Greg was on a mission to make a Black friend, but there weren’t many—any—Black people where he lived.

He made this declaration upon awaking one morning from uneasy dreams (he had been chasing a man), his head hanging off the left side of the bed, his lower back stiff. He could hear his wife typing at her improvised workstation in the closet.

When he repeated his goal, his wife admonished him that he should not approach finding a Black friend like completing an item on a checklist, or collecting a rare Pokémon, or harpooning a white whale.

“It’s a person you’re talking about,” she said. “Not a deer head for the wall.”

“Of course,” he said. (The man had been on foot. Greg had been in his truck.) Why the violent imagery? He liked Black people. He felt sorry for them, especially after those killings in America.

“Tragic,” he said. He rolled out of bed and onto his knees. “Just tragic.”

“Greg, honey, I’m about to enter a meeting.”

“What can we do about it?” He was resurrecting an old conversation.

“Nothing,” she said before realizing that the question, this time, was not rhetorical. “I mean, donate. Every day there’s someone on my Facebook suggesting an organization.”

“I don’t want to give money. I want to do something.”

“Giving money is doing something.” She turned on the ring light. “I’m signing in.”

“I’m not giving money so some bureaucrat can write off his lunch,” he said, though corporate fraud didn’t strike him as something Black people did.

“Then do whatever. Move to Toronto and make all the Black friends you want. Go to Africa.” She put on her professional voice and began greeting her colleagues, and he had to crawl out of the room so he wouldn’t be half-naked in the background.

Not counting the NBA, Greg saw very few—no—Black people on a daily basis. To his knowledge, his wife didn’t have any Black friends either, not even on Facebook. (The man in the dream had been illuminated by Greg’s headlights. The hairs along the back of his neck were like peppercorns.) So, when he beheld a Black man at the Home Depot in the next town, he recognized the significance of the occasion. The man was wearing a navy-blue uniform and standing inside the automatic doors. He was one of those new security guards hired by the store to count capacity limits and urge customers toward the sanitizer.

Greg didn’t know how to talk to the man. Before getting married, he had only ever thought about approaching women. All his lines seemed like pickup lines. He would have to build this friendship in stages.

On the way in, he nodded at the man.

On the way out, holding a shovel, he said, “Bro,” and made a fist in his coat pocket but chickened out of raising it in a fight-the-power, 1968-Olympics way. The Black Panther way. That guy from Black Panther who died. Colon cancer. Tragic, just tragic.

Stage one complete.

“I MADE A BLACK FRIEND,” Greg announced to his wife.

“Check mark,” she said.

He deposited the shovel in the foyer and unlaced his boots.

“What’s his name?”

Before Greg could recall or fabricate a name (the man in the dream had owed him something, had been trying to escape), his wife made a smug, knowing sound.

“I’m not good with names,” he said. He remembered noticing a name tag and a company logo stitched on the Black man’s uniform.

“Labels.” She finger quoted to mock him. “Do you even know my name, Greg?”

“Male friendships aren’t like female friendships,” he said.

His wife scraped the price tag from the handle of the shovel with a fingernail.

“Guys don’t really care about names,” Greg went on. “I call him Bro.”

GREG COULDN’T RISK losing Bro to shift schedules, so he drove back to Home Depot that night, through freezing rain, for stage two.

