I’m huddled in a forested bend of the Rideau River, southeast of downtown Ottawa, totally spooked. It’s suppertime and near dark in mid-February. Cars careen along Riverside Drive, but all I hear are thousands of shrieking crows, crowding the bare branches like burned apples. The snow is knee deep inside this communal roost. I close my eyes, and after a few minutes the caw-caw-phony modulates into a kind of radio static, within which I swear I can hear human whispers.

I’m shivering under a toque moist with bird droppings; maybe it’s time to go. I whisper my goodbyes to the inky convention and step-sink my way through the crusty snow to the road, turning around for a final look to see the entire roost above me in flight, a giant, rippling houndstooth blanket drifting toward the Ottawa Hospital, General Campus, where, each winter since 2005, the crows have sought overnight comfort and safety in the industrial warmth and light. Maybe, jokes Carleton University biology lecturer Michael Runtz, they sense weak and dying humans there.

American crows, as these ones are known, used to roost farther south, but urbanization and a warming climate have made Canada more hospitable in winter. In recent decades, they have chosen suburbs over forests, and as a result their life expectancy has doubled. Like us, they enjoy big yards and leafy hedges, fast food and weekly garbage pickup. And, as it turns out, that’s not all we share.

Striking Resemblance

In Nazi Germany, an artist’s talents prove fatal

Luc Melanson

German portraitist Emil Stumpp considered journalistic photography inferior to illustration, because it produced “laughably incidental moments.” As an illustrator for the popular newspaper General-Anzeiger für Dortmund, he provided what critics have called an “incomparably clearer and more graspable depiction” of reality. Stumpp’s renowned portraits of such German intellectuals as Albert Einstein and Magnus Hirschfeld have been lauded for their precision and their vibrant “processuality.” In 1933, his drawing of Adolf Hitler appeared on General-Anzeiger’s front page, to mark the newly elected chancellor’s birthday. The uncanny illustration portrayed the Führer with a stern, if not angry, expression. Hitler hated it. The government swiftly shut down the newspaper and prohibited Stumpp from working in Germany. He remained critical of the Nazi regime, and in 1940 he was arrested for treasonous acts. He died in prison the following year.

—Barry Chong

I admit it’s creepy standing in a murder of crows. I blame Alfred Hitchcock for that—the word “murder” doesn’t help either—but there have been other culprits. Mark Twain, in 1897, imagined crows as multifarious scoundrels, including a low comedian, a swindler, a professional hypocrite, a trading politician, a conspirator, a lecturer, and, my favourite, a dissolute priest. It’s easy to pin malevolence on corvids, the family that encompasses crows, ravens, jays, rooks, magpies, and nutcrackers, but, as Twain illustrates, the same holds true for Homo sapiens.

Crows are unpopular, with good reason. They are obnoxious bird bullies with shrill voices, scattering trash and gumming up eavestroughs with their detritus. But perhaps our scorn springs from a deeper source. McGill University biologist Louis Lefebvre has suggested that we dislike them because they remind us of our unsavoury selves: opportunistic and invasive. Plus we would both eat anything to survive. That last attribute may have been the turning point between our ancient reverence for corvids—among Native American and early Asian peoples, for example—and our modern aversion to them. Watching ebony flocks descend on the plague-ridden streets and bloody battlefields of medieval Europe to pick at rotting corpses must have been gruesome, says John Marzluff, a University of Washington wildlife scientist and long-time corvid researcher. Hence “eating crow”; who could eat one after seeing that? Of course, they were just doing what they’ve always done: scavenge for leftovers.

Crows and people have been interacting for millennia: the paleolithic caves of Lascaux, France, contain a painting of a man with a crowlike head. As humans learned to hunt and fish, crows followed us and waited for the scraps. When we became agrarian, they gleaned our corn and other crops. We hung their corpses on fence posts and built scarecrows to frighten them away. As we destroyed their original habitats to build cities, they discovered a smorgasbord of food and fewer predators in their new environment—what Marzluff calls “an Eden for crows.” They ate nestlings, plucked bugs from ornamental shrubbery, and gouged greasy garbage bags. They learned to eat french fries and cheese puffs, and to drop nuts onto busy roads to be cracked by car tires. We engineered better Dumpsters and trash cans, put fake owls on rooftops (unfortunately, they know the difference), and added “caw-caw” to the canon of sounds filmmakers use to foreshadow doom.

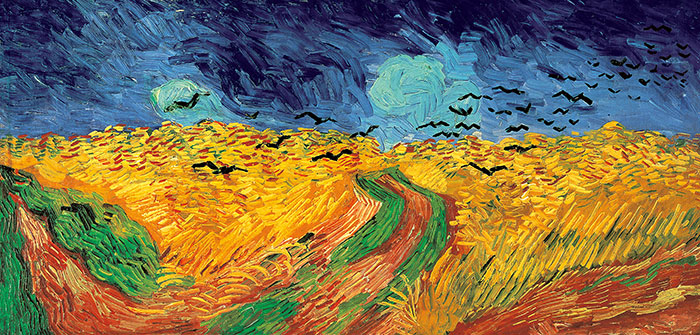

Crows have insinuated themselves into our literature, art, language, and music. (I’ll need a crowbar to remove this Counting Crows disc so I can watch The Crow.) Vincent Van Gogh painted the exquisite Wheatfield with Crows. William Shakespeare employed the sooty bird to connote foreboding. Both ravens and crows figure prominently in the folklores of cultures as disparate as Haida, Jewish, and Celtic. The crow is creator and destroyer, hero and villain.

It was Marzluff who connected the dots: in our braided quest for food and shelter, humans and crows have influenced each other in a process he recently dubbed “cultural co-evolution,” a unique interspecies one-upmanship that will likely accelerate as cities, and urban crow populations, expand. “To know the crow is to know yourself,” he told me, and nowhere is that more poignant than with our trash. Every day this summer, after scores of snacking human families vacated a nearby wading pool, flocks of crow custodians appeared like clockwork, vacuuming up the fishie crackers and fruit leather. “Crows’ ability to exploit the by-products of our lifestyle means we are responsible for their success,” Marzluff says. “That’s what they’re mirroring back to us: that we’re sloppy.”

But their success is not entirely our doing. Crows are a highly evolved, family-oriented, social species, able to adapt quickly, solve myriad problems, use complex tools, and remember for years the faces of enemies and allies. They are fellow survivors, adapting to, and alongside, us. Chimpanzees and dolphins are smart and social, too, but how often do we interact with them? Corvids live on every continent except Antarctica, but they especially love it here in Alta Vista, my leafy ’50s Ottawa suburb. It’s a swell place to raise a family, winged or otherwise.

My neighbour, local writer and reluctant bureaucrat Christian McPherson, wrote a poem about crows for his latest collection, comparing their daily winter migration to his daily egress from the cubicle: “I love them like my own children, who are the only reason why I’m still walking to and from work. Do the crows fly out of love or necessity or is it the same thing? ” We slog through nine-to-five days, shrugging off indignity and monotony en route to a paycheque. We exploit all available resources, including other species. That’s not love or necessity. It’s nature.

This appeared in the November 2011 issue.