On a bright Sunday morning last year in Toronto’s suburban east end, I enter one of those low-slung church buildings of red brick and dark wood built in the 1960s for neighbourhood families—the kind equipped with a wheelchair ramp and abutted by a broad parking lot. Inside, there are about seventy people, not all of whom, it turns out, are locals. Doug, seated behind me, says he’s travelled halfway across the city to be here. Before I can ask, he explains that he spent most of his life avoiding churches—rebelling against his mother’s insistence that he needed to be “saved.” But when he reached the age of sixty, Doug found that his life was missing something. He’s come here in search of it, every Sunday for the past three years.

A middle-aged man in a white shirt and jeans touches the keys of a grand piano, though the song he plays can’t really be called a hymn. I recognize it from my childhood, when I attended church regularly. It’s called “The Church’s One Foundation.” But the lyrics projected onto the screen before us—“if truth still guides our journey, where does it lead from here”—are nothing like those I remember from the original hymn, composed 150 years ago by Samuel Wesley, nephew of the founder of Methodism. Back then, it went, “The church’s one foundation is Jesus Christ her Lord / She is His new creation by water and the Word / From heaven He came and sought her to be His holy bride.” Nothing could be further from what the West Hill United Church preaches today. Here, there’s a sermon on the power of forgiveness, followed by inspiring readings and songs—but there are no prayers, no liturgical readings, no mentions of the Bible or Jesus or God. The “quote of the week” is from Mark Twain. The service itself is referred to as a “Sunday gathering.” Jesus Christ is not the one foundation of this church.

West Hill is what those who were skeptical about the United Church of Canada feared would happen, back when the institution was established in 1925. The new church had no creed, they said; it was more interested in political activism and social reform than in the Christian faith and the spiritual lives of worshippers. By allowing people to believe in anything, it would ultimately come to believe in nothing.

For almost twenty years, West Hill has been the preserve of the Reverend Gretta Vosper (although she says she doesn’t like to use that title: “I don’t think I should be revered more than anyone else”). Born in Kingston, Ontario, and a graduate of the theology school at Queen’s University, Vosper was ordained as a minister in 1993 and took up her current post four years later. In 2001, she revealed to her congregation what she had always believed—that all religions were mere human constructions, best guesses at the nature of God and the meaning of life. She said that she didn’t believe in a God that answered prayers, or that the Bible was the word of God. She did not accept the divinity of Jesus or presume to know what happens after death. Yet, in spite of these revelations, Vosper’s congregation has stuck by her.

Vosper has become a lightning rod within the broader church community. The denomination’s official magazine, The United Church Observer, has discovered that any story by or about her is guaranteed to garner a torrent of responses. She made her first appearance in the publication in 2005, when she was profiled in an article called “Believing Outside the Box.” The Observer published thirty-three letters to the editor in its wake. Reactions ranged from the vitriolic (“what she calls living outside the box,” one reader opined, “is actually living with Satan”) to the unflinchingly supportive (“it is thinkers like Vosper,” another wrote, “who offer hope for those who are turned away by the conflict between their rational beliefs and the thinking implicit in the hymns, Scripture and creeds of the established church”).

Her notoriety is hardly surprising, given how outspoken she has been. Vosper contends that many clergy in the United Church (as well as those of other denominations) think like her but lack the courage to say so aloud, to level with their own congregations as she has. In her 2008 book, With or without God, she describes herself as “a minister who has moved from the centre of liberal Christian thought to the bleeding edge of Christianity, struck by the complacency with which I had accepted the liberal framework and shamed by it as well.” It is not an apology, but a clarion call. Vosper believes that things can and should change, and that makes her both a thorn in the church’s side and an embodiment of its possible future—a future in which those who don’t believe in God can still congregate in a sort of spiritual community.

Even the most progressive Christian denominations are ultimately based on tradition. Revolutionary views such as Vosper’s can scarcely go unpunished. Many within the church would like to see her gone. In 2005, a motion to hold a committee to review Vosper’s beliefs was brought to her presbytery (the roughly 3,000 congregations of the United Church are organized into eighty-six presbyteries and thirteen conferences, all of which are overseen by a general council that’s elected every three years). The motion failed to get any traction, and a modern-day heresy trial was averted. But in the spring of 2015, a much more serious challenge appeared: the Toronto conference (the one to which Vosper answers) ordered a “review of the effectiveness” of her ministry.

