In order to reach the permanent display of Northwest Coast Indian artifacts at the American Museum of Natural History in New York from West 81st Street, you have to descend a stairway and walk through a newly renovated, glass-enclosed gift shop stocked with kitschy facsimiles of the tools, jewellery, clothing, and headdresses of the peoples represented in the museum’s vast collection. From there you enter the damp, poorly lit bowels of the nineteenth-century museum. There, bison set behind thick panes of glass gallop in front of painted sunsets; mangy grizzly bears rear back on their hind legs, long claws chipped and brittle, dark glass eyes off-kilter. And in the next room, in beautiful old wooden cabinets, is what was at one time regarded as just another instance of the flora and fauna of North America: crudely sculpted, faceless Tlingit tribesmen in fringed robes and beaver-fur hats; dancing Nootka shamans in heavy bear costumes; and brightly painted Kwakiutl masks. What is not on exhibit, but is still part of the collection, are the thousands of skulls and skeletons of native Americans that were exhumed from graves by archeologists during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and even boiled down from fresh corpses strewn on battlefields.

Vancouver artist Brian Jungen stands in the doorway of a room at the New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York near the installation of his Prototypes for New Understanding, a series of twenty-three masks cunningly fashioned from Nike Air Jordan sneakers and human hair that bear a striking resemblance to the masks of Northwest Coast Indians. With his stocky build, broad face, and deep, dark eyes, Jungen casts a humble yet formidable presence.

It is just a week after an important mid-career survey of the thirty-fiveyear- old artist’s work opened at the New Museum (the show will subsequently travel to the Vancouver Art Gallery and the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal). But it is merely the latest step in Jungen’s ascent; over the past three years, the artist has had solo exhibitions in Montreal, Vancouver, Seattle, San Francisco, New York, and Vienna. It’s a long way from the interior of British Columbia, where Jungen, the child of a Swiss father and an aboriginal mother, was raised on a family farm on traditional Dane-zaa lands, before moving to Vancouver in 1988 to study at the Emily Carr College of Art and Design. Still, despite the exposure, the reserved, intense Jungen—hands in the pockets of his jeans, eyes fixed on the floor—is clearly ill at ease speaking in public. When asked about the relationship between his work and the art of his native ancestors, Jungen looks annoyed and impatient. “I was sort of pressured to make work about my identity, but then a lot of my exposure to my ancestry is through museums,” he says. “And the objects and artifacts in museums are not actually ceremonial.”

One of the most striking things about Prototypes for New Understanding, before the rich irony and cutting humour become apparent, is how beautiful and finely crafted the fierce, confrontational masks are. Clearly that is part of the reason they were such a catalyst for Jungen’s career. In “Prototype for New Understanding #4” (1998), for instance, the artist has unstitched the padded white leather tops of the shoes and splayed them out into a face, the black sides stretched and stuffed to form a pair of goofy ears, and the plush red interior pulled out to form a thick, curled tongue. Long strands of coarse black human hair hang from the back of the mask; in its otherwise empty white eyes is the Air Jordan logo, Michael Jordan leaping mid-air for a slam dunk.

“Prototype #9” (1999) has a grotesque, even menacing bent snout and lurid red lips; in “Prototype #11” (2002), buckled red leather bands strap shoes around a crinkled mouth hole to look like outstretched wings from which hair cascades; and the hooked beak in “Prototype #13” (2003) gives the appearance of a prehistoric bird, with a long shiny tail of hair attached to the back. Many of the sculptures in Prototypes for New Understanding resemble the distorted, shapeshifting animal forms—now demonic, now obscene and comic—common in Northwest Coast masks. But Jungen considers this series to be at least partly an exploration of material and form, and works such as “Prototype for New Understanding #20” (2004), a mandala-like wheel of shoes, as well as the closely related wall relief Variant I (2002), are almost wholly abstract. “My work is not about my personal relationship to these [native] traditions,” Jungen told me, “but about the interface of traditions with wider contemporary culture. I am interested in the role of native art in culture rather than in an interpretation of that culture.”

In a 1999 exhibition of the Prototypes in Vancouver, Jungen also included mural-sized wall paintings based on sketches he solicited from passersby, who had been asked to draw what they thought of as “native art.” Rendered in cheerful colours, the works reflect crude stereotypes of both aboriginal people and the range of aboriginal art: there are eagle heads, Indian braves in war paint wearing feathered headbands, teepees, totem poles, and frolicking whales. These drawings are fantasies about what historian Daniel Francis calls the “Imaginary Indian,” a romantic figure created since the middle of the nineteenth century by the depictions of First Nations people and culture by writers, painters, anthropologists, filmmakers, politicians, and others. Prototypes addresses a similar issue, but from a different and more complicated angle.

