an underestimate. “A large amount of the fuel spilled over the last forty years is unreported and, frankly, unknown,” says Cedric Schilder, environmental-protection analyst for the Yukon government. “There was a whole period of time where it was pretty cowboy.”

All the diesel in Yukon needs to be trucked in one load at a time; there are no ports or pipelines connecting the territory to the south. So it’s not surprising that, when it does make it to its destination, diesel produces the most expensive power in Canada.

The average electricity price in Canada is about eleven cents per kilowatt hour. Northwest Territories and Nunavut customers can expect to pay at least three times that. In Kugaaruk, Nunavut, the price for a residential customer is currently $1.12 per kilowatt hour—more than ten times the national average. Those prices are subsidized; the average unsubsidized diesel price across Canada, according to a 2015 engineering journal article, is $1.30 per kilowatt hour.

That’s hamstringing housing agencies, whose budgets are eaten up by the cost of heating. Power and fuel alone cost the Nunavut Housing Corporation about a quarter of its operating budget in 2016/17.

By comparison, the BC public housing corporation spent less than 1 percent of its billion-dollar budget on total utility costs that year. Heating makes up the lion’s share of northern energy use overall and doesn’t require fancy new technology. Scott of Ecology North is unsurprised that this relatively simple change gets less attention than electricity. “The focus is on electricity because it’s easy,” he says. “People can see it.”

But efficiency retrofits to homes and businesses, and switching to wood or wood-pellet stoves, can be as effective as switching energy systems. Without those kinds of retrofits and changes, heating can be expensive enough that some families are forced to do without—and living in a cold home can increase the risk of physical and mental-health problems. According to an editorial from the British Medical Journal, the risk of respiratory illness doubles among kids living in cold homes, while the risk of cardiovascular disease and arthritis grows among adults. Adolescents see a fivefold increase in mental illness. “It’s probably the most pressing issue facing many off-grid communities,” says Nick Mercer, a PhD candidate in geography and environmental management at the University of Waterloo.

All of this—the high cost of electricity, the billowing emissions, the uncertainty of delivery, and the likelihood of spills—is causing even mining companies to think twice about working in the North. Agnico Eagle has two mines near Baker Lake, Nunavut; one, the Meadowbank mine, is in full production while the other, Meliadine, is under construction. Together, the two mines need 130 million litres of diesel fuel per year, at a cost of about a dollar per litre. Eighty million of those litres are burned annually to generate electricity.

It’s a “phenomenal” amount of fuel, the company’s vice president of Nunavut operations, Dominic Girard, told The Narwhal. Agnico Eagle buys nearly two and a half times as much diesel each year than the government of Nunavut, which owns the power corporation. The company is planning to install wind turbines at the Meliadine mine that would cut those needs down. The turbines wouldn’t eliminate the need for diesel entirely—only about 15 percent of it—but savings would still amount to millions of dollars per year.

Other mines have already taken up that challenge. The Diavik and Raglan mines both employ wind power in the North to offset their diesel demands, a model Girard says Agnico is looking at while developing its own project, but with a twist: he wants them to be owned by the local Inuit community. The details of that arrangement haven’t been worked out, but he says it could be mutually beneficial. “We’re not an energy producer—we’re a miner,” he says, adding turbines could be in place by 2021.

The turn to local, Indigenous ownership in energy projects may be just what’s needed to help many remote communities kick diesel once and for all.

The small Arctic hamlet of Old Crow, Yukon, plugged in its first solar panels in 2009. Producing about one-fifth of one home’s energy requirements, or 3.3 kilowatts, it was a modest start.

That modesty is all gone now.

Old Crow has ramped up its commitment to solar and will soon be producing as much as 940 kilowatts—enough to offset 24 percent of its diesel use over the year and completely shut down the generator during much of the summer. In one community, some of the time, there can be quiet. “We burn a lot of fuel up here per capita, and we’re trying to reduce that,” William Josie, director of natural resources for the Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation, told The Narwhal’s Matt Jacques in March 2017. “Anything that affects our community, we want to have control over. That’s our goal with this project, is to have ownership over the facility.”

Similarly, Burwash Landing, Yukon, is building its own $2.4 million wind-turbine installation that will displace one-fifth of its diesel needs.

In Nunavik, a joint venture between the Makivik Corporation and the Fédération des Coopératives du Nouveau-Québec was founded in 2017 to deliver renewables to its communities, where 100 percent of the electricity is currently provided by diesel.

On the doorstep of the oil sands, in Fort Chipewyan, Alberta, a solar project received a $3.3 million provincial grant in early February. The new panels and batteries will increase the community’s solar-electricity production more than sixfold and provide a quarter of its energy. It will be Canada’s biggest solar project in a remote community.