This all comes as the church finds itself engaged in an existential struggle. Last year, it celebrated its ninetieth birthday. But for decades, more important numbers have been falling: in 2013, for example, it lost fifty-nine churches, more than one per week. In rural areas and small towns, forlorn church buildings stand boarded up; in Canada’s big cities, downtown streets feature old churches that have been converted into condos. Now, many wonder whether the institution will live to see its hundredth birthday—and whether Canadians will even care.

Of course, other mainline denominations, such as the Anglican and Presbyterian churches, have their own problems with declining attendance. But the United Church merits special attention if for no other reason than that it has always been seen as different. Established through a union of Presbyterians, Methodists, and Congregationalists, the United Church was never meant to be like the others. It was to be Canada’s national church—not national with a capital N, like the Church of England, but nevertheless created by an act of Parliament, a made-in-Canada church with a made-in-Canada vision of inclusivity.

Its ambitions were huge. In her 2014 book, A Church with the Soul of a Nation, theology professor Phyllis D. Airhart writes that the church was supposed to bring unity to communities where people would not only worship together but also work toward social betterment. As its own propaganda declared, “By breaking down the barriers of provincialism and sectionalism within itself, the United Church will stand as a symbol of national unity and it will be the task of the United Church, so far as lies within its power, to create and maintain a United Canada.” The early twentieth century, Airhart observes in a 2015 Observer article, “was a time when most Canadians still assumed the mutually beneficial relationship among religion, politics and culture associated with ‘Christendom.’” According to the 1931 census—taken six years after the United Church was established—the denomination counted 2 million worshippers, in a country of just 10 million people.

Those who had opposed the church’s formation, according to Airhart, disparaged the institution as a “creedless church that was little more than a political club.” But by 1965, it had been labelled by the eminent sociologist John Porter “as Canadian as the maple leaf and the beaver.” For decades, politicians were happy to hear the church’s take on any issue: the prime minister was happy to pick up the phone when an editor from the Observer rang. As an institution, as well as through its individual adherents (such as Lester B. Pearson, Nellie McClung, Joseph E. Atkinson, and Stanley Knowles), the church played a substantial role in forming the country’s public agenda. In the grand scope of Canadian history, the collapse of the church—or even its decline—is, therefore, something profound. Yet that’s what is happening, according to Airhart. “For better or worse, the United Church’s ‘glory days’ are behind it,” she writes. “Most people assume its influence will continue to diminish as Canada becomes more religiously plural.”

For years, church report after church report has told a troubling story: there are fewer people in the pews and, indeed, fewer pews. By 2013, with the country’s population at 35 million, the United Church recorded an active membership of fewer than 500,000. Its membership amounted to less than 2 percent of Canada’s population—down from 20 percent in the 1930s. And its ministers are getting older. The average minister in 2011 was fifty-six, and only 22 percent of ministers were under fifty. “It would not be an overstatement to say the membership is in free fall,” says David Wilson, editor of the Observer.

The church’s finances have reflected its declining membership. In 2007, the church laid off twenty people (about 10 percent of its staff) at its Toronto headquarters, closed its audio-visual studio (which had been in operation since the 1950s), and lopped $1.8 million from its global and domestic grants. In 2010, the church cut $9 million from its three-year national budget, reducing grants for a number of theological colleges. In 2013, the general council cut its budget by millions, eliminating jobs and reducing grants to Canadian ministries and overseas partners. Last year, it agreed to cut $11 million from its current budget by 2018.

Since the days when the so-called social gospel informed the work of the minister James Shaver Woodsworth, both at his mission in Winnipeg and in his leadership of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (the precursor to today’s NDP), progressive Christians have tried to achieve social good in their churches and in the halls of government. David MacDonald and Bill Blaikie are both United Church ministers who went into politics. MacDonald was elected as a Progressive Conservative for a riding in Prince Edward Island in 1965, while Blaikie took a Winnipeg riding for the NDP in 1979. MacDonald served in Joe Clark’s cabinet (though he would later split with the Conservatives and join the NDP), while Blaikie remained in Parliament until 2008; today, he is an adjunct professor of theology at the University of Winnipeg.

