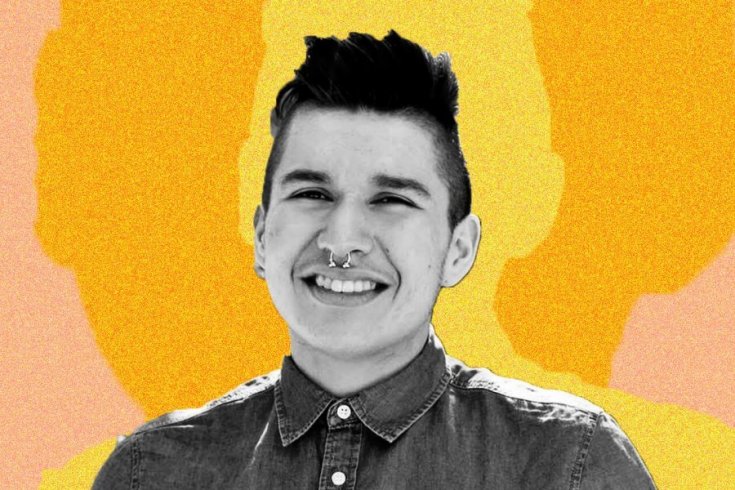

Billy-Ray Belcourt’s first website looks like the kind of DIY project many of us born in the mid-nineties attempted. A badly pixelated banner image features a floral print over which the smiling poet is superimposed: septum-pierced, plaid-shirted, top-button-fastened, and flashing the peace sign. His Twitter presence belies the same unpretentious charm. One post, on the struggle between his desire to write a densely theoretical non-fiction book and the collective expectations of his audience, editors, and publishers, is told using a variation of the “distracted boyfriend” meme—a man gawks over his shoulder, to the disgust of his girlfriend, at a passing woman in a red top.

Belcourt, whose childhood was split between the Driftpile Cree Nation reserve and the tiny nearby hamlet of Joussard in rural Alberta, published some of his earliest poems on this unassuming WordPress site, which he named nakinisowin, the Cree word for resistance (also his moniker on Instagram and OkCupid). It’s hard to know how many took notice back then. But last year, these same poems appeared in his first collection, This Wound is a World (Frontenac House). Now in its fourth reprint, Belcourt’s debut has sold almost two thousand copies and has been requested by university professors across the country. It was named one of CBC’s best poetry books of 2017, and on June 7 has a good chance of making its twenty-three-year-old author the youngest-ever recipient of the $65,000 Griffin Poetry Prize.

That wouldn’t be Belcourt’s only significant achievement. In 2016, he became the second Canadian from a First Nation to win a Rhodes Scholarship—a full ride to Oxford for his master’s degree in women’s studies. The world’s most prestigious academic award was created in 1902 from the will of Cecil Rhodes, a British imperialist whose policies laid the groundwork for apartheid in South Africa. In addition to examining Belcourt’s academic performance and extra-curriculars, the selection committee asked how he planned to reconcile his identity with that of a colonialist like Rhodes. Belcourt replied that maybe it was important the committee select someone was not an archetypal Rhodes Scholar. “I did not succeed in spite of my Indigenousness,” he later wrote. “I succeeded because of my Indigenousness.”

In media interviews, Belcourt strives to frustrate what he calls “vampiric modes of reading that non-native people might take on,” such as voyeurism and fetishism—the desire to see Indigenous suffering played up for dramatic effect. In conversation, he speaks fluidly but answers questions first with long silences during which he considers his words carefully. His phrasing also tends toward abstract sociological theory, and can be difficult to follow.

Key to the success of This Wound is a World, then, is that Belcourt doesn’t write the way he speaks. “There are a lot of poets who take up the call to be opaque or indecipherable,” he says. “Then there are others who nest in simplicity, where it’s more about this raw sense of connectivity.” In his essays, theory wins out. His critical prose has been published widely on topics from the shortcomings of reconciliation to the politics of gay male desire. He has been called a public intellectual, politically necessary, and a genius. But for all his time at Oxford and his impending PhD, Belcourt’s poetry is remarkable not for how it elevates him above his peers, but how it allows him to speak directly to them.

T.S.Eliot’s insistence that, to match the world’s complexity, modern poems “must be difficult” sharpened one of the biggest debates in contemporary poetry. Is poetry better when it prizes obscurity, refuses to give away all of its meaning on the surface, and instead offers layers for multiple readings? For American poet Marianne Moore, the real question was one of good complexity versus bad complexity: that which faithfully reflects the already complicated-enough nature of reality versus that which muddles reality with mystifying language or labyrinthine metaphors. More recently, the poet Kay Ryan—whose own work is no less meaningful for its short, straightforward lines—argued that language itself is already complicated enough. “To use a word is to take a step into a jungle of forking paths,” she said, while “clarity is an ideal to which we can aspire safely.”

