Like most outspoken government critics in Colombia, Carlos Julio Pérez is no stranger to death threats. He has fielded several during his tenure as president of the Antioquian chapter of Colombia’s largest union, the Central Workers’ Unit, a post whose high profile earns him the small irony of a government-sponsored security detail. When I visited the quiet residential street in Medellin’s centro where Pérez lives last August, two officers drove past periodically to keep an eye on things.

“It’s harder to form a union today than ever before,” Pérez said. “In theory it’s no problem, the laws are all in place, but in practice you get fired or intimidated or hurt the moment you try to organize. Paramilitaries often work with local and international companies to threaten unions—the pamphlet arrives, the phone call comes, and you know what’s next if you don’t put your head down. In the past two years I’ve tried to help seven different unions get started, and all of them failed because of threats and murders. And this is in Medellin, where we are surrounded by authority.” I asked him if he thought the authorities were complicit in Colombia’s anti-union violence, and he laughed, then told me about Guillermo Valencia Cossio, Medellin’s former chief public prosecutor, who had recently been indicted for colluding with paramilitaries and drug lords. Cossio wound up in jail, but Pérez insisted this was exceptional. “If you go to Segovia, you’ll see the head of the local paramilitary unit drinking whisky with the local army chief.”

Pérez doubted the free trade agreement Colombia had recently signed with Canada would change much; its main impact, he felt, would be to pressure the United States to finalize its own deal with Colombia. “And if that happens,” he said, “it will only promote more displacement and narcotrafficking in Colombia, because the small farmers are going to lose their farms, and small businesses and industry will be ruined. This will continue to be a country that relies on foreign companies to export its own raw materials, rather than one that invests in its own industrialization.”

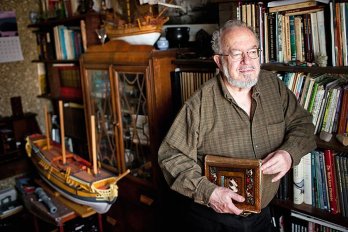

Few have studied anti-union violence more closely than José Luciano Sanín Vásquez, founding director of the National School of Unions, a Medellin-based labour NGO. Sanín, a calmly alert chain smoker eight months clear of his most recent death threat, smiled when I asked him if things weren’t getting better for Colombia’s unions. According to his own organization’s research, the number of murdered union leaders has fallen over the past decade from about 200 a year to less than fifty.

“The best our government can say is, ‘We don’t kill as many unionists as we used to,’” Sanín replied. “We’re talking about a structure that has been kept in place; the numbers rise and fall, but the killing of union leaders continues. Every day there is an act of violence against a union leader. These are almost never investigated.” The Medellin schoolteachers’ union alone had reported seventy-seven death threats in the previous two years, none of which was resolved.

When I asked Sanín about the labour and human rights clauses added to the free trade agreement to address such concerns—both countries are committed to annual impact assessments of the FTA’s effect on human rights—he dismissed them as “a rhetorical exercise with no consequence.

“At least they’ve recognized that free trade is tied to human rights,” he said. “But there’s no mechanism to make either parliament react should bad news come up; even worse, there’s no third party in any of this to guarantee impartiality. We’re trusting the very people who have raised our suspicions to investigate themselves.”

This appeared in the May 2011 issue.