At their core, reading and writing are ethical pursuits. They’re reconnaissance missions, Trek-ish endeavours to explore strange new worlds and seek out new life and new civilizations. George Eliot, the quintessential literary ethicist, summed it up like this: “A picture of human life such as a great artist can give, surprises even the trivial and the selfish into that attention to what is apart from themselves.… Art is the nearest thing to life; it is a mode of amplifying experience and extending our contact with our fellow-men beyond the bounds of our personal lot.”

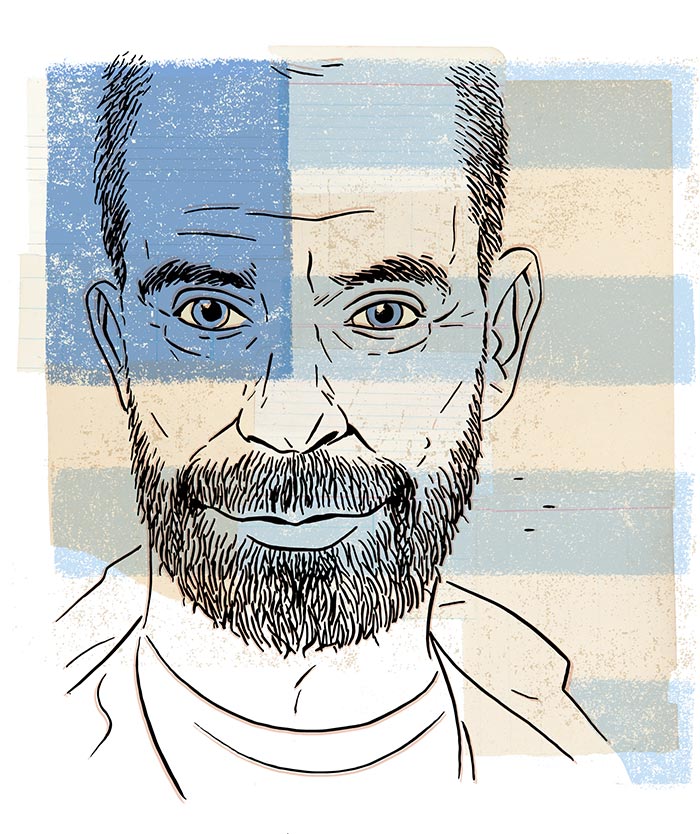

Few twenty-first-century writers have achieved this mode with the grace and compassion of David Rakoff, the Montreal-born, Toronto-raised, New York–naturalized scribe known for his wry, woeful essays. He published three collections before his death; his final and finest, Half Empty, won the Thurber Prize for American Humor in 2011.

He came of literary age in the 2000s, alongside his friend and fellow radio geek, David Sedaris. To a certain extent, Rakoff was Sedaris’s bizarro-world counterpart. Both were gay funnymen named David who regularly appeared on the public radio program This American Life, and both spoke with slight, elegant lisps. However, while Sedaris’s folksy farces exploded into the mainstream, Rakoff’s exquisite tragicomedies attracted a smaller but equally zealous fan base. He died of cancer last summer at forty-seven, after a protracted cycle of illness, surgery, and radiation. In eulogies and tributes, friends and admirers praised his wit, insight, and facility with language. His moral vocation received less ink.

To understand Rakoff’s ethics, you must first understand his anxiety, a condition that underlined everything he wrote, and could easily have put him at a disadvantage. After all, optimism, liberalism, and self-actualization form the core of American values; anxiety is seen as a character flaw. For Rakoff, though, anxiety and its attendant pessimism were just as valid as optimism. “Defensive pessimism is about sweating the small stuff, being prepared for contingencies like some neurotic Jewish Boy Scout, and in doing so, not letting oneself be crippled by fear,” he wrote in Half Empty.

He was not, however, a nihilist. His melancholia was vaguely romantic, as though some scientist had swirled Heathcliff’s DNA in a petri dish with Tevye the dairyman’s. Rakoff’s essays were elegantly drawn and ordered, tinged with empathy, courage, and a shred of hope.

Moreover, they were adventure stories. An occasional actor, he undertook bit parts in As the World Turns, and The First Wives Club (where he was fired and replaced with Bronson Pinchot). He donned hiking boots—“large, ungainly potato-like things [that] cut into my feet and [drew] blood as if they were lined with cheese graters”—to climb a mountain in New Hampshire. He even enrolled in a three-day Tibetan Buddhist seminar led by action star Steven Seagal.

All writers, and by extension all readers, have a responsibility to use literature as a way to engage with the world outside their own bubble. That onus can translate into blissful escapism or an unnerving unknown. Either way, literature acts as a bridge between the self and the other. Rakoff was the ultimate outsider, the gay Jewish Canadian alien living in New York, the introvert in a world of brash self-promotion. By venturing into the abyss—playing the part of the guy who climbed mountains, went to survivalist conventions, acted on soap operas—he gained access to a society that had eluded and excluded him. For his readers, he was an undercover proxy into that world.

Rakoff believed identities are shaped by the self we present to the world, the deeds we perform, and how we interact with others. His last book, a novel in rhyming couplets called Love, Dishonor, Marry, Die, Cherish, Perish, was published posthumously in July, just shy of the first anniversary of his death. Love, his first novel, funnels his idiosyncratic world view into fiction. Though just over 100 pages, it is epic in scope, a series of interconnected vignettes that traipse from a turn-of-the-century Chicago tenement, to San Francisco at the onset of the AIDS epidemic, to modern-day Manhattan.