Within Canada’s Indigenous literary movement, clear writing has been used to lay bare the realities of life under colonialism for First Nations, Métis, and Inuit people. Maria Campbell’s 1973 autobiography Halfbreed was among the first modern books to do so, and the spare, honest prose with which she detailed the conditions of her life—poverty, addiction, and relentless discrimination—inspired many to do the same. Ten years later, Campbell’s influence could be seen in Beatrice Mosionier’s In Search of April Raintree, a novel about two sisters taken from their parents by Manitoba’s Children’s Aid Society, separated, and raised in foster care. The book—one of the first Belcourt himself can recall having an impact on him—is based on Mosionier’s own experience growing up as a ward of Children’s Aid. In a review for Queen’s Quarterly, Judith Russell wrote: “[Mosionier] sets out to tell a story—her own story—in the plainest available language. Nothing else is needed.”

Too often, readers’ first reactions to texts like Halfbreed, In Search of April Raintree, or This Wound is a World have been to turn away or, worse, to insist—in the vein of Senator Lynn Beyak or a too-large number of conservative pundits—that the Indigenous experience in Canada can’t have been all bad. This kind of historical revisionism makes it all the more important for writers like Belcourt to set down their experiences in straightforward, unmistakable statements.

At his most political, Belcourt’s directness can border on the acerbic. His poem “God’s River” stems from Health Canada’s response to the 2009 swine flu pandemic, which hit Indigenous communities in remote northern Manitoba hardest. Along with a shipment of face masks and hand sanitizer came dozens of body bags, a gesture then Grand Chief David Harper equated to sending body bags to soldiers in Afghanistan. “Don’t send us body bags,” he said. “Help us organize. Send us medicine.” To this Belcourt responds: “remind them / that canada is / four hundred / afghanistans / —call it ‘colonialism.’”

“If Our Bodies Could Rust, We Would Be Falling Apart” responds to the July 2017 death of Barbara Kentner, who was hit in the stomach by a trailer hitch thrown from a passing car. After Kentner was hit, Brayden Bushby, her alleged assailant, reportedly exclaimed: “Oh, I got one!”—but Thunder Bay police nevertheless refused to investigate the attack as a hate crime because there “were no comments which made any reference to race or ethnicity.” Belcourt writes: “it is basic syntax. one is the object and she is at the mercy of the i.”

But while poetry as a form of protest is an important facet of Belcourt’s work, only a handful of the thirty-seven poems in his debut take on overt political subjects. More often, Belcourt’s preoccupation is with love. “It is very easy to fall into the ruts of agony and rage when writing about the ongoingness of oppression,” he says. “But I see fit to always return to love, because I think there’s more room for one another in that style of writing.”

There are two kinds of love in This Wound is a World. The first is decolonial love, which Belcourt defines, citing Leanne Betasamosake Simpson’s Islands of Decolonial Love, as “the ways in which we try to undo how colonialism operates at the level of emotion.” In practice, this can manifest in something as radical as loving oneself in a world filled with messages that one is undeserving. The second kind of love is composed of mainstream (mis)conceptions about romance and intimacy, particularly within queer hook-up culture. This is the love of poems like “There is No Beautiful Left,” whose form echoes that of a two-a.m. Grindr chat, and “Love and Heartbreak are Fuck Buddies,” which references one character’s tryst with a parkade security guard who jokes, locking the door behind him, “Don’t worry, I’m not going to kill you or anything.”

Not all Indigenous poets have chosen to be so plainspoken. If Belcourt wins the Griffin Prize this week, he will be the third consecutive Indigenous Canadian to do so. Jordan Abel’s Injun, last year’s winner, is a book-length found poem built from the public-domain contents of ninety-one Western pulp novels, which Abel curated into one massive document after searching for the book’s eponymous keyword. The poems are harrowing for their background as blatantly racist real-world texts, but can be difficult to comprehend in isolation. Whatever personality can be found in Injun is embodied by the conceptual project, not delivered by the poet’s voice. As readers, we never get to know Abel through his work the way we do Belcourt.

And for Belcourt, that kind of connection is everything. Before it met mainstream acclaim and landed on the Griffin shortlist, This Wound is a World’s goal was to resonate with young, queer Indigenous readers—to offer them a rare opportunity to see themselves reflected in literature. Based on the online response he’s received, Belcourt has succeeded. He has excelled in literary and academic establishments without compromising his work as an activist, his identity as nakinisowin, or the piercing clarity with which he writes his experience. But as much as these successes hinge on and can emphasize difference—queerness, elite scholarship, Indigeneity—Belcourt’s poems are most effective for how they allow readers to feel, for fleeting moments, that their emotional lives are the same as his. “I see poetry as a place to pit language against self,” he says. “To give up on convention, and give oneself up.”

June 6, 2018: An earlier version of this story stated that Belcourt was the second Indigenous Canadian to win a Rhodes scholarship. In fact, he was the second Canadian from a First Nation to win the award. The story also mistakenly stated that Belcourt would be the second consecutive Indigenous Canadian to win the Griffin Prize. In fact, he would be the third. The Walrus regrets the errors.