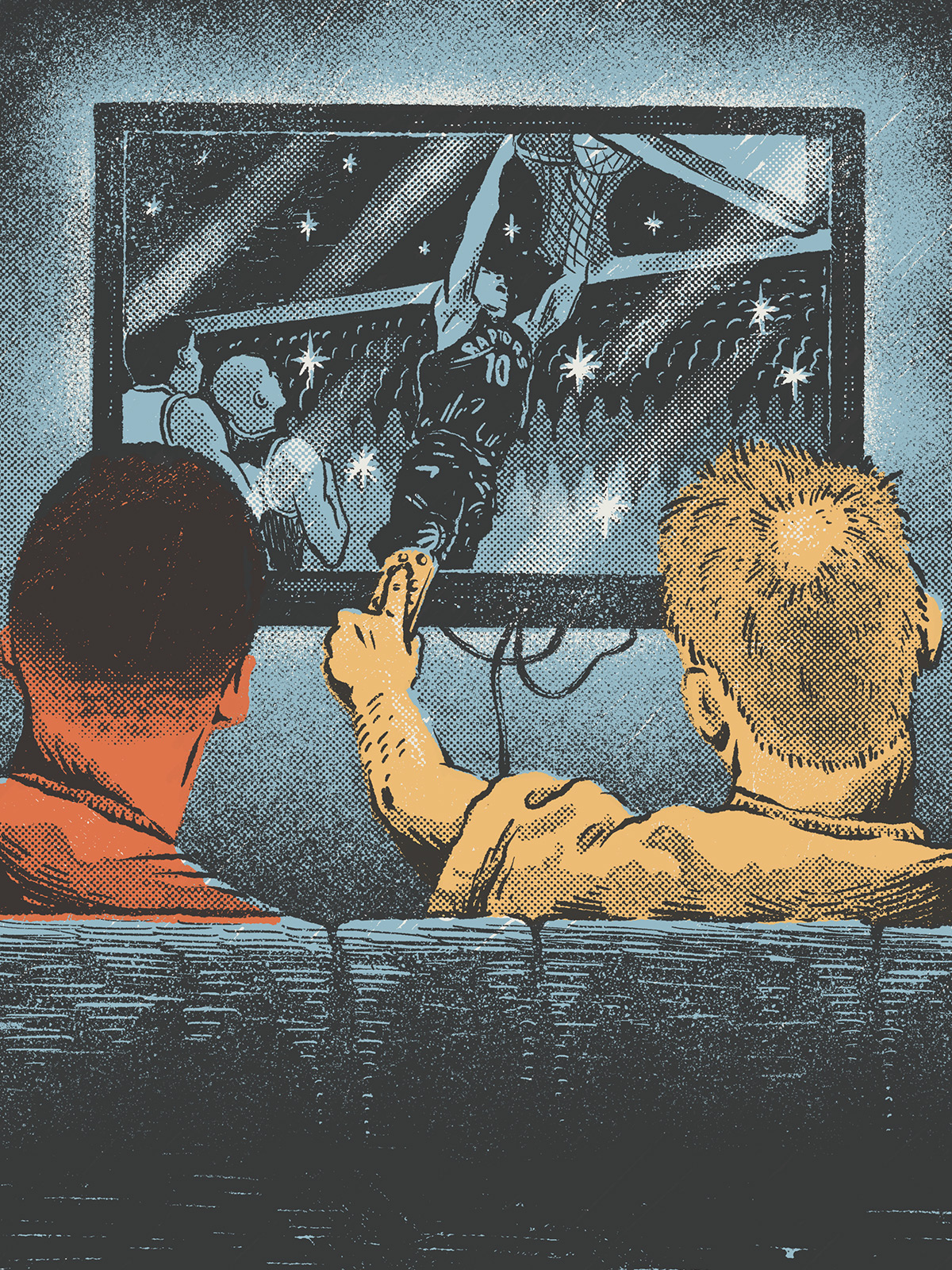

He entered, seemingly absorbed on his phone. “You’re missing a hell of a game,” he said as he approached Bro.

Bro said nothing for a long second, and Greg thought he might have miscalculated the interest Black men have in basketball.

“It’s close,” Greg said, as cool as possible. “But Toronto’s up by three.”

Bro looked around, and then something in him relaxed. (Eventually, Greg had cornered the man in an alley.) “I’m tracking the score right here,” he said, patting the phone in his breast pocket, over his heart, a gesture that seemed patriotic and affectionate.

From that point on, it was a smooth ride through stages three, four, five, and six to besties. Greg told Bro about his sixty-five-inch TV, bet him the Raptors would make the playoffs, invited him over to the house, offered to text his address as a way of getting Bro’s number. Greg didn’t stop talking until a voice overhead said, “Attention shoppers, the store is now closing.”

“We’re vaxed and boosted, so seriously, drop by any time you see my truck in the driveway.”

“Careful what you wish for,” Bro said.

