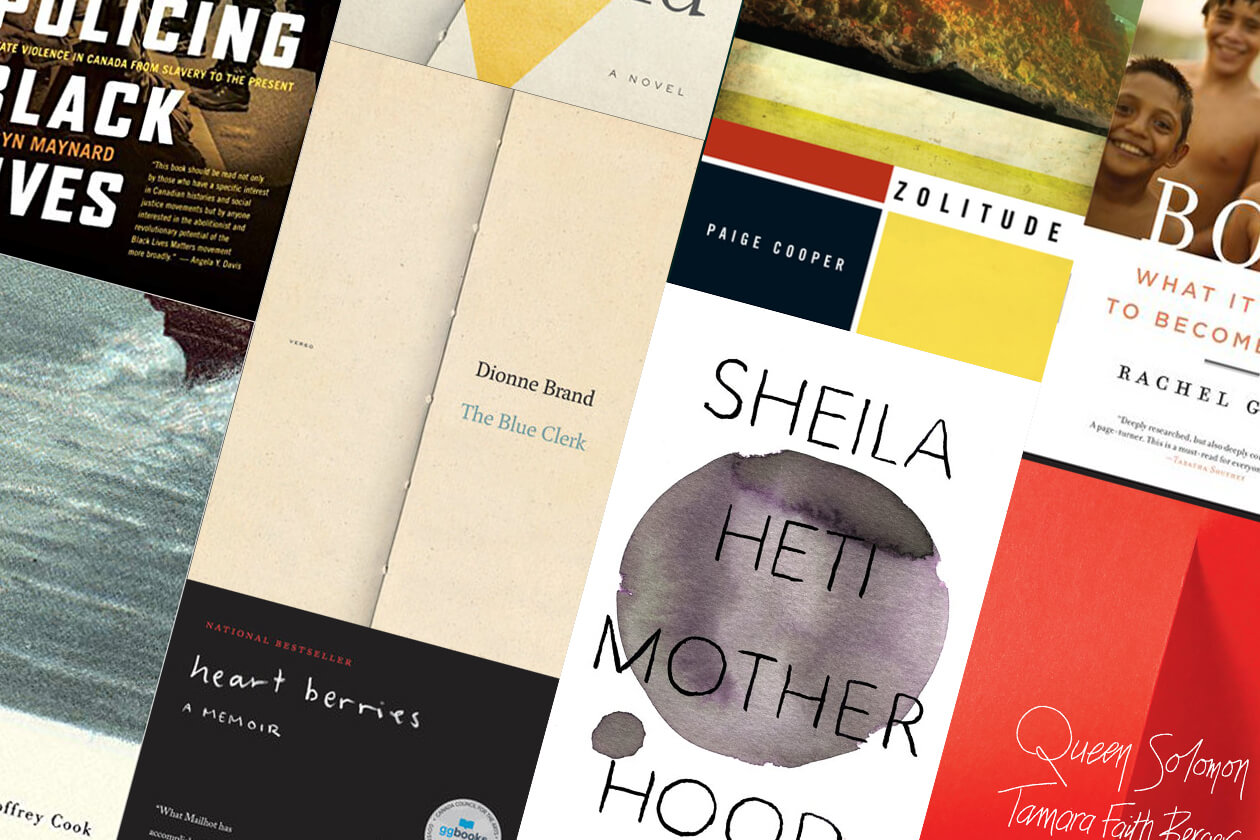

Heart Berries by Terese Marie Mailhot

Heart Berries is a memoir about an Indigenous single mother who loses custody of her first child as she is giving birth to a new one. Mailhot packs up her bags and baby and decides to become a writer. She explores her own imperfections and desires and abuse in a writing style that is so distinct and so personal. She turns her life into a fragile and omnipotent myth. I adore the vicious way she approaches her own lust. I also love how she puts herself first and how raw and new that seems in a female narrator, especially a mother. I swallowed this book whole.

—Heather O’Neill is the author of three novels. Her latest is The Lonely Hearts Hotel.