Northwest Coast masks have been fetishized and obsessively collected as shining instances of authentic aboriginal art. Jungen, on the other hand, has taken a popular line of a brand that has itself become a collector’s item and transformed it into one-of-a-kind works of “native art” that might in turn be mass-produced. “Before products are outsourced for production,” Jungen told me, “a design team creates several prototypes of which one is selected. I liked this idea of reversing it by using the mass-produced object to create a singular handmade prototype. I thought the Jordan trainers were a perfect icon to illustrate the idea of a global product reworked by the local.” Yet Jungen’s masks also suggest a different kind of prototype—one for a native art, and a native identity, that are not paralyzed by the past, that have the impurity and flexibility to move into the future.

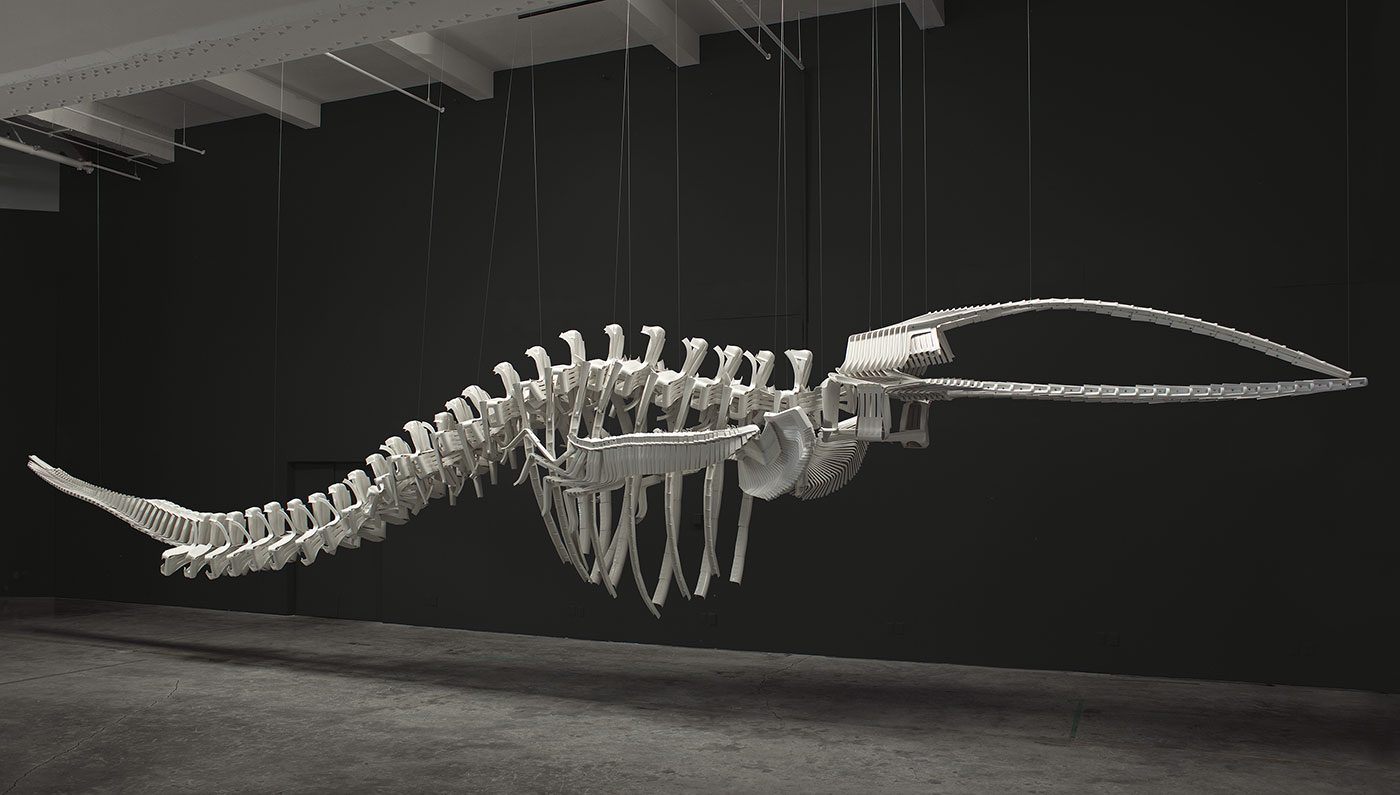

For another series of sculptural works, which includes Shapeshifter (2000), Cetology (2002), and Vienna (2003), Jungen crafted what look like huge whale skeletons made out of white plastic lawn chairs. Like Prototypes, Jungen’s skeletons do not initially appear to be constructed out of familiar, mass-produced material, a fact that comes as a revelation to most viewers, complicating an otherwise pristine illusion. In Shapeshifter, the tail has a long, slow undulation, but the central portion of the body is compacted and the head sharp, a ribbed cartilage at the top like a fin. Vienna, on the other hand, has an intricate body composed of curved parts that seem captured in a whipping, forward motion, its head long, elegant, and open.

Jungen’s refined formalism and meticulous craftsmanship are counterbalanced by the materials he employs and the histories his images evoke. The whale skeletons are not meant to be anatomically correct, but they are modelled after skeletons typically housed in natural-history museums. Indeed, the giant plastic sculptures are suspended from the ceiling and bathed in clinical white light that self-consciously evokes the style of presentation in museums, and they are closely related to the concerns of Prototypes. After all, whalebones are the remnants of a species driven to the edge of extinction by white North America’s voracious appetite for the fuel oil extracted from whales, and they are also part of the collections of museums whose storage vaults are stocked with the artifacts and bones of aboriginal peoples.

In these works, Jungen is interested in the way the skeletons evoke the stories and myths of the Northwest Coast tribes. In addition, the petroleum used in the manufacture of the plastic chairs nods not just to the whaling industry but more generally to the expansion of European civilization on the Western frontier that irreversibly disrupted the lives of First Nations peoples. These are among Jungen’s most lyrical works. Suspended from barely visible string, the white of the plastic chairs is cool and ghostly, and a sculpture like Cetology looks fragile, held together by a delicate balance. It is a triumph that something eerie and beautiful can be salvaged out of material as mundane as plastic chairs.