They bumped elbows. Greg grabbed some rock salt and furnace filters on sale and then checked out.

“Keep it real, Bro,” Greg said at the exit, flashing a peace sign.

In his truck, he opened his contacts and saved his new friend’s number under Bro.

Greg stopped parking in the garage. He left his truck in the driveway. (The man had been trapped, Greg’s truck behind him and a chain-link fence in front.) He left the porch light on all night. He agonized over when and how much to text Bro. Bro responded with GIFS and emojis. Black thumbs up. Black happy faces. Greg called twice, but Bro didn’t pick up. “Sorry, was working,” Bro texted.

Greg didn’t lose hope that Bro would accept his invitation one day, but in the meantime, he kept looking for other Black-friend candidates. He followed Black athletes, Black comedians, a Black meteorologist from TV. He sent friend requests to the Black friends of friends. He drew the line at a Black politician he despised, who knotted his scarf in an affected way that irked Greg. He didn’t have to like someone just because they were Black.

But his thoughts kept returning to Bro. When he tried to visualize the kind of Black friend he wanted, he could come up with only minor variations of Bro. Even Bro’s youth didn’t bother him. They could watch TV on the couch with a bowl of chips between them. Greg could dole out fatherly advice about Bro’s ex-girlfriend who had started dating someone else. They could rate women on a scale of one to ten, face and body, as they appeared on screen. They could rewind nude scenes on Netflix.

On another Broless winter evening, while Greg was watching basketball and sinking into a funk, his wife looked at him, exhaled, and said, “You know, I’m part Black.”

It was the fourth quarter. She was on the far end of the couch. He had trouble reading her face in the dark, after a few beers. She folded her reading glasses and placed them on the coffee table.

“How?” he asked. (He remembered thinking, in the dream, that he had to act quickly or the man would jump over the fence.) He couldn’t focus. He muted the TV. “How Black?”

“Small. Fractional,” she said. “How is one to know those things, Greg? How Italian are you?”

“One-eighth,” he said.

“Well, I don’t know. The relative—”

“Ancestor. That’s their preferred word.”

“—is on my mom’s side, but nobody really talks about it.” His wife explained that, before she died of leukemia, her sister had spent a lot of time researching the family lineage so she could pass the information down to her children. Her ancestry DNA test had turned up some Black blood.

“That’s great,” Greg said. A three-pointer caught his eye. “That’s unbelievable.”

The next morning, despite a slight headache, Greg went to work in his wife’s closet office. (He had opened the door, stepped down from the truck, and approached the man.) He could hear her moving around the room, asking no questions despite his very intriguing philosopher’s pose: writing in a notebook with one hand and eating an apple with the other.

“I’ve planned what I’m going to do,” he said.

“I need this space, Greg.” She was groomed from the waist up, inserting an earring into her right ear.

“I’m organizing a protest.”

She let her arms fall to her side.

“A Black Lives Matter protest,” he explained.

“But why?”

“For Black solidarity. Or—What’s the word?—allyship.”

“Yes, but, Greg, protests usually are in response to something.” She put on the patient voice she used when on-boarding new employees. “You protest against something. Something specific. No one got shot recently.”

“No one you know about.”

“There was no verdict on the news.”

“Doesn’t need to be. I’m protesting everything, baby. Slavery, the police, the criminal justice system, Karens, Katrina, the war on drugs, Mandela—”

“You’re protesting Mandela?”

“—all that lost time, how they treated Obama, the banana thing in Italy, that syphilis thing in Tennessee—”

“I don’t think you know what you’re talking about.”

“—blood diamonds, the Congo mines for electric cars—I’m protesting all of it.”

His wife was frowning deeply. “Maybe you should talk to Bro before doing anything.”

“I already messaged him. He’s down.” Greg recalled Bro’s thumbs-up emoji of support. “I told him you were Black. He had no idea.”

“Don’t tell people I’m Black. I’m not Black.”

“You are. It’s nothing to be ashamed about.”

“I’m not!”

Greg wasn’t sure which, Black or ashamed.

“I’m not,” his wife continued, “in any real sense. People don’t become Black just like that.”