The stories MacDonald tells about making sure United Church delegations had seats at parliamentary committee hearings seem old-fashioned today, given the church’s waning influence. But, years ago, staffers from its Toronto headquarters made regular visits to Parliament Hill to weigh in on issues such as nuclear disarmament, international development, and social justice. As recently as 2005, MacDonald—by then out of politics but still central to negotiations on residential schools—flew to New Brunswick, where he and church officials spent a morning with then Indian affairs minister Andy Scott, discussing how the churches and the government could handle reparations for residential-school survivors.

Blaikie believes that the last time mainline churches had a real impact on policy was much earlier, in the late 1970s, when they sided with Indigenous protestors to halt the construction of a gas pipeline along the Mackenzie River valley, and later demanded that Aboriginal rights be entrenched in the Constitution Act of 1982. After that, Blaikie says, mainline churches lost their voice in the progressive movement as religion came to be viewed as the province of evangelicalism and conservative politics. “On issues like abortion, gay marriage, and medically assisted suicide, there was a new convergence between Catholic and evangelical churches,” he says. In Canada, through ten years of Stephen Harper, mainline churches exerted no influence. In 2011, an executive minister of the church protested changes to the Canadian Wheat Board; the following year, the church’s moderator (that is, its leader) called the federal government’s approach to climate change a “huge disappointment.” Did anybody—particularly the government—care? Harper might have attended a United Church youth group as a teenager in suburban Toronto, but as prime minister, he was not going to be another Pearson.

The social issues in which the United Church has invested its energy and credibility include First Nations and gay rights. In its heyday, the church operated thirteen of Canada’s residential schools. But in 1998, it apologized for its involvement in residential schools, a decade before the government offered its own apology. The church was among those leading the movement to accept liability, to provide compensation, and to seek truth and reconciliation. Hoping to secure better relations with Aboriginal peoples in the future, it created the All Native Circle Conference in 1988 and financed theological training and healing centres across Canada.

In 1936, the United Church became the first mainline denomination to ordain women. But its proposal, fifty years later, to do the same for gay people proved much more divisive. The church hierarchy pushed ahead, affirming such ordination as official policy in 1988. There was not nearly as much resistance when it supported the use of the word marriage for same-sex unions in 2003, calling upon Parliament to use the language in its pending legislation (which it did). In 2012, almost without notice, the church elected an openly gay man, the Reverend Gary Paterson, as its forty-first moderator; in 2015, it elected a gay woman, the Reverend Jordan Cantwell, as its forty-second.

The church has not wavered on these stances. It withstood substantial membership losses over its gay-ordination policy. On the subject of Palestine—to which the church has long been sympathetic—it took serious heat from supporters of Israel, including, most notably, the unabashedly pro-Israel Harper government. In 2009, the Canadian International Development Agency cut millions in funding to Kairos, a social-justice organization supported by eleven churches and religious groups but seen largely as a creature of the United Church. The group’s vocal support of the Palestinian cause led Jason Kenney, then the immigration minister, to tell an audience in Jerusalem that the cuts were part of an effort to combat anti-Semitism (despite the fact that Kairos supports Israel’s right to exist). Three years later, Conservative senator Nicole Eaton suggested in an interview on CBC Radio’s As It Happens that the church butt out of the Israel–Palestine debate and concentrate on saving souls—just weeks before the church was set t0 vote on a proposed boycott of Israeli goods. Eaton, who at the time was conducting a Senate inquiry into the foreign funding of Canadian environmental non-profits, accused the church of doing political work and overstepping its bounds as a charity. In a boon for conspiracy theorists, the Canada Revenue Agency soon after came knocking to audit the church.