Not all of Jungen’s work is overtly about the stereotypes with which First Nations peoples have typically been cast or about questions of identity in a global society, but these issues have a way of creeping into his work. This may be because Jungen’s art subtly raises the question—without answering it—of the possibility of a regional culture and identity that moves beyond nostalgia in a world where a kid can grow up on remote Dane-zaa lands and learn less about First Nations culture than about the television programs and pop music and hip-hop fashions worshipped by kids in Toronto. Jungen has often insisted that the work he makes out of Air Jordan trainers is not inspired by a passion for the player or for basketball but rather by the branding and celebrity-endorsement issues that arise from professional sports.

The somewhat cagey Jungen now admits there is probably more to it. “I only considered this idea of ceremony a few years ago,” he said. “It occurred to me that I was making facsimiles of one kind of ceremonial garment out of another and that the role of sport in culture in a way fulfills a kinship ritual that ceremonial competitions once did in non-western societies.”

In a society where religious ceremony no longer creates a sense of collective identity, sport is the secular ritual that provides fantasies of excellence and moments of transcendence. For Court, which debuted in 2004 at Triple Candie gallery in Harlem, New York, Jungen built a basketball court to scale out of 224 wooden tabletops that had been used in sweatshops, leaving open the rectangular holes and notches where the industrial sewing machines would normally be set. The three-point arc is carefully painted in; there are hoops suspended at either end. The laminated wood of a basketball court, waxed and polished to a mirror shine, has a sleek, seamless elegance, but Jungen’s court is thick and even brutal, and the ironies it embodies are equally blunt. The sewing machines that would have been screwed into the tabletops could easily have been rattling in front of workers in the crowded sweatshops of China, cranking out the beautiful and heraldic white, black, and red Air Jordans that would eventually be on the feet of nba stars or those of native kids fantasizing about those nba stars.

Jungen’s court is one that the viewer figuratively trips over. It is more than simply a statement about the brands and endorsements of big-money sports and the hard economic realities that underlie them; its metaphors are far more ambiguous and suggestive than that. Perhaps basketball courts stand in for the ceremonial spaces—religious, political, social—that have traditionally served to bind a people’s identity. Perhaps what Jungen’s fractured, makeshift court implies is the great extent to which such spaces have become compromised.