“What you’re feeling now is forty-three years of white privilege.” He didn’t intend to sound patronizing. “But that doesn’t mean you can’t claim your heritage.”

“What heritage? Look at me!” She was wearing a blazer and a silk scarf on top, checkered pajama pants and slippers below. “My sister—God bless her soul—did some digging online and suddenly I’m supposed to wear a kente headwrap so you can go around saying you have a Black wife?”

Greg recalled the hair products she used to control frizz in the summer.

“So you can check a census box? So you can legitimize whatever self-righteous idea is your latest passion project?” She was shouting now. “You’re white, Greg! You’re a forty-four-year-old white man! Those things have nothing to do with your life.”

Greg looked down at his protest notes from the morning.

“I mean, they’re important, but . . . ”

“But what?”

“Just but.” She turned on the ring light. “I have a meeting and you’re in my chair. This is my space.”

Greg scheduled the protest for a cloudy Sunday afternoon in front of town hall. But the main entrance was cordoned off for construction, so he had to relocate it to the entrance of the public library.

“Why not protest Huckleberry Finn while you’re at it?” his wife said. As far as he could tell, she was there to atone for her outburst, but Greg hoped the protest would connect her to her inner Blackness.

He snapped a photo of the location and sent it to Bro. (In the dream, the man had looked between Greg and the chain-link fence.)

The protesters comprised four high schoolers and Greg. Nobody had a bullhorn. One student began creating a sign, ripping a sheet out of her notebook and writing the letters BLM in marker, but Greg said, “No words.” As he was outlining the choreography of the protest, he caught his wife looking at the group with her head tilted, as if trying to read vertical text.

“I called the news crews,” Greg said.

“Oh, sweet heavens, no.” His wife pulled a pair of sunglasses out of her bag and walked toward the construction vehicles.

“Keep an eye out for Bro!” he called after her. Then he turned back to the protesters. “Direct all media questions to me.”

The students nodded. The five protesters took their seats on the library steps. They all wore black, as Greg had instructed on Facebook. He distributed the masks he’d bought online—black with a white fist on the front—and the students giggled. According to Greg’s notebook, the protest was of the nonverbal / sit-in / occupy sort. It looked, at first, like performance art. About fifteen minutes in, when the excitement had already worn off, it began to drizzle. A few protesters were sitting with their eyes closed. It looked like Falun Gong meditation. Then, around the half-hour mark, the students started checking their phones, and the protest just looked like a father and his four kids waiting for a minivan.

Greg checked his phone. Rain spattered the screen. (The man had run toward the fence.) No notifications from Bro. No activity on the Facebook page.

After an hour, his wife returned. “Okay, that’s enough. Do any of you kids need a ride?”

“More people will join us,” Greg said.

“Bro is not coming.” She delivered the statement bluntly, an atheist to a believer.

Yet, as they were speaking, the students’ eyes shifted to something in the distance. When Greg looked, he saw a Black man walking toward the group. (Through the fence. The man had run through the fence.) His wife’s mouth hung open.

Greg stood up to greet him.

“Sorry,” the man said. “There was a parade I had to cover.” He looked around, as if trying to determine whether he had missed the protest. “I write for the Trend. Are you Greg?”

“I am.” Greg stretched his lower back, looking weary and mildly heroic, one foot on the sidewalk, one on a step, the slightest lift of his chin.

“Cool, cool. I was expecting a brotha—”

“He’s tied up.”

“Cool, cool.” The man tapped his phone a few times and held it under Greg’s mouth. “So, tell me, Greg: Why are you doing this?”

Greg lay in bed, reading the article to his wife from his phone. (The fence had sliced diamonds through the man’s body as he crossed, yet he emerged intact on the other side.) The article quoted Greg saying “centuries of oppression,” “systemic racism,” “call to action for every citizen.”

“I’m going to send the link to Bro,” he said.

“Oh, Greg, honey. Please don’t.”

He hadn’t heard from Bro in a while. That man worked too much. (And the man had kept running, through a field on the other side, without looking back to see if Greg was still chasing him.)

“I mean, you’ve done enough.” His wife turned away from him. “So much already.”

This story was originally published in Italian by Sotto il Vulcano.