Love is an unpolished work. Some of the rhymes are brilliant: “I won’t wish them divorce, that they wither and sicken / Or tonight that they choke on their salmon (or chicken),” a man muses before toasting at his ex’s wedding. But for every good line, there is another that halts and stutters on the tongue. (One particular stumbler: “At school, Margaret learned basic reading and sums—/ But mostly developed a hatred of nuns, / Who seemed to delight in a disciplinary / Code just as ruthless as ’twas arbitrary.”) The plots are occasionally murky and confused, ideas not fully formed, and the story gets lost in his ambitious approach. Perhaps Rakoff, whose earlier prose was always carefully considered and precise, died before he could work out the kinks.

Yet the novel is somehow perfect: fragile and funny and bleak and hopeful, its moral that fable about a scorpion who rides across the river on the back of a tortoise, only to sting his helper and kill them both: “I think what it means is that central to living / A life that is good is a life that’s forgiving. / We’re creatures of contact, regardless of whether / To kiss or to wound, we still must come together.”

Those lines, perhaps more than anything he ever wrote, distill Rakoff’s world view—one that recognizes the universe as a random, tragic, fear-driven assemblage of atoms, but insists that while we are here we might as well attempt to understand one another.

It is impossible to read Love without thinking of Rakoff’s Judaism. Secular though he was, the intersection of action and ethics is as Jewish as it gets. Unlike Christianity, which focuses on spirituality and the afterlife, Judaism is an identity that comes into being through action. It is as much a lifestyle as it is a religion, governed by performative rituals: prayer, dress, diet, and mitzvoth—commandments, or religious calls to action.

Toward the end of the novel, we encounter Shulamit, née Susan, a middle-aged New York divorcee who has made a religious journey to Israel: “She’d needed to be here. No con game, no trick. / Her life was a cancer, her spirit was sick.” (She also re-dubs her WASP-named kids, from Chip and Schuyler to Duvid and Naftali.) Shulamit’s voyage is a personal pilgrimage, but it is also the fulfillment of a mitzvah.

Rakoff cheekily exploits that legacy in the novel. Shulamit’s pilgrimage is the ultimate Jewish mitzvah, but it’s the other acts that shape the novel’s moral character. The first story, for example, about a twelve-year-old slaughterhouse worker who escapes Chicago by train after her stepfather rapes her, concludes with the girl being solaced and sung to sleep by a kindly Jewish immigrant. Decades later, we encounter the Jewish man’s son, Clifford, a shy, closeted gay teen with a gift for art, who enlivens his cousin’s faltering self-esteem by taking her photograph. Each of these is a secular mitzvah—a riff on the religious commandment that encourages kindness, not piety.

Read literally, Love is an intimate, O. Henry–esque fable about the minuscule ripple effects of our actions. On a larger scale, it is a revisionist look at American history, a subversive ode to the culture and the country in which Rakoff spent the better part of his life.

Not to belabour the Semitic angle, but consider the other Jewish writers and artists who have wrestled their way into the American narrative by circuitous means. There is Joe Shuster, the Jewish Canadian co-creator of Superman, the ultimate alien outsider who becomes the quintessential undercover American hero. Or E.L. Doctorow, whose epic novel Ragtime explores the American dream from the perspective of Jewish immigrants like Emma Goldman and Harry Houdini (along with Booker T. Washington, the Jim Crow–era African American educator and civil rights leader). Or Irving Berlin, the Russian-born Jewish songwriter, who found a place in the WASP world by writing the yuletide juggernaut “White Christmas.”

With Love, Rakoff joins this vaunted crew, even inserting himself into his mono-myth: Clifford is the author’s double. After the character’s first appearance as a teenager, we meet him again as an adult in ’70s San Francisco, revelling in the Castro district’s gay counterculture. Some years later, he discovers a “plum-colored smudge, a sloe slowly blooming”—Kaposi’s sarcoma, a sign of HIV.

Clifford’s perseverance while his body slowly erodes echoes Rakoff’s own illness, a wrenching ordeal that reduced him to a ghostly carapace. Nonetheless, right up until he died, he continued performing, writing, acting—all of the things that confirmed his existence. Through Clifford, he articulates that feverish need to stay alive: “A new, fierce attachment to all of this world / Now pierced him, it stabbed like a deity hurled.”

In May 2012, after a surgery on his collarbone severed all of the nerve endings in his left arm, he appeared on a live taping of This American Life. He strode onstage, bum arm in pocket, “hanging from my side heavy and insensate as a bag of oranges.”

He described how, with death soon upon him, he no longer felt any need to give up his vices and be his best self: “I’m done with all that. I’m done with so many things. Like dancing. I’ve no idea if I can do it anymore. I’ve been, frankly, too frightened and too embarrassed to try it.” Overcome with emotion, he stepped away from the microphone and performed a nimble one-armed dance, all graceful spins, sweeping strokes, and fancy footwork. It was the culmination of a life propelled by action—the ultimate Rakoffian mitzvah.

This appeared in the September 2013 issue.