David Wilson joined The United Church Observer as a junior reporter in 1987 and has been editor and publisher since 2006. The magazine, Wilson delights in pointing out, is the second-oldest continually published periodical in the English-speaking world (surpassed only by The Spectator, of London). The Observer was founded by the Methodist Egerton Ryerson as the Christian Guardian in 1829. Its circulation is now 40,000, but as recently as the 1980s, it was about 100,000. True, most newspapers and magazines have seen a precipitous decline in circulation. But Wilson says the Observer has lost many of its subscribers via acts of protest. “The move to ordain openly gay and lesbian ministers was hugely divisive,” Wilson says, “and one of the ways people found to voice their displeasure was through cancelling their subscriptions. We were the piece of the United Church that came into people’s mailboxes, and they slammed the door on us.” Readership losses since then have largely been the result of church members getting old and dying off. “Death and blindness are the two biggest ways we lose subscribers,” Wilson quips.

From his editor’s perch, Wilson has watched the church’s leadership grapple with the realities of its shrinking base. He’s not impressed. “Up until recently, there has been a reluctance in the upper echelons to face the decline head-on,” he says. At the 2015 general council meeting in Newfoundland and Labrador, for example, the council voted to restructure itself to save money—but Wilson saw the move as a bureaucratic gesture that would have no real effect. “I don’t know how it will all shake out,” he says. “I don’t know how the church or any other institution can face these systemic challenges, the biggest being an aging membership and virtually no younger generation appearing on the horizon.”

Every once in a while, the church tries to reinvent itself. In 2006, it started an initiative called Emerging Spirit, which attempted to “raise awareness and recognition of the values and beliefs of the United Church of Canada among thirty- to forty-five-year-olds”—mainly by creating an elaborate online spiritual chat room. The church put $10.5 million toward the initiative and its bold advertising campaign, which included a Jesus bobble-head doll and a same-sex wedding cake. Emerging Spirit ended after three years, with no one quite sure what it had achieved.

The United Church is a big tent; there is no shortage of diagnoses of what’s wrong with it (or of people who would claim there’s nothing wrong with it) and no shortage of prognoses about its future. Of course, the Roman Catholic Church is a big tent, too, but it has a well-established creed to guide it and the pope and his bishops to keep it on course. The relatively creedless United Church has been left instead to drift whither it will—often, it seems, in all directions at once. “We are complex,” wrote the Observer’s then-editor Muriel Duncan in a 2005 issue. “We’re a varied collection of Christians, our stance is apt to be the minority among the nation’s denominations, and at a superficial glance, it may appear a secular philosophy rather than radical Christianity.”