The Blue Clerk by Dionne Brand

An “ars poetica” and instant modern classic, The Blue Clerk offers an original philosophy of writing by staging the creative act as “a negotiation between what is said and what is unsaid, between what is written and what is withheld,” between the right-hand page (the recto) and the left-hand page (the verso), and between the identities of “the author” and “the clerk.” Through drama and prose poetry, Dionne Brand tackles censorship, the archive, the agency of language, and the ideologies of authorship. Pointedly, the book is about creativity in the aftermath of slavery and colonialism, about life within the necrotic scripts of history. The Blue Clerk is beautiful—physically beautiful—in the nakedness of its stitched blue spine. But the book is beautiful, most substantially, in its sumptuous and incendiary prose, in its fierce challenge to the illusions of literature, and in its manifest belief in the act of writing.

—David Chariandy is the author of Brother.

Zolitude by Paige Cooper

Paige Cooper’s Zolitude: there are tropical forests; strange, shackled beasts in the underbrush; and a febrile, phosphorescent imagination with wastrels and rock divas on speed dial. Every sentence in this story collection is a spring-loaded trap covered in leafy camouflage. Here’s an example of such a sentence, picked arbitrarily by closing my eyes and putting my fingertip on a page somewhere in the middle: “As I sprint I’m afraid that the rockslide is going to fill the canyon, yet I am sprinting towards it.” This sentence opens like butterfly wings that are bark brown on the outside and flamboyant orange on the inside. We don’t expect the revelation. The narrator is heading toward the destruction at a sprint. The sentence is full of suspense.

Well, obviously I can’t stop there, because that sentence is a cliffhanger, with boulders tumbling down an actual cliff. So, further down the page: “The baby is shrieking. The stroller rests, half-submerged in icy water, plastic windshield intact.” I love that comma after rests. A reprieve from the shrieking, balance. But, no, the stroller is sinking, and then another comma, another reprieve, the windshield intact. The word intact, in this instance, alive with impermanence and fragility. All the clauses provoking opposite reactions, packed in the one sentence. As with the tense, vibrant sentences of writers Mark Anthony Jarman and Elise Levine, each line of Zolitude is neon. The atmosphere in these stories crackles and clings for a long time after reading. Or devouring. I love these stories.

—Lisa Moore’s short-story collection Something for Everyone was released in 2018.

Theory by Dionne Brand

Dionne Brand’s Theory is a masterpiece. The novel’s speaker, a PhD student who is perhaps a genius, is working on extensive iterations of her dissertation. The project is to be her life’s work. The narrator is also in pursuit of many kinds of love. Theory and action—how to know, persuade, or mourn and how to be alone and also with love—make their arguments throughout the novel, building and dismantling the speaker’s life. I love this book. It holds the world up to be examined in an ever-shifting light. In a year of astonishing fiction—Esi Edugyan’s Washington Black, Lisa Moore’s Something for Everyone, Catherine Leroux’s Madame Victoria, Rawi Hage’s Beirut Hellfire Society—Theory stands out as a book for the ages.

—Madeleine Thien won the Governor General’s Literary Award for Fiction and the Scotiabank Giller Prize for 2016’s Do Not Say We Have Nothing.

Queen Solomon by Tamara Faith Berger

One struggles to describe Tamara Faith Berger’s latest novel with anything but clichés: “a novel of ideas,” maybe, or “an important book” by “a writer at the height of her powers.” Clichés being, of course, the linguistic life rafts for which we grasp when something upends everything we think we know. Yet none of these rote phrases captures the experience of reading this massively complex book or the sheer scope of what it accomplishes in its mere 170 pages. Queen Solomon is at once a scathing, and occasionally hilarious, parody of the coming-of-age family drama and one of those works of art that seems to take on everything: race, class, sexuality, trauma, imperialism, you name it. The story is this: Barbra, an Ethiopian Jew relocated to Israel under the repatriations of Operation Solomon, is adopted in turn by a Toronto family, and she then initiates our sixteen-year-old narrator into all manner of awakenings, some more consensual than others. This was the book of the year for me—not just from Canada but anywhere. But be warned: it is not easy going. You will be challenged. You might also be changed.

—Pasha Malla’s most recent novel is Fugue States.