But, in the North, these small-scale, locally owned projects are the exception. Lovekin, of the Pembina Institute, says that may start to change with new policies. “One shift that we’re seeing is government starting to open power up to independent power producers,” he says. Yukon, for example, recently introduced an independent-power-producer policy that includes remote communities. Nunavut is exploring independent power-production options as are other provinces. “Good things are happening,” Lovekin says.

Across the mountains, however, the government is pushing for an expansion of a sixty-year-old facility. The linchpin of the Northwest Territories’ plan to reduce diesel use is expanding the Taltson River dam.

The hydropower station north of Fort Smith has been credibly blamed for inspiring the territorial government in the 1960s to force out the community of Rocher River, which today sits abandoned at the edge of a degraded river. Adding a new power generator, triple the size of the current one, makes up 44 percent of the territory’s planned carbon reductions under the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate.

In Nunavut, large scale also appears to be the favoured approach, but that hasn’t caught on. A two-part hydro plan in the works for Iqaluit since 2005 (with $10 million spent so far) has ground to a halt due to a lack of further funding.

Pamela Gross grew up in and around Cambridge Bay, Nunavut, where she is now the mayor. The hamlet had four small wind turbines installed in 1987, when she was just a child. “I remember them as a kid,” she says. “We had a few of them, then some of them started falling over.”

The four turbines lasted just four years. Another wind turbine was installed in the community a few years later, larger than the first four. It was torn apart in a blizzard just eight years after it was installed.

The realities of extreme weather are slowing progress toward distributed, small-scale power projects everywhere in the North.

Wind power is not alone in facing challenges particular to the climate. Small-scale hydroelectricity, which has been deployed successfully in off-grid communities in BC, runs into problems with ice buildup in frigid northern waters. “If that can be overcome, then microhydro can be feasible for many northern communities,” says Robert Cooke, a technology officer with the Canadian High Arctic Research Station, which has been looking at how best to get distributed energy systems working in the North.

Eight Nunavut communities have been studied for microhydro potential. Costs are high, but in Arviat, for example, a government analysis determined that a $9.8 million microhydro site could more than meet the entire community’s peak energy needs. A plan to replace diesel with a wind-powered microgrid in Iqaluit (including batteries to store energy) recently won the CanInfra Challenge, a competition for infrastructure solutions. Its proponents said a high upfront cost would save $378 million over twenty years, including carbon-tax costs, in that one community alone. The model, they suggested, would be scalable to other remote communities as well.

Ultimately, though, the climate determines what works and what doesn’t. “Not all technology will work at minus forty,” says Cooke.

Just getting the materials to where they’ll be installed is a challenge. When Diavik installed its wind turbines—custom-designed to withstand temperatures up to negative forty degrees—at the Lac de Gras mine, the blades were the largest objects ever to be hauled in along the long ice road connecting Yellowknife to the mine. It took sixty truckloads, using purpose-built trailers, to bring all the materials to the site.

Construction of the turbines at Meliadine and Meadowbank will be planned around the barge season. One year, the foundations will arrive; the next, the turbines themselves. If complications arise—for example, if heavy sea ice or bad weather slows the delivery—the entire project could be set back a year or more.

There have been successes so far despite the headwinds. In Colville Lake, a Northwest Territories hamlet of around 150 people, solar cells work well enough that in the long days of summer—when peak energy demand is lower and the sun is shining brightly—the diesel generator can be switched off entirely now and then. “Community members talk about how important that project had been,” says Cooke—not just for energy savings but for empowerment of a more personal nature.

He says people felt as though they themselves were invested in the success of the project, lending it a greater significance than if the project had been decided upon and followed through solely by outsiders. That approach also makes projects more likely to succeed long term. In remote places, Cooke says, building capacity so that locals can operate and maintain the infrastructure is just as important as building the actual turbines or solar panels.

The cost savings can be significant too; the wind proposal that won the CanInfra Challenge estimated a project in Iqaluit—even at a cost of more than $230 million—would pay itself off within a decade and then the community will save nearly $30 million a year compared to the status quo.

Self-sufficiency has always been part of the northern way of life. Diesel, with its long supply chain and high cost, runs directly contrary to that spirit. That’s where Cooke says alternatives have an edge—and why, with careful planning and a lot of work, they may finally be able to edge out fossil fuels. “On a basic level, if you look at wind energy, solar energy, hydro energy, it’s sustainable,” he adds, “and very much in line with traditional values.”

This story was reprinted with permission from The Narwhal.