If an English jurist from the middle ages sat in on a modern Canadian criminal trial, he would be shocked by many things—especially the length of the proceedings and the protections offered the accused.

He also would be surprised to learn that the jurors were all strangers to the defendant. When the common law was in its infancy, most ordinary people lived as farmers or labourers in small villages, where one’s vices and virtues were a source of common knowledge and gossip. The jurors who decided one’s guilt or innocence—neighbours, cousins, drinking friends, childhood rivals—were expected to bring their intimate knowledge of your character into the courtroom (such as it was). It was only more recently, with the emergence of large cities, that juries of anonymous strangers could be assembled as a matter of right.

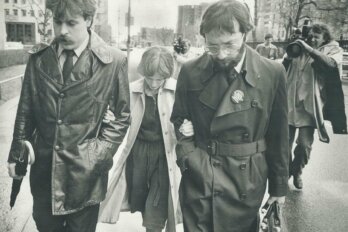

On the afternoon of Saturday, February 2, 2013, police were called to a home on Clancy Drive in Toronto, where they found the body of a dead woman who’d suffered grievous injuries. Eighteen-year-old Mohamed Adam Bharwani was charged with the victim’s murder, and has pled not guilty by reason of insanity. Last month, I was among 120 Torontonians who filed into a courtroom at 361 University Avenue, as candidates to become jurors in a hearing to determine Bharwani’s fitness to stand trial.

The very first questions asked of us by Ontario Superior Court Justice Michael Code all began with the same three words. First came “Do you know me?” then “Do you know Mr. Bharwani?” “Do you know the Crown?” and on through the victim, the defence counsel, and everyone connected with the proceedings. Anyone who answered in the affirmative to any of these questions would have been excused from consideration. But no one did.

My presence in that jury selection pool surprised some of my friends, who assured me there are many ways to get out of jury duty. Lawyers are exempt, for instance. And a few years ago, I was released from selection by showing the sheriff’s office an email from Expedia indicating that I was flying out of town a few days hence. The café owner who serves me my daily breakfast claims that his cousin got out of jury duty by indicating loudly to the courtroom that he was bigoted in regard to the race of the accused. (“They’re prone to that kind of thing!” is what he reportedly said.) Another, more discreet, option would have been for me to get a letter from my boss indicating that my absence would cause undue hardship to my employer (though the consensus on social media suggests that the opposite is true).

I decided to stick it out. If someone is accused of a serious crime, their whole life hangs on the jury’s assessment of his actions. I am not one for earnest civics lectures. But jury duty is one area where I think we all should abide by our obligation to society-at-large, both in letter and spirit.

Before the selection process began, Justice Code showed us a video explaining what jury detail would entail—including the possible financial losses we might suffer from foregone wages. The film also featured scripted testimonials from a series of ordinary working folk, describing how enriching their experience as jurors had been. It seemed corny. But according to Justice Code’s Superior Court benchmate, Justice Melvin Green, jurors almost always take their responsibility very seriously. We have all read stories of mistrials caused by jurors falling asleep. But these examples, he told me, are rare.

The process of actually selecting jurors from among my group began with a lottery. All our names were put in an old-fashioned rotating wooden drum, like the kind they use when awarding gate prizes at a fair. One by one, names were picked out, and the selected individuals would approach Justice Code, whereupon he would ask them to “meet eyes with the accused”—by which he meant Bharwani, a tall, lanky, somewhat dazed-seeming youth who remained standing during the entire proceeding, flanked by two police officers. The man’s stare was completely vacant, which made the exercise seem more awkward than unsettling. (After the day was over, I asked an Ontario judge what the point of this eye-locking ritual was, and he had no idea.)

Justice Code also asked the selected jurors whether there was any reason—medical or otherwise—why they would not be able to serve in the required timeframe. (In our case, it was a two-day hearing. Most trials are much longer.) And it was here that the selection process took an odd turn—because answering this question honestly can require prospective jurors to divulge sensitive personal information in front of a room full of strangers. One woman, for instance, indicated that there was no one available to look after her two young children. A man told the judge that he believed the whole ordeal would make him very anxious, and that when he becomes nervous “he has to go to the bathroom.” Another fellow, who listed his occupation as forklift operator, said he would not be able to concentrate on any kind of courtroom proceeding, because his epilepsy medication causes him to be distracted and out of sorts. “Are there a lot of forklift accidents around your workplace?” the judge deadpanned, getting a huge laugh from all of us.

Some of us stopped laughing abruptly when the accused glanced around the room, bewildered by a joke that he didn’t seem to understand. It dawned on me that it was macabre to be sharing laughs in the shadow of a murder trial.

After having disclosed our occupation and the neighbourhood in Toronto where we live, each of us stood in turn as the Crown and defence counsel pronounced on our desirability as jurors—stating either “content” or “challenge.” For any one juror to be accepted, both lawyers had to declare “content.” The process could not go on forever: each lawyer had only twenty challenges to use. But they were “peremptory,” meaning that the lawyers did not have to explain their reasoning.

I could not help but notice that the defence counsel systematically used his challenges to methodically eliminate the female jurors: By the time the entire Jury had been selected, every one of the twelve individuals was a man, almost all of them thirty- and forty-something visible minorities working in technical professions.

The judge told us that we should not be “offended” if we are challenged—that this does not signify we are bad people. This seemed obvious to me. But I must admit that when I was turned down by the Crown (after being deemed acceptable by the defence), I felt an irrational, momentary sting of rejection.

The truth is, I was hoping to be accepted, so I could see the jury process from the inside. Yet even if I’d been picked, I never would have been able to write about the experience—because once a juror becomes sworn, he can’t divulge any details of the proceedings in which he participates (let alone publish articles about the experience). While one sometimes sees American jurors on CNN, spilling the beans about how they came to their conclusions, Canadian rules are more strict.

Thus my sense of lingering disappointment: For all I know, this will be the closest I ever come to witnessing the deliberations that lie at the very heart of our criminal justice system.