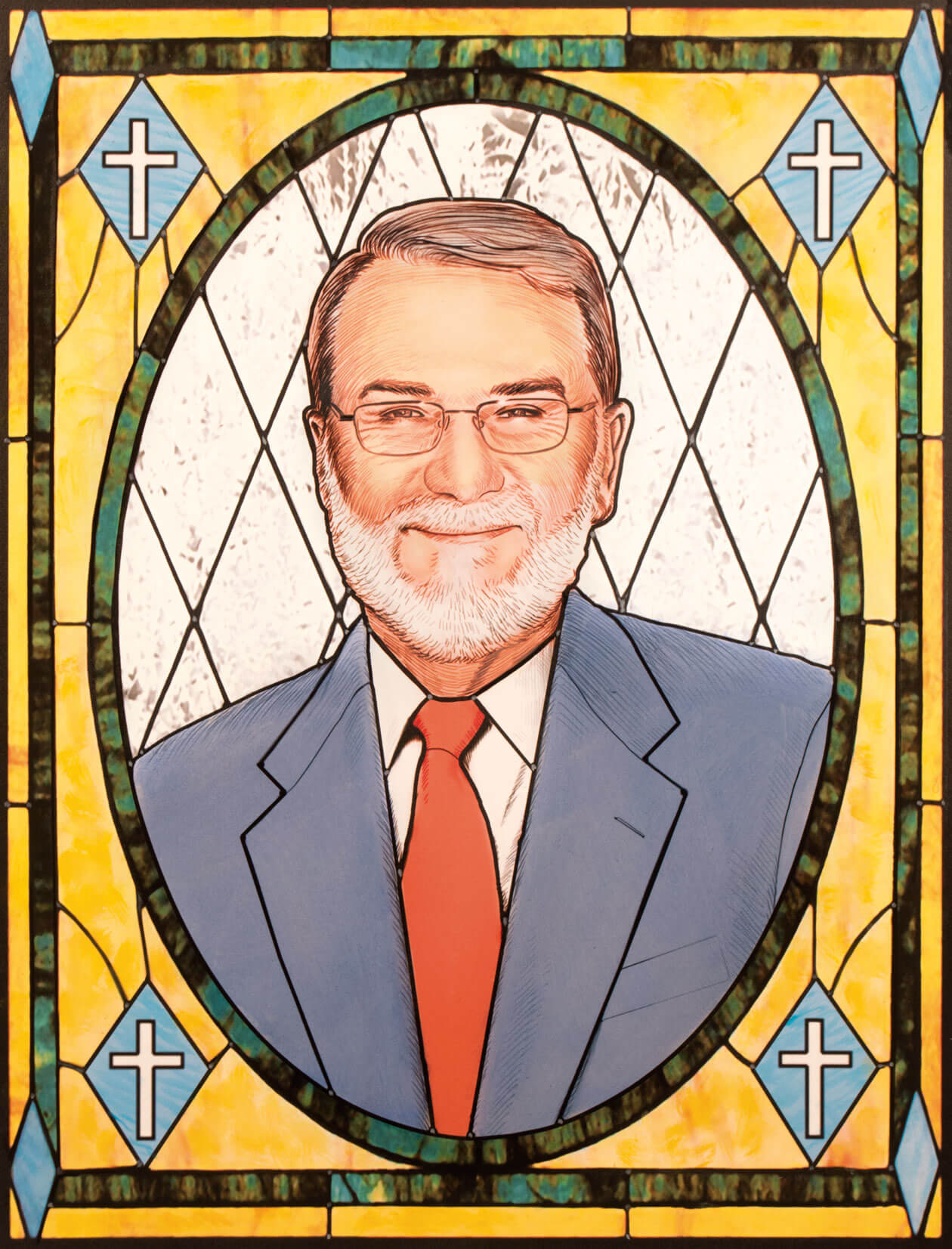

That’s what the Reverend Orville James is afraid of. On the wall of his study at Wellington Square United Church in Burlington, Ontario, is a photo that was taken three years ago. It shows James (now sixty-two), his two brothers, his father (now deceased), and his daughter—all standing proudly draped in their ministerial vestments. On a late Friday afternoon at the church, two dozen volunteers are hurriedly preparing the gymnasium for a weekly supper, which is provided by community partners to 250 people who come from all over the region. James leads me through this commotion to the silence of the church sanctuary, where, along with the standard pulpit and choir loft, there’s a drum set waiting for Sunday’s 9 a.m. service. David Wilson may describe the church as a “black hole” for young people, but here teenagers and young families show up for a bit of Christian rock ’n’ roll. James regularly sees three times as many as people as at the 11 a.m. service, the one he describes as “traditional”—despite the presence of a big-screen TV donated by a ninety-two-year-old parishioner who could no longer read the hymn books’ small print.

Wellington Square went through its own version of collapse. From the mid-’80s to the mid-’90s, it lost more than half of its 1,850 members. James, who arrived as minister in 1996, says membership is now holding fast at around 700. It is an activist organization that provides services well beyond the local community, sponsoring an orphanage in Sierra Leone and building houses in an impoverished Mexican village. Asked about the United Church’s flagging membership numbers, James spins the story. It’s about recruiting, he says—what is known in church jargon as evangelizing. “The only number that counts,” he says, “is 7.5 million,” meaning the nearly 25 percent of Canadians who have no religion. “I’m not talking about stealing Muslims or trashing the Buddha; God is calling us to serve those with no religious affiliation or spiritual connection at all, living lives of secular materialism that aren’t fun anymore and that lead to a wall of despair.” James’s reputation within the church is that of an evangelical, and he’s not about to apologize for it. “I say, God loves us. Christ is alive and risen. We need to tell others.” In 2012, he was nominated as a candidate for moderator of the church, but lost. He has no plans to try for moderator again, but he keeps pushing the United Church not to give up its roots: “There have been exchanges where I express frustration. There is a clear recognition that we have to do something. I’m not an optimist for the United Church of Canada, but I’m an optimist for Jesus’s church. Local community churches will blossom, while organized institutional religion will go through a purging and, maybe, a retrofit.”