Motherhood by Sheila Heti

Sheila Heti’s novel treats a woman’s decision about whether to become a mother as an intellectual question. Motherhood doesn’t provide an answer—it isn’t that kind of book. Instead, the satisfaction lies in the debate the narrator has with herself, with friends, and, occasionally, with the I Ching–style coins that she consults to cross-examine her thoughts. As with Heti’s breakout autofiction novel How Should A Person Be?, the boundary between author and narrator is blurry in Motherhood, and even more so in the audiobook version. The voice is intimate and true, and how could it not be? The book is narrated by Heti herself.

—Emily Urquhart is the author of Beyond the Pale.

Zolitude by Paige Cooper

Zolitude teems with ideas, detail, and beautiful sentences in stories that manage to be profound without sacrificing entertainment. From the masterful time jumping in “Slave Craton” to the violent lightness of the mail-bomb popstar world of “Ryan & Irene, Irene & Ryan,” Paige Cooper shows through her careful prose and wild inventiveness that she is, as Mike Patton would say, the Real Thing.

—Naben Ruthnum is the author of Find You in the Dark (published as Nathan Ripley) and Curry.

Boys by Rachel Giese

For the last few years—or, frankly, for my entire life—there’s been a lot of talk about toxic masculinity, how it hurts women (and how!), and what we’re supposed to do about it. Despite those discussions, it’s rare to find an educated and empathetic nonfiction book that grapples with the damaging lessons that boys are taught about how to be “a man.” Boys by Rachel Giese does just that. It’s written with incisive reporting and personal experience that looks at every facet of how boys are taught to be in the world and how we can start to dismantle those expectations for everyone’s betterment. Plus, a book about gender norms that also looks at sexual orientation and race? Imagine! If you care about women and feminism, you have to care about boys and how they’re raised.

—Scaachi Koul is the author of One Day We’ll All Be Dead and None of This Will Matter.

Policing Black Lives by Robyn Maynard

Robyn Maynard’s Policing Black Lives is one of the most necessary correctives to Canada’s historical narrative to emerge in the last several years. The myth of Canadian support for Black women and men against the backdrop of American slavery has been perpetuated publicly and politically for many years, but Maynard delves far back into pre-Confederation history to highlight how colonial policy and the international bondage market conspired to cement the perception of Black people as inferior in the eyes of Canadians, resulting in centuries of structural bias built into our laws, policing, and public perception, all of which still persists today. In describing Canada’s systemic imbalances, Maynard lays out a methodical and meticulously constructed case that contextualizes foundational works from Afua Cooper, Dionne Brand, and numerous historians for a generation of readers coming of age in the Black Lives Matter era.

—Dimitri Nasrallah is the author of The Bleeds.

Afterwords by Geoffrey Cook

Fourteen years after his impressive debut, Postscript, Quebec poet Geoffrey Cook returns with Afterwords. “Afterwords” are literally “words after”: the book is a collection of Cook’s note-perfect English interpretations of works by four great German poets who wrote between the 1770s and the 1950s. The trick here is that the poems are not arranged by author but in a thematic sequence that tells a strikingly contemporary story of emigration, loss, passion, and discovery. Thus, the very different exiles that Goethe, Heine, Rilke, and Brecht underwent all become facets of one larger human journey. Cook moves from Heine’s leeches to Brecht’s fishing gear, then—in one memorable page turn—to Rilke’s migrant ship and Goethe’s moon glimmering on the sea. Ships and water abound in Afterwords; Cook’s Nova Scotia background and the current migrant crisis no doubt play a part. While Goethe takes a gondola to his assignations “on life’s grand canal,” and Brecht describes a watery departure: “As the pale cadaver decomposed in water, / it happened that, piecemeal, God forgot her: / first her face, then her hands, and last her hair.” In other poems, bodies do all the things bodies do; joyous, frank, unflinching. (The Germans really are better at taking their clothes off.) But most of all, it is Cook’s deft, inventive touch and colloquial verve that make these great poems speak to us. To quote his Brecht: “As the kids say, it’s all good.”

—Richard Sanger’s Dark Woods was one of the New York Times’s ten best poetry books of 2018. He lives in Toronto.