Brian Jungen’s art inevitably has an ambivalent relationship with museums, even those devoted to contemporary art, where curators are sensitive to the suspicion with which artists often approach institutions. A lot of Jungen’s early work is fuelled by an interest in the institutional presentation of First Nations culture as an appropriate object of scrutiny for scientists rather than students of human history. David Hurst Thomas’s seminal history of anthropology and archeology, Skull Wars, was premised on the idea that native culture was essentially extinct. Art works such as Shapeshifter and Cetology were in part inspired by visits to Vancouver’s aquarium, a different kind of museum, its thick glass windows providing an underwater view of the resident killer whale. Jungen commented, “I wanted to reference the aquarium and the captivity of the animals,” and that seems more apt: works of art in museums often feel as though they are being held captive, in a kind of solitary confinement, unable to engage with the world unfolding around them.

In recent years, Jungen has become increasingly oriented toward temporary works set in less institutional environments—what he likes to call “structures for habitation.” His interest in architecture, in the aesthetics and politics of the spaces in which we live, is by no means new. Isolated Depiction of the Passage of Time (2001) is modelled after a hollowed-out stack of blue lunch trays that were used in a 1980 prison escape from the Millhaven Institution and which are now part of the collection of the Correctional Service of Canada Museum in Kingston, Ontario. In Jungen’s piece, each of the approximately 1,200 trays represents an aboriginal male incarcerated in a Canadian prison, the different colours correspond to the length of sentences meted out, and the sounds one hears represent the televisions provided in the windowless cells. For Little Habitat I (2003) and Little Habitat II (2004), Jungen meticulously cut up Air Jordan boxes and assembled them into compact geodesic domes. Both Isolated Depiction of the Passage of Time and the Habitat works are about alienation and failure—of architecture used to isolate and repress, of a mode of high-modernist formalism that Jungen is clearly drawn to but that is disconnected from the character of living communities.

Several of Jungen’s recent projects, on the other hand, propose a more symbiotic relationship between “structures of habitation” and the world that surrounds them. Habitat 04—Cité radieuse des chats/Cats Radiant City (2004), first shown at the old Darling Foundry in Montreal,consisted of stacked plywood units covered with carpet that served as temporary housing for some of the city’s many stray cats. Jungen and staff at the Darling Foundry worked with the local humane society in an effort to arrange for the adoption of the cats.

Echoing the title of Le Corbusier’s never-realized Radiant City, and alluding to Moshe Safdie’s Habitat 67 housing project in Montreal, Habitat 04 introduces the flux and indeterminacy of life into austere modernist forms. For Inside Today’s Home (2005), Jungen constructed an elaborate suspended birdhouse for domesticated finches out of ikea periodical- file boxes and shelving brackets. The exhibit was viewed from the outside, through peepholes in a plywood wall or on closed-circuit television.

Compared with Court, Habitat 04 and Inside Today’s Home are optimistic works. They suggest that we need to stop thinking of the divide between nature and culture as sharp and unequivocal, that we need to give up the idea that history offers us identities and ways of living that have stable boundaries. Perhaps what it means to be part of a live culture, rather than terminally relegated to the storage facilities of museums of natural history and anthropology, is to be part of something that is unstable, ephemeral, and continuously transforming.

At the end of his talk and walking tour of his exhibition at the New Museum, Jungen glances at Modern Sculpture—blobby floor sculptures made from silver soccer balls filled with lava rocks he created for a group show in Iceland—and moves on to talking stick (2005). Jungen may be drawn to the kinds of site-specific installations that are popular with critics, but he is at heart a sculptor and a consummate craftsman.

Jungen’s creation talking stick is a series of works made from baseball bats carved with what look like the designs found on Northwest Coast totem poles and batons, but are in fact politically charged slogans such as “Unite to Crush” and “Work to Rule.” Like Prototypes for New Understanding, talking stick contains conflicting and irresolvable associations between batons used by Northwest Coast medicine men and sports, between healing and violence, between the finely crafted and the massproduced—between the local and the global.

At one point an earnest-looking woman raises her hand, introducing herself as someone from Vancouver living in New York. She suggests that audiences outside Canada are not likely to understand how controversial Jungen’s use of First Nations culture really is. This is not an altogether naive comment. Jungen’s relationship to First Nations culture is never straightforward, and he always insists upon the impure and the hybrid over the “authentic.” He is not a West Coast native craftsman, but an artist whose work is rooted in European and North American sculpture of the past fifty years. Perhaps his art suggests that the distinction itself is becoming less and less meaningful. “[Some native people] think it’s a cunning way of addressing these issues,” Jungen says, not missing a beat. “They think it’s a funny joke.”