Despite the enthusiastic God-fearingness of ministers such as Orville James, loss of traditional religious faith seems to be an occupational hazard for United Church clergy. In 2011, the Observer published a survey asking readers whether they believed in God. Three-quarters of respondents said yes, but 23 percent of laypeople and 24 percent of ministers said, “Depends what you mean by ‘God.’” Most doubters within the clergy remain anonymous, but occasionally a few go public. Five years after retiring from one of the church’s biggest congregations, Metropolitan United, in London, Ontario, minister Bob Ripley revealed his atheism through a 2014 London Free Press column, in which he declared that he no longer believed in God, the Bible, or the doctrines of Christianity, and asserted, like Vosper, that “religion, all religion, is man-made.” Ripley was subsequently asked to resign from the church’s order of ministry, which he did. Ken Gallinger, former minister of Lawrence Park Community Church and ethics columnist for the Toronto Star, asked in 2012 that his name be removed from the church’s ministerial lists. He, too, had fallen away from the faith.

These cases differ from Vosper’s. A sense of loss pervaded Ripley’s and Gallinger’s public declarations; it was clear that they’d contended with the possibility of having wasted years of their time and talent. Vosper’s had none of that. She views her lack of belief in the supernatural as a positive; her mission is to help her church morph into a spiritual community that doesn’t need God to give it meaning.

That’s the sort of thing that Peter Wyatt finds disturbing. Though he has never squared off with Vosper in formal debate, Wyatt—formerly principal of United Church–affiliated Emmanuel College at the University of Toronto—represents the antithesis of everything she preaches. And he firmly believes that she and those clergy who share her views are a detriment to the church. “Doubts are fair enough,” he says, “but the pulpit is not the place to work those out.” He concedes that Vosper does give a voice to people “who are struggling with faith and no longer want to feel related to a transcendent god.” But, he says, her tack is wrong. “I see progressive theology as it’s defined in Canada as dismantling the faith. I don’t think that a godless religion can really be convincing to anyone. There’s no thou, and I don’t know how religion can flourish without the thou.”

Wyatt jokingly describes himself as an “out-of-the-closet Wesleyan”—meaning his religious beliefs are rooted in the eighteenth-century English Methodism that was a founding pillar of the United Church. He acknowledges the difficulties that the church set for itself when it opted to go easy on doctrinal matters in favour of a peaceful union of denominations. “One of the running themes of the United Church is that we’re very pragmatic,” Wyatt says. “It’s not that we don’t have doctrine, but we’re always trying to make our doctrinal teaching catch up to what we’ve already done.” The vaunted liberal theology of which the church has long been the vanguard, he points out, has generally resisted imposing an orthodoxy on believers’ freedom of conscience. But that was never supposed to mean abandoning the core convictions of the Christian faith. “We have official teaching that is clearly Christian, clearly Trinitarian. Jesus Christ is central to our faith; the Bible is respected as a normative authority.” Take that away, Wyatt says, and we’re left with “the secular humanist society.”

Vosper pushes back with her own version of pragmatism. “How do we who have been nurtured within liberal mainline Protestantism, who have this set of values, transmit them to a new generation?” she asks. Her fight to stay inside the church continues. She’s hired lawyer Julian Falconer and appealed the right of church courts to call her to account. The reason she wants to stay is at once simple and profound: “I am a product of the United Church of Canada,” she says. And she wants to be a part of the battle for the soul and the future of the church—or whatever comes after it. “We need, if not the existing institutions, then some recognized, validated way to engage community around those values so we can transmit them beyond our own selves,” she argues. “I think the United Church has the opportunity to do that.”

Whether Vosper’s way is the future is impossible to tell, at least for the moment. The United Church faces daunting challenges, and for traditionalists such as Wyatt and James, Vosper and her views are just one of them. What is clear is that Canada’s so-called national church is at a crossroads. The question is which route it will take, and whether it will run or falter.

This appeared in the May 2016 issue.